It's very difficult for me to think about Dear Esther because I get so easily overtaken by the discourse surrounding the game. In 2012 Dear Esther was, like, the hot button topic in video games. Many people - many professional game critics from mainstream outlets! - were slamming out paragraphs about how Dear Esther "isn't a game" to their readers, or expressing smug disinterest in what Dear Esther was doing on podcasts. The understanding was that, in spite of the fact that Dear Esther is a game, in the material sense, and that it could be played and completed like a game, it also was a non-game game, a game that fulfilled the parameters of a game but that, for philosophical reasons, wasn't really a game. Dear Esther was apprehended as a kind of pure antithesis to whatever it was that video games do, as it was understood in 2012, something that needed to be demeaned and forgotten so that games, as they were currently understood, could continue to be produced.

Playing it now, all that anxiety feels so...quaint. But for an audience who experienced a game like Uncharted 2 as the pinnacle of video game narrative craft, the alienation makes some sense. Dear Esther is this shiftless, languidly-paced narrative object that very intentionally avoids direct apprehension. For many players, this was something totally new.

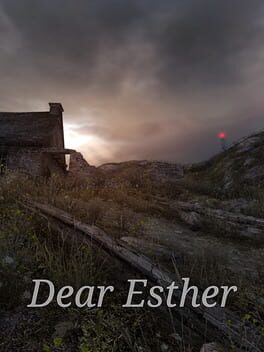

The game, in total, consists only of a walk along an island in the first person perspective, accompanied by dynamic narration that changes slightly each time the game is played. This narrator provides conflicting information and is only semi-coherent. Even the game world uses props which change from playthrough to playthrough; Esther appears to be a woman who died in a car crash, but only sometimes does the player find sonograms around the island. Sometimes the narrator seems to be tracing the history of the island as he goes, and other times seems to be producing a hoax to confuse future historians.

There's this pervasive sense of defeat within the game, the sense that everything that's ever mattered has already happened and that any end to the story is therefore arbitrary. The narrator discusses his kidney stones and his injuries from a fall, and sometimes the island visually echoes his body back to him; in one playthrough, as I explored the cave section, the narrator described the way people peered over him from a hospital bed as I passed under a massive crater in the earth which framed the moon like an eyeball. There's this sense that this island full of junk is the narrator, and that as he gets deeper and deeper into the island the metaphysical connection he shares with it becomes more and more deeply tied to his body. But the narrator has also finished with life, turning the island into a kind of purgatory. This makes for a memorable tone-piece, if not a comprehensively good game.

I always get the sense that something's missing from Dear Esther, though, like it's one good ingredient away from transforming itself into something bigger, more profound than it ended up being. I think it's the writing. Dear Esther's script seems like it was designed in a lab to elicit eyerolls. The visual design, the pacing, the music, they're all making these interesting, big moves, but the script can't capture the mood, stumbling towards poetic obscurity without ever managing to paint the game's emotional landscape. In one particularly embarrassing moment, the narrator says that Esther's car accident 'rendered her opaque,' which is, in all the ways that matter, not what opaque means, or what being 'rendered opaque' figuratively indicates.

Still, there's something here. If I can say anything positive about Dear Esther, it's this: I have forgotten way more about most games I've played, which are dense with filler combat encounters, than I remember. But I remember how playing Dear Esther made me feel.

Playing it now, all that anxiety feels so...quaint. But for an audience who experienced a game like Uncharted 2 as the pinnacle of video game narrative craft, the alienation makes some sense. Dear Esther is this shiftless, languidly-paced narrative object that very intentionally avoids direct apprehension. For many players, this was something totally new.

The game, in total, consists only of a walk along an island in the first person perspective, accompanied by dynamic narration that changes slightly each time the game is played. This narrator provides conflicting information and is only semi-coherent. Even the game world uses props which change from playthrough to playthrough; Esther appears to be a woman who died in a car crash, but only sometimes does the player find sonograms around the island. Sometimes the narrator seems to be tracing the history of the island as he goes, and other times seems to be producing a hoax to confuse future historians.

There's this pervasive sense of defeat within the game, the sense that everything that's ever mattered has already happened and that any end to the story is therefore arbitrary. The narrator discusses his kidney stones and his injuries from a fall, and sometimes the island visually echoes his body back to him; in one playthrough, as I explored the cave section, the narrator described the way people peered over him from a hospital bed as I passed under a massive crater in the earth which framed the moon like an eyeball. There's this sense that this island full of junk is the narrator, and that as he gets deeper and deeper into the island the metaphysical connection he shares with it becomes more and more deeply tied to his body. But the narrator has also finished with life, turning the island into a kind of purgatory. This makes for a memorable tone-piece, if not a comprehensively good game.

I always get the sense that something's missing from Dear Esther, though, like it's one good ingredient away from transforming itself into something bigger, more profound than it ended up being. I think it's the writing. Dear Esther's script seems like it was designed in a lab to elicit eyerolls. The visual design, the pacing, the music, they're all making these interesting, big moves, but the script can't capture the mood, stumbling towards poetic obscurity without ever managing to paint the game's emotional landscape. In one particularly embarrassing moment, the narrator says that Esther's car accident 'rendered her opaque,' which is, in all the ways that matter, not what opaque means, or what being 'rendered opaque' figuratively indicates.

Still, there's something here. If I can say anything positive about Dear Esther, it's this: I have forgotten way more about most games I've played, which are dense with filler combat encounters, than I remember. But I remember how playing Dear Esther made me feel.