One of the weirdest consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a fundamental shift in how art can be and is consumed. The pre-vaccine pandemic prohibited the perusal of physical artworks since galleries are enclosed spaces which, at times, necessitate a close proximity with others outside of your cohort. With how stringent the atmospheric conditions are in most galleries, the idea of introducing additional moisture through people with COVID-induced sniffles was certainly a concern for many curators. With the rest of the world moving to primarily online modes of functioning, the realm of art followed suit with a greater focus on digitisation and accessibility. With a 77% drop in museum attendance in 2020, cultural spaces were afforded the rare opportunity to strip the walls of famous works so they could be catalogued more extensively, scanned in higher quality than ever before, and be presented globally over the internet.¹ As a part of Google's own AR initiatives, paintings and sculptures could be virtually projected into one's own home to impart a sense of scale, and to allow viewers to get incredibly close to the artwork.² These searchable catalogues and viewable works are great in theory, particularly from an accessibility standpoint, but the glut of artwork available means a lesser focus on the provenance of particular works and artists, and a consumption pattern akin to scrolling through an Instagram feed. One of the most important parts of the gallery experience, personally, is the contextualisation of more renowned works amongst similar pieces which are largely omitted from the cultural canon. Why should these specific works by Degas or Warhol or Vermeer be so celebrated, so singularly highlighted? This digitisation and the general accelerationism induced by COVID only exacerbates this problem. If I have access to all this art but no guidance, no structure to appreciating it, then I'm just going to look at the artists I'm aware of and look at their work, like those who enter the Louvre and beeline it to the Mona Lisa. In most cases these people don't care about the context of the work, just that they saw it. Perhaps this isn't intrinsically wrong, but it is certainly a vapid means of consumption, focusing on clout over appreciation.

When restrictions did ease up in the second-half of 2020, the spaces which were available for much of the world were more open environs where physical distancing was easy and air circulation was better. It was about this time that 'immersive exhibits' exploded in cities across North America and Europe. Largely hosted in industrial spaces, these shows permitted distancing through projections of works onto the walls of a space, creating an 'immersive experience' by having attendees be subsumed by an artwork or its constituent components. There's an argument to be made that 2020's Netflix series Emily in Paris aided the exponential growth of these shows as a consequence of the Netflix Effect, but even with this as a contributing factors, the omnipresence of these exhibits seems inexplicable.³ Nonetheless, the directors of these shows and artist foundations have claimed that this maximal approach to the works of Vincent van Gogh in particular assist in understanding the artist on a more personal level, as if viewers will see the world as the artist did, will understand the machinations of their mind prior to their death.⁴ Even ignoring the fact that this is an impossibility, to understand the lived experience of another, this perpetuates the masturbatory romanticisation of the tortured 'other,' without engaging with their purported experience in a critical manner. This ballooning of the work may induce a sense of being 'inside' the painting, but it also means turning the work of an artist known for their impasto and its consequent three-dimensionality into a flat image. Beyond this, the poor quality of a projected image in relation to a physical work means those brushstrokes won't even appear on the walls of a space, just as they won't on the screen of a phone.⁵ My problem with these exhibits is not with idea of simulacra of the works themselves, but with this glorified and yet dehumanised reproduction, claiming to be focused on the personal history of the work while losing the humanity and physical deliberation of the paintings' creation. The immersive experience has nothing to do with the works themselves, but with the idea of the work, allowing us to say we were there rather than we saw.⁶ And in the wake of the success and proliferation of these van Gogh shows, we are now inundated with these $50 multi-sensory experiences for Klimt, for Monet, for Chagall, for Picasso, for Tutankhamen, for Frida Kahlo (who I'm sure would have loved the commodification of her work for vapid consumption by white people). The presence of pre-recorded vague statements and the wafting stench of cypress brings as much to the experience of viewing these low quality images as South Park: The Fractured But Whole's promotion stunt the Nosulus Rift did by letting you smell farts. These shows claim to complement the physical gallery experience but they merely detract. What impetus is there to gaze upon a work in person when influencers claim this is superior to the rinky-dink painting, when one can state with the authentic belief that they have already seen it, when you can go do yoga in a painting!?⁷

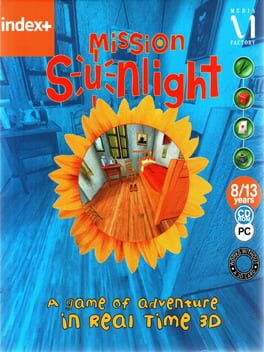

With it made abundantly clear now how much I detest the idea of the immersive experience, it must come as surprising that I was rather taken by this low-tech educational multimedia game from 1998 of all things. If the immersive exhibit is something I consider almost infantilising, how could this fare better? What Mission Sunlight has going for it immediately is that it isn't trying to pass itself off as some truest means of taking in van Gogh's work. The intro cinematic makes it evident that this is not the world of van Gogh, but some dystopic strangereal where the sun has gone out, taking with it the colour of the artist's paintings.

Our first interaction is with an on-the-fritz robot who gives us a magical star and makes it abundantly clear that despite his algorithmic attempts at restoring the paintings, he crucially has never been able to see the paintings up close. When we inspect the sprite of Fourteen Sunflowers in a Vase, we are welcomed by a polygonal representation of the artist himself. Rather than be some depressed bastardisation of our posthumous reinterpretation of van Gogh, this avatar is almost chipper in his sun hat. He invites us to use the magnifying class button, and when we do we get an incredibly close-up look at the painting and the brushstrokes on the canvas. A 115MB title from two decades past renders this human aspect more concrete than the supposed technological marvels of our present day can. Furthermore, you can click another button to have van Gogh hold up the painting so you can understand its scale.

Walking through the exhibit space, not only are the walls a disgusting hue of dentist-office beige, but they are dirty and in disrepair. The paintings are grey-scale, and even the vases which should be abound with almond blossoms are little more than collections of gnarled branches. Clicking on these paintings transports the player 'into' them, and here they are shown in colour. The subject matter is therein rendered three-dimensional and the player can move their perspective to see beyond the confines of the painting. What is particularly endearing about this is how the dithered textures impart a quasi-Impressionist feel despite being a limitation of technology. Instead of hearing lilting violins, the soundscape is realistic. Roosters crow, the wind blows, leaves tumble to the ground. In each painting you need to find an object to restore the colour, and certain interactables help you proceed. For Cottage with Decrepit Barn and Stooping Woman, one can actually enter the slanted building only for the interior to be the selfsame from The Potato Eaters, with the table embodying Still Life with an Earthen Bowl with Potatoes. Obviously some liberties have been taken in order to create these more singular, cohesive spaces, but it helps to demonstrate that these paintings were not created in a vacuum, and in fact were inspired by similar, if not identical, settings. These early works are of the same earthen hues in game as they are in reality, contrasted against a gorgeous blue sky.

Finding a potato for Still Life with an Earthen Bowl with Potatoes bestows upon us an educational tidbit of context, that still life paintings are historically flowing with finest dining ware and ostentatious displays of food, representing wealth and bounty. We swirl around Jan Davidszoon de Heem's Still-Life with Fruit and Lobster before van Gogh tells us his desire to show the food of the poor and demonstrate this connection between dining ware from the earth, and tubers from the earth in a display of realist honesty. Restoring The Potato Eaters tells us that it is difficult to break with what you have been told to do. Though this is obviously in response to academic traditions as taught to classically trained artists at Paris' École des Beaux-Arts, it resonates with me because of those immersive experiences. In a sense, those exhibits have broken with the expected, but they have also perpetuated that consumptive mode which snaps a picture and moves on, akin to an Instagram trap. In Mission Sunlight, the tradition of the art gallery has been eschewed for a different maximal approach which at times demonstrates a falsehood about these works through the artistic liberties of an imagined 3D space, but by also teaching directly without shoving contexts onto a placard, a catalogue, or an art history education. Maybe this gamification of art is itself problematic too, but as an edutainment piece of software I am more forgiving.

When we venture into The Night Cafe, I am apprehensive because of my time with 2016's The Night Cafe: A VR Tribute to Van Gogh. That grotesquerie attempted to bring multiple works into one space in a manner I would consider a failure, those other works managing to detract from titular cafe. The scale of the people made it especially hard to immerse myself in, but thankfully Mission Sunlight opted to remove those figures entirely. The geometries here are simpler and more angular, but it weirdly works. Instead of the yellow smears of smooth brushwork in A VR Tribute coming off the lamps, Mission Sunlight's lamps take the actual brushwork of The Night Cafe and turn them into quasi-3D sprites, like a tree in Super Mario 64 to much greater effect. A VR Tribute is a strangely disconnected sensory experience. Mission Sunlight inundates the player with the din of cafe culture, clocks ticking away incessantly, indistinct conversation washing over us.

The later part of van Gogh's life is, understandably, much less depressing here than in reality. Stepping into the Hospital at Arles series, we can hear the anguished cries of the patients who are again not depicted, but the commentary avoids sounding downtrodden. Van Gogh himself speaks of the proliferation of Japanese art and Japonisme when we restore Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, rather than wallow in misery. Ward in the Hospital in Arles' commentary touches on the unappreciative response to his art, but again it isn't masturbatory, but informative. We see van Gogh not as a man defined by mental illness, but simply as a man who wished to paint. Though this is painting too simple of a portrait in many ways, it also helpfully avoids the pratfalls of the contemporary imagining of van Gogh.

Mission Sunlight warms the cockles of my heart in a way I didn't expect it to at all. It is simply a good piece of edutainment software which is informative in a way I wouldn't expect of a children's approach to art history. It is refreshing and truthfully immersive in rendering paintings as physical spaces, rather than as flat images on a wall. It evokes an honesty to the painted work that is astounding for 1998, and serves as a phenomenal alternative to AR experiences or digital catalogues. This is a work which expects willful engagement, and rewards it handsomely. I wholeheartedly recommend downloading a copy and running this in a VM if you have the slightest interest in art history.

1. Alexander Panetta, “A World of Art at Our Fingertips: How Covid-19 Accelerated the Digitization of Culture | CBC News,” CBCnews (CBC/Radio Canada, May 8, 2021), https://www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/digitization-culture-pandemic-1.6015861.

2. “Show Me the Monet - Google Arts & Culture,” Google (Google), accessed September 3, 2022, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/yAUh79Qtnpb8bA.

3. Brian Boucher, “'Emily in Paris' Fueled a Frenzy for Immersive Van Gogh 'Experiences.' Now a Consumer Watchdog Is Issuing a Warning about NYC's Dueling Shows,” Artnet News, March 16, 2021, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/immersive-van-gogh-better-business-bureau-1951887.

4. Christina Morales, “Immersive Van Gogh Experiences Bloom like Sunflowers,” The New York Times (The New York Times, March 7, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/07/arts/design/van-gogh-immersive-experiences.html.

5. Jay Pfeifer, “'Immersive Van Gogh' Has Upsides and Downsides, Explains Art Prof,” Davidson, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.davidson.edu/news/2021/04/16/immersive-van-gogh-has-upsides-and-downsides-explains-art-prof.

6. Anna Wiener, “The Rise of ‘Immersive’ Art,” The New Yorker, February 10, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-silicon-valley/the-rise-and-rise-of-immersive-art.

7. “You Can Now Practice Yoga within the Immersive Van Gogh Exhibit in San Antonio,” KSAT (KSAT San Antonio, August 12, 2022), https://www.ksat.com/news/local/2022/08/12/you-can-now-practice-yoga-within-the-immersive-van-gogh-exhibit-in-san-antonio/.

When restrictions did ease up in the second-half of 2020, the spaces which were available for much of the world were more open environs where physical distancing was easy and air circulation was better. It was about this time that 'immersive exhibits' exploded in cities across North America and Europe. Largely hosted in industrial spaces, these shows permitted distancing through projections of works onto the walls of a space, creating an 'immersive experience' by having attendees be subsumed by an artwork or its constituent components. There's an argument to be made that 2020's Netflix series Emily in Paris aided the exponential growth of these shows as a consequence of the Netflix Effect, but even with this as a contributing factors, the omnipresence of these exhibits seems inexplicable.³ Nonetheless, the directors of these shows and artist foundations have claimed that this maximal approach to the works of Vincent van Gogh in particular assist in understanding the artist on a more personal level, as if viewers will see the world as the artist did, will understand the machinations of their mind prior to their death.⁴ Even ignoring the fact that this is an impossibility, to understand the lived experience of another, this perpetuates the masturbatory romanticisation of the tortured 'other,' without engaging with their purported experience in a critical manner. This ballooning of the work may induce a sense of being 'inside' the painting, but it also means turning the work of an artist known for their impasto and its consequent three-dimensionality into a flat image. Beyond this, the poor quality of a projected image in relation to a physical work means those brushstrokes won't even appear on the walls of a space, just as they won't on the screen of a phone.⁵ My problem with these exhibits is not with idea of simulacra of the works themselves, but with this glorified and yet dehumanised reproduction, claiming to be focused on the personal history of the work while losing the humanity and physical deliberation of the paintings' creation. The immersive experience has nothing to do with the works themselves, but with the idea of the work, allowing us to say we were there rather than we saw.⁶ And in the wake of the success and proliferation of these van Gogh shows, we are now inundated with these $50 multi-sensory experiences for Klimt, for Monet, for Chagall, for Picasso, for Tutankhamen, for Frida Kahlo (who I'm sure would have loved the commodification of her work for vapid consumption by white people). The presence of pre-recorded vague statements and the wafting stench of cypress brings as much to the experience of viewing these low quality images as South Park: The Fractured But Whole's promotion stunt the Nosulus Rift did by letting you smell farts. These shows claim to complement the physical gallery experience but they merely detract. What impetus is there to gaze upon a work in person when influencers claim this is superior to the rinky-dink painting, when one can state with the authentic belief that they have already seen it, when you can go do yoga in a painting!?⁷

With it made abundantly clear now how much I detest the idea of the immersive experience, it must come as surprising that I was rather taken by this low-tech educational multimedia game from 1998 of all things. If the immersive exhibit is something I consider almost infantilising, how could this fare better? What Mission Sunlight has going for it immediately is that it isn't trying to pass itself off as some truest means of taking in van Gogh's work. The intro cinematic makes it evident that this is not the world of van Gogh, but some dystopic strangereal where the sun has gone out, taking with it the colour of the artist's paintings.

Our first interaction is with an on-the-fritz robot who gives us a magical star and makes it abundantly clear that despite his algorithmic attempts at restoring the paintings, he crucially has never been able to see the paintings up close. When we inspect the sprite of Fourteen Sunflowers in a Vase, we are welcomed by a polygonal representation of the artist himself. Rather than be some depressed bastardisation of our posthumous reinterpretation of van Gogh, this avatar is almost chipper in his sun hat. He invites us to use the magnifying class button, and when we do we get an incredibly close-up look at the painting and the brushstrokes on the canvas. A 115MB title from two decades past renders this human aspect more concrete than the supposed technological marvels of our present day can. Furthermore, you can click another button to have van Gogh hold up the painting so you can understand its scale.

Walking through the exhibit space, not only are the walls a disgusting hue of dentist-office beige, but they are dirty and in disrepair. The paintings are grey-scale, and even the vases which should be abound with almond blossoms are little more than collections of gnarled branches. Clicking on these paintings transports the player 'into' them, and here they are shown in colour. The subject matter is therein rendered three-dimensional and the player can move their perspective to see beyond the confines of the painting. What is particularly endearing about this is how the dithered textures impart a quasi-Impressionist feel despite being a limitation of technology. Instead of hearing lilting violins, the soundscape is realistic. Roosters crow, the wind blows, leaves tumble to the ground. In each painting you need to find an object to restore the colour, and certain interactables help you proceed. For Cottage with Decrepit Barn and Stooping Woman, one can actually enter the slanted building only for the interior to be the selfsame from The Potato Eaters, with the table embodying Still Life with an Earthen Bowl with Potatoes. Obviously some liberties have been taken in order to create these more singular, cohesive spaces, but it helps to demonstrate that these paintings were not created in a vacuum, and in fact were inspired by similar, if not identical, settings. These early works are of the same earthen hues in game as they are in reality, contrasted against a gorgeous blue sky.

Finding a potato for Still Life with an Earthen Bowl with Potatoes bestows upon us an educational tidbit of context, that still life paintings are historically flowing with finest dining ware and ostentatious displays of food, representing wealth and bounty. We swirl around Jan Davidszoon de Heem's Still-Life with Fruit and Lobster before van Gogh tells us his desire to show the food of the poor and demonstrate this connection between dining ware from the earth, and tubers from the earth in a display of realist honesty. Restoring The Potato Eaters tells us that it is difficult to break with what you have been told to do. Though this is obviously in response to academic traditions as taught to classically trained artists at Paris' École des Beaux-Arts, it resonates with me because of those immersive experiences. In a sense, those exhibits have broken with the expected, but they have also perpetuated that consumptive mode which snaps a picture and moves on, akin to an Instagram trap. In Mission Sunlight, the tradition of the art gallery has been eschewed for a different maximal approach which at times demonstrates a falsehood about these works through the artistic liberties of an imagined 3D space, but by also teaching directly without shoving contexts onto a placard, a catalogue, or an art history education. Maybe this gamification of art is itself problematic too, but as an edutainment piece of software I am more forgiving.

When we venture into The Night Cafe, I am apprehensive because of my time with 2016's The Night Cafe: A VR Tribute to Van Gogh. That grotesquerie attempted to bring multiple works into one space in a manner I would consider a failure, those other works managing to detract from titular cafe. The scale of the people made it especially hard to immerse myself in, but thankfully Mission Sunlight opted to remove those figures entirely. The geometries here are simpler and more angular, but it weirdly works. Instead of the yellow smears of smooth brushwork in A VR Tribute coming off the lamps, Mission Sunlight's lamps take the actual brushwork of The Night Cafe and turn them into quasi-3D sprites, like a tree in Super Mario 64 to much greater effect. A VR Tribute is a strangely disconnected sensory experience. Mission Sunlight inundates the player with the din of cafe culture, clocks ticking away incessantly, indistinct conversation washing over us.

The later part of van Gogh's life is, understandably, much less depressing here than in reality. Stepping into the Hospital at Arles series, we can hear the anguished cries of the patients who are again not depicted, but the commentary avoids sounding downtrodden. Van Gogh himself speaks of the proliferation of Japanese art and Japonisme when we restore Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, rather than wallow in misery. Ward in the Hospital in Arles' commentary touches on the unappreciative response to his art, but again it isn't masturbatory, but informative. We see van Gogh not as a man defined by mental illness, but simply as a man who wished to paint. Though this is painting too simple of a portrait in many ways, it also helpfully avoids the pratfalls of the contemporary imagining of van Gogh.

Mission Sunlight warms the cockles of my heart in a way I didn't expect it to at all. It is simply a good piece of edutainment software which is informative in a way I wouldn't expect of a children's approach to art history. It is refreshing and truthfully immersive in rendering paintings as physical spaces, rather than as flat images on a wall. It evokes an honesty to the painted work that is astounding for 1998, and serves as a phenomenal alternative to AR experiences or digital catalogues. This is a work which expects willful engagement, and rewards it handsomely. I wholeheartedly recommend downloading a copy and running this in a VM if you have the slightest interest in art history.

1. Alexander Panetta, “A World of Art at Our Fingertips: How Covid-19 Accelerated the Digitization of Culture | CBC News,” CBCnews (CBC/Radio Canada, May 8, 2021), https://www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/digitization-culture-pandemic-1.6015861.

2. “Show Me the Monet - Google Arts & Culture,” Google (Google), accessed September 3, 2022, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/yAUh79Qtnpb8bA.

3. Brian Boucher, “'Emily in Paris' Fueled a Frenzy for Immersive Van Gogh 'Experiences.' Now a Consumer Watchdog Is Issuing a Warning about NYC's Dueling Shows,” Artnet News, March 16, 2021, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/immersive-van-gogh-better-business-bureau-1951887.

4. Christina Morales, “Immersive Van Gogh Experiences Bloom like Sunflowers,” The New York Times (The New York Times, March 7, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/07/arts/design/van-gogh-immersive-experiences.html.

5. Jay Pfeifer, “'Immersive Van Gogh' Has Upsides and Downsides, Explains Art Prof,” Davidson, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.davidson.edu/news/2021/04/16/immersive-van-gogh-has-upsides-and-downsides-explains-art-prof.

6. Anna Wiener, “The Rise of ‘Immersive’ Art,” The New Yorker, February 10, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-silicon-valley/the-rise-and-rise-of-immersive-art.

7. “You Can Now Practice Yoga within the Immersive Van Gogh Exhibit in San Antonio,” KSAT (KSAT San Antonio, August 12, 2022), https://www.ksat.com/news/local/2022/08/12/you-can-now-practice-yoga-within-the-immersive-van-gogh-exhibit-in-san-antonio/.

Detchibe

3 months ago