For those who do not care for JRPGs, the most common discrepancy these detractors detail is with the fighting system. Besides being developed by a company based in Japan, turn-based combat is the most notable idiosyncrasy of the JRPG genre. The player and their party members will stare down their enemies situated parallel to each other on a still battlefield. A menu is presented to the player to upset the scene’s inertia, usually with the option to attack, use items, or escape when the battle becomes too frantic to handle. After the player makes their selection, the opposing side gets to return the favor immediately, and the player always anticipates the inevitable damage of their retaliation with dread. JRPG nay-sayers claim that this format is an unrealistic way to simulate combat. Not in a million years would any feuding factions out for bloodshed patiently take turns on the offensive. In a way, it’s almost gentlemanly, an ironic twist on the viciousness and brutality of war. As for where I stand on this debate, I find turn-based combat invigorating. Something like carefully strategizing the next move in the heat of battle with a seemingly endless amount of time to act is something that only the gaming medium could effectively display. The turn-based system is relatively accessible for most gamers on a base level, and the defined leveling system grants the player a window of reference for how the difficulty for each scenario is scaled for their character. This aspect tends to be somewhat grind-intensive, but the state of being either overleveled or underleveled for any scenario mostly depends on the player’s skill all the same. The basic principles of turn-based combat also translate well across all JRPGs, cultivating a battle language understood among fans of the genre. While this makes the JRPG game easy to delve into after playing a handful of them, it also makes the genre feel stagnant. Twenty years after Square Enix pioneered the JRPG genre with Final Fantasy and Dragon Warrior, they decided to turn what they created on its head with The World Ends With You: one of the most subversive JRPGS seen in gaming.

High-concept premises are a requisite for the JRPG genre, almost as much as turn-based combat. Concepts involving role-playing usually entail a fantasy element to a certain degree, so why not go the distance and immerse yourself in something extraordinary? It helps that most of these games are developed in Japan, a country notable for conjuring up grandiose stories that forsake realism to the point of verging into biblically absurd territory. The World Ends With You follows suit with a creative premise whose rules exist outside the bounds of reality. Enter Neku: our youthful protagonist who skulks through the congested crossroads of an urban epicenter. His wispy presence in the crowd becomes so incorporeal to the point of being ghostly. Neku panics, but his existence is seemingly resurrected when he clenches onto a pin that mysteriously materializes in his hand. Suddenly, strange, hostile creatures appear along with ominous messages detailing that Neku has seven days to complete an unknown task. He then forms a pact with a girl named Shiki, who seems to be the only person who notices his presence. Their vague directive to complete in a week is then reduced to a mere 60 minutes, and failing to complete this task will result in “erasure,” a harrowing condemnation that Neku and Shiki most likely want to avoid. Immediately, the ambiguity of the scene combined with how urgently the game catapults the characters into the fray is a fantastic way to hook the player and make them interested in uncovering the mystery behind what is occurring.

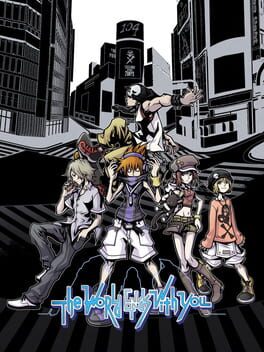

By 2007, the “domestic JRPG” that Mother and Shin Megami Tensei established to deviate from the high-fantasy tropes in genre mainstays like Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest became almost as pervasive. Out of all the JRPG games set in modern times, The World Ends With You takes the most inspiration from the Persona games. One could make this correlation due to many factors like the Shibuya setting, the teenaged characters, or the juxtaposition between the real world and the fantasy realm, otherworld thinly veiled underneath the surface. Ultimately, The World Ends With You reminds me the most of Persona because the game is oozing with style. The comic book art of The World Ends With You is the crux of the game’s presentation, with characters conversing side by side with dueling speech bubbles between them. Characters, backgrounds, and the bustling streets of Shibuya are outlined so prominently, and the stilted images of the characters move with a certain restraint during conversations and cutscenes to pronounce the graphic novel aesthetic even further. No, the game’s style isn’t ripped from Persona, but what other JRPG series possesses a kind of hip, chic presentational flair to this degree? The World Ends With You might even take its visual finesse a step beyond Persona, as every character has so much drip that they're soaked, or at least that’s how the kids these days describe it. Whether they be nameless NPCs that Neku scans, the reapers scattered around the underground, or even Neku and the rest of the players, everybody looks uniquely voguish. The collective of Shibuya looks like they traipse down the fashion runway in Milan, or maybe Shibuya is the Japanese equivalent of the extravagant Italian city (after doing some research, it is). At least one character in any Persona game is guilty of committing fashion crimes, so The World Ends With You arguably has the advantage over its stylistic inspiration for better consistency and a greater emphasis on overtly flaunting its panache.

After the opening sequence, The World Ends With You grants the player context behind what is happening to Neku and Shiki. By some circumstances, both characters have been hurled into a frantic game that takes place on the streets of Shibuya. The game exists in a subconscious realm called “the underground,” where the player can interact with civilians but not vice versa. Two players must play cooperatively, and both of them have to meet one objective under a certain time constraint. Usually, the mission entails the players arriving somewhere in Shibuya, with hooded (hoodies) pawns called Reapers impeding the player’s course to their goal. Reapers assign tasks to the players that range in objectives, and completing these tasks grants the player past the forcefield wall the Reapers erected. As tense as the beginning scene made the game out to be, the player (meaning the player of the video game in this context) can approach each day at a leisurely pace. Days usually begin with Neku and his partner at Scramble Crossing, a medium point situated appropriately between all other Shibuya districts. Sometimes, missions will be more circuitous as Neku helps reapers and citizens by finding the power source for a concert stage, finding a stolen microphone, aiding the owner of a failing ramen shop against its nearby competitor, etc. Overall, every mission presented daily in The World Ends With You is supported by exposition rather than gameplay. Running around Shibuya never grates on the player because at least the narrative always offers something interesting each day that furthers the plot. However, navigating through Tokyo’s ritzy ward is not a straightforward endeavor. Attempting to find a specific destination in Shibuya in relation to the starting point of Scramble Crossing is liable to get the player as lost as if they were hiking through the woods at night because the map of Shibuya present in the pause menu is the least reliable reference I’ve seen in a video game. The district map pinpoints the player’s location, but the surrounding areas are labeled in letter abbreviations that do not match the area's name. Earlier in the game, this isn’t so much of an issue, for the logical trajectory to the goal is to follow the reapers. Later on, when the Reapers go rogue and start attacking Neku, the game penalizes the player for retreading their steps in trying to find their destination. If I have to scour the internet for a fan-made map when the one the game provides isn’t satisfactory, something is seriously wrong.

Between walking aimlessly around Shibuya lies the real appeal of The World Ends With You: the combat. The way in which The World Ends With You innovates on typical JRPG battles is the true mark of the game’s ingenuity. Instead of swords, arrows, guns, or baseball bats, Neku is armed with an arsenal of pins. Similarly to the guns in the Persona games, the power of these seemingly innocuous pins is unlocked through the metaphysical properties of the underground. During combat, activating the pin's powers depends on its unique nature. The first combat pin given to Neku is a fire pin in which dragging the DS stylus across the screen engulfs the field in flames, damaging any enemies that come into contact. Other pins involve tapping the screen to unleash energy projectiles, locking on enemies to disperse rounds of rapid-fire bullets, summoning a line of ice pillars to stab enemies from the ground, a current that sprinkles the stage with volts of electricity, drawing an oval to send a rogue ball of energy flailing around the stage or summon boulders that careen down from the sky, etc. There is even a pin that paralyzes enemies with sonic sound waves if the player blows into the DS mic, a surefire way to make the player look like a jackass and make them weary about playing video games in public ever again. One Reaper task forces the player to equip only these pins in battle, so make sure to find sanctuary before coming across this point in the game. I’m intentionally glancing over some of the pins because the variety of different pins with different abilities is too numerous for comprehension. Neku’s pin inventory is so massive that it would make an eagle scout feel unaccomplished. Unfortunately, the amount of pins makes Neku’s inventory too congested. Purchasing pins from Shibuya’s various shops is a viable option to increase Neku’s array of weaponry, but the game will rain pins down on Neku after each battle like confetti. No matter how many of the same type Neku has, each pin is accounted for in an individual slot in the inventory. I couldn’t count how many Natural Puppy boomerang pins I had by the end of the game. Fortunately, the player can cash them out for a number of yen, and the strongest pins with a maximum experience level are listed separately. Still, the game should’ve piled the pins of the same type in one slot so the player wouldn’t have to scroll through multiple tabs. That is my sole grievance with the pin system. Otherwise, they serve as an incredibly engaging way to shake up the usual JRPG action. Mixing and matching combinations of pins guarantees that combat will never feel stale, as well as taking advantage of the unique utility of the DS and making something practical of it.

Much to Neku’s chagrin, he cannot test these weaponized pins on Shibuya’s bystanders. Enemies in The World Ends With You are referred to as “the noise,” creatures that inhabit the ethereal space of the underground. When Neku scans an area, multiple red and orange symbols are seen floating around the air like macroscopic germs. Touching one or more of these symbols will trigger a battle between potentially several different noise creatures. All the noise are a warped variation of real-life animals ranging from frogs, wolves, bats, jellyfish, kangaroos, etc. The developers even took some creative liberties with the inclusion of mythical dragons and the extinct wooly mammoth into the mix. All of the noise have a base color at their earliest encounter, but they progressively don a wide span of complexions that come with a higher difficulty level. Approaching the noise is something that the game leaves entirely in the player’s court. Unless the player is forced to face the noise for a Reaper task, they can vanquish as many of the buggers as they see fit. Tapping the various noise symbols in succession will “chain” multiple rounds with the noise, which becomes an endurance test depending on how many bouts the player willfully imposes on themselves. I recommend chaining enemies because doing so will net the player more substantial rewards. Blackish noise symbols break the rules a bit as these corrupted noises will quickly swarm the player instead of letting the player choose them. Their defense is staggeringly higher than average noise, and they insist that the player mustn't escape during battle. If combat becomes too taxing, it’s entirely the player’s fault. When the player bites off more than they can chew, the game also allows the player to restart the battle or set the difficulty to easy. I find this to be a bit patronizing, as I would rather have the option to change my selection of pins if I fail. Other than that, the game’s approach of encouraging the player to engage in combat rather than bombarding them with random encounters is quite refreshing. Plus, the noise is all as eclectic as the pins Neku uses to fight them, assuring that the player will never tire of combat due to the overall eclecticism. That, and I enjoyed seeking out new types of noise because their names listed in the compendium are all music genre related, something that tickles my music nerd fancy. “Shrew Gazer” and “Jelly Madchester” almost verge into bad pun territory, but what other video game, much less a JRPG, explicitly references these genres?

Teamwork is imperative in the game that The World Ends With You presents. The Reapers may be sadists, but even they wouldn’t leave a poor player to their own devices. A pact between Neku and Shiki is made to withstand the noise and all the other hurdles the underground might toss, which means that the player will be controlling Neku and Shiki. However, this dynamic isn’t executed like your average one-player video game team. Using the distinctive technology of the DS, the player will control Neku and Shiki simultaneously. For those of you who haven’t played this game and feel weary with this aspect in mind, I can’t blame you one bit. At least the turn-based element of normal JRPG combat involves focusing on one party member per turn. Attempting to juggle The World Ends With You’s fast-paced combat with two party members using unorthodox tools like the DS stylus may seem too overwhelming. In execution, however, the developers succeeded in making it manageable. The trick to pulling it off is making the control scheme of Neku’s partner simple. Shiki attacks in the top half of the two DS screens, sicing her animated stuffed cat on the noise with the D-Pad. Holding down the left or right tabs on the D-Pad is all the player has to do to deal sufficient damage to the noise as Shiki, and, fortunately, the duplicate noise seen on both screens is the same enemy with the same amount of health. Fusion attacks where Neku and Shiki perform a collaborative super move can be unlocked by executing different combos on the D-pad with Shiki, but I’ve found that the game grants this to the player by only mashing in one cardinal direction. After all, the developers understand that juggling two characters with two different move sets is a daunting exercise.

That is, they sympathize with the player on this front until it comes time to fight a boss. Bosses in The World Ends With You are gargantuan, heavily resistant foes whose health bars have colored layers that the player must slowly dwindle. Durability is not the issue here. The developers affirm the worries some might have had about the practicality of the game’s combat with the bosses. Frequently, Neku and his partner must take turns depleting two separate health bars, and the character who isn’t fighting the boss on their screen does not get a chance to relax as they still have to contend with smaller enemies. Either that or they must complete a portion of the fight that allows the other character to damage the boss. Neku and his partner don’t share a health bar, but if one character is beaten within an inch of their life, the other suffers by taking more damage upon being hit. I’m not entirely sure if it's due to my lack of peripheral vision, but the scatterbrained double tasking needed to defeat these bosses is unfair. Either the game could've given the player a choice to use the top screen, or co-op play should’ve been implemented.

The World Ends With You’s ambitions regarding the divergent gameplay can be questionable. However, the same cannot be said for the narrative substance that upholds it. The World Ends With You produces some of the most dynamic and nuanced characters I’ve seen in any video game. The most impressive of the narrative’s character arcs is Neku, who exemplifies the “redeemable asshole” trope splendidly. All the while, the game delves into pertinent themes that take full advantage of the modern setting.

George Carlin once discerned the difference between an “old fart” and an “old fuck” in one of his stand-up routines. An old fart is someone who is a grouch because of their advanced age wearing on them, while an “old fuck” is someone young who gripes with the world. For the latter, I can’t think of a better term to assign to our youthful yet curmudgeonly protagonist Neku. Our orange-haired misfit roams the streets of Shibuya, claiming that he “doesn’t understand people,” blocking out the irritating audible pollution comprised of the inane squawking of the people surrounding him. He wears a constant grimace on his face, and the common social niceties understood among most people are lost on him. The game needn’t provide a detailed backstory as to why Neku acts this way, for this is common amongst young men his age. I should know, as I, too, had a pair of headphones like Neku’s when I was a teenager, and I used them for the exact same purpose.

Like extracurricular after-school activities, The Reaper’s game forces Neku to interact with others for his own good. While Neku is the proverbial horse and the game is the water, he’ll only humor taking a drink for self-preservation when things get tense. At the start of the game, he’s a stubborn, insufferable prick, and the player will feel sorry for Shiki for having to have him contractually chained to him. Neku treats her like the scum between his toes, even physically lashing out at her when he’s annoyed with her. As much as the player might wish for Shiki to throw Neku into an oncoming bus, Neku must be antagonistic to this extent to illustrate that he’s Shiki’s foil. She’s kind, personable, perky, and has a passionate drive in life involving being a designer. While she’s the antithesis of Neku, she still carries the emotional baggage that all teenagers possess. She’s incredibly insecure about how she looks, and her entry fee into the Reaper’s game was her body which she swapped for the form of her “more attractive” friend Eri. By interacting with another human being willing to be patient with him, Neku learns the essential virtue of empathy. By the end of the week, he begins to tentatively change his tune. I’d comment that Shiki is another example of the tired manic pixie dream girl trope, but her gender is superfluous here. Neku is simply glad that he has made a friend.

A part of The World Ends With You’s subversiveness is not providing the shortest JRPG experience. The week’s time given to Neku and Shiki will diminish quickly before the player knows it, but there is far more of the game to explore. The setup for the second week expounds on more context missing from the beginning. Apparently, the players of this game are those who have recently died, and the underground is a state of purgatory. Playing the game to completion will grant the player an extra chance to return to the physical world and have another chance at life. Even though Neku succeeds in beating the game with flying colors, the Reapers exploit a loophole to keep him in the game. This time instead of his memories, his entry fee was Shiki, the person he cares for the most, a touching signification of how he’s grown. During these seven days, he tries to uncover the mystery behind his death with his new partner Joshua. If Shiki is Neku’s beacon of light, Joshua is the foul tempter in making Neku regress. Joshua shares the same contempt for humanity as Neku did, but with a sneering superiority complex and smug demeanor that makes him come across as sociopathic rather than an angsty kid. He controls the same as Shiki did but then develops god-like powers where he can deal massive damage shooting beams of energy while levitating. He’s also a glitch in the matrix as he’s a living person who is actively participating in the game as a player. Neku must keep his guard around Joshua, especially since his memories have recovered vague recollections of Joshua being Neku’s murderer. Once they become clearer, it turns out that the Reaper Minamimoto killed Neku, and Joshua sacrifices himself to save Neku at the end of the second week. I didn’t like Joshua because he’s a smarmy cunt, but I can’t deny that his wildcard presence spices up the game’s narrative and adds a layer of mystique.

Unfortunately, Joshua’s selfless deed did not grant Neku another chance at life. In Neku’s third week, he partners up with Beats, a familiar face who is as seasoned with the Reaper’s game as Neku is at the point. Out of the game’s secondary characters, Beat is perhaps the most dynamic character next to Neku. Beats is a tall, blonde young man carrying around a skateboard whose vernacular mostly consists of hip malapropisms. He also compensates for his lack of intellectual acumen with his brutish strength. Beats is impulsively hot-headed and greatly impatient, which is why he’s partaking in this game in the first place. Rhyme, Beats’s partner in the first week who got erased, is revealed to be Beat’s younger sister who died trying to save Beats from another one of his rash decisions. When Beats became a Reaper during the second week, it was all a means to climb the ladder to become the game’s composer, the omnipotent game master. He did not seek power to abuse it but to amend his past mistakes and give his sister another chance at life. Beats is yet another character whose bad first impressions are changed, as the big lug has a heart of gold and the will of a warrior. It’s too bad he’s the clunkiest of the three partners in battle.

Surprisingly with all of this positive character growth, the game seems to vindicate Neku’s initial cynical outlook. Through interacting with the people of Shibuya by scanning them and hearing their woes, the game portrays them as pitiable, materialistic, and comically impressionable. The ward of Tokyo is practically a glorified shopping mall, all with the gaudy excess that comes from the capitalist hub. Neku can purchase a number of clothes from a myriad of different flashy designer brands, but most of them all have the same stats. The constant flow of yen earned during battle and through disposing of pins guarantees that Neku will never be penniless, giving more of an emphasis on the frivolity of the culture. The game overtly comments on the farce of fads and capitalist practices when the Shadow Ramen store is doing better than its neighbor only because it’s trendy and has a celebrity endorsement, even though the more humble one has far superior food. The game shows that people are easily influenced by the most superficial things. A business executive makes all his important decisions by consulting a Shogi board that Neku manipulates. In extreme cases, the Reapers use the pins they’ve helped make popular to control the population of Shibuya. It turns them into pod people, but one could infer that the game assesses that they already were.

With all of this in consideration, the game conveys the message that despite the inane bullshit of modern life, one still can’t tune it out. Mr. Hanekoma, a respectable artist and game moderator, expresses to Neku the idea behind the title, “the world ends with you.” It means that in the bubble one encases themselves in when one wishes to be the ruler of their own space, one willfully blocks out the organic elements of life that make it meaningful. A bubble is only so big, which is a shame because the world is vast and filled with beautiful things. Similar to Persona, The World Ends With You expresses that friendship is one of the most integral aspects of modern life that conquers all insipid modernities. When Neku reunites with all his partners in the fabled Shibuya River and defeats the game’s conductor, Megumi, Joshua reveals himself as the game’s composer and finally grants Neku and the others a second chance at life. When they all come back, Shibuya hasn’t changed, but Neku and the others have expanded past their foreground by forming an organic bond beyond what they had in the underground. Neku even drops his headphones to signify that his world is much larger now. I came to somewhat of the same realization in the second half of my time in high school. I, like Neku, drowned out the world for the same reasons he did. By making myself vulnerable and letting people into my world, it inflated to a point where I was happier with my surroundings.

Square Enix is synonymous with the JRPG genre, especially that of the JRPGs we’ve all come to recognize as the genre’s traditional form. Decades later, it comes as no surprise that the developer had the potential to innovate once more and craft something unseen in the genre. The World Ends With You is a unique experience in so many ways that it’s astounding. The turn-based combat system that grew tiresome after the formula was exhausted upon repetition is shifted to some of the most kinetic gameplay seen in the genre, as well as making the best use of the DS’s format. However, the gameplay can be too ambitious for its own good, yet I can’t deny its originality. Even when the gameplay falters, The World Ends With You presents one of the most resonating stories seen in gaming, along with impeccably deep character writing. The World Ends With You the prime reason to own a DS, as far as I’m concerned.

------

Attribution: https://erockreviews.blogspot.com

High-concept premises are a requisite for the JRPG genre, almost as much as turn-based combat. Concepts involving role-playing usually entail a fantasy element to a certain degree, so why not go the distance and immerse yourself in something extraordinary? It helps that most of these games are developed in Japan, a country notable for conjuring up grandiose stories that forsake realism to the point of verging into biblically absurd territory. The World Ends With You follows suit with a creative premise whose rules exist outside the bounds of reality. Enter Neku: our youthful protagonist who skulks through the congested crossroads of an urban epicenter. His wispy presence in the crowd becomes so incorporeal to the point of being ghostly. Neku panics, but his existence is seemingly resurrected when he clenches onto a pin that mysteriously materializes in his hand. Suddenly, strange, hostile creatures appear along with ominous messages detailing that Neku has seven days to complete an unknown task. He then forms a pact with a girl named Shiki, who seems to be the only person who notices his presence. Their vague directive to complete in a week is then reduced to a mere 60 minutes, and failing to complete this task will result in “erasure,” a harrowing condemnation that Neku and Shiki most likely want to avoid. Immediately, the ambiguity of the scene combined with how urgently the game catapults the characters into the fray is a fantastic way to hook the player and make them interested in uncovering the mystery behind what is occurring.

By 2007, the “domestic JRPG” that Mother and Shin Megami Tensei established to deviate from the high-fantasy tropes in genre mainstays like Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest became almost as pervasive. Out of all the JRPG games set in modern times, The World Ends With You takes the most inspiration from the Persona games. One could make this correlation due to many factors like the Shibuya setting, the teenaged characters, or the juxtaposition between the real world and the fantasy realm, otherworld thinly veiled underneath the surface. Ultimately, The World Ends With You reminds me the most of Persona because the game is oozing with style. The comic book art of The World Ends With You is the crux of the game’s presentation, with characters conversing side by side with dueling speech bubbles between them. Characters, backgrounds, and the bustling streets of Shibuya are outlined so prominently, and the stilted images of the characters move with a certain restraint during conversations and cutscenes to pronounce the graphic novel aesthetic even further. No, the game’s style isn’t ripped from Persona, but what other JRPG series possesses a kind of hip, chic presentational flair to this degree? The World Ends With You might even take its visual finesse a step beyond Persona, as every character has so much drip that they're soaked, or at least that’s how the kids these days describe it. Whether they be nameless NPCs that Neku scans, the reapers scattered around the underground, or even Neku and the rest of the players, everybody looks uniquely voguish. The collective of Shibuya looks like they traipse down the fashion runway in Milan, or maybe Shibuya is the Japanese equivalent of the extravagant Italian city (after doing some research, it is). At least one character in any Persona game is guilty of committing fashion crimes, so The World Ends With You arguably has the advantage over its stylistic inspiration for better consistency and a greater emphasis on overtly flaunting its panache.

After the opening sequence, The World Ends With You grants the player context behind what is happening to Neku and Shiki. By some circumstances, both characters have been hurled into a frantic game that takes place on the streets of Shibuya. The game exists in a subconscious realm called “the underground,” where the player can interact with civilians but not vice versa. Two players must play cooperatively, and both of them have to meet one objective under a certain time constraint. Usually, the mission entails the players arriving somewhere in Shibuya, with hooded (hoodies) pawns called Reapers impeding the player’s course to their goal. Reapers assign tasks to the players that range in objectives, and completing these tasks grants the player past the forcefield wall the Reapers erected. As tense as the beginning scene made the game out to be, the player (meaning the player of the video game in this context) can approach each day at a leisurely pace. Days usually begin with Neku and his partner at Scramble Crossing, a medium point situated appropriately between all other Shibuya districts. Sometimes, missions will be more circuitous as Neku helps reapers and citizens by finding the power source for a concert stage, finding a stolen microphone, aiding the owner of a failing ramen shop against its nearby competitor, etc. Overall, every mission presented daily in The World Ends With You is supported by exposition rather than gameplay. Running around Shibuya never grates on the player because at least the narrative always offers something interesting each day that furthers the plot. However, navigating through Tokyo’s ritzy ward is not a straightforward endeavor. Attempting to find a specific destination in Shibuya in relation to the starting point of Scramble Crossing is liable to get the player as lost as if they were hiking through the woods at night because the map of Shibuya present in the pause menu is the least reliable reference I’ve seen in a video game. The district map pinpoints the player’s location, but the surrounding areas are labeled in letter abbreviations that do not match the area's name. Earlier in the game, this isn’t so much of an issue, for the logical trajectory to the goal is to follow the reapers. Later on, when the Reapers go rogue and start attacking Neku, the game penalizes the player for retreading their steps in trying to find their destination. If I have to scour the internet for a fan-made map when the one the game provides isn’t satisfactory, something is seriously wrong.

Between walking aimlessly around Shibuya lies the real appeal of The World Ends With You: the combat. The way in which The World Ends With You innovates on typical JRPG battles is the true mark of the game’s ingenuity. Instead of swords, arrows, guns, or baseball bats, Neku is armed with an arsenal of pins. Similarly to the guns in the Persona games, the power of these seemingly innocuous pins is unlocked through the metaphysical properties of the underground. During combat, activating the pin's powers depends on its unique nature. The first combat pin given to Neku is a fire pin in which dragging the DS stylus across the screen engulfs the field in flames, damaging any enemies that come into contact. Other pins involve tapping the screen to unleash energy projectiles, locking on enemies to disperse rounds of rapid-fire bullets, summoning a line of ice pillars to stab enemies from the ground, a current that sprinkles the stage with volts of electricity, drawing an oval to send a rogue ball of energy flailing around the stage or summon boulders that careen down from the sky, etc. There is even a pin that paralyzes enemies with sonic sound waves if the player blows into the DS mic, a surefire way to make the player look like a jackass and make them weary about playing video games in public ever again. One Reaper task forces the player to equip only these pins in battle, so make sure to find sanctuary before coming across this point in the game. I’m intentionally glancing over some of the pins because the variety of different pins with different abilities is too numerous for comprehension. Neku’s pin inventory is so massive that it would make an eagle scout feel unaccomplished. Unfortunately, the amount of pins makes Neku’s inventory too congested. Purchasing pins from Shibuya’s various shops is a viable option to increase Neku’s array of weaponry, but the game will rain pins down on Neku after each battle like confetti. No matter how many of the same type Neku has, each pin is accounted for in an individual slot in the inventory. I couldn’t count how many Natural Puppy boomerang pins I had by the end of the game. Fortunately, the player can cash them out for a number of yen, and the strongest pins with a maximum experience level are listed separately. Still, the game should’ve piled the pins of the same type in one slot so the player wouldn’t have to scroll through multiple tabs. That is my sole grievance with the pin system. Otherwise, they serve as an incredibly engaging way to shake up the usual JRPG action. Mixing and matching combinations of pins guarantees that combat will never feel stale, as well as taking advantage of the unique utility of the DS and making something practical of it.

Much to Neku’s chagrin, he cannot test these weaponized pins on Shibuya’s bystanders. Enemies in The World Ends With You are referred to as “the noise,” creatures that inhabit the ethereal space of the underground. When Neku scans an area, multiple red and orange symbols are seen floating around the air like macroscopic germs. Touching one or more of these symbols will trigger a battle between potentially several different noise creatures. All the noise are a warped variation of real-life animals ranging from frogs, wolves, bats, jellyfish, kangaroos, etc. The developers even took some creative liberties with the inclusion of mythical dragons and the extinct wooly mammoth into the mix. All of the noise have a base color at their earliest encounter, but they progressively don a wide span of complexions that come with a higher difficulty level. Approaching the noise is something that the game leaves entirely in the player’s court. Unless the player is forced to face the noise for a Reaper task, they can vanquish as many of the buggers as they see fit. Tapping the various noise symbols in succession will “chain” multiple rounds with the noise, which becomes an endurance test depending on how many bouts the player willfully imposes on themselves. I recommend chaining enemies because doing so will net the player more substantial rewards. Blackish noise symbols break the rules a bit as these corrupted noises will quickly swarm the player instead of letting the player choose them. Their defense is staggeringly higher than average noise, and they insist that the player mustn't escape during battle. If combat becomes too taxing, it’s entirely the player’s fault. When the player bites off more than they can chew, the game also allows the player to restart the battle or set the difficulty to easy. I find this to be a bit patronizing, as I would rather have the option to change my selection of pins if I fail. Other than that, the game’s approach of encouraging the player to engage in combat rather than bombarding them with random encounters is quite refreshing. Plus, the noise is all as eclectic as the pins Neku uses to fight them, assuring that the player will never tire of combat due to the overall eclecticism. That, and I enjoyed seeking out new types of noise because their names listed in the compendium are all music genre related, something that tickles my music nerd fancy. “Shrew Gazer” and “Jelly Madchester” almost verge into bad pun territory, but what other video game, much less a JRPG, explicitly references these genres?

Teamwork is imperative in the game that The World Ends With You presents. The Reapers may be sadists, but even they wouldn’t leave a poor player to their own devices. A pact between Neku and Shiki is made to withstand the noise and all the other hurdles the underground might toss, which means that the player will be controlling Neku and Shiki. However, this dynamic isn’t executed like your average one-player video game team. Using the distinctive technology of the DS, the player will control Neku and Shiki simultaneously. For those of you who haven’t played this game and feel weary with this aspect in mind, I can’t blame you one bit. At least the turn-based element of normal JRPG combat involves focusing on one party member per turn. Attempting to juggle The World Ends With You’s fast-paced combat with two party members using unorthodox tools like the DS stylus may seem too overwhelming. In execution, however, the developers succeeded in making it manageable. The trick to pulling it off is making the control scheme of Neku’s partner simple. Shiki attacks in the top half of the two DS screens, sicing her animated stuffed cat on the noise with the D-Pad. Holding down the left or right tabs on the D-Pad is all the player has to do to deal sufficient damage to the noise as Shiki, and, fortunately, the duplicate noise seen on both screens is the same enemy with the same amount of health. Fusion attacks where Neku and Shiki perform a collaborative super move can be unlocked by executing different combos on the D-pad with Shiki, but I’ve found that the game grants this to the player by only mashing in one cardinal direction. After all, the developers understand that juggling two characters with two different move sets is a daunting exercise.

That is, they sympathize with the player on this front until it comes time to fight a boss. Bosses in The World Ends With You are gargantuan, heavily resistant foes whose health bars have colored layers that the player must slowly dwindle. Durability is not the issue here. The developers affirm the worries some might have had about the practicality of the game’s combat with the bosses. Frequently, Neku and his partner must take turns depleting two separate health bars, and the character who isn’t fighting the boss on their screen does not get a chance to relax as they still have to contend with smaller enemies. Either that or they must complete a portion of the fight that allows the other character to damage the boss. Neku and his partner don’t share a health bar, but if one character is beaten within an inch of their life, the other suffers by taking more damage upon being hit. I’m not entirely sure if it's due to my lack of peripheral vision, but the scatterbrained double tasking needed to defeat these bosses is unfair. Either the game could've given the player a choice to use the top screen, or co-op play should’ve been implemented.

The World Ends With You’s ambitions regarding the divergent gameplay can be questionable. However, the same cannot be said for the narrative substance that upholds it. The World Ends With You produces some of the most dynamic and nuanced characters I’ve seen in any video game. The most impressive of the narrative’s character arcs is Neku, who exemplifies the “redeemable asshole” trope splendidly. All the while, the game delves into pertinent themes that take full advantage of the modern setting.

George Carlin once discerned the difference between an “old fart” and an “old fuck” in one of his stand-up routines. An old fart is someone who is a grouch because of their advanced age wearing on them, while an “old fuck” is someone young who gripes with the world. For the latter, I can’t think of a better term to assign to our youthful yet curmudgeonly protagonist Neku. Our orange-haired misfit roams the streets of Shibuya, claiming that he “doesn’t understand people,” blocking out the irritating audible pollution comprised of the inane squawking of the people surrounding him. He wears a constant grimace on his face, and the common social niceties understood among most people are lost on him. The game needn’t provide a detailed backstory as to why Neku acts this way, for this is common amongst young men his age. I should know, as I, too, had a pair of headphones like Neku’s when I was a teenager, and I used them for the exact same purpose.

Like extracurricular after-school activities, The Reaper’s game forces Neku to interact with others for his own good. While Neku is the proverbial horse and the game is the water, he’ll only humor taking a drink for self-preservation when things get tense. At the start of the game, he’s a stubborn, insufferable prick, and the player will feel sorry for Shiki for having to have him contractually chained to him. Neku treats her like the scum between his toes, even physically lashing out at her when he’s annoyed with her. As much as the player might wish for Shiki to throw Neku into an oncoming bus, Neku must be antagonistic to this extent to illustrate that he’s Shiki’s foil. She’s kind, personable, perky, and has a passionate drive in life involving being a designer. While she’s the antithesis of Neku, she still carries the emotional baggage that all teenagers possess. She’s incredibly insecure about how she looks, and her entry fee into the Reaper’s game was her body which she swapped for the form of her “more attractive” friend Eri. By interacting with another human being willing to be patient with him, Neku learns the essential virtue of empathy. By the end of the week, he begins to tentatively change his tune. I’d comment that Shiki is another example of the tired manic pixie dream girl trope, but her gender is superfluous here. Neku is simply glad that he has made a friend.

A part of The World Ends With You’s subversiveness is not providing the shortest JRPG experience. The week’s time given to Neku and Shiki will diminish quickly before the player knows it, but there is far more of the game to explore. The setup for the second week expounds on more context missing from the beginning. Apparently, the players of this game are those who have recently died, and the underground is a state of purgatory. Playing the game to completion will grant the player an extra chance to return to the physical world and have another chance at life. Even though Neku succeeds in beating the game with flying colors, the Reapers exploit a loophole to keep him in the game. This time instead of his memories, his entry fee was Shiki, the person he cares for the most, a touching signification of how he’s grown. During these seven days, he tries to uncover the mystery behind his death with his new partner Joshua. If Shiki is Neku’s beacon of light, Joshua is the foul tempter in making Neku regress. Joshua shares the same contempt for humanity as Neku did, but with a sneering superiority complex and smug demeanor that makes him come across as sociopathic rather than an angsty kid. He controls the same as Shiki did but then develops god-like powers where he can deal massive damage shooting beams of energy while levitating. He’s also a glitch in the matrix as he’s a living person who is actively participating in the game as a player. Neku must keep his guard around Joshua, especially since his memories have recovered vague recollections of Joshua being Neku’s murderer. Once they become clearer, it turns out that the Reaper Minamimoto killed Neku, and Joshua sacrifices himself to save Neku at the end of the second week. I didn’t like Joshua because he’s a smarmy cunt, but I can’t deny that his wildcard presence spices up the game’s narrative and adds a layer of mystique.

Unfortunately, Joshua’s selfless deed did not grant Neku another chance at life. In Neku’s third week, he partners up with Beats, a familiar face who is as seasoned with the Reaper’s game as Neku is at the point. Out of the game’s secondary characters, Beat is perhaps the most dynamic character next to Neku. Beats is a tall, blonde young man carrying around a skateboard whose vernacular mostly consists of hip malapropisms. He also compensates for his lack of intellectual acumen with his brutish strength. Beats is impulsively hot-headed and greatly impatient, which is why he’s partaking in this game in the first place. Rhyme, Beats’s partner in the first week who got erased, is revealed to be Beat’s younger sister who died trying to save Beats from another one of his rash decisions. When Beats became a Reaper during the second week, it was all a means to climb the ladder to become the game’s composer, the omnipotent game master. He did not seek power to abuse it but to amend his past mistakes and give his sister another chance at life. Beats is yet another character whose bad first impressions are changed, as the big lug has a heart of gold and the will of a warrior. It’s too bad he’s the clunkiest of the three partners in battle.

Surprisingly with all of this positive character growth, the game seems to vindicate Neku’s initial cynical outlook. Through interacting with the people of Shibuya by scanning them and hearing their woes, the game portrays them as pitiable, materialistic, and comically impressionable. The ward of Tokyo is practically a glorified shopping mall, all with the gaudy excess that comes from the capitalist hub. Neku can purchase a number of clothes from a myriad of different flashy designer brands, but most of them all have the same stats. The constant flow of yen earned during battle and through disposing of pins guarantees that Neku will never be penniless, giving more of an emphasis on the frivolity of the culture. The game overtly comments on the farce of fads and capitalist practices when the Shadow Ramen store is doing better than its neighbor only because it’s trendy and has a celebrity endorsement, even though the more humble one has far superior food. The game shows that people are easily influenced by the most superficial things. A business executive makes all his important decisions by consulting a Shogi board that Neku manipulates. In extreme cases, the Reapers use the pins they’ve helped make popular to control the population of Shibuya. It turns them into pod people, but one could infer that the game assesses that they already were.

With all of this in consideration, the game conveys the message that despite the inane bullshit of modern life, one still can’t tune it out. Mr. Hanekoma, a respectable artist and game moderator, expresses to Neku the idea behind the title, “the world ends with you.” It means that in the bubble one encases themselves in when one wishes to be the ruler of their own space, one willfully blocks out the organic elements of life that make it meaningful. A bubble is only so big, which is a shame because the world is vast and filled with beautiful things. Similar to Persona, The World Ends With You expresses that friendship is one of the most integral aspects of modern life that conquers all insipid modernities. When Neku reunites with all his partners in the fabled Shibuya River and defeats the game’s conductor, Megumi, Joshua reveals himself as the game’s composer and finally grants Neku and the others a second chance at life. When they all come back, Shibuya hasn’t changed, but Neku and the others have expanded past their foreground by forming an organic bond beyond what they had in the underground. Neku even drops his headphones to signify that his world is much larger now. I came to somewhat of the same realization in the second half of my time in high school. I, like Neku, drowned out the world for the same reasons he did. By making myself vulnerable and letting people into my world, it inflated to a point where I was happier with my surroundings.

Square Enix is synonymous with the JRPG genre, especially that of the JRPGs we’ve all come to recognize as the genre’s traditional form. Decades later, it comes as no surprise that the developer had the potential to innovate once more and craft something unseen in the genre. The World Ends With You is a unique experience in so many ways that it’s astounding. The turn-based combat system that grew tiresome after the formula was exhausted upon repetition is shifted to some of the most kinetic gameplay seen in the genre, as well as making the best use of the DS’s format. However, the gameplay can be too ambitious for its own good, yet I can’t deny its originality. Even when the gameplay falters, The World Ends With You presents one of the most resonating stories seen in gaming, along with impeccably deep character writing. The World Ends With You the prime reason to own a DS, as far as I’m concerned.

------

Attribution: https://erockreviews.blogspot.com