This review contains spoilers

The concept of a “tearjerker” is usually not associated with the medium of video games. In the realm of films, literature, and music, the tag is assigned to works that fit the bill either as a point of interest for those who want to expunge their emotions or a disclaimer if someone wants to keep their cheeks dry and cheery. Music is in a class of its own as the sonic art form tends to delve into one’s emotions more intimately no matter what the artist’s intentions were, or at least to a broader extent of the medium’s potential. For the narrative-focused mediums of film and literature, the writers must make a meticulous effort to direct their audience into flooding their living spaces with salty saline through the events of the story and the context of the character’s interactions. Since a large number of video games include traditional narratives with personable, dynamic characters, why isn’t anyone excited and or worried that one will cause them to be impacted by vulnerable feelings of overwhelming sadness? Well, video games had to evolve to achieve this sensation, as the earliest few eras of gaming were far too primitive to intermingle the narrative weight that would induce crying with the gameplay. That, and the inherent feeling that comes with playing games should be of elatement. After all, that is the primary objective of playing a game of any sort whether they be digital or not. However, video games possess a deeper layer of interactive complexities that games like hopscotch, gin and rummy, and all sports do not. Video games are art, goddammit, and one effective trait of fine art is the ability to make its audience cry. Emotional instances are known to pop up across a select few video games, but one game, in particular, was foretold to destroy the spirits of everyone who played it: indie developer Freebird Studio’s 2011 title To the Moon.

Already, the plot premise of To the Moon should slightly moisten the player’s eyes. An old man named John Wyles is lying on his deathbed, and his last wish before he passes into the eternal ether mirrors the fantasies expressed in early 20th-century cinema: a trip to the moon. Even in the fictitious realm of video games, there is no Make-A-Wish foundation for privileged senior citizens to fulfill such fanciful dying desires that only a handful of people on Earth have ever experienced. However, an organization called Sigmund Corp. can work around the expenses and general feasibility of this grand request by planting artificial experiences into the patient’s brain as they lie there comatose. Two doctors appointed by Sigmund Corp named Neil Watts and Eva Rosaline are on call to execute the mission by visiting John’s mansion and applying an apparatus to him while he lies in bed. Integrating these fake memories into John’s fading consciousness is quite the ordeal, so Neil and Eva must brew some coffee for the all-nighter they are about to undergo. As we speak, there should be at least a few choked-up throats upon reading what To the Moon’s narrative has to offer. The concept of death is an uncomfortable, bittersweet topic that will constantly nag us with feelings of dread throughout our time on Earth. The concept of death and dying is arguably the most universal human fear that crosses all cultural boundaries, even if the scattered earth civilizations have their interpretations of the inevitable. Because death and its implications are such a prevalent force while we are living, we do not need any context as to who John was as a human being to empathize with his critical condition.

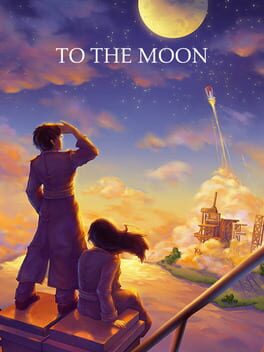

To the Moon’s premise hardly sounds like something a triple-A studio would produce, so expect the game’s presentation to display the minimalistic trappings of an indie studio. Specifically, To the Moon was developed with RPG Maker, a computer program downloadable by the general public to craft their own RPG games. To the Moon isn’t working with a modest sum of resources: it’s something any schmuck with Windows 7 could’ve conjured up in one afternoon. In all fairness, despite how cheap and unprofessional the base software of To the Moon’s development sounds, the final product could still ultimately prove substantial if the developers know how to work around the constraints of a pail bucket budget. Besides, I’ve always stated that any modern game rendered in the pixelated past of the medium always possesses an endearing quality, and To the Moon is no exception. With the pixelated format the game works with, To the Moon’s graphics strike a balance between cherubic and sublime. The chibi characters in the foreground contrast with the often picturesque displays of the backgrounds. Look at the sight of the nearby lighthouse peaking over the cliffside where John’s mansion is located and you’ll understand the visual dichotomy I’m attempting to illustrate. It’s beautiful but carries a sense of melancholy. Like most indie titles from the 21st century that use pixels as a driving force of their artistic direction, To the Moon still looks crisper and cleaner than what the big boys of the industry were working on in the later years of the previous century. It’s telling how far the medium has progressed when a program as accessible as this one outperforms anything made with an enormous budget only two decades prior.

Despite the name of the software that To the Moon was created in, the game is not an RPG of any sort. Our two protagonists fight a squirrel on the rocky road up to John’s house in a turn-based format, but this is a one-time snarky, ironic joke to throw off the expected precedent. No, the developers figured the tasteful way to gamify a story where an old man meets his timely demise is to render it into a point-and-click adventure title. With the conjoined Inception-esque apparatus, Neil and Eva can fully access every memory and experience from John’s storied life, or at least how John recalls them. Their objective is to redirect the course of John’s life through their minor alterations, simply by subtly or unsubtly passing the idea to visit the moon while he still had time. Neil and Eva know that timeliness is essential considering the host of the simulation could perish at any moment, so their first attempt is to grab him a few months before he’s bedridden to relay the idea. Unfortunately for them, John’s twilight years were rather occupied with other worries, such as aiding his dearly departed wife River when she was in hospice and how to feasibly move a grand piano up and down a flight of stairs. John is too long in the tooth to be considering the improbable goal of space travel, so Neil and Eva are forced to delve further into John’s past to find him at a more impressionable age. The rewinding process through John’s life is how the game implements the interactive point-and-click elements. To dig deeper into the strata of John’s life, Neil and Eva must find a memento whose resonance will serve as a portal to an earlier memory. Commonly used mementos include a bag that John carried around and a stuffed platypus plush owned by River. To activate the memento, Neil and Eva must find five pieces of contextual evidence behind the memento found in the same scene, usually after the conversational section between John and another person is finished. Oftentimes, the substance behind the gameplay in a point-and-click adventure is solving puzzles to progress, giving the player a hint of interactivity that will keep them engaged. To the Moon offers something in the same vein, but it's far too elementary. The five pieces of context needed for the memento are hidden in plain sight, and the area where they are all located is confined enough that finding all of them will most likely take a few minutes at most. When the five pieces are all assembled at the chosen memento, the player is transported to a puzzle section where they must align a picture by a 5X5 grid. This simple task will also prove to be quick and easy, as there is no time limit and no penalties for accidentally making the image less coherent. I always worry when narrative-focused video games sacrifice gameplay to fortify the story, and To the Moon is another example that will continue this concern.

Alright, so if To the Moon’s gameplay is effortless so as to not distract from the foreground of the narrative, certainly the game compensates with solid characters that drive the story’s intrigue. John, for example, has circled around the sun enough times to have experienced plenty of amazement and hardships, so traveling down the rabbit hole that is his entire life should ideally be interesting, right? Actually, John’s life is realistically mundane. In fact, the man led a pretty insular life with the same people. He married his high school girlfriend, proceeded to stay acquainted with his best friend Nick into adulthood, and has been kept company by his caretaker Lily, and her two children after his wife passed into old age. Upon exploring John’s past, it seems as if his wife, River, is the fascinating one by comparison as we learn about her diagnosis of Asperger's and how it correlates to why she obsessively makes origami bunnies that are strewn all over John’s basement. We never know what John’s former occupation was and how he could afford a countryside estate that overlooks a lighthouse. Whatever it was, I’m sure it was incredibly boring. It isn’t until Neil and Eva have to connect the bridge of John’s past to his early childhood that we discover that John’s existence hasn’t always been so spotless. For some reason, the time before John’s teenage years is obscured in a hazy shield of blankness, for his time-consuming beta blockers in the military (which is only explained through exposition and not experienced firsthand) have blocked it from view. After forcibly pushing past the impediment, we learn that John is suffering the trauma of losing his twin brother Joey in a pedestrian car accident when they were still in grade school. To retain some semblance of Joey’s presence on this earth, John subconsciously adopted all of his quirks such as his adoration for pickled olives. He also gained Joey’s fondness for the Animorphs books series, which means that this old geezer is a decrepit millennial, and the modern-day in this game is in the later decades of the 21st century. Thanks for making your target demographic (me) fret over their mortality, guys. Uncovering the pinnacle turning point in John’s life that shaped his present-day demeanor suddenly makes us invested in him and adds some spice to the humdrum future events we’ve already witnessed.

Where To the Moon has characters who have the personalities of a wet sock, the game also features those on the other end of the spectrum who are a bit much. Neil Watts, the male half of the Sigmund Corp duo, is…how do I put this nicely? He’s a real prick. He’s impatient, obnoxious, rude, and treats the job he’s doing with such callousness that it is practically offensive. In sensitive fields such as the one he specializes in, it’s understood that one has to harden their heart to deal with the heaviness of death. Still, Neil presents himself with such aloofness that he comes off as a clod. The game is somewhat aware of Neil’s flawed personality through his dynamic with Eva, the straight (wo)man on the job. She constantly reprimands Neil for his buffoonery not playfully as a couple with brewing sexual tension or as a younger brother, but as a colleague who is wearing her patience thin. She has no hang-ups about announcing that Neil cheated to gain the position he’s in or insulting him right to his face. Mulder and Scully, these two aint, only because the Mulder here is an absolute cretin. Is Neil intended to be the comic relief? He certainly isn’t the rock of the protagonist duo keeping things together, so I suppose the developers intended to be the sportive source in a game revolving around heavy subject matter. Still, there isn’t anything funny about constant pop culture references or acting like an immature child when prompted to perform the most menial of tasks. Neil strays too far with his clown persona that it creates tone issues for To the Moon.

I was fully ready to rant about how To the Moon did not deliver on its promise of an emotionally impactful experience all because of Neil’s shenanigans until the end when the game managed to save itself. Reaching back into John’s earliest memories at a carnival where he meets River for the first time as a little child. When River expresses curiosity about the stars and the moon when she’s gazing up at the night sky with John, an alarming realization hits our protagonists like a ton of bricks. The reason why they’ve been having difficulties directing John towards his dying wish is that it was never his wish to begin with: it was River’s final wish that he was fulfilling for her. When our protagonists finally understand John’s motive, a conflict in ethics arises in the decision to erase River from John’s memory. By some miracle, I found myself agreeing with Neil’s stance to let things be and leave the misguided man’s memories alone, while Eva continues to press that it should be done for the sake of the mission like a cold-hearted bureaucrat. I couldn’t believe I was siding with the fuckhead that had been pissing me off to no end for the past few hours, as I shared his devastation when River had vanished from John’s high school days in the blink of an eye. Because John never went on that first date with River, this leads him through a “George Constanza abstinence directive” where he focuses on his studies to become an astronaut now that the possibility of having sex is gone. Once he succeeds and NASA gives him a grand tour of their facility, another recruit named River is there to join him on their mission to tour the moon. Also, this time alteration saves his brother, Joey, somehow. In the ideal timeline that Eva created, he marries his true love after their time spent living their wildest dreams. However, the player does not witness their moon expedition firsthand, for John in the real world flat lines and fades to black. John is buried alongside River next to the lighthouse, and Neil and Eva are given another call for a new patient. By the skin of its teeth, To the Moon yanks out an ending that sincerely tugged at my heartstrings.

I’m not going to be okay for a while now, and To the Moon is to blame. For the longest time while playing To the Moon, I was skeptical of its potency to turn on the waterworks as I had anticipated. Sure, the inherent plot of the game was sad enough to support it initially, but the impact became muddled in too much quippy dialogue from a certain character who almost ruined it entirely. With great patience, I pulled through and experienced the game pulling a buzzer-beater of an ending that made me forget about all that annoyed me beforehand, climaxing the intricate story superbly in something effectively heartwarming. Are the game’s characters a lot to be desired? Without a doubt. Is the gameplay so simple that a chimpanzee could do it? Absolutely. Is everything wrapped up in a package that is perhaps a little too contrived and convenient? You betcha. Still, the gaming medium needs games like To the Moon to prove its narrative potential.

...

While I'm at it, the story here is better than Inception. There's your hot take for the day.

------

Attribution:// https://erockreviews.blogspot.com

Already, the plot premise of To the Moon should slightly moisten the player’s eyes. An old man named John Wyles is lying on his deathbed, and his last wish before he passes into the eternal ether mirrors the fantasies expressed in early 20th-century cinema: a trip to the moon. Even in the fictitious realm of video games, there is no Make-A-Wish foundation for privileged senior citizens to fulfill such fanciful dying desires that only a handful of people on Earth have ever experienced. However, an organization called Sigmund Corp. can work around the expenses and general feasibility of this grand request by planting artificial experiences into the patient’s brain as they lie there comatose. Two doctors appointed by Sigmund Corp named Neil Watts and Eva Rosaline are on call to execute the mission by visiting John’s mansion and applying an apparatus to him while he lies in bed. Integrating these fake memories into John’s fading consciousness is quite the ordeal, so Neil and Eva must brew some coffee for the all-nighter they are about to undergo. As we speak, there should be at least a few choked-up throats upon reading what To the Moon’s narrative has to offer. The concept of death is an uncomfortable, bittersweet topic that will constantly nag us with feelings of dread throughout our time on Earth. The concept of death and dying is arguably the most universal human fear that crosses all cultural boundaries, even if the scattered earth civilizations have their interpretations of the inevitable. Because death and its implications are such a prevalent force while we are living, we do not need any context as to who John was as a human being to empathize with his critical condition.

To the Moon’s premise hardly sounds like something a triple-A studio would produce, so expect the game’s presentation to display the minimalistic trappings of an indie studio. Specifically, To the Moon was developed with RPG Maker, a computer program downloadable by the general public to craft their own RPG games. To the Moon isn’t working with a modest sum of resources: it’s something any schmuck with Windows 7 could’ve conjured up in one afternoon. In all fairness, despite how cheap and unprofessional the base software of To the Moon’s development sounds, the final product could still ultimately prove substantial if the developers know how to work around the constraints of a pail bucket budget. Besides, I’ve always stated that any modern game rendered in the pixelated past of the medium always possesses an endearing quality, and To the Moon is no exception. With the pixelated format the game works with, To the Moon’s graphics strike a balance between cherubic and sublime. The chibi characters in the foreground contrast with the often picturesque displays of the backgrounds. Look at the sight of the nearby lighthouse peaking over the cliffside where John’s mansion is located and you’ll understand the visual dichotomy I’m attempting to illustrate. It’s beautiful but carries a sense of melancholy. Like most indie titles from the 21st century that use pixels as a driving force of their artistic direction, To the Moon still looks crisper and cleaner than what the big boys of the industry were working on in the later years of the previous century. It’s telling how far the medium has progressed when a program as accessible as this one outperforms anything made with an enormous budget only two decades prior.

Despite the name of the software that To the Moon was created in, the game is not an RPG of any sort. Our two protagonists fight a squirrel on the rocky road up to John’s house in a turn-based format, but this is a one-time snarky, ironic joke to throw off the expected precedent. No, the developers figured the tasteful way to gamify a story where an old man meets his timely demise is to render it into a point-and-click adventure title. With the conjoined Inception-esque apparatus, Neil and Eva can fully access every memory and experience from John’s storied life, or at least how John recalls them. Their objective is to redirect the course of John’s life through their minor alterations, simply by subtly or unsubtly passing the idea to visit the moon while he still had time. Neil and Eva know that timeliness is essential considering the host of the simulation could perish at any moment, so their first attempt is to grab him a few months before he’s bedridden to relay the idea. Unfortunately for them, John’s twilight years were rather occupied with other worries, such as aiding his dearly departed wife River when she was in hospice and how to feasibly move a grand piano up and down a flight of stairs. John is too long in the tooth to be considering the improbable goal of space travel, so Neil and Eva are forced to delve further into John’s past to find him at a more impressionable age. The rewinding process through John’s life is how the game implements the interactive point-and-click elements. To dig deeper into the strata of John’s life, Neil and Eva must find a memento whose resonance will serve as a portal to an earlier memory. Commonly used mementos include a bag that John carried around and a stuffed platypus plush owned by River. To activate the memento, Neil and Eva must find five pieces of contextual evidence behind the memento found in the same scene, usually after the conversational section between John and another person is finished. Oftentimes, the substance behind the gameplay in a point-and-click adventure is solving puzzles to progress, giving the player a hint of interactivity that will keep them engaged. To the Moon offers something in the same vein, but it's far too elementary. The five pieces of context needed for the memento are hidden in plain sight, and the area where they are all located is confined enough that finding all of them will most likely take a few minutes at most. When the five pieces are all assembled at the chosen memento, the player is transported to a puzzle section where they must align a picture by a 5X5 grid. This simple task will also prove to be quick and easy, as there is no time limit and no penalties for accidentally making the image less coherent. I always worry when narrative-focused video games sacrifice gameplay to fortify the story, and To the Moon is another example that will continue this concern.

Alright, so if To the Moon’s gameplay is effortless so as to not distract from the foreground of the narrative, certainly the game compensates with solid characters that drive the story’s intrigue. John, for example, has circled around the sun enough times to have experienced plenty of amazement and hardships, so traveling down the rabbit hole that is his entire life should ideally be interesting, right? Actually, John’s life is realistically mundane. In fact, the man led a pretty insular life with the same people. He married his high school girlfriend, proceeded to stay acquainted with his best friend Nick into adulthood, and has been kept company by his caretaker Lily, and her two children after his wife passed into old age. Upon exploring John’s past, it seems as if his wife, River, is the fascinating one by comparison as we learn about her diagnosis of Asperger's and how it correlates to why she obsessively makes origami bunnies that are strewn all over John’s basement. We never know what John’s former occupation was and how he could afford a countryside estate that overlooks a lighthouse. Whatever it was, I’m sure it was incredibly boring. It isn’t until Neil and Eva have to connect the bridge of John’s past to his early childhood that we discover that John’s existence hasn’t always been so spotless. For some reason, the time before John’s teenage years is obscured in a hazy shield of blankness, for his time-consuming beta blockers in the military (which is only explained through exposition and not experienced firsthand) have blocked it from view. After forcibly pushing past the impediment, we learn that John is suffering the trauma of losing his twin brother Joey in a pedestrian car accident when they were still in grade school. To retain some semblance of Joey’s presence on this earth, John subconsciously adopted all of his quirks such as his adoration for pickled olives. He also gained Joey’s fondness for the Animorphs books series, which means that this old geezer is a decrepit millennial, and the modern-day in this game is in the later decades of the 21st century. Thanks for making your target demographic (me) fret over their mortality, guys. Uncovering the pinnacle turning point in John’s life that shaped his present-day demeanor suddenly makes us invested in him and adds some spice to the humdrum future events we’ve already witnessed.

Where To the Moon has characters who have the personalities of a wet sock, the game also features those on the other end of the spectrum who are a bit much. Neil Watts, the male half of the Sigmund Corp duo, is…how do I put this nicely? He’s a real prick. He’s impatient, obnoxious, rude, and treats the job he’s doing with such callousness that it is practically offensive. In sensitive fields such as the one he specializes in, it’s understood that one has to harden their heart to deal with the heaviness of death. Still, Neil presents himself with such aloofness that he comes off as a clod. The game is somewhat aware of Neil’s flawed personality through his dynamic with Eva, the straight (wo)man on the job. She constantly reprimands Neil for his buffoonery not playfully as a couple with brewing sexual tension or as a younger brother, but as a colleague who is wearing her patience thin. She has no hang-ups about announcing that Neil cheated to gain the position he’s in or insulting him right to his face. Mulder and Scully, these two aint, only because the Mulder here is an absolute cretin. Is Neil intended to be the comic relief? He certainly isn’t the rock of the protagonist duo keeping things together, so I suppose the developers intended to be the sportive source in a game revolving around heavy subject matter. Still, there isn’t anything funny about constant pop culture references or acting like an immature child when prompted to perform the most menial of tasks. Neil strays too far with his clown persona that it creates tone issues for To the Moon.

I was fully ready to rant about how To the Moon did not deliver on its promise of an emotionally impactful experience all because of Neil’s shenanigans until the end when the game managed to save itself. Reaching back into John’s earliest memories at a carnival where he meets River for the first time as a little child. When River expresses curiosity about the stars and the moon when she’s gazing up at the night sky with John, an alarming realization hits our protagonists like a ton of bricks. The reason why they’ve been having difficulties directing John towards his dying wish is that it was never his wish to begin with: it was River’s final wish that he was fulfilling for her. When our protagonists finally understand John’s motive, a conflict in ethics arises in the decision to erase River from John’s memory. By some miracle, I found myself agreeing with Neil’s stance to let things be and leave the misguided man’s memories alone, while Eva continues to press that it should be done for the sake of the mission like a cold-hearted bureaucrat. I couldn’t believe I was siding with the fuckhead that had been pissing me off to no end for the past few hours, as I shared his devastation when River had vanished from John’s high school days in the blink of an eye. Because John never went on that first date with River, this leads him through a “George Constanza abstinence directive” where he focuses on his studies to become an astronaut now that the possibility of having sex is gone. Once he succeeds and NASA gives him a grand tour of their facility, another recruit named River is there to join him on their mission to tour the moon. Also, this time alteration saves his brother, Joey, somehow. In the ideal timeline that Eva created, he marries his true love after their time spent living their wildest dreams. However, the player does not witness their moon expedition firsthand, for John in the real world flat lines and fades to black. John is buried alongside River next to the lighthouse, and Neil and Eva are given another call for a new patient. By the skin of its teeth, To the Moon yanks out an ending that sincerely tugged at my heartstrings.

I’m not going to be okay for a while now, and To the Moon is to blame. For the longest time while playing To the Moon, I was skeptical of its potency to turn on the waterworks as I had anticipated. Sure, the inherent plot of the game was sad enough to support it initially, but the impact became muddled in too much quippy dialogue from a certain character who almost ruined it entirely. With great patience, I pulled through and experienced the game pulling a buzzer-beater of an ending that made me forget about all that annoyed me beforehand, climaxing the intricate story superbly in something effectively heartwarming. Are the game’s characters a lot to be desired? Without a doubt. Is the gameplay so simple that a chimpanzee could do it? Absolutely. Is everything wrapped up in a package that is perhaps a little too contrived and convenient? You betcha. Still, the gaming medium needs games like To the Moon to prove its narrative potential.

...

While I'm at it, the story here is better than Inception. There's your hot take for the day.

------

Attribution:// https://erockreviews.blogspot.com