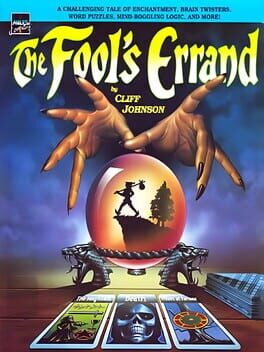

The fool's errand is a puzzle game that makes heavy use of a story based on the tarot deck.

Reviews View More

I played until the emulator crashed. It was sometimes torture but it was really cool torture and when it wasn't torture it was pretty cool! I love short stories and riddles and puzzles so this is super up my alley. I'm just kinda soured by the circumstances behind my run. Likely gonna pick up on the playthrough some other time when I can play it in a more stable environment.

From my blog, Arcade Idea.

As wont as I am to call everything some kind of "adventure game", citing the enormous and cross-genre influence of Colossal Cave Adventure [1975/77], this is pointedly trying NOT to be an adventure game, for all its resemblance. You can tell, because it has an adventure game inside of itself, which exists to parody adventure games and thereby define how this game is something else on a parallel track. This parody is a maze to fumble around in, bumping into various generic fantasy creatures (elves, pixies, and whatnot) who all block your path further into the maze until you bring them the item that will satisfy their varied and peculiar demands. It's a anthropomorphication of the classic "lock-and-key" inventory-management puzzle solved through complete exploration of every nook and cranny of a convoluted space that we see all over the place. It's quite the stretch to call this business "puzzles" at all, despite customary lingo. The "puzzles," such as they are in your usual adventure game, are not actually that mechanism but the obscuring of that mechanism, the creation of ambiguity around which well-hidden key goes with which lock and how you are meant to turn it, but it's here delivered with barebones set dressing which may be charming and witty but which does nothing to obscure its simplistic functioning to the player, rendering itself as dumb brute force that only tests patience and persistence — which is something you very often see in the usual non-parodic adventure game, too. Other than in this parody, there is actually no inventory system in this game, despite it having the bog-standard adventure game premise of collecting 14 treasures.

---- MUSICAL INTERLUDE: LL Cool J - My Rhyme Ain't Done [1987] -----

Like Sokoban [1982] or Tetris [1984] or Chain Shot [1985] (aka SameGame), The Fool's Errand [1987] brings to my little ad-hoc canon of video games a whole new idea of what a "video game puzzle" even can be. Unlike those games, it doesn't just give us one great puzzle mechanic, it brings us dozens of bespoke minigames, such that it's structurally reminiscent of art games like The Prisoner [1980] or Lifespan [1983]. It gives to the history a whole philosophy and tradition from outside video games, mixed with its own novel concepts that could only be done in video games. It is a digital work inspired by those magazines full of brain teasers you see at supermarket checkout stands and their more sophisticated and upscale sibling, those analog gamebooks that give its puzzling some kind of overarching throughline and cohesion through things like a narrative scaffolding or a meta-puzzle or even a real-world treasure hunt. This idea will stick with video games (see: The 7th Guest [1993], Professor Layton and the Curious Village [2007]) but rarely, if ever, will it be done quite as well as it is here (see: The 7th Guest [1993].)

(This isn't a review, but that's showing my hand: this is flat-out one of the best games I've ever played, hasn't "aged" a day for as much as I resent that framing, and I heartily recommend you play it if you're reading this and it at all intrigues you. It's free from the original creator Cliff Johnson now and one of the easiest to get running that I've ever played for this blog. Also, there was no natural place to note it in the body of the text, so here in the praise aside: this has its visual aesthetics totally on lock and is one of the most strikingly gorgeous games ever made, certainly made by 1987. I know I say that about every Macintosh game I play but I really really mean it here. I believe, though I'm not sure, that the beautiful artwork may have been the handiwork of someone named Brad Parker.)

The remaining puzzles not coming from that storied paradigm, which I'll address first, are instead highly interface-reliant. The Macintosh the game was made for has a mouse, and in the 80s this is still a bold novelty to experiment with, reminiscent of the way Nintendo DS games could get very excited over ways to ask the player to use the touchscreen. The Fool's Errand will ask you to move your mouse in specific choreographed ways, or to scan your mouse over the screen, or to keep your mouse still. The puzzles in this category are actually either tests of physical performance or, like the good versions of the lock-and-key puzzles it parodies, actually a puzzle of figuring out through its ambiguity and obscurity what exactly you're meant to do and then is no puzzle at all after.

This philosophy also shores up the more traditional-seeming puzzles. Some of the rules to various puzzles are plainly stated to the player, but others are quite deliberately not. Instead, the player finds themself already digitally bound by these rules and sometimes must deduce what those restrictions even are through experimenting within the interface, in a way that could not be replicated in print. Sometimes the game doesn't even tell the player the ultimate goal to be working towards.

If "an adventure game is a crossword at war with a narrative," as Graham Nelson wrote in 1995, then in The Fool's Errand the crossword wins possibly too handily to qualify. Many, perhaps most, of this game's puzzles revolve around some form of wordplay. Not as in puns and rhymes and such, but things like anagrams and cyphers and word searches and literal crosswords which attune you not so much to the sense or sound of the words but call attention to the particulars of its actual constituent letters. Often, The Fool's Errand will provide you with mere nonsense that the narrative transparently and comically strains to manufacture a half-logical pretext for using in a sentence, or literal gibberish to which you are to subject the same rigors as the perfectly cromulent words that are mixed right in with it.

Which brings me to the game's regard towards text, a subject on which I'd be tempted to call it "agnostic" if it wasn't so darn gnostic. As indicated, it structurally doesn't care about the "meaning" of text, and I mean that in the extremely basic "See Spot Run" sense where to "interpret" or "comprehend" the text is to firstly process the concepts of things like "run" and "see", and then secondly to pay attention to how these concepts one by one connect and build on one another through grammar into something that makes sense, typically something with some nominal weight of real-life apprehension underpinning its semiotics somewhere. The Fool's Errand has long passages of witty prose that operate on the level of comprehensibility perfectly well. There's a narrative about a peace between the four kingdoms of the realm that, under pressure of famine and petty grievances and misunderstandings and magical schemes, is threatening to curdle right back into war unless The Fool can stop it through collecting treasures and counterspells. It just is rarely interested in the various kinds of textual interpretation afforded by that approach; it's there, I could readily perform a deeper exegesis of it, but it's not the one that is incentivized and prized.

This is one crucial thing separating the player and the Fool, who they are aligned with but certainly do not directly control nor embody: The Fool thinks his world is real and approaches it as such, taking the information he is given as if it is has some weight of fact behind it, and when it does not seem to have such a significance, that this is a failure or malfunction. Other characters say things to The Fool that only make sense to the player who has access to the actual game bits, and The Fool "gets weary of such confusing talk and [does] not wish to consider [it] at all," or conversely he'll seriously entertain the aforementioned strained justifications for using silly words. He misapprehends a giant symbolic totem which then has to explicitly tell him that it is a symbol and what it is a symbol for twice over before he recognizes the pattern. This may be the very thing that makes him a fool: He has no access to nor awareness of the true nature of his universe — maybe you can see now what I meant by "gnostic" — which is apparent to the reader as fictional, linguistically-constructed, gamified, and dense with symbolism.

The kind of reading The Fool's Errand is more invested in is a pseudo-esotericist one. The whole game is tarot-themed, with all of its characters and events and many of its items drawn from the tarot traditions. This cues the reader to not read its prose so literally. A layperson with only the vaguest knowledge of tarot still knows that when they see objects in a tarot context that that object is not to be understood as just plain-and-simple being that object. A sword isn't a sword, it's a metaphor for... something (the layperson won't know what,) and even part of its own system of metaphors parseable only by those who have trained to parse it. But The Fool's Errand, as best as I can tell, doesn't much leverage the traditional divinatory significance and readings of, say, The Empress, or the actual contents of any of The Book Of Thoth it invokes repeatedly. The Fool's Errand's usage of the things on tarot cards seems to be uniquely its own takes, self-contained, self-explaining as much as they need to be, and only lightly and occasionally informed by pre-existing tarot usage, such as The Fool himself being the wandering protagonist. And thank goodness, for my sake. I don't know much about tarot, and did just enough research hitting the books to realize it wouldn't be terribly relevant for properly reading nor playing this particular game. (Though then again, I can hardly be terribly confident in that conclusion. If you're more steeped in tarot than I, please play the game and tell me that I'm wrong in the comments section below!) Thank goodness for its sake, too. The game casts The High Priestess as an outright cackling villain to be defeated triumphantly, which would be quite thematically alarming and even bizarrely misogynist if she were meant to represent the mysterious half of femininity, but she's not used that way.

Its engagement with the symbols of tarot is ultimately similar to its engagement with the symbols that constitute the alphabet. While esotericist reading strategies are often posited as a way to get beyond surfaces and see a deeper reality than even the one we think we are familiar with, The Fool's Errand instead playfully focuses its attention right in on the surface, steadily devaluing the idea of even an knowingly-illusory reality effect. The narration is mostly a veiled pretense that, like the game's many anagrams, needs to be unjumbled and deciphered for information that can then be instrumentalized for the purpose of organizing a big sliding image tile puzzle and sorting syllables. It encourages the player to plunder its prose for encrypted data in search of not secret knowledge but secret treasure. The game and eventually the player is far more concerned with the deft interplay of these symbols qua symbols connecting and collecting within its own systems than the things the symbols usually gesture at.

Folks, we might have ourselves a hypertext here. It's borderline, but it's striking to me. Structurally, while there's no direct hyperlinks from one page to the next, the game's story is conceptualized as pages to be approached in arbitrary order. There is a final and proper canonical order, but filling in its gaps is itself a major overarching challenge. The classic logic of this-then-that narrative order and causality is invoked but obscured and its discovery is gamified. Pages are locked off by puzzle completion, and the pages you start with unlocked aren't all the first pages. Instead, the minigames pitch you hither and tither across the text, most often to the next page but just as likely clear into a different chapter. The narrative's been fragmented into episodic vignettes, and they often seemed to me to make just as much sense in that secondary order as in the primary order, like when I had a hard time with a puzzle and the next page unlocked began with The Fool also feeling exhausted from effort. You can read the last page right from the start, and the best straightforward explanation of what's going on and what you are to do is found in the similarly-available second-to-last chapter. Spiritually, there's also a distinct bent to the game where it's majorly concerned with connections and greedily gathering data points up, and delighted by the sheer architecture of its own semiotic house of mirrors, with only light concern if any for what it all adds up to or points at that ultimately makes it feel to me more "postmodern" (and hypertextual) than esotericist.

It's interesting just how much of a boom there is for node-based narrative here in the late 1980s. Partially that's an artifact of my selections, but I know for sure they're actually surprisingly sparse in the early 1980s. We've sadly seen the last Infocom game we're going to see on this blog already, but as the little-disputed critical and commercial leading light of text adventures recedes, we see not only the market but the texts themselves fragmenting — if you're even going to be considering this sort of thing as occupying the same aesthetic and niche that that sort of thing does as well at other times, which has become a fundamental guiding principle of the concept of "interactive fiction" but only as it was formulated through controversy. The parser norms of interactive fiction will reassert themselves in an Infocom-derived renaissance in the mid-90s, but then around the turn of the 2010s it zags back to hypertext again, possibly for good. Alternatively, if you see hypertext as something wholly separate from and even defined against the parser adventure game tradition, as The Fool's Errand suggests it to be, this was a savvy move from the parser camp to rhetorically capture and encompass a now-more-popular genre entirely within its own tradition. Either way, that makes this little interregnum feel like foreshadowing, all the moreso because a lot of these games are being made by people who come from backgrounds outside of gaming working solo or close to it who thereby have more offbeat perspectives and tones than the programmers we've been used to.

-------------

Thanks to Monkeysky for getting inspired to play the game at the same time as me so we could talk about it. Thanks to hypodronic for the recommendation of Lon Milo DuQuette's "Understanding Aleister Crowley's Thoth Tarot" — didn't bear much fruit for this article but did give me some sea legs.

As wont as I am to call everything some kind of "adventure game", citing the enormous and cross-genre influence of Colossal Cave Adventure [1975/77], this is pointedly trying NOT to be an adventure game, for all its resemblance. You can tell, because it has an adventure game inside of itself, which exists to parody adventure games and thereby define how this game is something else on a parallel track. This parody is a maze to fumble around in, bumping into various generic fantasy creatures (elves, pixies, and whatnot) who all block your path further into the maze until you bring them the item that will satisfy their varied and peculiar demands. It's a anthropomorphication of the classic "lock-and-key" inventory-management puzzle solved through complete exploration of every nook and cranny of a convoluted space that we see all over the place. It's quite the stretch to call this business "puzzles" at all, despite customary lingo. The "puzzles," such as they are in your usual adventure game, are not actually that mechanism but the obscuring of that mechanism, the creation of ambiguity around which well-hidden key goes with which lock and how you are meant to turn it, but it's here delivered with barebones set dressing which may be charming and witty but which does nothing to obscure its simplistic functioning to the player, rendering itself as dumb brute force that only tests patience and persistence — which is something you very often see in the usual non-parodic adventure game, too. Other than in this parody, there is actually no inventory system in this game, despite it having the bog-standard adventure game premise of collecting 14 treasures.

---- MUSICAL INTERLUDE: LL Cool J - My Rhyme Ain't Done [1987] -----

Like Sokoban [1982] or Tetris [1984] or Chain Shot [1985] (aka SameGame), The Fool's Errand [1987] brings to my little ad-hoc canon of video games a whole new idea of what a "video game puzzle" even can be. Unlike those games, it doesn't just give us one great puzzle mechanic, it brings us dozens of bespoke minigames, such that it's structurally reminiscent of art games like The Prisoner [1980] or Lifespan [1983]. It gives to the history a whole philosophy and tradition from outside video games, mixed with its own novel concepts that could only be done in video games. It is a digital work inspired by those magazines full of brain teasers you see at supermarket checkout stands and their more sophisticated and upscale sibling, those analog gamebooks that give its puzzling some kind of overarching throughline and cohesion through things like a narrative scaffolding or a meta-puzzle or even a real-world treasure hunt. This idea will stick with video games (see: The 7th Guest [1993], Professor Layton and the Curious Village [2007]) but rarely, if ever, will it be done quite as well as it is here (see: The 7th Guest [1993].)

(This isn't a review, but that's showing my hand: this is flat-out one of the best games I've ever played, hasn't "aged" a day for as much as I resent that framing, and I heartily recommend you play it if you're reading this and it at all intrigues you. It's free from the original creator Cliff Johnson now and one of the easiest to get running that I've ever played for this blog. Also, there was no natural place to note it in the body of the text, so here in the praise aside: this has its visual aesthetics totally on lock and is one of the most strikingly gorgeous games ever made, certainly made by 1987. I know I say that about every Macintosh game I play but I really really mean it here. I believe, though I'm not sure, that the beautiful artwork may have been the handiwork of someone named Brad Parker.)

The remaining puzzles not coming from that storied paradigm, which I'll address first, are instead highly interface-reliant. The Macintosh the game was made for has a mouse, and in the 80s this is still a bold novelty to experiment with, reminiscent of the way Nintendo DS games could get very excited over ways to ask the player to use the touchscreen. The Fool's Errand will ask you to move your mouse in specific choreographed ways, or to scan your mouse over the screen, or to keep your mouse still. The puzzles in this category are actually either tests of physical performance or, like the good versions of the lock-and-key puzzles it parodies, actually a puzzle of figuring out through its ambiguity and obscurity what exactly you're meant to do and then is no puzzle at all after.

This philosophy also shores up the more traditional-seeming puzzles. Some of the rules to various puzzles are plainly stated to the player, but others are quite deliberately not. Instead, the player finds themself already digitally bound by these rules and sometimes must deduce what those restrictions even are through experimenting within the interface, in a way that could not be replicated in print. Sometimes the game doesn't even tell the player the ultimate goal to be working towards.

If "an adventure game is a crossword at war with a narrative," as Graham Nelson wrote in 1995, then in The Fool's Errand the crossword wins possibly too handily to qualify. Many, perhaps most, of this game's puzzles revolve around some form of wordplay. Not as in puns and rhymes and such, but things like anagrams and cyphers and word searches and literal crosswords which attune you not so much to the sense or sound of the words but call attention to the particulars of its actual constituent letters. Often, The Fool's Errand will provide you with mere nonsense that the narrative transparently and comically strains to manufacture a half-logical pretext for using in a sentence, or literal gibberish to which you are to subject the same rigors as the perfectly cromulent words that are mixed right in with it.

Which brings me to the game's regard towards text, a subject on which I'd be tempted to call it "agnostic" if it wasn't so darn gnostic. As indicated, it structurally doesn't care about the "meaning" of text, and I mean that in the extremely basic "See Spot Run" sense where to "interpret" or "comprehend" the text is to firstly process the concepts of things like "run" and "see", and then secondly to pay attention to how these concepts one by one connect and build on one another through grammar into something that makes sense, typically something with some nominal weight of real-life apprehension underpinning its semiotics somewhere. The Fool's Errand has long passages of witty prose that operate on the level of comprehensibility perfectly well. There's a narrative about a peace between the four kingdoms of the realm that, under pressure of famine and petty grievances and misunderstandings and magical schemes, is threatening to curdle right back into war unless The Fool can stop it through collecting treasures and counterspells. It just is rarely interested in the various kinds of textual interpretation afforded by that approach; it's there, I could readily perform a deeper exegesis of it, but it's not the one that is incentivized and prized.

This is one crucial thing separating the player and the Fool, who they are aligned with but certainly do not directly control nor embody: The Fool thinks his world is real and approaches it as such, taking the information he is given as if it is has some weight of fact behind it, and when it does not seem to have such a significance, that this is a failure or malfunction. Other characters say things to The Fool that only make sense to the player who has access to the actual game bits, and The Fool "gets weary of such confusing talk and [does] not wish to consider [it] at all," or conversely he'll seriously entertain the aforementioned strained justifications for using silly words. He misapprehends a giant symbolic totem which then has to explicitly tell him that it is a symbol and what it is a symbol for twice over before he recognizes the pattern. This may be the very thing that makes him a fool: He has no access to nor awareness of the true nature of his universe — maybe you can see now what I meant by "gnostic" — which is apparent to the reader as fictional, linguistically-constructed, gamified, and dense with symbolism.

The kind of reading The Fool's Errand is more invested in is a pseudo-esotericist one. The whole game is tarot-themed, with all of its characters and events and many of its items drawn from the tarot traditions. This cues the reader to not read its prose so literally. A layperson with only the vaguest knowledge of tarot still knows that when they see objects in a tarot context that that object is not to be understood as just plain-and-simple being that object. A sword isn't a sword, it's a metaphor for... something (the layperson won't know what,) and even part of its own system of metaphors parseable only by those who have trained to parse it. But The Fool's Errand, as best as I can tell, doesn't much leverage the traditional divinatory significance and readings of, say, The Empress, or the actual contents of any of The Book Of Thoth it invokes repeatedly. The Fool's Errand's usage of the things on tarot cards seems to be uniquely its own takes, self-contained, self-explaining as much as they need to be, and only lightly and occasionally informed by pre-existing tarot usage, such as The Fool himself being the wandering protagonist. And thank goodness, for my sake. I don't know much about tarot, and did just enough research hitting the books to realize it wouldn't be terribly relevant for properly reading nor playing this particular game. (Though then again, I can hardly be terribly confident in that conclusion. If you're more steeped in tarot than I, please play the game and tell me that I'm wrong in the comments section below!) Thank goodness for its sake, too. The game casts The High Priestess as an outright cackling villain to be defeated triumphantly, which would be quite thematically alarming and even bizarrely misogynist if she were meant to represent the mysterious half of femininity, but she's not used that way.

Its engagement with the symbols of tarot is ultimately similar to its engagement with the symbols that constitute the alphabet. While esotericist reading strategies are often posited as a way to get beyond surfaces and see a deeper reality than even the one we think we are familiar with, The Fool's Errand instead playfully focuses its attention right in on the surface, steadily devaluing the idea of even an knowingly-illusory reality effect. The narration is mostly a veiled pretense that, like the game's many anagrams, needs to be unjumbled and deciphered for information that can then be instrumentalized for the purpose of organizing a big sliding image tile puzzle and sorting syllables. It encourages the player to plunder its prose for encrypted data in search of not secret knowledge but secret treasure. The game and eventually the player is far more concerned with the deft interplay of these symbols qua symbols connecting and collecting within its own systems than the things the symbols usually gesture at.

Folks, we might have ourselves a hypertext here. It's borderline, but it's striking to me. Structurally, while there's no direct hyperlinks from one page to the next, the game's story is conceptualized as pages to be approached in arbitrary order. There is a final and proper canonical order, but filling in its gaps is itself a major overarching challenge. The classic logic of this-then-that narrative order and causality is invoked but obscured and its discovery is gamified. Pages are locked off by puzzle completion, and the pages you start with unlocked aren't all the first pages. Instead, the minigames pitch you hither and tither across the text, most often to the next page but just as likely clear into a different chapter. The narrative's been fragmented into episodic vignettes, and they often seemed to me to make just as much sense in that secondary order as in the primary order, like when I had a hard time with a puzzle and the next page unlocked began with The Fool also feeling exhausted from effort. You can read the last page right from the start, and the best straightforward explanation of what's going on and what you are to do is found in the similarly-available second-to-last chapter. Spiritually, there's also a distinct bent to the game where it's majorly concerned with connections and greedily gathering data points up, and delighted by the sheer architecture of its own semiotic house of mirrors, with only light concern if any for what it all adds up to or points at that ultimately makes it feel to me more "postmodern" (and hypertextual) than esotericist.

It's interesting just how much of a boom there is for node-based narrative here in the late 1980s. Partially that's an artifact of my selections, but I know for sure they're actually surprisingly sparse in the early 1980s. We've sadly seen the last Infocom game we're going to see on this blog already, but as the little-disputed critical and commercial leading light of text adventures recedes, we see not only the market but the texts themselves fragmenting — if you're even going to be considering this sort of thing as occupying the same aesthetic and niche that that sort of thing does as well at other times, which has become a fundamental guiding principle of the concept of "interactive fiction" but only as it was formulated through controversy. The parser norms of interactive fiction will reassert themselves in an Infocom-derived renaissance in the mid-90s, but then around the turn of the 2010s it zags back to hypertext again, possibly for good. Alternatively, if you see hypertext as something wholly separate from and even defined against the parser adventure game tradition, as The Fool's Errand suggests it to be, this was a savvy move from the parser camp to rhetorically capture and encompass a now-more-popular genre entirely within its own tradition. Either way, that makes this little interregnum feel like foreshadowing, all the moreso because a lot of these games are being made by people who come from backgrounds outside of gaming working solo or close to it who thereby have more offbeat perspectives and tones than the programmers we've been used to.

-------------

Thanks to Monkeysky for getting inspired to play the game at the same time as me so we could talk about it. Thanks to hypodronic for the recommendation of Lon Milo DuQuette's "Understanding Aleister Crowley's Thoth Tarot" — didn't bear much fruit for this article but did give me some sea legs.

This is one of the small handful of games I've ever emulated, and the first time I played it I nearly beat it - getting all the way to the final section where you have to find the names of the treasures - before stopping. Why i stopped I don't remember, I might have lost my progress or just stopped in a moment of difficulty and found it too daunting to return.

But, years later, something brought me back to this game, to play the entire thing again, and I'm glad it did. I became interested in this game when reading about its long-in-development sequel, but the game shouldn't just be known because of that, it should be known because it's just a great collection of puzzles, a virtual activity book for all ages, wrapped up in a very cool Tarot theme with nice blip and bloop sounds. Assembling the map is such a cool "meta puzzle", I'd love to have a poster of that on my wall. And words like "ERA" and "IVY" are now connected to this game in my head. I'll definitely play the sequel at some point.

But, years later, something brought me back to this game, to play the entire thing again, and I'm glad it did. I became interested in this game when reading about its long-in-development sequel, but the game shouldn't just be known because of that, it should be known because it's just a great collection of puzzles, a virtual activity book for all ages, wrapped up in a very cool Tarot theme with nice blip and bloop sounds. Assembling the map is such a cool "meta puzzle", I'd love to have a poster of that on my wall. And words like "ERA" and "IVY" are now connected to this game in my head. I'll definitely play the sequel at some point.

A fantastic puzzle game, and an experience akin to joining a cult and slowly going mad. The more you play this, the more you will begin to see indecipherable mishmashes of letters and numbers in your sleep, and the more Tarot symbolism will crowd the corners of your mind.

Because, as much as the game is about solving word searches, anagrams, mazes, and more, it's also--maybe more significantly-- about sheer, unadulterated vibes. The graphics in the Mac version are outstanding, depicting everything from evil high priestesses to men singing haunting songs to the visage of death itself in beautiful, stylized, black-and-white perfection. There is no sound or music, but there doesn't need to be.

The best part about The Fool's Errand is that it's completely surmountable, and most of its secrets are brilliantly hidden in plain sight. I played it with my dad (who played it first when he was in college, and then introduced it to me when I was young), and together we breezed through it in a few sittings. Not that it wasn't difficult--it just never completely stumped us, or felt cheap. Had I gone it alone, I think I would've been much worse off, so I definitely recommend playing it with someone, and bouncing ideas off one another.

Anyway. I might have nostalgia blinders on just ever-so-slightly, but I really do believe that this is a beautiful video game in almost every respect, and that Cliff Johnson is the genius that Johnathan Blow wishes he was.

Because, as much as the game is about solving word searches, anagrams, mazes, and more, it's also--maybe more significantly-- about sheer, unadulterated vibes. The graphics in the Mac version are outstanding, depicting everything from evil high priestesses to men singing haunting songs to the visage of death itself in beautiful, stylized, black-and-white perfection. There is no sound or music, but there doesn't need to be.

The best part about The Fool's Errand is that it's completely surmountable, and most of its secrets are brilliantly hidden in plain sight. I played it with my dad (who played it first when he was in college, and then introduced it to me when I was young), and together we breezed through it in a few sittings. Not that it wasn't difficult--it just never completely stumped us, or felt cheap. Had I gone it alone, I think I would've been much worse off, so I definitely recommend playing it with someone, and bouncing ideas off one another.

Anyway. I might have nostalgia blinders on just ever-so-slightly, but I really do believe that this is a beautiful video game in almost every respect, and that Cliff Johnson is the genius that Johnathan Blow wishes he was.