This review is a sister piece to my review of 177. I recommend reading that first.

CW: Sexual assault. The four-letter ‘R-word’ is invoked repeatedly without censoring or obfuscation.

WHEN YOU CATCH A GIRL YOU MUST FIND RIGHT TIMING FOR MAXIMUM RESULT WHICH WILL BE SHOWN ON LOVE METER ACTION OF LOVE MAKING IS BY PUSH BUTTON. BEST TIMING WILL PRODUCE MOST ECSTATIC RESULTS ON FEMALE METER.

Lover Boy is functionally unremarkable, seemingly of as much import as Min Corp.’s Gumbo or Toaplan’s Pipi & Bibi’s. Unlike those games, however, Lover Boy is mired in obscurity, controversy, and a historiography that crumbles under scrutiny.

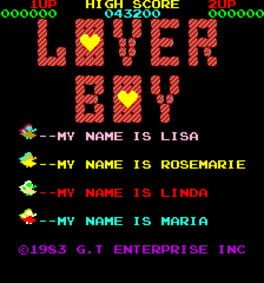

The gameplay is in line with other maze games of the early 1980s. The Lover Boy chases Lisa, Rosemarie, Linda, and Maria through a labyrinth while police officers and dogs track him. There are item pickups for points, and bottles of perfume which incense Lover Boy, boosting his speed dramatically. All the while, a rendition of the nursery rhyme しょうじょうじのたぬきばやし 「 Shoujouji no Tanukibayashi」 plays merrily. Getting near the girls causes them to run away while yelling HELP, touching them starts your digital assault. Like 177, the player tries to get their victim’s pleasure meter to top out before Lover Boy climaxes. Though 177 used directional inputs, Lover Boy simply has you tapping the button at a steady rhythm. Filling the LADY LOVE to the heart at the top has the women elate Oh~. Climaxing before she can has her yelling NO! and escaping, Lover Boy needing to chase her down again.

Though less explicitly stated in Lover Boy as compared to 177, we see the same rape myth being perpetuated, that of rape becoming a consensual sexual act should the victim reach orgasm. Since Lover Boy is an arcade game, designed to munch the yen of the aroused, there is no good ending to speak of here. The cycle continues in perpetuity until Lover Boy is put behind bars for good. This might suggest an inevitability to the rapist being caught and punished accordingly in due time, but the lives system inadvertently paints a picture wherein a sexual criminal is released and allowed to repeat their crimes with minimal repercussion. Lest we forget the harrowing injustice presented in 177’s manual, “even if he was prosecuted then, he would not be charged with a crime.” Capture is thus an inconvenience, nothing more.

In trying to find out more about Lover Boy, I came to find out it was cause for debate in the Deutscher Bundestag a year after its release. On March 26, 1984, parliamentary spokespersons for Die Grünen (The Greens) Marieluise Beck, Petra Kelly, and Otto Schily brought to the attention of the federal government the installation of light-gun games and Lover Boy in an arcade in Soest. Both were cited as potential violations of Section 131 of the Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code), stating therein the illegality of representations which glorified violence. Increasingly realistic depictions of humans as targets for violence, both physical and sexual, necessitated a re-evaluation of existing legislation which made no such effort to criminalise imagery which ‘violated human dignity.’

Sixteen days later, the Federal Government answered the concerns of Die Grünen. The government had come to understand Lover Boy was installed in locations besides Soest, with the understanding that the PCB had been presented by an Italian importer in 1983 at Internationalen Fachmesse für Unterhaltungs- und Warenautomaten (The International Trade Fair for Amusement and Vending Machines) in Frankfurt. The specific board in Soest which drew initial concerns was sourced from a distributor in Dortmund. A March 1984 arcade game trade journal advertised Lover Boy as suitable for children, and thirty-two machines ended up being sold in North Rhine-Westphalia alone, and it came to be understood that Automaten-Selbstkontrolle (ASK) had been presented with incomplete information by which to rate its content; the content was egregious enough to exclude Lover Boy from any rating, leading to the existing machines being purchased and destroyed. A draft law was proposed to the Bundestag, stipulating that games of a violent sort must be prohibited from public areas frequented by children, and postulating that perhaps violent games should be banned wholesale in Germany.

A year later, in April 1985, Section 131 of the Strafgeseztbuch was amended to prohibit representations of violence, rather than just those which glorified it. Additionally, depictions of the ‘violation of human dignity’ were criminalised as well. The ASK became a permanent institution, officially regulating an industry that had, up to that point, been self-regulated.

The ban in Germany is easy to trace, but time and again, it is stated in other reviews and retrospectives that Lover Boy was banned globally outside of Japan with zero evidence offered to support that claim. Searches for “Lover Boy” and “Global Corporation Tokyo” in the United States Congressional Record, Historical Debates of the Parliament of Canada, British Cabinet Papers, CommonLii, Italian Senate record, New York Times, Globe & Mail, all turned up nothing. The German Wikipedia page also makes no mention of Lover Boy being banned anywhere outside of Germany.

Outside of the Bundestag record, some of the only other concrete information about Lover Boy is that it was brought to market by the same company that made 1983’s JoinEm, a non-erotic maze game, released under the name Global Corporation. The pinout and DIP switch documentation included with the Lover Boy PCB had Lover Boy handwritten on them. Weirding the situation further, a seeming bootleg of Lover Boy was released in Spain under the name Triki Triki, changing the developer name to DDT Enterprise, editing the copyright date to 1993.-nicht-jugendfrei-und-nicht-in-Mame/page10) The trail ends there.

If I were to posit a guess, the majority of the inaccurate claims about Lover Boy stem from a single GameFAQs review by defunct user ‘TheSAMMIES’. They claim, erroneously, that Lover Boy:

- Deals with aspects of rape beyond the penetrative act

- Has been banned globally

- Has better gameplay than 177

- Is slang for a man who lures underage women into prostitution (the term is only used in that manner in Dutch)

- Depicts only underage women

- Displays female genitalia

- Has only one maze

- Is of dark comedic value

None of that is true whatsoever. Their spurious falsehoods are on display in their review of 177 as well, claiming falsely:

- 177 is the police code for rape (it is simply the section of the Japanese Criminal Code which criminalises rape)

- RapeLay tackles rape more tactfully

- 177’s rape scenes show plant life and the night sky (they actually occur in a black void)

- Has controls in its rape scenes for getting onto Kotoe, penetrating her, building up sexual stamina (you actually just gyrate, the graphics barely animating)

- That 177 received a remake called 171 wherein Hideo is replaced by a squid monster, Kotoe by a maid (I have found no evidence of such a game existing)

Whether these ideas are being born purely from their mind, some misinterpretation of the realities of history, or whatever else, this individual seems to have irreparably tarnished the known history of Lover Boy, leading to prolonged repetition of the same incorrect claims. If there were any evidence to back up those ideas, wouldn’t they have shown themselves? Does it matter? Nobody cares about this game, nobody knows about it, can we fault the few who have documented it for their inaccuracies?

Yes, because it makes determining the truth all the harder. Yes, because it puts the onus of honestly on those who come after the fact. Yes, because just as these games are harmful in their depictions, speaking of them falsely is just as much of a disservice to history.

CW: Sexual assault. The four-letter ‘R-word’ is invoked repeatedly without censoring or obfuscation.

WHEN YOU CATCH A GIRL YOU MUST FIND RIGHT TIMING FOR MAXIMUM RESULT WHICH WILL BE SHOWN ON LOVE METER ACTION OF LOVE MAKING IS BY PUSH BUTTON. BEST TIMING WILL PRODUCE MOST ECSTATIC RESULTS ON FEMALE METER.

Lover Boy is functionally unremarkable, seemingly of as much import as Min Corp.’s Gumbo or Toaplan’s Pipi & Bibi’s. Unlike those games, however, Lover Boy is mired in obscurity, controversy, and a historiography that crumbles under scrutiny.

The gameplay is in line with other maze games of the early 1980s. The Lover Boy chases Lisa, Rosemarie, Linda, and Maria through a labyrinth while police officers and dogs track him. There are item pickups for points, and bottles of perfume which incense Lover Boy, boosting his speed dramatically. All the while, a rendition of the nursery rhyme しょうじょうじのたぬきばやし 「 Shoujouji no Tanukibayashi」 plays merrily. Getting near the girls causes them to run away while yelling HELP, touching them starts your digital assault. Like 177, the player tries to get their victim’s pleasure meter to top out before Lover Boy climaxes. Though 177 used directional inputs, Lover Boy simply has you tapping the button at a steady rhythm. Filling the LADY LOVE to the heart at the top has the women elate Oh~. Climaxing before she can has her yelling NO! and escaping, Lover Boy needing to chase her down again.

Though less explicitly stated in Lover Boy as compared to 177, we see the same rape myth being perpetuated, that of rape becoming a consensual sexual act should the victim reach orgasm. Since Lover Boy is an arcade game, designed to munch the yen of the aroused, there is no good ending to speak of here. The cycle continues in perpetuity until Lover Boy is put behind bars for good. This might suggest an inevitability to the rapist being caught and punished accordingly in due time, but the lives system inadvertently paints a picture wherein a sexual criminal is released and allowed to repeat their crimes with minimal repercussion. Lest we forget the harrowing injustice presented in 177’s manual, “even if he was prosecuted then, he would not be charged with a crime.” Capture is thus an inconvenience, nothing more.

In trying to find out more about Lover Boy, I came to find out it was cause for debate in the Deutscher Bundestag a year after its release. On March 26, 1984, parliamentary spokespersons for Die Grünen (The Greens) Marieluise Beck, Petra Kelly, and Otto Schily brought to the attention of the federal government the installation of light-gun games and Lover Boy in an arcade in Soest. Both were cited as potential violations of Section 131 of the Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code), stating therein the illegality of representations which glorified violence. Increasingly realistic depictions of humans as targets for violence, both physical and sexual, necessitated a re-evaluation of existing legislation which made no such effort to criminalise imagery which ‘violated human dignity.’

Sixteen days later, the Federal Government answered the concerns of Die Grünen. The government had come to understand Lover Boy was installed in locations besides Soest, with the understanding that the PCB had been presented by an Italian importer in 1983 at Internationalen Fachmesse für Unterhaltungs- und Warenautomaten (The International Trade Fair for Amusement and Vending Machines) in Frankfurt. The specific board in Soest which drew initial concerns was sourced from a distributor in Dortmund. A March 1984 arcade game trade journal advertised Lover Boy as suitable for children, and thirty-two machines ended up being sold in North Rhine-Westphalia alone, and it came to be understood that Automaten-Selbstkontrolle (ASK) had been presented with incomplete information by which to rate its content; the content was egregious enough to exclude Lover Boy from any rating, leading to the existing machines being purchased and destroyed. A draft law was proposed to the Bundestag, stipulating that games of a violent sort must be prohibited from public areas frequented by children, and postulating that perhaps violent games should be banned wholesale in Germany.

A year later, in April 1985, Section 131 of the Strafgeseztbuch was amended to prohibit representations of violence, rather than just those which glorified it. Additionally, depictions of the ‘violation of human dignity’ were criminalised as well. The ASK became a permanent institution, officially regulating an industry that had, up to that point, been self-regulated.

The ban in Germany is easy to trace, but time and again, it is stated in other reviews and retrospectives that Lover Boy was banned globally outside of Japan with zero evidence offered to support that claim. Searches for “Lover Boy” and “Global Corporation Tokyo” in the United States Congressional Record, Historical Debates of the Parliament of Canada, British Cabinet Papers, CommonLii, Italian Senate record, New York Times, Globe & Mail, all turned up nothing. The German Wikipedia page also makes no mention of Lover Boy being banned anywhere outside of Germany.

Outside of the Bundestag record, some of the only other concrete information about Lover Boy is that it was brought to market by the same company that made 1983’s JoinEm, a non-erotic maze game, released under the name Global Corporation. The pinout and DIP switch documentation included with the Lover Boy PCB had Lover Boy handwritten on them. Weirding the situation further, a seeming bootleg of Lover Boy was released in Spain under the name Triki Triki, changing the developer name to DDT Enterprise, editing the copyright date to 1993.-nicht-jugendfrei-und-nicht-in-Mame/page10) The trail ends there.

If I were to posit a guess, the majority of the inaccurate claims about Lover Boy stem from a single GameFAQs review by defunct user ‘TheSAMMIES’. They claim, erroneously, that Lover Boy:

- Deals with aspects of rape beyond the penetrative act

- Has been banned globally

- Has better gameplay than 177

- Is slang for a man who lures underage women into prostitution (the term is only used in that manner in Dutch)

- Depicts only underage women

- Displays female genitalia

- Has only one maze

- Is of dark comedic value

None of that is true whatsoever. Their spurious falsehoods are on display in their review of 177 as well, claiming falsely:

- 177 is the police code for rape (it is simply the section of the Japanese Criminal Code which criminalises rape)

- RapeLay tackles rape more tactfully

- 177’s rape scenes show plant life and the night sky (they actually occur in a black void)

- Has controls in its rape scenes for getting onto Kotoe, penetrating her, building up sexual stamina (you actually just gyrate, the graphics barely animating)

- That 177 received a remake called 171 wherein Hideo is replaced by a squid monster, Kotoe by a maid (I have found no evidence of such a game existing)

Whether these ideas are being born purely from their mind, some misinterpretation of the realities of history, or whatever else, this individual seems to have irreparably tarnished the known history of Lover Boy, leading to prolonged repetition of the same incorrect claims. If there were any evidence to back up those ideas, wouldn’t they have shown themselves? Does it matter? Nobody cares about this game, nobody knows about it, can we fault the few who have documented it for their inaccuracies?

Yes, because it makes determining the truth all the harder. Yes, because it puts the onus of honestly on those who come after the fact. Yes, because just as these games are harmful in their depictions, speaking of them falsely is just as much of a disservice to history.