This review contains spoilers

Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance wasn’t any better received than Circle of the Moon was. The second entry in a series of Castlevania games on Nintendo’s horizontal handheld system was released only a mere year after Konami decided to showcase it with a title that would stamp the Metroidvania direction that Symphony of the Night established for the series in permanent ink. While this is technically the case, upon playing Circle of the Moon, could the game really be defined as either a sequel or a spiritual successor to one of the franchise's most celebrated and influential titles? Argue about its subjective quality all you want, but what I’m prodding at is that Circle of the Moon did not want to walk in Symphony’s shadow. It’s readily apparent by the grittier visuals, the return of the whip and secondary items, and the brutally uncompromising difficulty that Circle of the Moon sought to pave its own path while the trail was admittedly on the same Metroidvania ground that Symphony had cemented. Because Circle of the Moon was radically different from the game that was advertised, it did not sit well with the new audience that Symphony garnered. Personally, I thought the deviations from the Symphony were refreshing, but I understand why someone who was introduced to the series with a game that featured multiple weapons, grandiose graphics, and a more manageable difficulty curve would be turned off by Circle of the Moon’s repressive minimalism. Because the response from Circle of the Moon was generally lackluster, the next entry on the GBA served as an opportunity to rectify the failed experimentation and craft something more likened to Symphony of the Night. Despite their best efforts to appease Symphony of the Night enthusiasts, the oxymoronically-titled Harmony of Dissonance still didn’t satisfy them, and here is why.

We’ve reverted back to one previous century for Harmony of Dissonance when the Belmonts were still relevant, for yet another member of the iconic vampire killing clan is introduced as our protagonist: Juste Belmont. Juste’s childhood friend Lydie has been kidnapped and taken to a strange castle that has been erected on the grassy hills of whatever European village this is seemingly overnight. Upon exploring the foyer of this estate, good ol’ series staple Death confirms that the castle is indeed another one of Dracula’s new constructions (no shit). Juste splits the task of rescuing Lydie with his other lifelong best friend Maxim, who is suffering from amnesia and can’t remember what his objective was beforehand. Even though Juste has no canonical relation to Nathan Graves, apparently what binds them together as the protagonists of GBA Castlevania games is performing the grunt work of traversing through Dracula’s castle with a friend to save someone dear to them from Dracula’s clutches. Boy, I sure do hope Maxim isn’t seduced by the darkness of Dracula as easily as Hugh was (fingers crossed).

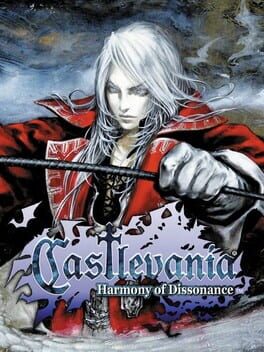

The predominant complaint that most people seem to have regarding Harmony of Dissonance is with its presentation. It proves to me that Circle of the Moon was artistically restrained as opposed to mechanically and that the GBA was capable of rendering striking visuals. Still, considering Harmony of Dissonance’s aim was to make a mobile Symphony of the Night, their futile efforts to transport its glorious, refined pixel art to a 2.9-inch screen was interesting, to say the least. Harmony of Dissonance displays the most striking visuals ever seen across any Castlevania title. Its graphics don’t simply pop out with buoyant flair: they scream at the player with the subtlety of a wild howler monkey. The word “lurid” doesn’t even quite cut it. In their attempt to emulate the splendor of Symphony on a mechanically inferior piece of hardware, Konami has managed to craft what playing Symphony on acid would be like. Not a single piece of the background or foreground isn’t psychedelic, exhibiting that fleshy GBA color palette seen in Metroid Fusion only amped up to eleven on the intensity scale. Some of the backgrounds across the castle are simply kaleidoscopic views made to simulate the apex of drug-addled freakouts. Still, the player will have to make a concerted effort to peek over at the backdrops because I don’t know how one can keep their eyes off of Juste’s cloak which is so crimson red that it’s practically bleeding. There’s bombast, and then there is a complete overload of visual flair to the point of being stomach-churning, which is how many of the detractors describe how the game’s visuals upset them. It doesn’t help that the sound design is irritatingly shrill as well, really honing in on the hallucinatory feeling. Personally, Harmony of Dissonance’s presentation is its strongest aspect. The mix of the dazzling and the macabre reminds me of Giallo, an Italian subgenre of horror films whose refusal to color in the lines is its defining idiosyncrasy. As for the piercing sound design, I don’t think that was intentional, so there’s one legitimate demerit I’m going to have to mark off Harmony of Dissonance for.

Another criticism of Harmony of Dissonance I have that doesn’t seem to be as widely discussed is its protagonist. Besides his stupid, awkward name that is hard to pronounce, Juste Belmont is an imposter. How can Konami peacefully sleep at night after such brazen lies trying to convince all of us that this man isn’t a vampire? His pale, bedsheet-white skin complexion makes Alucard look Sudanese by comparison, and Alucard has never been one to shy away from revealing his vampiric form. Alucard is so white that Aryans would worship him as their Messiah. I feel that if I stabbed Juste, a translucent green goo would spill from his insides instead of the warm, organic red blood that signifies a mortal, earthly creature. On top of looking like an undead creature of the night, Juste also moves like one as well. Whenever Juste jumps as par for the course in a platformer game, his brief ascent is strangely languid, as if he’s manipulating the gravity used to bounce himself upward like oh, I don’t know, a vampire would. See the playground scene from Let the Right One In where the vampire girl hops off the equipment for reference. Juste’s less grounded movement is also annoyingly imprecise, making the player correct for the unnatural physics of a character that is supposed to be human. He does perfect the dash maneuver that Alucard introduced in Symphony to expertise, darting around every room of the castle like he’s a poncy Sonic the Hedgehog. Still, I must impress that Juste beats Alucard, who is a fucking vampire, with his proficiency in executing this supernatural move. Sorry to say Simon, but someone has spiked your gene pool with the blood of your enemies. I don’t like Juste’s jerkoff name, I don’t like his jerkoff face, and I don’t like the jerkoff way he carries himself on the field.

The only Belmont signifier that Juste possesses that proves his kinship is using the family standard weapon of the whip along with the collective of secondary weapons that use ammunition we’ve been familiar with since the days of Simon on the NES. Even though Juste’s physicality is meant to ape Alucard, at least he retains the classic Castlevania in a Metroidvania environment like Circle of the Moon started to do. Harmony of Dissonance also repeats the use of deadly, screen-encompassing spells transferred over to the GBA from Rondo of Blood, which is always a neat way to quickly annihilate all enemies. While I appreciate how the essentials of Castlevania’s gameplay are preserved nicely, what innovations does Harmony of Dissonance contribute to the Castlevania formula to discern itself among the pack? Harmony of Dissonance seems to emphasize clothing and items as integral mechanics. Circle of the Moon didn’t skip using collectible wear coinciding with RPG attributes, but Harmony of Dissonance adds another layer of interactivity to them besides their offensive and defensive perks. All of the major collectibles needed to progress through the game in Harmony of Dissonance are intertwined with the items of clothing that Juste picks up around the corridors of Dracula’s castle. Alternate flails for the whip are also strewn about in the same obscured settings, and a few are necessary to use to bypass obstacles around the estate. Implementing the progression items into the slew of varied clothing is bound to confuse most veterans of the series, for it's unclear when they unlock what is needed to progress. Usually, an important item is obtained after defeating a boss, signifying a stepping stone in progress with a substantial accomplishment. The player can determine which item they should use by reading its description in the menu, but how are they to know which one has a special attribute among the mishmash of clothing items, which are also scrambled in the menu with no organization to speak of? Also, it’s incredibly inconvenient changing from a clothing item with better stats back to the less-than-deal one to use once in a blue moon to unlock a passageway.

What is ten times more messy and disorganized in Harmony of Dissonance is the game’s interpretation of Symphony’s second half. Once Juste finds himself on the opposite side of Dracula’s castle, Death’s second wave of exposition involves explaining to Juste that Maxim has unfortunately fallen to the entrancing gaze of Dracula. Apparently, the evil aura exuding from the force of all six of Dracula’s body parts has caused a schism in Maxim’s body and mind, and the anti-Maxim created from the rupturing is the one who captured Lydie in the first place. Another grand effect of Maxim toying with Dracula’s remains is that it has caused a mirrored version of the castle to materialize in another dimension, which is where Lydie is being held captive and Dracula’s assorted parts are still radiating pure malevolence. Already, the premise of how the game’s second half came to be is a head-scratcher, but wait until it’s time to enter the opposing realm and interact with it. Instead of teleporting Juste around the castle, the warp gates that are marked with a yellow square on the map will transport Juste to Maxim’s fabricated castle, which is referred to as “Castle B.” No, the castle is not twisted on its head (which would be especially nauseating in this game), but an uncanny version of the same castle with slightly tougher enemies. Actually, there really isn’t all that much difference in the design except for the most minute rearrangements that usually lead to pertinent points of progress. What “Castle B” mostly achieves is confusing the hell out of the player. Upon warping to “Castle B” for the first time, the western half of the castle is blocked off now because the shift has torn the entire castle asunder like Germany after WWII. Juste is confined to one fraction of the castle for quite a while, and there doesn’t seem to be a clear exit because this is also when all pathways to progress become hazy and circuitous. Basically, an impediment found in one dimension can possibly be dealt with in the other, which involves several back-and-forth treks to and from the warp gate. The slog of unclear progression in the fake castle is enough to give someone a headache.

I suppose the befuddling frustration I experienced upon entering Maxim’s “alternate” realm of existence was the only thing keeping me from breezing through Harmony of Dissonance. Fans of the classic Castlevania titles complained that Symphony of the Night was too easy, but only compared to the blisteringly painful difficulty curves found in the traditional 2D platformers that gave players an exhilarating rush of accomplishment. Harmony of Dissonance, on the other hand, is easy by the general standards across all video games. One could give it to a small child as an introductory peek into the series, and I doubt they’d have much trouble with it until the dimensional flip-flopping takes place. Potions of varying regenerative amounts will drop from enemies fairly often, and the roast found in the cracked corners of the walls has been shifted into turkey and turkey legs to itemize the healing properties of food in varying quantities. Overall enemy damage is tepid enough, but all of the game’s bosses are laughably pitiful when they keep insisting on repeating the same languid tactics that I already evaded seconds in advance. A healing orb drops after defeating each boss similar to the classic titles but unlike those grueling tests of skill, the damage these pathetic bosses dished out barely amounted to a scratch, the plethora of healing items withstanding. I’ve made positive claims for all previous Castlevania games that were deemed easy before, but Harmony of Dissonance’s borderline effortlessness is enough to make me resign from my defendant post.

The primary objective in “Castle B” is finishing what Maxim started by reobtaining all six pieces of Dracula scattered across the "Twilight Zone" of his castle. Doing so will unfasten a mechanical door situated below the floor leading to the underground chamber at the center of the gothic architecture where an unconscious Lydie is stashed. Because I played Symphony and know that this game is doing its damndest to ape it, I knew there would be additional requirements to fight Dracula that the game wasn’t going to inform me of. Upon performing extraneous research, the caveats to facing Dracula once again were to wear both rings representing the two friends of Juste upon entering the boss arena and arriving here from the alternate castle. Juste will first subdue his corrupted male friend before the dark lord erupts from Maxim into the shape of something so hideous and malformed that it would make David Cronenberg say, “What the fuck?” In the optimal ending, Juste escapes the crumbling manor with Maxim and Lydie. Lydie is fine, but it’s implied that the evil form of Maxim bit her on the neck, which would mean that this happy ending carries complications. However, even a Maxim possessed by Dracula was never a vampire, so all that might occur is him getting slapped with a sexual assault charge at most. Considering that I barely broke a sweat fighting Maxim and Dracula back to back and I don’t care for these characters, I don’t think it was worth the additional effort beforehand to ensure the best outcome.

What Circle of the Moon expertly avoided in translating Symphony’s Metroidvania design to a handheld system was distancing itself as a prospective “Symphony on the go”. I think it’s obvious that a system that primarily plays 2D games would serve as a perfect hub for the Metroidvania genre, but Symphony made such a colossal impact that it set such a high standard that the GBA couldn’t compete with. Harmony of Dissonance is the result of acceding to everyone who did not appreciate Circle of the Moon’s maverick decisions by coming as close to Symphony of the Night as feasibly possible, and apparently, only I had the foresight to know this wouldn’t work. It actually amends every problem across Circle of the Moon, but it’s when it tries to differentiate itself from Symphony while also tracing Symphony’s template where the game falls flat. Symphony’s graphics were exuberant, so Harmony’s attempt resulted in an acid-laced attack on the senses. Symphony’s difficulty was more manageable than any classic Castlevania title, so Harmony dumbed itself down even further to the point of being braindead. Symphony’s reversed castle section fundamentally worked to pad the game, so Harmony’s version of this without outright copying it amounted to a roundabout disaster. Any game that dips back into an idea from Simon’s Quest is desperate to discern itself from the pack, which is really what the developers should’ve focused on again instead of the fool’s errand that fueled Harmony’s development. Besides the eye-popping visuals, there isn’t much to recommend regarding Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance.

------

Attribution: https://erockreviews.blogspot.com

We’ve reverted back to one previous century for Harmony of Dissonance when the Belmonts were still relevant, for yet another member of the iconic vampire killing clan is introduced as our protagonist: Juste Belmont. Juste’s childhood friend Lydie has been kidnapped and taken to a strange castle that has been erected on the grassy hills of whatever European village this is seemingly overnight. Upon exploring the foyer of this estate, good ol’ series staple Death confirms that the castle is indeed another one of Dracula’s new constructions (no shit). Juste splits the task of rescuing Lydie with his other lifelong best friend Maxim, who is suffering from amnesia and can’t remember what his objective was beforehand. Even though Juste has no canonical relation to Nathan Graves, apparently what binds them together as the protagonists of GBA Castlevania games is performing the grunt work of traversing through Dracula’s castle with a friend to save someone dear to them from Dracula’s clutches. Boy, I sure do hope Maxim isn’t seduced by the darkness of Dracula as easily as Hugh was (fingers crossed).

The predominant complaint that most people seem to have regarding Harmony of Dissonance is with its presentation. It proves to me that Circle of the Moon was artistically restrained as opposed to mechanically and that the GBA was capable of rendering striking visuals. Still, considering Harmony of Dissonance’s aim was to make a mobile Symphony of the Night, their futile efforts to transport its glorious, refined pixel art to a 2.9-inch screen was interesting, to say the least. Harmony of Dissonance displays the most striking visuals ever seen across any Castlevania title. Its graphics don’t simply pop out with buoyant flair: they scream at the player with the subtlety of a wild howler monkey. The word “lurid” doesn’t even quite cut it. In their attempt to emulate the splendor of Symphony on a mechanically inferior piece of hardware, Konami has managed to craft what playing Symphony on acid would be like. Not a single piece of the background or foreground isn’t psychedelic, exhibiting that fleshy GBA color palette seen in Metroid Fusion only amped up to eleven on the intensity scale. Some of the backgrounds across the castle are simply kaleidoscopic views made to simulate the apex of drug-addled freakouts. Still, the player will have to make a concerted effort to peek over at the backdrops because I don’t know how one can keep their eyes off of Juste’s cloak which is so crimson red that it’s practically bleeding. There’s bombast, and then there is a complete overload of visual flair to the point of being stomach-churning, which is how many of the detractors describe how the game’s visuals upset them. It doesn’t help that the sound design is irritatingly shrill as well, really honing in on the hallucinatory feeling. Personally, Harmony of Dissonance’s presentation is its strongest aspect. The mix of the dazzling and the macabre reminds me of Giallo, an Italian subgenre of horror films whose refusal to color in the lines is its defining idiosyncrasy. As for the piercing sound design, I don’t think that was intentional, so there’s one legitimate demerit I’m going to have to mark off Harmony of Dissonance for.

Another criticism of Harmony of Dissonance I have that doesn’t seem to be as widely discussed is its protagonist. Besides his stupid, awkward name that is hard to pronounce, Juste Belmont is an imposter. How can Konami peacefully sleep at night after such brazen lies trying to convince all of us that this man isn’t a vampire? His pale, bedsheet-white skin complexion makes Alucard look Sudanese by comparison, and Alucard has never been one to shy away from revealing his vampiric form. Alucard is so white that Aryans would worship him as their Messiah. I feel that if I stabbed Juste, a translucent green goo would spill from his insides instead of the warm, organic red blood that signifies a mortal, earthly creature. On top of looking like an undead creature of the night, Juste also moves like one as well. Whenever Juste jumps as par for the course in a platformer game, his brief ascent is strangely languid, as if he’s manipulating the gravity used to bounce himself upward like oh, I don’t know, a vampire would. See the playground scene from Let the Right One In where the vampire girl hops off the equipment for reference. Juste’s less grounded movement is also annoyingly imprecise, making the player correct for the unnatural physics of a character that is supposed to be human. He does perfect the dash maneuver that Alucard introduced in Symphony to expertise, darting around every room of the castle like he’s a poncy Sonic the Hedgehog. Still, I must impress that Juste beats Alucard, who is a fucking vampire, with his proficiency in executing this supernatural move. Sorry to say Simon, but someone has spiked your gene pool with the blood of your enemies. I don’t like Juste’s jerkoff name, I don’t like his jerkoff face, and I don’t like the jerkoff way he carries himself on the field.

The only Belmont signifier that Juste possesses that proves his kinship is using the family standard weapon of the whip along with the collective of secondary weapons that use ammunition we’ve been familiar with since the days of Simon on the NES. Even though Juste’s physicality is meant to ape Alucard, at least he retains the classic Castlevania in a Metroidvania environment like Circle of the Moon started to do. Harmony of Dissonance also repeats the use of deadly, screen-encompassing spells transferred over to the GBA from Rondo of Blood, which is always a neat way to quickly annihilate all enemies. While I appreciate how the essentials of Castlevania’s gameplay are preserved nicely, what innovations does Harmony of Dissonance contribute to the Castlevania formula to discern itself among the pack? Harmony of Dissonance seems to emphasize clothing and items as integral mechanics. Circle of the Moon didn’t skip using collectible wear coinciding with RPG attributes, but Harmony of Dissonance adds another layer of interactivity to them besides their offensive and defensive perks. All of the major collectibles needed to progress through the game in Harmony of Dissonance are intertwined with the items of clothing that Juste picks up around the corridors of Dracula’s castle. Alternate flails for the whip are also strewn about in the same obscured settings, and a few are necessary to use to bypass obstacles around the estate. Implementing the progression items into the slew of varied clothing is bound to confuse most veterans of the series, for it's unclear when they unlock what is needed to progress. Usually, an important item is obtained after defeating a boss, signifying a stepping stone in progress with a substantial accomplishment. The player can determine which item they should use by reading its description in the menu, but how are they to know which one has a special attribute among the mishmash of clothing items, which are also scrambled in the menu with no organization to speak of? Also, it’s incredibly inconvenient changing from a clothing item with better stats back to the less-than-deal one to use once in a blue moon to unlock a passageway.

What is ten times more messy and disorganized in Harmony of Dissonance is the game’s interpretation of Symphony’s second half. Once Juste finds himself on the opposite side of Dracula’s castle, Death’s second wave of exposition involves explaining to Juste that Maxim has unfortunately fallen to the entrancing gaze of Dracula. Apparently, the evil aura exuding from the force of all six of Dracula’s body parts has caused a schism in Maxim’s body and mind, and the anti-Maxim created from the rupturing is the one who captured Lydie in the first place. Another grand effect of Maxim toying with Dracula’s remains is that it has caused a mirrored version of the castle to materialize in another dimension, which is where Lydie is being held captive and Dracula’s assorted parts are still radiating pure malevolence. Already, the premise of how the game’s second half came to be is a head-scratcher, but wait until it’s time to enter the opposing realm and interact with it. Instead of teleporting Juste around the castle, the warp gates that are marked with a yellow square on the map will transport Juste to Maxim’s fabricated castle, which is referred to as “Castle B.” No, the castle is not twisted on its head (which would be especially nauseating in this game), but an uncanny version of the same castle with slightly tougher enemies. Actually, there really isn’t all that much difference in the design except for the most minute rearrangements that usually lead to pertinent points of progress. What “Castle B” mostly achieves is confusing the hell out of the player. Upon warping to “Castle B” for the first time, the western half of the castle is blocked off now because the shift has torn the entire castle asunder like Germany after WWII. Juste is confined to one fraction of the castle for quite a while, and there doesn’t seem to be a clear exit because this is also when all pathways to progress become hazy and circuitous. Basically, an impediment found in one dimension can possibly be dealt with in the other, which involves several back-and-forth treks to and from the warp gate. The slog of unclear progression in the fake castle is enough to give someone a headache.

I suppose the befuddling frustration I experienced upon entering Maxim’s “alternate” realm of existence was the only thing keeping me from breezing through Harmony of Dissonance. Fans of the classic Castlevania titles complained that Symphony of the Night was too easy, but only compared to the blisteringly painful difficulty curves found in the traditional 2D platformers that gave players an exhilarating rush of accomplishment. Harmony of Dissonance, on the other hand, is easy by the general standards across all video games. One could give it to a small child as an introductory peek into the series, and I doubt they’d have much trouble with it until the dimensional flip-flopping takes place. Potions of varying regenerative amounts will drop from enemies fairly often, and the roast found in the cracked corners of the walls has been shifted into turkey and turkey legs to itemize the healing properties of food in varying quantities. Overall enemy damage is tepid enough, but all of the game’s bosses are laughably pitiful when they keep insisting on repeating the same languid tactics that I already evaded seconds in advance. A healing orb drops after defeating each boss similar to the classic titles but unlike those grueling tests of skill, the damage these pathetic bosses dished out barely amounted to a scratch, the plethora of healing items withstanding. I’ve made positive claims for all previous Castlevania games that were deemed easy before, but Harmony of Dissonance’s borderline effortlessness is enough to make me resign from my defendant post.

The primary objective in “Castle B” is finishing what Maxim started by reobtaining all six pieces of Dracula scattered across the "Twilight Zone" of his castle. Doing so will unfasten a mechanical door situated below the floor leading to the underground chamber at the center of the gothic architecture where an unconscious Lydie is stashed. Because I played Symphony and know that this game is doing its damndest to ape it, I knew there would be additional requirements to fight Dracula that the game wasn’t going to inform me of. Upon performing extraneous research, the caveats to facing Dracula once again were to wear both rings representing the two friends of Juste upon entering the boss arena and arriving here from the alternate castle. Juste will first subdue his corrupted male friend before the dark lord erupts from Maxim into the shape of something so hideous and malformed that it would make David Cronenberg say, “What the fuck?” In the optimal ending, Juste escapes the crumbling manor with Maxim and Lydie. Lydie is fine, but it’s implied that the evil form of Maxim bit her on the neck, which would mean that this happy ending carries complications. However, even a Maxim possessed by Dracula was never a vampire, so all that might occur is him getting slapped with a sexual assault charge at most. Considering that I barely broke a sweat fighting Maxim and Dracula back to back and I don’t care for these characters, I don’t think it was worth the additional effort beforehand to ensure the best outcome.

What Circle of the Moon expertly avoided in translating Symphony’s Metroidvania design to a handheld system was distancing itself as a prospective “Symphony on the go”. I think it’s obvious that a system that primarily plays 2D games would serve as a perfect hub for the Metroidvania genre, but Symphony made such a colossal impact that it set such a high standard that the GBA couldn’t compete with. Harmony of Dissonance is the result of acceding to everyone who did not appreciate Circle of the Moon’s maverick decisions by coming as close to Symphony of the Night as feasibly possible, and apparently, only I had the foresight to know this wouldn’t work. It actually amends every problem across Circle of the Moon, but it’s when it tries to differentiate itself from Symphony while also tracing Symphony’s template where the game falls flat. Symphony’s graphics were exuberant, so Harmony’s attempt resulted in an acid-laced attack on the senses. Symphony’s difficulty was more manageable than any classic Castlevania title, so Harmony dumbed itself down even further to the point of being braindead. Symphony’s reversed castle section fundamentally worked to pad the game, so Harmony’s version of this without outright copying it amounted to a roundabout disaster. Any game that dips back into an idea from Simon’s Quest is desperate to discern itself from the pack, which is really what the developers should’ve focused on again instead of the fool’s errand that fueled Harmony’s development. Besides the eye-popping visuals, there isn’t much to recommend regarding Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance.

------

Attribution: https://erockreviews.blogspot.com