Echo is so dark, so poignant, so emotionally enthralling and draining that a casual recommendation feels like reckless endangerment. I have no idea how anyone is “supposed” to react to this story. I don’t know that I want anyone to experience some of what it has to offer. I investigated Echo on a lark, then lost a week of my waking hours playing it. Echo is so profound and fresh and real that it changed my perspective on the nature of games, and where good games can come from. I respect it so much to say I love it feels wrong.

I’ll start by saying this is the first visual novel to demonstrate to me why “visual novel” is a legitimate gaming genre. I’ve played some Phoenix Wright games, and they’re great! They have a lot of reading, but also enough interactivity with that reading to feel like games. However, that interactivity is merely elongation of a linear narrative. The distance between when the player understands how to solve a puzzle vs when the game will allow the player to solve it can be agonizing. The similar Danganronpa series is filled with blatant insecurity regarding the fun of advancing a linear narrative, to the point of introducing a hoverboard minigame for answering a basic multiple choice question.

But surprise, those are both series closer to classic point and click adventure games than visual novels. They certainly have enough text to fill a novel or more, but so does every modern Animal Crossing and Fire Emblem. I thought about this while playing a SRPG with fully voiced story segments that can last hours between its levels of gameplay. It is considered a visual novel due to the sheer volume of its story segments, but the story is not the gameplay. The two are separate and distinct such that you could have a complete experience by skipping either. Echo feels like a visual novel because it makes reading the game mechanic.

Echo makes “reading” feel like a gameplay verb by carefully focusing its narrative, game structure, and writing style on the feeling of experiencing a mystery. Not the lock-and-key puzzle of solving a mystery, like a Phoenix Wright murder trial; the aura of mystery that emanates from existential horror.

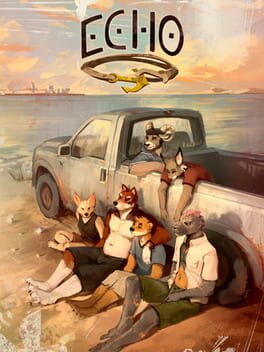

You play as a college student visiting your middle-of-nowhere small town over Spring Break, reuniting with five childhood friends after three years apart. You choose early on with which of the five friends you want to spend the week, a choice that dictates which of five stories you experience. As the week progresses, things take a turn for the spooky and the supernatural. Alone, each of Echo’s five routes are engaging, but their mysteries are not self-contained. Clues, context, and answers are sprinkled throughout every route, and all five are necessary for the full Echo experience.

It may sound simple on paper, but the craft is in the execution. The text of Echo would not work as a traditional novel separate from the trappings of being a game. Prose is expertly honed to the medium of its text box size. Descriptions are condensed so every idea is introduced, transitioned, or concluded one screen at time. Visual indications of who’s talking, who’s listening, who’s left the scene cut the need of so much “he said”-type structural grammar. Background images communicate changes in scenery, and the music punctuates changes in tone. The experience of reading is focused on the characters and their reactions at all times.

Interactivity arises from how much the game expects you to pay attention. It does not describe to you why a character acts a certain way. It expects you to infer the cast’s emotions based on your knowledge of what they should know and how they think. Functionally, this writing style allows the game to remain cryptic about context you would only glean from other routes. You are constantly evaluating whether your gaps in understanding are from not paying attention as a reader, or from context found in a different route. Although distended by hours, this task of continual inference arises from choices the player made. As such, gaps in your understanding feel like consequences of your actions as a player.

Echo offers few choices that matter, but their presence is always below the surface. New revelations make your mind wander to choices you’ve made in the past and anticipate choices you might have to make in the future. Continually feeling the friction of your player action’s consequences motivates you to keep reading. Wanting to alleviate that friction creates anticipation for which route you want to tackle next. This tension, of recontextualizing what you have done, what you have read, and why you want to read more in the future, is what elevates Echo as a visual novel. Echo justifies and excels within its classification as a game - it could not have existed in another medium.

Narrative tension can only exist when you’re invested in the characters, and I have to exclaim that the character writing is meticulous. Every character has a place and a history that exists separate from their plot relevance. Some routes will see you spend hours with characters that are only name-dropped or absent from others. I have met approximations of many of these people in real life with more specificity than an archetype. The naive young Christian man who gasps at swears, takes an hour in the shower, and makes a face when too much mayonnaise gets on his chicken sandwich. The witty girl with a bad home life who majored in psychology and can’t stop herself from correcting and analyzing every person and situation to hide from her own emotional reality. The writing is magnanimous enough to find the human dignity in meth addicts and honest enough to find the cruelty that blooms in the most vulnerable of friendships. Sometimes funny, often tragic, the character interactions alone were engaging enough for me to extend what was planned to be a cursory investigation into a complete route play-through.

The first route I finished truly shocked me. I was incoherent for hours afterwards trying to process it. Its multiple twists within its devastating climax retroactively reverberated through every assumption I had made about what kind of game I was playing, and how the game was presenting itself. Echo had weaponized my prejudices and assumptions as an outsider, (that I was playing some sort of cringey gay furry dating simulator), against me so subtly, so flawlessly, that I had been lead to focus on the wrong details about the player character and his relationships. Events and details I had passed off as perhaps careless usage of unfamiliar tropes were, in fact, completely accounted for by the narrative. The game knew exactly the moral weight and repercussions of the player character’s thoughts and actions, and I felt the fool for assuming they were handled lightly.

I do not fault myself for having low expectations, because it is so rare to find a work that understands the nature of evil. The limitations of evil, its narrative uses, the difference between the impartial evils of the universe and the unique flavors invented by human ingenuity. How Echo navigates the darkness it explores with deft and grace is impressive once you see the full list of taboo topics this game juggles. We have:

- Straight sex - Gay sex - Orgies - Rape - Murder - Dismemberment - Torture - Lynching - Homophobic violence - Racism - Suicide - Drowning - Gun violence - Domestic abuse - Child abuse - Minor endangerment - Drug abuse - Claustrophobic nightmare fuel - Arachnaphobic nightmare fuel - Suffocation nightmare fuel - Night terrors and sleep paralysis - Supernatural existential horror

I would not fault anyone for turning away at even one of these subjects; the potential for irresponsible mishandling is so high. Thankfully every heavy scenario is text-based, with no explicit drawings of nudity or violence. Although many, many terrible things happen, Echo is not interested in being misery or torture porn. It is a horror game with purpose.

For the different types of horror in Echo to work, it invests heavily in presenting the realities of its setting and cast. Fear comes both with familiarity of your neighbors and doubt in that same familiarity. Being lost alone on a road at night can be scary, but sometimes recognizing the trailer of the local crack dealer is scarier. Discrimination exists for gay characters, Mormons, immigrants, indiginous peoples, differing levels of wealth and education (and species, too, but not in a way that directly correlates to any of the other prejudices. I like that!Get owned, Zootopia). There’s an awareness of psychology and sociology in the writing more than saying a character “has anxiety” or a certain ancestry, with authentic dramatization given to its characters’ intersectionality.

Echo understands monsters are not made in a vacuum. It understands the lack of economic prospects, the lack of law enforcement, the lack of community that lead people to destructive tendencies. Stupidity, ignorance, curiosity, fear, trauma - these combine to make forms of evil that are real and palpable. The most heinous actions in Echo are committed by people. They’re unaware or uncaring of the trauma they cause to others, compartmentalizing or justifying what they do. The real horror is how, left undetected, without a goal, and without avarice, vices can continue and escalate. Just doing what comes naturally, when unchecked, warps someone’s sense of reality to reach equilibrium with the environment around them, striking the balance of perpetuating evils without attracting attention. Not out of shame or fear, but the base desire to be left well enough alone.

(Please don’t misunderstand, Echo is not so quaint as to say “what if people were the real monsters all along?” We have genuine spooks. I’m too old and dead inside to be scared of ghosts, but for a week after I finished the game, every night after I was in bed and turned off the lights, I saw one of the spooks from this game. My brain associated it with darkness that strongly. So, uh, take that as my spoiler free review of the supernatural horrors this game contains. If I were a teen I would 100% have not finished this game nor slept for a month.)

I also don’t want to misrepresent Echo as being all horror all the time. Echo’s horror works because its characters feel real. They’re funny. They’re lame. They have sex for bad reasons and have instant regret. There are no paragons of virtue. Their relationships suck.

I don’t like these characters. I don’t love these characters. I would not want to be friends with any of them. But I know these characters. I understand them. For some of them, my familiarity borders on contempt or disgust.

But after finishing the game, I miss them. I miss them in the way all good fiction makes you miss watching people make life-defining decisions and fight for lasting change. I miss the constant revelations both mundane and profound. I miss the feeling you are witnessing the most important moments of someone’s life, regardless if it ends in tragedy.

I felt something different after each of the five stories. One sent me into the limbo of wanting to cry. Not as in, I felt close to crying. Far from it. It was that rare feeling where your emotions are intense and inscrutable, and you long for the simplicity of emotional understanding, the catharsis that comes from crying. But what you feel is complex and hidden, making you feel a stranger to yourself. It was only after ruminating on everything from all five stories that I distilled what Echo is about.

Echo grasps at the face of evil because it posits an asymmetry of our imperfect world: that the opposite of evil isn’t goodness, or happiness, but meaning. That moving away from evil looks like becoming a slightly less broken version of ourselves, even if the process makes us sadder. Echo captures that sense of longing and sorrow for thinking about what could have been. Not in a rosy sense, centered around nostalgia, but the pain that comes from recognizing too late how an environment has been suffocating you. Or tasting what it feels like to be properly nurtured after years of ignorance of your own neglect. And the fear that comes from realizing you have outgrown all your comforts, and everyone you ever loved in your life, leaving you stranded and clueless on how to rely on yourself.

The horrors in Echo, while effective, are background to framing the concept that even if everything you see is fake, the emotions you have are real. It doesn’t matter if the danger was imagined. It doesn’t matter if the monsters we fear in the dark are real. The shared experiences with others, and what you learn about each other in times of crisis, what you learn about yourself, is the reality that matters. As such, the endings all felt satisfying even if, on paper, so much was left unexplained. Because knowing what went bump in the night does not matter as much as the friends who came to your aid, the regret you feel over your inactions, or the resolve cultivated within yourself. After a certain threshold of loss and pain, you don’t care about knowing why they happened. You have to deal with the logistics of those wounds, regardless of whether they scar or heal.

I miraculously got all the “good” endings in every route with good and bad endings. Going back to replay some of the choices that lead to “bad” endings solidified for me how the game was enforcing its messages. The choices that tempt you away from the “good” endings are ones that let you cheat yourself, where you seek happiness or convenience over doing what is right. The “good” endings are often still filled with tragedy. But the characters might have truth, self-knowledge, or fewer regrets than if you chose differently.

In my rating system, I reserve 5/5 stars for the pinnacle of the medium. At the time of this review, it is the 13th game I’ve awarded this honor. It is not flawless, but for a game released for free, why even bother saying so. It took me many agonizing days writing this review, and I felt very much like Anton Ego in my internal struggle to admit I could not give this game less than full marks.Which I also internally found very funny since I have like 5 followers and am not the most respected critic in France lmao

For me, Echo is a new type of game, and as said by Anton, it needs defenders and friends. I went in expecting to bounce at some weird gay furry cringe, and instead cringed because it was more human and relatable than most games I’ve played. I had no idea furry-ness had reached such organization in creative endeavors as to create entire games, much less that this is one of among an entire “furry visual novel” sub-genre. (There are hundreds of projects like this one! Who knew?) I’m truly fascinated by the concept of games being funded on patreon over the course of years, released for free after they’re completed. Art completely unbeholden to any form of external review, profit motive, or timetable. Games that are built with and influenced by their supportive community. It’s a model that feels so radical as to be non-functional, yet this single proof of concept is enough to rekindle my imagination for the future of the medium.

I’ll start by saying this is the first visual novel to demonstrate to me why “visual novel” is a legitimate gaming genre. I’ve played some Phoenix Wright games, and they’re great! They have a lot of reading, but also enough interactivity with that reading to feel like games. However, that interactivity is merely elongation of a linear narrative. The distance between when the player understands how to solve a puzzle vs when the game will allow the player to solve it can be agonizing. The similar Danganronpa series is filled with blatant insecurity regarding the fun of advancing a linear narrative, to the point of introducing a hoverboard minigame for answering a basic multiple choice question.

But surprise, those are both series closer to classic point and click adventure games than visual novels. They certainly have enough text to fill a novel or more, but so does every modern Animal Crossing and Fire Emblem. I thought about this while playing a SRPG with fully voiced story segments that can last hours between its levels of gameplay. It is considered a visual novel due to the sheer volume of its story segments, but the story is not the gameplay. The two are separate and distinct such that you could have a complete experience by skipping either. Echo feels like a visual novel because it makes reading the game mechanic.

Echo makes “reading” feel like a gameplay verb by carefully focusing its narrative, game structure, and writing style on the feeling of experiencing a mystery. Not the lock-and-key puzzle of solving a mystery, like a Phoenix Wright murder trial; the aura of mystery that emanates from existential horror.

You play as a college student visiting your middle-of-nowhere small town over Spring Break, reuniting with five childhood friends after three years apart. You choose early on with which of the five friends you want to spend the week, a choice that dictates which of five stories you experience. As the week progresses, things take a turn for the spooky and the supernatural. Alone, each of Echo’s five routes are engaging, but their mysteries are not self-contained. Clues, context, and answers are sprinkled throughout every route, and all five are necessary for the full Echo experience.

It may sound simple on paper, but the craft is in the execution. The text of Echo would not work as a traditional novel separate from the trappings of being a game. Prose is expertly honed to the medium of its text box size. Descriptions are condensed so every idea is introduced, transitioned, or concluded one screen at time. Visual indications of who’s talking, who’s listening, who’s left the scene cut the need of so much “he said”-type structural grammar. Background images communicate changes in scenery, and the music punctuates changes in tone. The experience of reading is focused on the characters and their reactions at all times.

Interactivity arises from how much the game expects you to pay attention. It does not describe to you why a character acts a certain way. It expects you to infer the cast’s emotions based on your knowledge of what they should know and how they think. Functionally, this writing style allows the game to remain cryptic about context you would only glean from other routes. You are constantly evaluating whether your gaps in understanding are from not paying attention as a reader, or from context found in a different route. Although distended by hours, this task of continual inference arises from choices the player made. As such, gaps in your understanding feel like consequences of your actions as a player.

Echo offers few choices that matter, but their presence is always below the surface. New revelations make your mind wander to choices you’ve made in the past and anticipate choices you might have to make in the future. Continually feeling the friction of your player action’s consequences motivates you to keep reading. Wanting to alleviate that friction creates anticipation for which route you want to tackle next. This tension, of recontextualizing what you have done, what you have read, and why you want to read more in the future, is what elevates Echo as a visual novel. Echo justifies and excels within its classification as a game - it could not have existed in another medium.

Narrative tension can only exist when you’re invested in the characters, and I have to exclaim that the character writing is meticulous. Every character has a place and a history that exists separate from their plot relevance. Some routes will see you spend hours with characters that are only name-dropped or absent from others. I have met approximations of many of these people in real life with more specificity than an archetype. The naive young Christian man who gasps at swears, takes an hour in the shower, and makes a face when too much mayonnaise gets on his chicken sandwich. The witty girl with a bad home life who majored in psychology and can’t stop herself from correcting and analyzing every person and situation to hide from her own emotional reality. The writing is magnanimous enough to find the human dignity in meth addicts and honest enough to find the cruelty that blooms in the most vulnerable of friendships. Sometimes funny, often tragic, the character interactions alone were engaging enough for me to extend what was planned to be a cursory investigation into a complete route play-through.

The first route I finished truly shocked me. I was incoherent for hours afterwards trying to process it. Its multiple twists within its devastating climax retroactively reverberated through every assumption I had made about what kind of game I was playing, and how the game was presenting itself. Echo had weaponized my prejudices and assumptions as an outsider, (that I was playing some sort of cringey gay furry dating simulator), against me so subtly, so flawlessly, that I had been lead to focus on the wrong details about the player character and his relationships. Events and details I had passed off as perhaps careless usage of unfamiliar tropes were, in fact, completely accounted for by the narrative. The game knew exactly the moral weight and repercussions of the player character’s thoughts and actions, and I felt the fool for assuming they were handled lightly.

I do not fault myself for having low expectations, because it is so rare to find a work that understands the nature of evil. The limitations of evil, its narrative uses, the difference between the impartial evils of the universe and the unique flavors invented by human ingenuity. How Echo navigates the darkness it explores with deft and grace is impressive once you see the full list of taboo topics this game juggles. We have:

- Straight sex - Gay sex - Orgies - Rape - Murder - Dismemberment - Torture - Lynching - Homophobic violence - Racism - Suicide - Drowning - Gun violence - Domestic abuse - Child abuse - Minor endangerment - Drug abuse - Claustrophobic nightmare fuel - Arachnaphobic nightmare fuel - Suffocation nightmare fuel - Night terrors and sleep paralysis - Supernatural existential horror

I would not fault anyone for turning away at even one of these subjects; the potential for irresponsible mishandling is so high. Thankfully every heavy scenario is text-based, with no explicit drawings of nudity or violence. Although many, many terrible things happen, Echo is not interested in being misery or torture porn. It is a horror game with purpose.

For the different types of horror in Echo to work, it invests heavily in presenting the realities of its setting and cast. Fear comes both with familiarity of your neighbors and doubt in that same familiarity. Being lost alone on a road at night can be scary, but sometimes recognizing the trailer of the local crack dealer is scarier. Discrimination exists for gay characters, Mormons, immigrants, indiginous peoples, differing levels of wealth and education (and species, too, but not in a way that directly correlates to any of the other prejudices. I like that!

Echo understands monsters are not made in a vacuum. It understands the lack of economic prospects, the lack of law enforcement, the lack of community that lead people to destructive tendencies. Stupidity, ignorance, curiosity, fear, trauma - these combine to make forms of evil that are real and palpable. The most heinous actions in Echo are committed by people. They’re unaware or uncaring of the trauma they cause to others, compartmentalizing or justifying what they do. The real horror is how, left undetected, without a goal, and without avarice, vices can continue and escalate. Just doing what comes naturally, when unchecked, warps someone’s sense of reality to reach equilibrium with the environment around them, striking the balance of perpetuating evils without attracting attention. Not out of shame or fear, but the base desire to be left well enough alone.

(Please don’t misunderstand, Echo is not so quaint as to say “what if people were the real monsters all along?” We have genuine spooks. I’m too old and dead inside to be scared of ghosts, but for a week after I finished the game, every night after I was in bed and turned off the lights, I saw one of the spooks from this game. My brain associated it with darkness that strongly. So, uh, take that as my spoiler free review of the supernatural horrors this game contains. If I were a teen I would 100% have not finished this game nor slept for a month.)

I also don’t want to misrepresent Echo as being all horror all the time. Echo’s horror works because its characters feel real. They’re funny. They’re lame. They have sex for bad reasons and have instant regret. There are no paragons of virtue. Their relationships suck.

I don’t like these characters. I don’t love these characters. I would not want to be friends with any of them. But I know these characters. I understand them. For some of them, my familiarity borders on contempt or disgust.

But after finishing the game, I miss them. I miss them in the way all good fiction makes you miss watching people make life-defining decisions and fight for lasting change. I miss the constant revelations both mundane and profound. I miss the feeling you are witnessing the most important moments of someone’s life, regardless if it ends in tragedy.

I felt something different after each of the five stories. One sent me into the limbo of wanting to cry. Not as in, I felt close to crying. Far from it. It was that rare feeling where your emotions are intense and inscrutable, and you long for the simplicity of emotional understanding, the catharsis that comes from crying. But what you feel is complex and hidden, making you feel a stranger to yourself. It was only after ruminating on everything from all five stories that I distilled what Echo is about.

Echo grasps at the face of evil because it posits an asymmetry of our imperfect world: that the opposite of evil isn’t goodness, or happiness, but meaning. That moving away from evil looks like becoming a slightly less broken version of ourselves, even if the process makes us sadder. Echo captures that sense of longing and sorrow for thinking about what could have been. Not in a rosy sense, centered around nostalgia, but the pain that comes from recognizing too late how an environment has been suffocating you. Or tasting what it feels like to be properly nurtured after years of ignorance of your own neglect. And the fear that comes from realizing you have outgrown all your comforts, and everyone you ever loved in your life, leaving you stranded and clueless on how to rely on yourself.

The horrors in Echo, while effective, are background to framing the concept that even if everything you see is fake, the emotions you have are real. It doesn’t matter if the danger was imagined. It doesn’t matter if the monsters we fear in the dark are real. The shared experiences with others, and what you learn about each other in times of crisis, what you learn about yourself, is the reality that matters. As such, the endings all felt satisfying even if, on paper, so much was left unexplained. Because knowing what went bump in the night does not matter as much as the friends who came to your aid, the regret you feel over your inactions, or the resolve cultivated within yourself. After a certain threshold of loss and pain, you don’t care about knowing why they happened. You have to deal with the logistics of those wounds, regardless of whether they scar or heal.

I miraculously got all the “good” endings in every route with good and bad endings. Going back to replay some of the choices that lead to “bad” endings solidified for me how the game was enforcing its messages. The choices that tempt you away from the “good” endings are ones that let you cheat yourself, where you seek happiness or convenience over doing what is right. The “good” endings are often still filled with tragedy. But the characters might have truth, self-knowledge, or fewer regrets than if you chose differently.

In my rating system, I reserve 5/5 stars for the pinnacle of the medium. At the time of this review, it is the 13th game I’ve awarded this honor. It is not flawless, but for a game released for free, why even bother saying so. It took me many agonizing days writing this review, and I felt very much like Anton Ego in my internal struggle to admit I could not give this game less than full marks.

For me, Echo is a new type of game, and as said by Anton, it needs defenders and friends. I went in expecting to bounce at some weird gay furry cringe, and instead cringed because it was more human and relatable than most games I’ve played. I had no idea furry-ness had reached such organization in creative endeavors as to create entire games, much less that this is one of among an entire “furry visual novel” sub-genre. (There are hundreds of projects like this one! Who knew?) I’m truly fascinated by the concept of games being funded on patreon over the course of years, released for free after they’re completed. Art completely unbeholden to any form of external review, profit motive, or timetable. Games that are built with and influenced by their supportive community. It’s a model that feels so radical as to be non-functional, yet this single proof of concept is enough to rekindle my imagination for the future of the medium.

Reviewed on May 05, 2022

2 Comments

You know, I'm not a particularly literate person

BUT GODAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAMN

Absolutely fantastic work. I had no idea this game existed, but you bet your bottom dollar it's on my radar now. Thank you.

BUT GODAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAMN

Absolutely fantastic work. I had no idea this game existed, but you bet your bottom dollar it's on my radar now. Thank you.

tdstr

1 year ago

Also, (https://rot13.com/ to mask vague spoilers): v yvxr ubj V’ir tbg onfvpnyyl ab pyhr jung ebhgr lbh qvq svefg rira jvgu gung qrfpevcgvba lbh tnir bs vg yby. “zhygvcyr gjvfgf jvgu n qrinfgngvat pyvznk” vf yvxr, rirel ebhgr unun