I have beaten Streets of Rage 2 a bunch of times since completing Streets of Rage 4 a bunch of times, because Streets of Rage 4 more or less trains you on how to play Streets of Rage 1, 2 & 3 correctly.

Game fans, myself included, often bounce off of old arcade-style beat ‘em ups because they can initially appear impossible to beat without reaching for the save-state. But we often forget Streets of Rage 2 and its contemporaries were designed to be appreciated again and again until you reached some state of mastery. Streets of Rage 2 was designed to be bought by your mum for £50 and played by you every day after school until Mr. X finally ate dirt. Streets of Rage 2 was not designed to be included in a 40-game Mega Drive all-you-can-game buffet that you can buy on Steam for £2.49 right now or enjoy for “free” as part of the Nintendo Switch Online Sega Mega Drive Expansion Package Plus for Nintendo Switch or whatever it’s called. You don’t have time to try Stage 3 of Streets of Rage 2 again - you need to go over there and play ToeJam & Earl 2 in its original Japanese translation, for some reason!

No, I say! Stay here and learn your Streets of Rage, kid. Because mastering a beam ‘em up always feels great! A good beam ‘em up often boils down to something between a fighting game and a puzzle game - figuring out what each enemy’s weakness is, considering the order in which to exploit these weaknesses, and then executing the correct badass moves under pressure from the advancing mob. It’s like Tetris, but the blocks are made out of punches and broken bottles. It’s beautiful.

This time round on Streets of Rage 2, I sleepwalked through the opening few stages without taking a single hit. I didn’t even realise I’d done it until I checked out how many lives I’d accumulated. Apparently I’d just been effortlessly side-stepping Galsias and out-ranging Donovans without even consciously doing it, applying some hybrid martial art that stands somewhere between the so-called “Tetris effect” and that bit in The Matrix Reloaded where Neo is just effortlessly ducking and stepping those Agent Smiths. Pro Gamer Shit.

Just kidding. I don’t consider myself a pro at Streets of Rage 2 by any stretch - but after playing through the game six or seven times with my brain turned on, I realised Streets of Rage 2 had trained me so well that I’d internalised all the natures and patterns of the game’s opening enemies. Folks, that’s some Good Game Design! And we haven’t even talked about the Good Design of the music or the artwork yet!

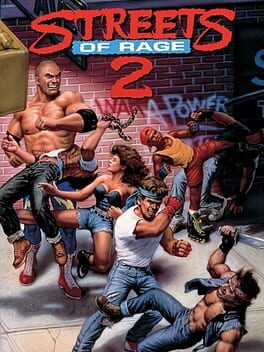

One thing this play-through of Streets of Rage 2 made me think about was how well Streets of Rage 2 serves as a perfect historical relic of its era and specific place in that era - a pixel-art tableau of early 1990s house/rave/hip hop culture on the east coast of America. More specifically, early 1990s house/rave/hip hop culture on the east coast of America as viewed by an incredibly talented, classically-trained Japanese designer and composer who could see that computers and video games represented the future. Streets of Rage 2 is how people outside of America saw this side of America in this era, and every era since - through film and music and video games. It’s fascinating to see what essential truths and dreams made it across the ocean to us. I think this game has genuine cultural worth that scholars in halls grander than Backloggd’s will one day celebrate.

About 8 years after Streets of Rage 2 made its own history, Japan’s Takeshi Kitano made a film called Brother. Brother was Takeshi Kitano’s first film outside of Japan, and was set in Los Angeles with a half-American, half-Japanese cast. As a hands-on director, writer and actor, there’s no doubt that Brother represents Kitano’s vision of Los Angeles and America at large. Check it out! It’s good! Exactly like Streets of Rage 2, Brother serves as a celluloid time capsule of America’s international cultural impact and influence at a specific point in time - and it’s quite striking how much had changed in the space of the 8 years between 1992 and the year 2000. Brother is one of Kitano’s lesser-appreciated films, but I think that film has genuine cultural worth that scholars in halls grander than Letterboxd’s will one day celebrate.

So, there you have it - an arcade beat ‘em up game with beautiful, artistic complexity of beat ‘em up game design, sharing bytes in the same cartridge with one of the most important cultural artefacts of the early 1990s. Still wanna fuck around with Toe Jam & Earl? C’mon man.

Game fans, myself included, often bounce off of old arcade-style beat ‘em ups because they can initially appear impossible to beat without reaching for the save-state. But we often forget Streets of Rage 2 and its contemporaries were designed to be appreciated again and again until you reached some state of mastery. Streets of Rage 2 was designed to be bought by your mum for £50 and played by you every day after school until Mr. X finally ate dirt. Streets of Rage 2 was not designed to be included in a 40-game Mega Drive all-you-can-game buffet that you can buy on Steam for £2.49 right now or enjoy for “free” as part of the Nintendo Switch Online Sega Mega Drive Expansion Package Plus for Nintendo Switch or whatever it’s called. You don’t have time to try Stage 3 of Streets of Rage 2 again - you need to go over there and play ToeJam & Earl 2 in its original Japanese translation, for some reason!

No, I say! Stay here and learn your Streets of Rage, kid. Because mastering a beam ‘em up always feels great! A good beam ‘em up often boils down to something between a fighting game and a puzzle game - figuring out what each enemy’s weakness is, considering the order in which to exploit these weaknesses, and then executing the correct badass moves under pressure from the advancing mob. It’s like Tetris, but the blocks are made out of punches and broken bottles. It’s beautiful.

This time round on Streets of Rage 2, I sleepwalked through the opening few stages without taking a single hit. I didn’t even realise I’d done it until I checked out how many lives I’d accumulated. Apparently I’d just been effortlessly side-stepping Galsias and out-ranging Donovans without even consciously doing it, applying some hybrid martial art that stands somewhere between the so-called “Tetris effect” and that bit in The Matrix Reloaded where Neo is just effortlessly ducking and stepping those Agent Smiths. Pro Gamer Shit.

Just kidding. I don’t consider myself a pro at Streets of Rage 2 by any stretch - but after playing through the game six or seven times with my brain turned on, I realised Streets of Rage 2 had trained me so well that I’d internalised all the natures and patterns of the game’s opening enemies. Folks, that’s some Good Game Design! And we haven’t even talked about the Good Design of the music or the artwork yet!

One thing this play-through of Streets of Rage 2 made me think about was how well Streets of Rage 2 serves as a perfect historical relic of its era and specific place in that era - a pixel-art tableau of early 1990s house/rave/hip hop culture on the east coast of America. More specifically, early 1990s house/rave/hip hop culture on the east coast of America as viewed by an incredibly talented, classically-trained Japanese designer and composer who could see that computers and video games represented the future. Streets of Rage 2 is how people outside of America saw this side of America in this era, and every era since - through film and music and video games. It’s fascinating to see what essential truths and dreams made it across the ocean to us. I think this game has genuine cultural worth that scholars in halls grander than Backloggd’s will one day celebrate.

About 8 years after Streets of Rage 2 made its own history, Japan’s Takeshi Kitano made a film called Brother. Brother was Takeshi Kitano’s first film outside of Japan, and was set in Los Angeles with a half-American, half-Japanese cast. As a hands-on director, writer and actor, there’s no doubt that Brother represents Kitano’s vision of Los Angeles and America at large. Check it out! It’s good! Exactly like Streets of Rage 2, Brother serves as a celluloid time capsule of America’s international cultural impact and influence at a specific point in time - and it’s quite striking how much had changed in the space of the 8 years between 1992 and the year 2000. Brother is one of Kitano’s lesser-appreciated films, but I think that film has genuine cultural worth that scholars in halls grander than Letterboxd’s will one day celebrate.

So, there you have it - an arcade beat ‘em up game with beautiful, artistic complexity of beat ‘em up game design, sharing bytes in the same cartridge with one of the most important cultural artefacts of the early 1990s. Still wanna fuck around with Toe Jam & Earl? C’mon man.