ItalianRobo

5 reviews liked by ItalianRobo

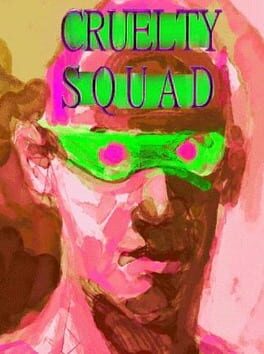

Cruelty Squad

2021

It's easy to take a glance at Cruelty Squad's unpleasant artstyle and dismiss it for being obvious and unsubtle about its intent, when most of critical praise seemingly rests on its ability to create a playable shitpost deep fried meme that bluntly satirizes the sewer corporate modern age we live in and not much else inbetween. That however would be understating the talent and craft that is required to make such effective "heavy handed" art like Cruelty Squad.

Baffling to realize that this was Ville Kallio's first shot at videogames, because he displays such a strong understanding of the medium and utilizes so much of its strengths in ways that no other developers have really tapped into to create what I can only describe as a arthouse masterpiece of counter intuitive art and game design. Our infactuation with cyberpunk dystopia has created such pleasing worlds to look at in all of fiction that the only thing Cruelty Squad had to do was present the existential nightmare we already live in it its true colors. Making a house the most expensive item that gates you from the rest of the game's content might come across as portentous hassle for the player and an easy cheap jab at Capitalism™, but it doesn't make its statement any less truer and effective.

Getting accustomed to Cruelty Squad vomit inducing textures ends up becoming an inevitability, and the game beneath it surprisingly reveals enough enticing complexity and kinesthetic gratification that will distract you from the uglyness of it all. DNA taken straight out of Quake make traversal in Cruelty Squad's industrial purgatory oddly satisfying and addicting to exploit as you discover there is fun in retrying missions to find new secrets in the open ended maze like levels and speedunning CEO and landlord assassinations, raking in the dough to invest and buy more expensive game changing implants that further blur the line between man and biomachine monstrosity. Sooner than expected, you end up forgetting the garish mismatched colors and low poly disorienting textures that assault your senses, and Cruelty Squad ends up becoming just another game to master like all the others that came before it.

Were this any other game, I would be taking down a couple of points for it losing its luster after the initial hours, but Cruelty Squad losing its repulsiveness over time just ends up reinforcing its message that much more. In the same way that Cruelty Squad visualizes what violent videogames must look like to our parents, it displays for a brief moment the reality and future humanity has devised for itself, as if putting on the They Live glasses for the first time. But eventually we get used to it. And we forget, we comply, we find pleasure in it. Luckily we get the chance once in a while to experience something like Cruelty Squad to remind us that we are all just meat sacks ticking up and down on a graph, selling ourselves short to the highest bidder.

PS: The easiest method I found out to make quick money in Cruelty Squad was to kill Elon Musk's personification over and over again and betting on the stock market right after. Something very poignant and cathartic about that. Don't tank my crypto next time, asshole.

Baffling to realize that this was Ville Kallio's first shot at videogames, because he displays such a strong understanding of the medium and utilizes so much of its strengths in ways that no other developers have really tapped into to create what I can only describe as a arthouse masterpiece of counter intuitive art and game design. Our infactuation with cyberpunk dystopia has created such pleasing worlds to look at in all of fiction that the only thing Cruelty Squad had to do was present the existential nightmare we already live in it its true colors. Making a house the most expensive item that gates you from the rest of the game's content might come across as portentous hassle for the player and an easy cheap jab at Capitalism™, but it doesn't make its statement any less truer and effective.

Getting accustomed to Cruelty Squad vomit inducing textures ends up becoming an inevitability, and the game beneath it surprisingly reveals enough enticing complexity and kinesthetic gratification that will distract you from the uglyness of it all. DNA taken straight out of Quake make traversal in Cruelty Squad's industrial purgatory oddly satisfying and addicting to exploit as you discover there is fun in retrying missions to find new secrets in the open ended maze like levels and speedunning CEO and landlord assassinations, raking in the dough to invest and buy more expensive game changing implants that further blur the line between man and biomachine monstrosity. Sooner than expected, you end up forgetting the garish mismatched colors and low poly disorienting textures that assault your senses, and Cruelty Squad ends up becoming just another game to master like all the others that came before it.

Were this any other game, I would be taking down a couple of points for it losing its luster after the initial hours, but Cruelty Squad losing its repulsiveness over time just ends up reinforcing its message that much more. In the same way that Cruelty Squad visualizes what violent videogames must look like to our parents, it displays for a brief moment the reality and future humanity has devised for itself, as if putting on the They Live glasses for the first time. But eventually we get used to it. And we forget, we comply, we find pleasure in it. Luckily we get the chance once in a while to experience something like Cruelty Squad to remind us that we are all just meat sacks ticking up and down on a graph, selling ourselves short to the highest bidder.

PS: The easiest method I found out to make quick money in Cruelty Squad was to kill Elon Musk's personification over and over again and betting on the stock market right after. Something very poignant and cathartic about that. Don't tank my crypto next time, asshole.

Firewatch

2016

This review contains spoilers

Real life isn't satisfying. Going out into the woods for an entire summer doesn't mean all of your personal woes automatically get solved. Obsessively pursuing what you perceive to be a conspiracy against yourself doesn't mean you get a neatly-wrapped conclusion. Fires don't wipe the land perfectly clean, but instead leave suffocating ash and smoke in their wake. Going out of your way to fix a particular problem more often than not just leaves you with more. This is a theme that I could see being adapted brilliantly as a video game, but the problem is that Firewatch doesn't try to emulate real life, instead it tries its hardest to be a movie. Beyond just being a walking simulator about the great outdoors where you're pretty much only allowed to traverse man-made paths, the game skips through all of the "uninteresting" parts of your job as a lookout to make sure something important's happening at all times. It's so sanitized, so free of anything that's slightly inconvenient or boring, that you really can't call it anything but satisfying, and therefore can't call it anything but a failure at getting its point across as a video game. I'll fully admit that my rating here is entirely for the concept and atmosphere. It puts the barest amount of effort in and still manages to be unnerving, which is why it's so frustrating. It really seems like these guys wanted to make a movie, and they should have! But then again, if they did, they probably would've had to rewrite Delilah to be a real person with a real personality instead of just another endless dispensary of sarcastic quips. Probably not worth the effort.

Papers, Please

2013

It's an absolutely perfect adaptation to game mechanics from something that isn't a game. First you're taking your time, looking up everything in the guidebook to make sure you make no mistakes. Then you're strategizing about which rule checks are worth skipping because they take too long to warrant worrying about the fine they might cost you. Before you know it, it's second nature. You know that Bostan is in Republia and that the line on the MOA emblem goes diagonally from bottom left to top right. On top of this, the game is so good at increasing its complexity- each new rule fits in flawlessly with the existing mechanics, with the difficulty curve, and with the story events.

Like any great game, it feels worth mastering, but it by no means stops there, because you're in Arstotzka, a world where you're never commended for doing anything correctly, only reprimanded for doing things incorrectly. A world where you're fined heavily for the act of decorating your workspace. A world where conducting an X-ray to verify someone's sex and seizing someone's passport without any real justification aren't gross violations of rights but simply burdens, items on a checklist that must be done. Ultimately, Papers, Please is about being molded into thinking, acting, and making decisions like a robot. Come across a moral dilemma and you'll more than likely make your choice on whether or not to admit someone just based on if you've exceeded your protocol violation warning limit for the day. Human beings aren't human beings in Arstotzka, they're means to an end. Through this theme, not only does the game perfectly encapsulate both bureaucratic labor and authoritarian government as a whole, but it comes to the conclusion that no other game with moral dilemmas has been able to quite reach. When working as an immigration officer, there are no people. There are only sets of information which may or may not line up, the specific details of which are so irrelevant towards whether or not someone deserves to pass that they might as well be randomly generated.

And yet, somehow, the human side of Arstotzka shines through. Jorji is more than fine with playing the immigration game, applauding you for working such a difficult job whenever he's denied entry and vying to have more convincing papers next time. Calensk tells you that you'll earn a bonus for detaining more people, and yet he's unable to pay you fully the first few times because he had to spend more money taking care of his family than he anticipated. Even Dimitri, the man in charge of overseeing your position, the man who's forced you to become this robot, will give you a game over if you follow protocol and refuse to let one of his friends into the country. Like the rest of the game, this characterization is so effortlessly natural. The game's mechanics already made going back to get all the medals and endings worthwhile, but picking up on these details adds an additional, equally fulfilling layer. This all culminates in what I think is the high point of the entire game, and what's probably the most optimistic of the major endings. You've just grinded out nearly two-hundred credits to escape the country and are now at the hands Obristan's immigration officer with your family. But you're not denied entry, like you so very much deserve to be, you're let in. Why? Maybe the officer didn't notice your passports were forged, or maybe he inferred the situation that you were in and took mercy. Either way, it's because he's a human being, not a robot, and now your family's safe. Thanks for playing, roll credits.

Like any great game, it feels worth mastering, but it by no means stops there, because you're in Arstotzka, a world where you're never commended for doing anything correctly, only reprimanded for doing things incorrectly. A world where you're fined heavily for the act of decorating your workspace. A world where conducting an X-ray to verify someone's sex and seizing someone's passport without any real justification aren't gross violations of rights but simply burdens, items on a checklist that must be done. Ultimately, Papers, Please is about being molded into thinking, acting, and making decisions like a robot. Come across a moral dilemma and you'll more than likely make your choice on whether or not to admit someone just based on if you've exceeded your protocol violation warning limit for the day. Human beings aren't human beings in Arstotzka, they're means to an end. Through this theme, not only does the game perfectly encapsulate both bureaucratic labor and authoritarian government as a whole, but it comes to the conclusion that no other game with moral dilemmas has been able to quite reach. When working as an immigration officer, there are no people. There are only sets of information which may or may not line up, the specific details of which are so irrelevant towards whether or not someone deserves to pass that they might as well be randomly generated.

And yet, somehow, the human side of Arstotzka shines through. Jorji is more than fine with playing the immigration game, applauding you for working such a difficult job whenever he's denied entry and vying to have more convincing papers next time. Calensk tells you that you'll earn a bonus for detaining more people, and yet he's unable to pay you fully the first few times because he had to spend more money taking care of his family than he anticipated. Even Dimitri, the man in charge of overseeing your position, the man who's forced you to become this robot, will give you a game over if you follow protocol and refuse to let one of his friends into the country. Like the rest of the game, this characterization is so effortlessly natural. The game's mechanics already made going back to get all the medals and endings worthwhile, but picking up on these details adds an additional, equally fulfilling layer. This all culminates in what I think is the high point of the entire game, and what's probably the most optimistic of the major endings. You've just grinded out nearly two-hundred credits to escape the country and are now at the hands Obristan's immigration officer with your family. But you're not denied entry, like you so very much deserve to be, you're let in. Why? Maybe the officer didn't notice your passports were forged, or maybe he inferred the situation that you were in and took mercy. Either way, it's because he's a human being, not a robot, and now your family's safe. Thanks for playing, roll credits.

Papers, Please

2013

Papers, Please has the aesthetic subtly of a brick, which may distract you from the dynamic subtly of actual gameplay.

If you do well, Papers, Please allows you to flow really deeply into a state of focused play. Efficient movement, checking, interactions, etc. make it very easy to ignore the people and focus on the papers, and become a contented cog in the dystopian machine. You may even feel frustration with people, especially when the reason stamp pops up, who make you break out of this loop because you need to interrogate them. Yes, you get more money if you're a good cog, that's a mechanical reward, but being a good cog also lets you have more fun, because it lets you perfect the gameplay loop the game presents to you.

Papers, Please doesn't narratively reward your emotions for being a dystopia cog, but it does ludically reward your emotions for being a cog. That's some interesting dissonance to have going on.

If you do well, Papers, Please allows you to flow really deeply into a state of focused play. Efficient movement, checking, interactions, etc. make it very easy to ignore the people and focus on the papers, and become a contented cog in the dystopian machine. You may even feel frustration with people, especially when the reason stamp pops up, who make you break out of this loop because you need to interrogate them. Yes, you get more money if you're a good cog, that's a mechanical reward, but being a good cog also lets you have more fun, because it lets you perfect the gameplay loop the game presents to you.

Papers, Please doesn't narratively reward your emotions for being a dystopia cog, but it does ludically reward your emotions for being a cog. That's some interesting dissonance to have going on.