In my mind there are two types of indie games. Firstly, there are those that try to emulate their AAA counterparts, to varying degrees of success. Think Hollow Knight or Disco Elysium and how they are fairly standard attempts of an already existing genre, Metroidvania and CRPG respectively. Then there is the “weird idea” indies, that can vary from unique, one-mechanic experiences to small budget amalgamations from a small team. Think Downwell with its three button arcadey action, or Rain World with just how unique this “survival” game headed by a small handful of people is.

Both of these types of indie games can be successful, although they have different weaknesses in my mind. The first often doesn't have the budget or time to develop something with the scale of AAA releases. This is why they often emulate older, more niche genres. Hollow Knight isn’t competing with Red Dead Redemption, it's competing with Super Metroid (a game with less than 20 developers). This allows them to side step the pitfalls of being a small team, and why there are very few open-world indie games.

The second’s problem is that they often don't get fully fleshed out. Think QWOP or Flappy Bird, where the gameplay is unique, but it doesn’t go anywhere with the idea. This isn’t a given, I mentioned Downwell and it fits well into this category, but has enough unique content to warrant it being a full release. It’s short, it’s arcadey, and both of those factors help it to thrive under that very small development.

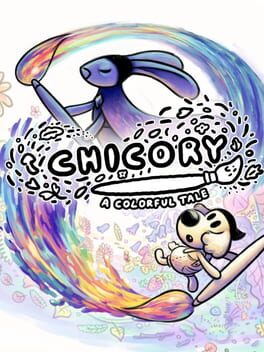

I say all of this to bring up that Chicory lies somewhere in between, and I think it’s the most interesting thing to talk about with it. It’s intriguing to think about an alternate timeline where Chicory leaned into either of these two indie archetypes. Chicory could very easily have just been a digital coloring book, nothing more than a collection of screenshots to color in just for the fun of it. Alternatively, Chicory could have leaned much harder into the puzzle and Metroidvania elements hiding beneath its surface, putting a higher emphasis on boss battles, scattering enemies all around the world, and slapping on a traditional combat system.

Chicory adopts the strengths of both game types in order to make something wholly unique, that still has all the substance of traditional titles. This isn’t to say that Chicory is flawless or above criticism, but solely that Chicory accomplishes something that very few others do. I think this is the indie dream: making something that can only come from the creativity and passion of a smaller team, but still making it a fully fledged release.

Chicory stars [insert food name here] and their journey of becoming the ‘Wielder,’ an individual tasked with bringing color to the world. For me at least, their name was Pizza. Pizza’s journey sprawls the providence of Picnic, a land filled with jungle, city, ocean, and mountain. As you progress, your main focus is to rid the land of a botanic plague, trees that stem from the previous Wielder. This core relationship, between your predecessor, Chicory, and you, is used to communicate a story about art, insecurity, and the creative process.

As you progress through the game, you continuously ‘level up’ your relationship with The Brush. This is manifested through new abilities that contribute to the aforementioned Metroidvania elements. This was the coolest part of the game in my opinion, and I was consistently surprised by both how unique the upgrades were, and how much they changed traversal throughout Picnic. Take the paint swimming for example. There are small passageways that Pizza can now fit through via swimming. This is the “lock & key” aspect synonymous with the genre. However, Chicory understands that abilities should have more impact on the game than just being that traditional “lock & key.” It adds additional utility to swimming, by allowing the player to move faster while swimming.

I know it sounds dumb to praise something as simple as a movement speed buff while swimming, but it goes beyond that. This acts as an incentive to paint in the world around you (something that matches well with the narrative) as well as rewarding players for going the extra step to color in the ground, with quicker movement. Metroidvanias are notorious for backtracking, and quicker backtracking cuts down on a lot of the tedium.

This extends to other abilities as well. The jump acts as a way to cross gaps that were previously uncrossable (“lock and key”). It also allows you to now jump off of cliff faces, meaning that you don’t have to redo cliff-swimming puzzles when moving backwards through an area. Swimming in water now allows you to cross bodies of water to access new areas (“lock and key”). However, most early areas are segmented by water, and this allows you to use rivers as shortcuts, once again cutting down on backtracking when you get this ability late in the game.

This was by far my favorite part of the game, seeing how well thought out each ability was, how many new routes were opened by each, and just how well they paired with the excellent level design.

The coloring aspect of the game is obviously the main selling point. Aside from knowing Lena Raine composed the soundtrack (they killed it), this was the only other thing I knew before heading into Chicory. In many ways, I don’t think they could improve on the coloring aspect of the game. So much effort went into this aspect of the game, and I would like to list a few that stood out to me.

1. Restricting the player to a set of 4 colors allows for three distinct outcomes. The first is that it allows the player to not get distracted choosing colors. Limitations breed creativity, at least that’s how the saying goes. The second is that by changing the color palette between zones, it allows for the areas to have distinct visual identities. This is an especially notable feat for a game that is all black and white outside of player input. The third is tied into the second, and how being given different colors for each zone affects how you approach coloring the landscape. Essentially, you avoid the monotony of coloring every repeat asset the same color across the whole game and you force the player to get creative with the given colors. Trying to choose what color to use for each object, while keeping consistent for an area, can be challenging while keeping visually appealing coloring.

2. Great lengths were taken to make the coloring easy for players. Not everyone is good at drawing (heaven knows I’m not) but they have given options to not just allow for unskilled artists to draw efficiently, but give freedom to talented artists. For example, you can hold down to fill an area. This looks nice, fills it to the edge, and fills large spaces quickly. Another example would be the quickly adjustable size of your brush. If you are solely focused on solving puzzles, you might equip the largest brush. If you are wanting to add lots of detail so that each object is more than just one color, you might have the smallest brush equipped along with the zoom in. If you want a comfortable middle ground, use the medium. It’s the small touches like this that allow for drawing to be as simple or complex as one might want.

3. There are additional unlocks that add complexity if the player wants it. Want to break the 4 color restriction? You can now customize a permanent (and optional!) selection of 8 chosen RGB values. Want to add detail quickly? There are brush textures that you can use to make surfaces striped, or polka dotted, or a mix of the two. Want to be given a straight-edge tool? There’s a brush for that. Want to change the otherwise static environment? Drop furniture you’ve found.

All of this is to say that the drawing in this game is made exceptionally well, especially with how it ties into gameplay elements. Most of the puzzles are crafted around drawing and simple platformers. The ‘bosses’ take damage via your scribbles. The drawing isn’t a gimmick, it's a core feature that Chicory wouldn’t be the same without.

However, it's the drawing that holds my one true gripe with the game. That of course is the decision to color in screens or not. These both come with downsides that I haven’t found a way to reconcile. Either the pacing is killed by coloring in each screen cleanly, taking great care to make it look good, or your game looks shitty, with blobs of ink cast awkwardly over the screen and most of the environment left in their original black and white state. Neither of these are very good options and I found myself flopping between them throughout the game's runtime.

In some areas, such as Banquet Rainforest and Dinners, I went to great lengths to color in the whole environment, sticking with a consistent coloring scheme for the whole area. I am really satisfied with how they look, and it adds a lot to the atmosphere of both areas to have a consistent visual identity. However, it took me a long time to color these in, especially with the Banquet Rainforest, an area that takes up a large portion of the overall gameworld and is filled with lots of little objects.

However, in some areas, such as Brunch Canyon and Spoons Island, I just rushed through without coloring much more than what was needed to solve puzzles. These areas were where I had the most fun, engaging with the puzzles in rapid succession. However, looking at the overworld map and just how blank it all looks left a hollow feeling that I didn’t experience with the other areas. Pizza is The Wielder after all, shouldn't they be coloring everything? It’s also worth mentioning how much I enjoyed returning to the areas I put effort into, because they looked so good! Alternatively, the areas that I mostly skipped, I ran through with guilt on repeat ventures.

This dual natured interaction with the coloring was something I struggled with for the whole game, and never found myself fully satisfied with either way. Maybe I was just really slow at coloring, and it’s more of an issue with me than the game, but I never found myself able to color quickly at a level that I found visually appealing.

My other big complaint was with the writing. Most games don’t have great, or really even good writing. Chicory falls into the trap where in an effort to keep interactions brief they skimp out on depth of characters. The other type of writing that I found to be annoying was the ‘quirky’ characters. Many writers, especially in games, fail to land non-conventional characters, and Chicory is no exception. By no means is the writing terrible in Chicory, but in comparison with the visuals and music, it definitely leaves a lot to be desired.

I liked the message of Chicory quite a lot. As someone who struggles to be motivated in their creative passions, it hit home pretty hard. Art is something that I place a high value on, maybe even the thing that I place the highest. Chicory not only reminded me that the people in our lives are what really matter, but also that I’m not worthless because of my lack of creative output. Thank you everyone who worked on the game, it’s something that my low self-esteem always needs to hear.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time with Chicory. I have a feeling that it will stick in my mind for a long time to come. It's the kind of game you wish you would've made, leaving that jealousy that others can be so talented and make such good art. The message of the game is pretty contrary to that feeling, but I'm only human. It's too relatable in a sense to see all the failure and struggle that artists go through. There's beauty everywhere, no matter how small. Even the janitor can create art, so why shouldn't I?

Both of these types of indie games can be successful, although they have different weaknesses in my mind. The first often doesn't have the budget or time to develop something with the scale of AAA releases. This is why they often emulate older, more niche genres. Hollow Knight isn’t competing with Red Dead Redemption, it's competing with Super Metroid (a game with less than 20 developers). This allows them to side step the pitfalls of being a small team, and why there are very few open-world indie games.

The second’s problem is that they often don't get fully fleshed out. Think QWOP or Flappy Bird, where the gameplay is unique, but it doesn’t go anywhere with the idea. This isn’t a given, I mentioned Downwell and it fits well into this category, but has enough unique content to warrant it being a full release. It’s short, it’s arcadey, and both of those factors help it to thrive under that very small development.

I say all of this to bring up that Chicory lies somewhere in between, and I think it’s the most interesting thing to talk about with it. It’s intriguing to think about an alternate timeline where Chicory leaned into either of these two indie archetypes. Chicory could very easily have just been a digital coloring book, nothing more than a collection of screenshots to color in just for the fun of it. Alternatively, Chicory could have leaned much harder into the puzzle and Metroidvania elements hiding beneath its surface, putting a higher emphasis on boss battles, scattering enemies all around the world, and slapping on a traditional combat system.

Chicory adopts the strengths of both game types in order to make something wholly unique, that still has all the substance of traditional titles. This isn’t to say that Chicory is flawless or above criticism, but solely that Chicory accomplishes something that very few others do. I think this is the indie dream: making something that can only come from the creativity and passion of a smaller team, but still making it a fully fledged release.

Chicory stars [insert food name here] and their journey of becoming the ‘Wielder,’ an individual tasked with bringing color to the world. For me at least, their name was Pizza. Pizza’s journey sprawls the providence of Picnic, a land filled with jungle, city, ocean, and mountain. As you progress, your main focus is to rid the land of a botanic plague, trees that stem from the previous Wielder. This core relationship, between your predecessor, Chicory, and you, is used to communicate a story about art, insecurity, and the creative process.

As you progress through the game, you continuously ‘level up’ your relationship with The Brush. This is manifested through new abilities that contribute to the aforementioned Metroidvania elements. This was the coolest part of the game in my opinion, and I was consistently surprised by both how unique the upgrades were, and how much they changed traversal throughout Picnic. Take the paint swimming for example. There are small passageways that Pizza can now fit through via swimming. This is the “lock & key” aspect synonymous with the genre. However, Chicory understands that abilities should have more impact on the game than just being that traditional “lock & key.” It adds additional utility to swimming, by allowing the player to move faster while swimming.

I know it sounds dumb to praise something as simple as a movement speed buff while swimming, but it goes beyond that. This acts as an incentive to paint in the world around you (something that matches well with the narrative) as well as rewarding players for going the extra step to color in the ground, with quicker movement. Metroidvanias are notorious for backtracking, and quicker backtracking cuts down on a lot of the tedium.

This extends to other abilities as well. The jump acts as a way to cross gaps that were previously uncrossable (“lock and key”). It also allows you to now jump off of cliff faces, meaning that you don’t have to redo cliff-swimming puzzles when moving backwards through an area. Swimming in water now allows you to cross bodies of water to access new areas (“lock and key”). However, most early areas are segmented by water, and this allows you to use rivers as shortcuts, once again cutting down on backtracking when you get this ability late in the game.

This was by far my favorite part of the game, seeing how well thought out each ability was, how many new routes were opened by each, and just how well they paired with the excellent level design.

The coloring aspect of the game is obviously the main selling point. Aside from knowing Lena Raine composed the soundtrack (they killed it), this was the only other thing I knew before heading into Chicory. In many ways, I don’t think they could improve on the coloring aspect of the game. So much effort went into this aspect of the game, and I would like to list a few that stood out to me.

1. Restricting the player to a set of 4 colors allows for three distinct outcomes. The first is that it allows the player to not get distracted choosing colors. Limitations breed creativity, at least that’s how the saying goes. The second is that by changing the color palette between zones, it allows for the areas to have distinct visual identities. This is an especially notable feat for a game that is all black and white outside of player input. The third is tied into the second, and how being given different colors for each zone affects how you approach coloring the landscape. Essentially, you avoid the monotony of coloring every repeat asset the same color across the whole game and you force the player to get creative with the given colors. Trying to choose what color to use for each object, while keeping consistent for an area, can be challenging while keeping visually appealing coloring.

2. Great lengths were taken to make the coloring easy for players. Not everyone is good at drawing (heaven knows I’m not) but they have given options to not just allow for unskilled artists to draw efficiently, but give freedom to talented artists. For example, you can hold down to fill an area. This looks nice, fills it to the edge, and fills large spaces quickly. Another example would be the quickly adjustable size of your brush. If you are solely focused on solving puzzles, you might equip the largest brush. If you are wanting to add lots of detail so that each object is more than just one color, you might have the smallest brush equipped along with the zoom in. If you want a comfortable middle ground, use the medium. It’s the small touches like this that allow for drawing to be as simple or complex as one might want.

3. There are additional unlocks that add complexity if the player wants it. Want to break the 4 color restriction? You can now customize a permanent (and optional!) selection of 8 chosen RGB values. Want to add detail quickly? There are brush textures that you can use to make surfaces striped, or polka dotted, or a mix of the two. Want to be given a straight-edge tool? There’s a brush for that. Want to change the otherwise static environment? Drop furniture you’ve found.

All of this is to say that the drawing in this game is made exceptionally well, especially with how it ties into gameplay elements. Most of the puzzles are crafted around drawing and simple platformers. The ‘bosses’ take damage via your scribbles. The drawing isn’t a gimmick, it's a core feature that Chicory wouldn’t be the same without.

However, it's the drawing that holds my one true gripe with the game. That of course is the decision to color in screens or not. These both come with downsides that I haven’t found a way to reconcile. Either the pacing is killed by coloring in each screen cleanly, taking great care to make it look good, or your game looks shitty, with blobs of ink cast awkwardly over the screen and most of the environment left in their original black and white state. Neither of these are very good options and I found myself flopping between them throughout the game's runtime.

In some areas, such as Banquet Rainforest and Dinners, I went to great lengths to color in the whole environment, sticking with a consistent coloring scheme for the whole area. I am really satisfied with how they look, and it adds a lot to the atmosphere of both areas to have a consistent visual identity. However, it took me a long time to color these in, especially with the Banquet Rainforest, an area that takes up a large portion of the overall gameworld and is filled with lots of little objects.

However, in some areas, such as Brunch Canyon and Spoons Island, I just rushed through without coloring much more than what was needed to solve puzzles. These areas were where I had the most fun, engaging with the puzzles in rapid succession. However, looking at the overworld map and just how blank it all looks left a hollow feeling that I didn’t experience with the other areas. Pizza is The Wielder after all, shouldn't they be coloring everything? It’s also worth mentioning how much I enjoyed returning to the areas I put effort into, because they looked so good! Alternatively, the areas that I mostly skipped, I ran through with guilt on repeat ventures.

This dual natured interaction with the coloring was something I struggled with for the whole game, and never found myself fully satisfied with either way. Maybe I was just really slow at coloring, and it’s more of an issue with me than the game, but I never found myself able to color quickly at a level that I found visually appealing.

My other big complaint was with the writing. Most games don’t have great, or really even good writing. Chicory falls into the trap where in an effort to keep interactions brief they skimp out on depth of characters. The other type of writing that I found to be annoying was the ‘quirky’ characters. Many writers, especially in games, fail to land non-conventional characters, and Chicory is no exception. By no means is the writing terrible in Chicory, but in comparison with the visuals and music, it definitely leaves a lot to be desired.

I liked the message of Chicory quite a lot. As someone who struggles to be motivated in their creative passions, it hit home pretty hard. Art is something that I place a high value on, maybe even the thing that I place the highest. Chicory not only reminded me that the people in our lives are what really matter, but also that I’m not worthless because of my lack of creative output. Thank you everyone who worked on the game, it’s something that my low self-esteem always needs to hear.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time with Chicory. I have a feeling that it will stick in my mind for a long time to come. It's the kind of game you wish you would've made, leaving that jealousy that others can be so talented and make such good art. The message of the game is pretty contrary to that feeling, but I'm only human. It's too relatable in a sense to see all the failure and struggle that artists go through. There's beauty everywhere, no matter how small. Even the janitor can create art, so why shouldn't I?

Consciovs

4 months ago