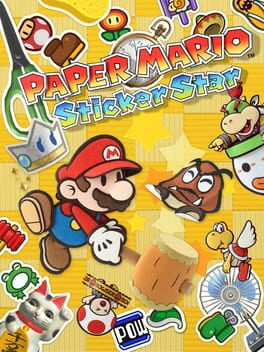

Paper Mario Sticker Star was a landmark experience in my relationship with video games.

At one point in time, Paper Mario: the Thousand Year Door was my favorite game. I didn’t know what a JRPG was, and from how I heard people talk at school, thought it had something to do with the war in Iraq. I hadn’t played Chrono Trigger yet. But anything with Mario on it passed my parents' arbitrary content filtration, so Paper Mario: the Thousand Year Door remained a unique game that pressed multiple buttons I liked. The art style spoke to me as an aspiring vector graphic artist. There was strategy, there was story, with enough player engagement and metatextual dressing to sell me on turn-based combat. It was funny, it was cute, with just enough depth to help me graduate from the simplicity of the Mario platformers I was used to.

Super Paper Mario was fine. I knew it was a different genre before it came out, which offset my disappointment somewhat, enough that I never said out loud, “this art style is lame.” My Smash Bros. friend thought it was hilarious, so I liked it, too. I got my sister to play it, in an attempt to convince myself to love it. It didn’t work, but Super Paper Mario became the first game she ever finished. I was happy for her. So I never said out loud, “this game should have been better.” But I felt it.

Sticker Star came out during a long period when I didn’t play video games. I didn’t get to it for years. By the time it was $10 on clearance, there were other games I liked. Maybe Xenoblade Chronicles or Fire Emblem Awakening were my new favorite games. But now Paper Mario: the Thousand Year Door had ~nostalgia~ status, before I knew what that word meant, much less what it meant for me.

I played all of Sticker Star. I finished it. I remembered and remember nothing about it. I felt nothing. Or thought I felt nothing. Until I saw empty achievement podiums in the post-game inviting me to do a bunch of pointless grindy bullshit to check off some checklists.

My first reaction was “oh, more content! More Paper Mario!” until my brain processed what the game was asking of me. Find all the trinkets? Win a lottery 50 times? Collect 10,000 coins?

I said out loud, “Why would anyone do that?”

Then a profound realization washed over me. I did not like this game. I did not enjoy any of my time with this game. I had finished this entire game precisely because of my remembered love for a different game with the same name. A love that had at once been unexamined, treasured, and rendered featureless and sourceless with time.

I stared at the achievement markers, not yet knowing what an achievement was, and felt an inscrutable feeling of dread and betrayal. This game was bad. But beyond the game being bad, Sticker Star was also behaving as if it were unaware it was bad. Smash Bros. had checklists, but they unlocked new stages, new characters. Those checklists were crude interfaces for unlocking fun surprises. This was just… homework.

But why would Nintendo give me homework? Why would Mario give me homework? And why would a real life human do that homework if they weren’t getting graded or paid? I quietly saved the game, returned it to its case, and closed my 3DS, more pensive and alone feeling than I was expecting to feel that day. I told no one about this experience. I told no one I had even played the game. My Smash Bros. friend was gone and married at that point, anyway.

I’d watched people at school play bad flash games, so I knew bad games existed. But they seemed to poke fun at themselves, aware of their own disposability. This was the first time my childish, uncritical brain was forced to confront the reality that bad games could come from Brands™ made by Adults. Because the more I stewed on why the idea of those achievements felt like homework, the more I realized the entire experience of playing the game felt like homework. Stripped of context, stripped of story, the basic actions of the game were straight unfun to play. But that meant the presentation hadn’t made the game fun, it had only been a distraction from the neutral hell of paying money to do homework for zero learning or recognition.

I don’t want to oversell Sticker Star’s importance in my developing critical facilities, but it is the clearest turning point of my self-awareness with a game before several of my behaviors changed. I stopped getting excited for games before their release. I stopped visiting IGN - they’d given this game an 8.3! I stopped saying a game was among my favorites if I couldn’t remember why. I actually finished Xenoblade Chronicles. That ending suuuuucked, and the game stopped being in my top 10.

There’s a good chance many of these changes would have come about as side-effects of growing up. But maturity and wisdom are not guaranteed with age. New ‘bad’ Paper Mario games keep coming out, and I see its “fan” base go through phases of evangelical rage and disappointment with every release. Fans who never learned the lessons that Sticker Star offered, that fans should sprout up around products, and not that products will be made for fans.

I have no rage for Sticker Star. I successfully recognized that Sticker Star did not deserve to tap into the well of emotions that had been drilled by the Thousand Year Door. With that realization, the bubble of nostalgia around the Thousand Year Door popped, its warm glow confined to its own identity instead of allowed to exist as an emotionally ethereal entity that could bless and inhabit other games. With that skill obtained, other nostalgia bubbles began to deflate over the years until none remained. It was a melancholic mental transformation, but with it came a confidence that the games I liked were Actually Good instead of emotional echoes of a previous self.

The Paper Mario series effectively taught me how the commodification of game series changes its identity. I’m tempted to say “and robs it of its soul,” but the new bad Paper Mario games have a different soul. A beige-colored soul. A market-tested soul that sets sales records, with legs enough that whatever Paper Mario came out on the Switch can probably tap into nostalgia people have for Sticker Star. (A concept that belongs in my personal version of hell.)

It’s only fitting that Mario, who introduced me to platforming, racing, and JRPGs, would also be the one to teach me about the dystopian rot of corporate game production.

I am not grateful.

At one point in time, Paper Mario: the Thousand Year Door was my favorite game. I didn’t know what a JRPG was, and from how I heard people talk at school, thought it had something to do with the war in Iraq. I hadn’t played Chrono Trigger yet. But anything with Mario on it passed my parents' arbitrary content filtration, so Paper Mario: the Thousand Year Door remained a unique game that pressed multiple buttons I liked. The art style spoke to me as an aspiring vector graphic artist. There was strategy, there was story, with enough player engagement and metatextual dressing to sell me on turn-based combat. It was funny, it was cute, with just enough depth to help me graduate from the simplicity of the Mario platformers I was used to.

Super Paper Mario was fine. I knew it was a different genre before it came out, which offset my disappointment somewhat, enough that I never said out loud, “this art style is lame.” My Smash Bros. friend thought it was hilarious, so I liked it, too. I got my sister to play it, in an attempt to convince myself to love it. It didn’t work, but Super Paper Mario became the first game she ever finished. I was happy for her. So I never said out loud, “this game should have been better.” But I felt it.

Sticker Star came out during a long period when I didn’t play video games. I didn’t get to it for years. By the time it was $10 on clearance, there were other games I liked. Maybe Xenoblade Chronicles or Fire Emblem Awakening were my new favorite games. But now Paper Mario: the Thousand Year Door had ~nostalgia~ status, before I knew what that word meant, much less what it meant for me.

I played all of Sticker Star. I finished it. I remembered and remember nothing about it. I felt nothing. Or thought I felt nothing. Until I saw empty achievement podiums in the post-game inviting me to do a bunch of pointless grindy bullshit to check off some checklists.

My first reaction was “oh, more content! More Paper Mario!” until my brain processed what the game was asking of me. Find all the trinkets? Win a lottery 50 times? Collect 10,000 coins?

I said out loud, “Why would anyone do that?”

Then a profound realization washed over me. I did not like this game. I did not enjoy any of my time with this game. I had finished this entire game precisely because of my remembered love for a different game with the same name. A love that had at once been unexamined, treasured, and rendered featureless and sourceless with time.

I stared at the achievement markers, not yet knowing what an achievement was, and felt an inscrutable feeling of dread and betrayal. This game was bad. But beyond the game being bad, Sticker Star was also behaving as if it were unaware it was bad. Smash Bros. had checklists, but they unlocked new stages, new characters. Those checklists were crude interfaces for unlocking fun surprises. This was just… homework.

But why would Nintendo give me homework? Why would Mario give me homework? And why would a real life human do that homework if they weren’t getting graded or paid? I quietly saved the game, returned it to its case, and closed my 3DS, more pensive and alone feeling than I was expecting to feel that day. I told no one about this experience. I told no one I had even played the game. My Smash Bros. friend was gone and married at that point, anyway.

I’d watched people at school play bad flash games, so I knew bad games existed. But they seemed to poke fun at themselves, aware of their own disposability. This was the first time my childish, uncritical brain was forced to confront the reality that bad games could come from Brands™ made by Adults. Because the more I stewed on why the idea of those achievements felt like homework, the more I realized the entire experience of playing the game felt like homework. Stripped of context, stripped of story, the basic actions of the game were straight unfun to play. But that meant the presentation hadn’t made the game fun, it had only been a distraction from the neutral hell of paying money to do homework for zero learning or recognition.

I don’t want to oversell Sticker Star’s importance in my developing critical facilities, but it is the clearest turning point of my self-awareness with a game before several of my behaviors changed. I stopped getting excited for games before their release. I stopped visiting IGN - they’d given this game an 8.3! I stopped saying a game was among my favorites if I couldn’t remember why. I actually finished Xenoblade Chronicles. That ending suuuuucked, and the game stopped being in my top 10.

There’s a good chance many of these changes would have come about as side-effects of growing up. But maturity and wisdom are not guaranteed with age. New ‘bad’ Paper Mario games keep coming out, and I see its “fan” base go through phases of evangelical rage and disappointment with every release. Fans who never learned the lessons that Sticker Star offered, that fans should sprout up around products, and not that products will be made for fans.

I have no rage for Sticker Star. I successfully recognized that Sticker Star did not deserve to tap into the well of emotions that had been drilled by the Thousand Year Door. With that realization, the bubble of nostalgia around the Thousand Year Door popped, its warm glow confined to its own identity instead of allowed to exist as an emotionally ethereal entity that could bless and inhabit other games. With that skill obtained, other nostalgia bubbles began to deflate over the years until none remained. It was a melancholic mental transformation, but with it came a confidence that the games I liked were Actually Good instead of emotional echoes of a previous self.

The Paper Mario series effectively taught me how the commodification of game series changes its identity. I’m tempted to say “and robs it of its soul,” but the new bad Paper Mario games have a different soul. A beige-colored soul. A market-tested soul that sets sales records, with legs enough that whatever Paper Mario came out on the Switch can probably tap into nostalgia people have for Sticker Star. (A concept that belongs in my personal version of hell.)

It’s only fitting that Mario, who introduced me to platforming, racing, and JRPGs, would also be the one to teach me about the dystopian rot of corporate game production.

I am not grateful.

Bavoom

1 year ago