PasokonDeacon

1985

Or, as my backronym addled brain would tell me: Truly Hard, Early eXceptional DOS-era Evil Robodungeon. 1 mecha, 2 transformations, 15 complex levels, and infinite loops. Better start jetting and blasting.

Thexder was to PC-88 what Super Mario Bros. was to NES. Game Arts hit the motherlode when releasing their debut, a PC-88 action dungeon-crawler modeled after Atari's vector game Major Havoc. 1985 saw a major upswing in adoption of the PC-88, then NEC's beefiest 8-bit home computer. (Hey, guess which platform isn't associated with Thexder on IGDB yet? That's right, the one it was originally made for! Go team! /seething) With a new upgraded model on the horizon, these ex-ASCII programmers formed Game Arts with hopes of making an arcade classic for the home player. Hibiki Godai and Satoshi Uesaka's final game ended up becoming the PC-88's killer app, selling the faster mkIISR models in droves.

Suffice to say, both Square and Sierra On-Line were impressed enough to make their own ports, the former to MSX and Famicom while the latter brought Thexder overseas to IBM-compatible PCs. The DOS port thankfully rebalances the often harsh difficulty of the original. You take less damage and have an easier time collecting health & power-ups, that's for sure. While Thexder '85 is quite fun and beatable, it's also as brutal as you'd expect for an early foray into multi-stage mecha action with stats and memorization. Game Arts clearly wanted their players to clear at least the first loop, but it's tough going until you know some secrets and enemy patterns. I've beaten the DOS version a couple times now, so try that first if you want a faithful but accessible experience.

The whole appeal of Thexder comes from its mech-to-plane dynamics, where you swap between forms to use either the former's auto-targeting laser or the latter's speed and smaller size. Both modes let you navigate each techno-industrial maze while eliminating hordes of varied enemies, plus nabbing repair pick-ups along the way. Early stages ease you into the mechanics about as well as Nintendo's own games from the time, all before changing scenery and heading into caves full of nastiness. I always get a palpable sense of "where the hell is this mission taking me?" the closer I get to the end, even knowing the few boss encounters due to arrive. Having to weigh tradeoffs between your forms, plus carefully proceeding through hazardous areas you may or may not know, adds a satisfying tension to Game Arts' labyrinths. It may be a ruthless one to start with, but clearing it remains fulfilling, like defeating the Tower of Druaga which players would have been familiar with at the time.

It's awesome to see how effectively the team adapted Major Havoc into a richer adventure. The evolution from 1984's few screens' worth of level design, to Thexder having 4x that amount a level on average…games were improving so damn fast in that era. What might seem quaint or downright hostile was innovative back then, and shows its cleverness even today.

With a catchy musical theme and colorful, fluid scrolling visuals at a time when the PC-88 lent itself best to static adventure and sim./strategy titles, Thexder stood out. It proved that talented developers could squeeze anything out of NEC's hobbyist system, from intense arcade-style titles like this to more elaborate sagas like Ys or Uncharted Waters. And it gave new system owners the meaty, multi-playthrough software they needed at a time when Nintendo's Famicom and the arcades were far eclipsing Japanese PC games in immediate appeal. The era of simplistic, monochrome PC-8001 games was out; the FM-synth wielding, level-scrolling PC-88 releases were coming hard and fast. Game Arts led the charge with Thexder, Cuby Panic, and Silpheed, all of which earned their classic status in the midst of the J-PC gaming golden age.

Thexder was to PC-88 what Super Mario Bros. was to NES. Game Arts hit the motherlode when releasing their debut, a PC-88 action dungeon-crawler modeled after Atari's vector game Major Havoc. 1985 saw a major upswing in adoption of the PC-88, then NEC's beefiest 8-bit home computer. (Hey, guess which platform isn't associated with Thexder on IGDB yet? That's right, the one it was originally made for! Go team! /seething) With a new upgraded model on the horizon, these ex-ASCII programmers formed Game Arts with hopes of making an arcade classic for the home player. Hibiki Godai and Satoshi Uesaka's final game ended up becoming the PC-88's killer app, selling the faster mkIISR models in droves.

Suffice to say, both Square and Sierra On-Line were impressed enough to make their own ports, the former to MSX and Famicom while the latter brought Thexder overseas to IBM-compatible PCs. The DOS port thankfully rebalances the often harsh difficulty of the original. You take less damage and have an easier time collecting health & power-ups, that's for sure. While Thexder '85 is quite fun and beatable, it's also as brutal as you'd expect for an early foray into multi-stage mecha action with stats and memorization. Game Arts clearly wanted their players to clear at least the first loop, but it's tough going until you know some secrets and enemy patterns. I've beaten the DOS version a couple times now, so try that first if you want a faithful but accessible experience.

The whole appeal of Thexder comes from its mech-to-plane dynamics, where you swap between forms to use either the former's auto-targeting laser or the latter's speed and smaller size. Both modes let you navigate each techno-industrial maze while eliminating hordes of varied enemies, plus nabbing repair pick-ups along the way. Early stages ease you into the mechanics about as well as Nintendo's own games from the time, all before changing scenery and heading into caves full of nastiness. I always get a palpable sense of "where the hell is this mission taking me?" the closer I get to the end, even knowing the few boss encounters due to arrive. Having to weigh tradeoffs between your forms, plus carefully proceeding through hazardous areas you may or may not know, adds a satisfying tension to Game Arts' labyrinths. It may be a ruthless one to start with, but clearing it remains fulfilling, like defeating the Tower of Druaga which players would have been familiar with at the time.

It's awesome to see how effectively the team adapted Major Havoc into a richer adventure. The evolution from 1984's few screens' worth of level design, to Thexder having 4x that amount a level on average…games were improving so damn fast in that era. What might seem quaint or downright hostile was innovative back then, and shows its cleverness even today.

With a catchy musical theme and colorful, fluid scrolling visuals at a time when the PC-88 lent itself best to static adventure and sim./strategy titles, Thexder stood out. It proved that talented developers could squeeze anything out of NEC's hobbyist system, from intense arcade-style titles like this to more elaborate sagas like Ys or Uncharted Waters. And it gave new system owners the meaty, multi-playthrough software they needed at a time when Nintendo's Famicom and the arcades were far eclipsing Japanese PC games in immediate appeal. The era of simplistic, monochrome PC-8001 games was out; the FM-synth wielding, level-scrolling PC-88 releases were coming hard and fast. Game Arts led the charge with Thexder, Cuby Panic, and Silpheed, all of which earned their classic status in the midst of the J-PC gaming golden age.

1979

As said by a wise old sage: "be rootin', be tootin', and by Kong be shootin'...but most of all, be kind."

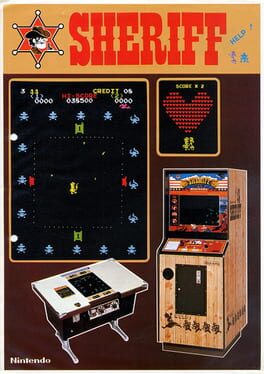

Everyone remembered the OK Corral differently. The Earps and feuding families each had their self-serving accounts of the shootout. John Ford, Stuart Lake, and other myth-makers turned the participants into legends, models of masculinity, freedom-seekers, and a long-lost Old West But the truth's rarely so glamorous or controversial. Just as the OK Corral gunfight never took place in the corral itself, Nintendo's Sheriff was never just the handiwork of a newly-hired Shigeru Miyamoto. How vexing it is that the echoes of Western mythologizing reach this far!

I am exaggerating a bit with regards to how Nintendo fans & gamers at large view this game. Miyamoto's almost always discussed in relation to Sheriff as an artist & assistant designer, not the producer (that'll be Genyo Takeda, later of StarTropics fame). That's not to diminish what the famous creator did contribute. While Nintendo largely put out clones and what I'd charitably call "experiments" by this point, their '79 twin-stick shooter defies that trend. It's still a bit rough-hewn, like any old cowboy, yet very fun and replayable.

Compared to earlier efforts like Western Gun & Boot Hill, there's more creative bending of Wild West stereotypes here, to mixed results. Though not the first major arcade game with an intermission, the scenes here are cute, a sign that the Not Yet Very Big N's developers were quick to match their competition. I do take umbrage with translating Space Invaders' aliens to bandits, though. Sure, this long predates modern discussions about negative stereotyping in games media, but that hardly disqualifies it. Let's just say that this game's rather unkind to its characters, from the doofy-looking lawman to his blatant damsel-in-distress & beyond. Respect to the condor, though. That's some gumption, flying above the fray on this baleful night, just askin' fer a plummet.

The brilliant part here is giving you solid twin-stick controls for moving & shooting well ahead of Midway's Robotron 2084. The dim bit is those enemy bullets, slow as molasses and firing only in cardinal directions. Normally you or the operator could just flip a DIP switch to raise the difficulty, but those options are absent too. What results is a fun, but relatively easy take on the Invaders template, one which rewards you a bit too much prior to developing the skills encouraged in Taito's originals. For example, it's much easier to aggressively fire here than to take cover, given the easily ignorable shields & posts. Your dexterity here compared to Space Invaders, or even Galaxian, tends to outweigh your opponents, for better and worse.

A counter-example comes when a few bandits charge into the corral, able to lunge at you if you trot too close. This spike in danger is exciting, an alternative to Galaxian's waves system which similarly revolutionizes your play-space. Where once you could just snipe at leisure, now you have to keep distance or get stabbed in the back! Of course, ranged exchanges were all that happened at the OK Corral. A little artistic liberty playing up the tropes can work out after all. Perhaps our strapping Roy Rogers believes in good 'ol fashioned marksmanship; he's a fool to deny himself fisticuffs, but a brave one.

When I'm not gunning down the circle of knives or playing matador with them, I think about how simple but compelling the game's premise is. We've gone from one Wild West tropset (the Mexican standoffs seen in Gunman & its ilk) to another, more politically charged one. You may be a lone marshall, but not much more than a deputized gang shooter. The game inadvertently conveys a message of liquid morality & primacy of who's more immediately anthropomorphic—empowering the Stetson hat over the sombrero. All basic American History 101 stuff, but displayed this vividly, this blatantly in a game this early? This seems less so Miyamoto's charm, more so his accidental wit.

Life's just too easy for the Wyatt Earps of this fictionalized, simplistic world. Another round in the corral, another kiss in the saloon, rinse and repeat. Maybe I'm giving too much credit to a one-and-done go at complexifying the paradigm Taito started, but it's filling food for thought. I highly recommend at least trying Sheriff today just to experience its odd thrills & ersatz yet perceptive view of the corral shootout tradition. The Fords & Miyamotos of the world, working with film & video games in their infancy, had a knack for making the most of limited possibilities. For all my misgivings, the distorted tales of the Old West are ample fodder for a destructive ride on the joysticks. Sheriff's team would go on to make works as iconic as Donkey Kong, so why downplay their earliest attempts to work with material as iconic as this?

I'm sure Sheriff will came back 'round these parts, like a tumbleweed hops from Hollywood ghost towns to the raster screen. Don't lemme see ya causin' trouble in The Old MAME, son.

Everyone remembered the OK Corral differently. The Earps and feuding families each had their self-serving accounts of the shootout. John Ford, Stuart Lake, and other myth-makers turned the participants into legends, models of masculinity, freedom-seekers, and a long-lost Old West But the truth's rarely so glamorous or controversial. Just as the OK Corral gunfight never took place in the corral itself, Nintendo's Sheriff was never just the handiwork of a newly-hired Shigeru Miyamoto. How vexing it is that the echoes of Western mythologizing reach this far!

I am exaggerating a bit with regards to how Nintendo fans & gamers at large view this game. Miyamoto's almost always discussed in relation to Sheriff as an artist & assistant designer, not the producer (that'll be Genyo Takeda, later of StarTropics fame). That's not to diminish what the famous creator did contribute. While Nintendo largely put out clones and what I'd charitably call "experiments" by this point, their '79 twin-stick shooter defies that trend. It's still a bit rough-hewn, like any old cowboy, yet very fun and replayable.

Compared to earlier efforts like Western Gun & Boot Hill, there's more creative bending of Wild West stereotypes here, to mixed results. Though not the first major arcade game with an intermission, the scenes here are cute, a sign that the Not Yet Very Big N's developers were quick to match their competition. I do take umbrage with translating Space Invaders' aliens to bandits, though. Sure, this long predates modern discussions about negative stereotyping in games media, but that hardly disqualifies it. Let's just say that this game's rather unkind to its characters, from the doofy-looking lawman to his blatant damsel-in-distress & beyond. Respect to the condor, though. That's some gumption, flying above the fray on this baleful night, just askin' fer a plummet.

The brilliant part here is giving you solid twin-stick controls for moving & shooting well ahead of Midway's Robotron 2084. The dim bit is those enemy bullets, slow as molasses and firing only in cardinal directions. Normally you or the operator could just flip a DIP switch to raise the difficulty, but those options are absent too. What results is a fun, but relatively easy take on the Invaders template, one which rewards you a bit too much prior to developing the skills encouraged in Taito's originals. For example, it's much easier to aggressively fire here than to take cover, given the easily ignorable shields & posts. Your dexterity here compared to Space Invaders, or even Galaxian, tends to outweigh your opponents, for better and worse.

A counter-example comes when a few bandits charge into the corral, able to lunge at you if you trot too close. This spike in danger is exciting, an alternative to Galaxian's waves system which similarly revolutionizes your play-space. Where once you could just snipe at leisure, now you have to keep distance or get stabbed in the back! Of course, ranged exchanges were all that happened at the OK Corral. A little artistic liberty playing up the tropes can work out after all. Perhaps our strapping Roy Rogers believes in good 'ol fashioned marksmanship; he's a fool to deny himself fisticuffs, but a brave one.

When I'm not gunning down the circle of knives or playing matador with them, I think about how simple but compelling the game's premise is. We've gone from one Wild West tropset (the Mexican standoffs seen in Gunman & its ilk) to another, more politically charged one. You may be a lone marshall, but not much more than a deputized gang shooter. The game inadvertently conveys a message of liquid morality & primacy of who's more immediately anthropomorphic—empowering the Stetson hat over the sombrero. All basic American History 101 stuff, but displayed this vividly, this blatantly in a game this early? This seems less so Miyamoto's charm, more so his accidental wit.

Life's just too easy for the Wyatt Earps of this fictionalized, simplistic world. Another round in the corral, another kiss in the saloon, rinse and repeat. Maybe I'm giving too much credit to a one-and-done go at complexifying the paradigm Taito started, but it's filling food for thought. I highly recommend at least trying Sheriff today just to experience its odd thrills & ersatz yet perceptive view of the corral shootout tradition. The Fords & Miyamotos of the world, working with film & video games in their infancy, had a knack for making the most of limited possibilities. For all my misgivings, the distorted tales of the Old West are ample fodder for a destructive ride on the joysticks. Sheriff's team would go on to make works as iconic as Donkey Kong, so why downplay their earliest attempts to work with material as iconic as this?

I'm sure Sheriff will came back 'round these parts, like a tumbleweed hops from Hollywood ghost towns to the raster screen. Don't lemme see ya causin' trouble in The Old MAME, son.

1994

The rose campion, a perennial pink-ish carnation found throughout temperate regions, has long been the study of biologists and botanists, from Darwin to Mendel. Now called silene coronaria, it formerly bore the designation lychnis, associated with a herbivorous moth of the same name, both fragile and humble. In this sense, this duo's unlikely contributions to modern life sciences mirror that of the original Korean PC platformer sharing the moniker, itself a key release for its field. I wish I could more easily recommend Softmax's first release beyond its historic significance, as the game itself is frustratingly unpolished and shows so much missed potential. But like its namesake, one shouldn't expect too much from what's just the beginnings of these ludo-scientists' forays into genres once untenable in this realm.

Video games in South Korea during the early '90s (well before today's glut of MMOs and mobile Skinner boxes) fell into two boxes: action-packed arcade releases and slower, more story-driven xRPGs and puzzlers on IBM-compatible PCs. The relative lack of consoles in the country—first because of low-quality bootlegs and second due to government bans on certain Japanese exports in the aftermath of WWII—meant that home enthusiasts needed a desktop computer to try anything outside the game centers. Anyone in the Anglosphere from that era can attest to so many CGA-/EGA-age struggles with rendering fast scrolling scenes and action, a feat relegated to works like Commander Keen or the occasional shoot-em-up such as Dragon Force: The Day 3. Even ambitious early iterations on JP-imported genres like the action-RPG suffered from choppy performance and limited colors, as was the case for Zinnia. VGA video and graphics accelerators, plus the rise of Windows 95 and GPUs, meant that PC compatibles could finally compete with TV hardware on arcade-like visuals and the aspirations that made possible. Lychnis was arguably the first non-STG Korean home title to herald this change.

Made by Artcraft, a grassroots team led by Hyak-kun Kim (later head of Gravity, creators of Ragnarok Online) and Yeon-kyu Choe (main director at publisher Softmax, leading tentpole series like War of Genesis), this was hardly an auspicious project. Yes, proving that VGA-equipped PCs just entering the market could handle something akin to Super Mario World was a challenge, but they didn't have much time or budget to make this a reality. And that shows throughout most of Lychnis' 15 levels, varying wildly in design quality, variety, and conveyance to players. I suspect that, like so many Korean PC games up through the turn of the millennium, this didn't get much playtesting beyond the developers themselves, who obviously knew how to play their own game quite well. Nor does this floppy-only game always play ball in DOSBox; whatever you do, keep the sound effects set to PC speaker, or this thing will just crash before you can even get past the vanity plate!

Still, the Falcom-esque opening sequence and fantasy artwork, vibrant and rich with that signature '90s D&D-inspired look, shows a lot of promise for new players. Same goes for the AdLib FM-synth soundtrack and crunchy PCM sound throughout your playthrough, with bubbly driving melodies fitting each world and a solid amount of aural feedback during tough action or platforming. There's a surprising amount of polish clashing against jank, which made my experience all the more beguiling. How could a team this evidently talented drop the ball in some very key areas? Was this the result of a rocky dev cycle, perhaps the main reason why Kim and Choe both splintered after this game and brought different friends to different companies? Just as the moth feeds upon the flower, this experiment in translating arcade and console play to monitor and keyboard was just one more casualty that would repeat itself, followed by other small studios making action/platformer/etc. debuts before working towards beefier software.

Lychnis drew in crowds of malnourished PC gamers with its heavy amount of smooth vertical and horizontal scrolling, harkening to the likes of Sonic and other mascots. (There's even a porcupine baddie early in the game which feels like an ode to SEGA's superstar.) Its premise also has a cute young adult appeal, with you choosing either the wall-jumping titular character in knight's armor, or his friend Iris, a cheeky mage with a very useful double jump and projectiles. Either way, we're off to defeat an evil sorcerer hell-bent on reviving ancient powers to conquer the continent of Laurasia. The worlds we visit reflect that treacherous journey away from home, starting in verdant fields, hills, and skies before ending within Sakiski's dread citadel full of traps and monsters. Anyone who's played a classic Ys story should recognize the similarities, and parts of this adventure brought Adol's trials in Esteria or Felghana to mind.

However, this still most resembles a platformer more like Wardner, Rastan, or the aforementioned Mario titles on Super Nintendo. The game loop consists of reaching each level's crystalline endpoint and then visiting the shop if you've acquired the requisite keycard. Pro tip: raise max continues to 5 and lives to 7. Lychnis doesn't ramp up its difficult right from the get-go, but World 1-3 presents the first big challenge, an arduous auto-scrolling climb from trees to clouds with no checkpoints whatsoever. I couldn't help but feel the designers struggled to decide if this would focus on 1CC play or heavy continues usage. There's a couple levels, both auto-scrollers, placed around mid-game which are very clearly meant to force Game Overs upon unsuspecting players who aren't concentrating and memorizing. Your lack of control per jump makes Iris the easy pick just for having more opportunities to correct trajectory, both for gaps and to keep distance from enemies and their attacks. Progressing through stages rarely feels that confusing in a navigation sense, but most present puzzles of varying efficacy which can impede you and lead to retries. With no saves or passwords, nor ways to gain continues or lives through high scores, this journey's very unforgiving for most today.

Thankfully there's only one case of multiple dubiously engineered levels in a row, unfortunately coming a bit early with 2-2 and 2-3. The former's just outright broken unless you play a certain way, having to time your attacks and positioning upon each set of mine-carts as tons of obstacles threaten to knock you off. Someone in the office must have had a penchant for auto-scrollers, which live up to their foul reputation whenever they appear here. (I'll cut 3-3 some slack for having a more unique combat-heavy approach, plus being a lot shorter, but it's still a waste of space vs. a fully fleshed-out exploratory jaunt across the seas.) 2-3, meanwhile, shows how masochistic Lychnis can get, with many blind jumps, sudden bursts of enemies from off-screen knocking you down bottomless pits, and lava eruptions casting extra hazards down upon you for insult to injury. Contrast this with the demanding but far fairer platforming gauntlets in 2-1, 3-2, and all of World 4's surprisingly non-slippery icy reaches. "All over the place" describes the content on offer here, and I could hardly accuse Artcraft of, um, crafting a boring or indistinct trip across these biomes.

What Lychnis does excel at is its pacing and means of livening up potential filler via an upgrades system. Thoroughly exploring stages, and clearing as many enemies and chests as you can find, builds up your coffers over time. Survive long enough, farm those 1-Ups and gold sacks, and eventually those top-tier weapons and armor are affordable, plus the ever nifty elixir that refills your life once between shops. This learn-die-hoard-buy loop takes most of the sting away from otherwise mirthless runs through these worlds, but is unfortunately tied to the game's most egregious failing: its one and only boss fight. Ever wonder how the rock-paper-scissors encounters from classic Alex Kidd games could get worse?! This game manages it by basically having you play slots with the big bad, where one either matches all symbols for damage or fails and takes a beating themselves. Only having the best gear makes this climactic moment reliably winnable, which I think is a step too far towards punishing all players, even the most skilled. It sucks because I kind of enjoy 5-3 right before, a very dungeon crawler-esque finale with lots of mooks to juggle and careful resource management. The ending sequence itself is as nice and triumphant as I'd expect, but what came right before was a killjoy.

I've shown a lot of mixed feelings for this so far, yet I still would recommend Lychnis to any classic 2D bump-and-jump aficionados who can appreciate the history behind this Frankenstein. For all my misgivings, it still felt to satisfying to learn the ins and outs, optimize my times, and somewhat put to rest that sorcerer's curse of not having played many Korean PC games. Of course, both Softmax and its offshoot Gravity would soon well surpass this impressive but unready foundation, whose success led to the frenetic sci-fi blockbuster Antman 2 and idiosyncratic pre-StarCraft strategy faire like Panthalassa. I suspect this thorny rose among Korean classics won't rank with many others waiting in my backlog, not that it's done a disservice by those later games fulfilling Artcraft's vision and promises of DOS-/Windows-era software finally reaching the mainstream. The biggest shame is how fragile that region's games industry has always been, from early dalliances with bootlegs and largely text-driven titles to the market constricting massively towards MMOs and other stuff built only for Internet cafes (no shade to those, though).

Just about the biggest advantage these classic Korean floppy and CD releases have over, say, anything for PC-98 is their ease of emulation. Lychnis remains abandonware, the result of its publisher not caring to re-release or even remaster this for Steam and other distributors. Free downloads are just a hop and a skip away, though none of these games have anything like the GOG treatment. With recent news of Project EGG bringing classic Japanese PC games to Switch, though, perhaps there's a chance that other East Asian gems and curiosities can find a place in the sun once more. Well, I can dream.

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Mar. 14 - 20, 2023 LATE

Video games in South Korea during the early '90s (well before today's glut of MMOs and mobile Skinner boxes) fell into two boxes: action-packed arcade releases and slower, more story-driven xRPGs and puzzlers on IBM-compatible PCs. The relative lack of consoles in the country—first because of low-quality bootlegs and second due to government bans on certain Japanese exports in the aftermath of WWII—meant that home enthusiasts needed a desktop computer to try anything outside the game centers. Anyone in the Anglosphere from that era can attest to so many CGA-/EGA-age struggles with rendering fast scrolling scenes and action, a feat relegated to works like Commander Keen or the occasional shoot-em-up such as Dragon Force: The Day 3. Even ambitious early iterations on JP-imported genres like the action-RPG suffered from choppy performance and limited colors, as was the case for Zinnia. VGA video and graphics accelerators, plus the rise of Windows 95 and GPUs, meant that PC compatibles could finally compete with TV hardware on arcade-like visuals and the aspirations that made possible. Lychnis was arguably the first non-STG Korean home title to herald this change.

Made by Artcraft, a grassroots team led by Hyak-kun Kim (later head of Gravity, creators of Ragnarok Online) and Yeon-kyu Choe (main director at publisher Softmax, leading tentpole series like War of Genesis), this was hardly an auspicious project. Yes, proving that VGA-equipped PCs just entering the market could handle something akin to Super Mario World was a challenge, but they didn't have much time or budget to make this a reality. And that shows throughout most of Lychnis' 15 levels, varying wildly in design quality, variety, and conveyance to players. I suspect that, like so many Korean PC games up through the turn of the millennium, this didn't get much playtesting beyond the developers themselves, who obviously knew how to play their own game quite well. Nor does this floppy-only game always play ball in DOSBox; whatever you do, keep the sound effects set to PC speaker, or this thing will just crash before you can even get past the vanity plate!

Still, the Falcom-esque opening sequence and fantasy artwork, vibrant and rich with that signature '90s D&D-inspired look, shows a lot of promise for new players. Same goes for the AdLib FM-synth soundtrack and crunchy PCM sound throughout your playthrough, with bubbly driving melodies fitting each world and a solid amount of aural feedback during tough action or platforming. There's a surprising amount of polish clashing against jank, which made my experience all the more beguiling. How could a team this evidently talented drop the ball in some very key areas? Was this the result of a rocky dev cycle, perhaps the main reason why Kim and Choe both splintered after this game and brought different friends to different companies? Just as the moth feeds upon the flower, this experiment in translating arcade and console play to monitor and keyboard was just one more casualty that would repeat itself, followed by other small studios making action/platformer/etc. debuts before working towards beefier software.

Lychnis drew in crowds of malnourished PC gamers with its heavy amount of smooth vertical and horizontal scrolling, harkening to the likes of Sonic and other mascots. (There's even a porcupine baddie early in the game which feels like an ode to SEGA's superstar.) Its premise also has a cute young adult appeal, with you choosing either the wall-jumping titular character in knight's armor, or his friend Iris, a cheeky mage with a very useful double jump and projectiles. Either way, we're off to defeat an evil sorcerer hell-bent on reviving ancient powers to conquer the continent of Laurasia. The worlds we visit reflect that treacherous journey away from home, starting in verdant fields, hills, and skies before ending within Sakiski's dread citadel full of traps and monsters. Anyone who's played a classic Ys story should recognize the similarities, and parts of this adventure brought Adol's trials in Esteria or Felghana to mind.

However, this still most resembles a platformer more like Wardner, Rastan, or the aforementioned Mario titles on Super Nintendo. The game loop consists of reaching each level's crystalline endpoint and then visiting the shop if you've acquired the requisite keycard. Pro tip: raise max continues to 5 and lives to 7. Lychnis doesn't ramp up its difficult right from the get-go, but World 1-3 presents the first big challenge, an arduous auto-scrolling climb from trees to clouds with no checkpoints whatsoever. I couldn't help but feel the designers struggled to decide if this would focus on 1CC play or heavy continues usage. There's a couple levels, both auto-scrollers, placed around mid-game which are very clearly meant to force Game Overs upon unsuspecting players who aren't concentrating and memorizing. Your lack of control per jump makes Iris the easy pick just for having more opportunities to correct trajectory, both for gaps and to keep distance from enemies and their attacks. Progressing through stages rarely feels that confusing in a navigation sense, but most present puzzles of varying efficacy which can impede you and lead to retries. With no saves or passwords, nor ways to gain continues or lives through high scores, this journey's very unforgiving for most today.

Thankfully there's only one case of multiple dubiously engineered levels in a row, unfortunately coming a bit early with 2-2 and 2-3. The former's just outright broken unless you play a certain way, having to time your attacks and positioning upon each set of mine-carts as tons of obstacles threaten to knock you off. Someone in the office must have had a penchant for auto-scrollers, which live up to their foul reputation whenever they appear here. (I'll cut 3-3 some slack for having a more unique combat-heavy approach, plus being a lot shorter, but it's still a waste of space vs. a fully fleshed-out exploratory jaunt across the seas.) 2-3, meanwhile, shows how masochistic Lychnis can get, with many blind jumps, sudden bursts of enemies from off-screen knocking you down bottomless pits, and lava eruptions casting extra hazards down upon you for insult to injury. Contrast this with the demanding but far fairer platforming gauntlets in 2-1, 3-2, and all of World 4's surprisingly non-slippery icy reaches. "All over the place" describes the content on offer here, and I could hardly accuse Artcraft of, um, crafting a boring or indistinct trip across these biomes.

What Lychnis does excel at is its pacing and means of livening up potential filler via an upgrades system. Thoroughly exploring stages, and clearing as many enemies and chests as you can find, builds up your coffers over time. Survive long enough, farm those 1-Ups and gold sacks, and eventually those top-tier weapons and armor are affordable, plus the ever nifty elixir that refills your life once between shops. This learn-die-hoard-buy loop takes most of the sting away from otherwise mirthless runs through these worlds, but is unfortunately tied to the game's most egregious failing: its one and only boss fight. Ever wonder how the rock-paper-scissors encounters from classic Alex Kidd games could get worse?! This game manages it by basically having you play slots with the big bad, where one either matches all symbols for damage or fails and takes a beating themselves. Only having the best gear makes this climactic moment reliably winnable, which I think is a step too far towards punishing all players, even the most skilled. It sucks because I kind of enjoy 5-3 right before, a very dungeon crawler-esque finale with lots of mooks to juggle and careful resource management. The ending sequence itself is as nice and triumphant as I'd expect, but what came right before was a killjoy.

I've shown a lot of mixed feelings for this so far, yet I still would recommend Lychnis to any classic 2D bump-and-jump aficionados who can appreciate the history behind this Frankenstein. For all my misgivings, it still felt to satisfying to learn the ins and outs, optimize my times, and somewhat put to rest that sorcerer's curse of not having played many Korean PC games. Of course, both Softmax and its offshoot Gravity would soon well surpass this impressive but unready foundation, whose success led to the frenetic sci-fi blockbuster Antman 2 and idiosyncratic pre-StarCraft strategy faire like Panthalassa. I suspect this thorny rose among Korean classics won't rank with many others waiting in my backlog, not that it's done a disservice by those later games fulfilling Artcraft's vision and promises of DOS-/Windows-era software finally reaching the mainstream. The biggest shame is how fragile that region's games industry has always been, from early dalliances with bootlegs and largely text-driven titles to the market constricting massively towards MMOs and other stuff built only for Internet cafes (no shade to those, though).

Just about the biggest advantage these classic Korean floppy and CD releases have over, say, anything for PC-98 is their ease of emulation. Lychnis remains abandonware, the result of its publisher not caring to re-release or even remaster this for Steam and other distributors. Free downloads are just a hop and a skip away, though none of these games have anything like the GOG treatment. With recent news of Project EGG bringing classic Japanese PC games to Switch, though, perhaps there's a chance that other East Asian gems and curiosities can find a place in the sun once more. Well, I can dream.

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Mar. 14 - 20, 2023 LATE

2014

funny how the one MOBA I've ever played only caught my eye because the devs conceived it as a modernized Herzog Zwei, except that's something they kinda got away from over time...

I played this back during its alpha phase, before Ubisoft brought it to consoles. Nothing tells me what pushed these guys into trying silly things like a VR port when they could have changed up the core modes, or anything to make this stand out from the crowd. Granted, someone more active in the beta and release periods would know more about whether or not this ended up and remained fun to play. This was also the only time I ever played a Chrome Store game, something the IGDB/Backloggd page won't tell you about its origins. That period of web-based free-to-play games seems to have waned, or just folded into the background as everyone and their mother does that stuff via Roblox instead. Funny how these trends come and go, only as prescient or permanent as the market and its manipulators demand.

Basically, imagine the aforementioned Tecno Soft RTS for Mega Drive, just with distinct factions and heroes + the usual mess of loadout management and heavy micro associated with this genre. Something tells me that I gravitated towards AirMech to fill the Battle.net gap in my soul, not having a Windows PC good enough for StarCraft II and having no idea (at the time) how to get classic Blizzard online games going. The ease of matching with relatively equally skilled players early on helped here, as I generally won and lost games in that desirable tug-of-war pattern you'd hope for. Quickly managing unit groups, keeping up pressure in lanes and the neat lil' alleys on each map, all while doing plenty of your own shooting and distraction using the hero unit-meets-cursor...this had a lot going for it.

There's a bit of a trend with very beloved and played free-to-play classics getting, erm, "classic" fan remasters years down the line, e.g. RuneScape or Team Fortress 2. But because AirMech was always closed source and never had that level of traction (some would argue distinction in this crowded genre), there's no way for me to revisit the pre-buyout era and place my memories on trial. What I've seen from AirMech Arena, meanwhile, seems more soulless and bereft of unique or meaningful mechanics and community. It's very easy to just play Herzog Zwei online via emulators or the SEGA Ages release on Switch, too, and that's held up both in legacy and playability. So the niche this web-MOBA/-RTS experiment tried to address is now flush with alternatives, let alone the origins they all point to.

Maybe this just sounds like excuses for me not to download the damn thing and give it a whirl. All I know is this led me to playing Caveman 2 Cosmos and saving up more for my 3DS library at the time. The beta didn't exactly develop that fast, and when it did, the general concept and game loop started favoring ride-or-die players over those like me who just wanted to occasionally hop in and have a blast. Balancing for both invested regulars and casual fans is a bitch and a half, yet I also can't imagine this would have been fun if imbalanced towards skilled folks constantly redefining the meta. The extensive mod-ability and "anything goes" attitude of classic Battle.net games definitely wasn't and isn't a thing for AirMech, nor do I suspect the developers ever wanted that. If it's a focused, overly polished RTS-MOBA you're looking for, I'm sure there's worse out there, but this no longer has that scrappy, Herzog-like simplicity that I crave.

The premise still has a lot of potential, even if Carbon Games seems content with where they've brought the series so far. I'd love to have a more story-focused, singleplayer-friendly variation, something which spiritual predecessors like NetStorm surely could have used. Until then, eh. This one's just here, sitting in the back of my community college neurons, taunting me with what could have been.

I played this back during its alpha phase, before Ubisoft brought it to consoles. Nothing tells me what pushed these guys into trying silly things like a VR port when they could have changed up the core modes, or anything to make this stand out from the crowd. Granted, someone more active in the beta and release periods would know more about whether or not this ended up and remained fun to play. This was also the only time I ever played a Chrome Store game, something the IGDB/Backloggd page won't tell you about its origins. That period of web-based free-to-play games seems to have waned, or just folded into the background as everyone and their mother does that stuff via Roblox instead. Funny how these trends come and go, only as prescient or permanent as the market and its manipulators demand.

Basically, imagine the aforementioned Tecno Soft RTS for Mega Drive, just with distinct factions and heroes + the usual mess of loadout management and heavy micro associated with this genre. Something tells me that I gravitated towards AirMech to fill the Battle.net gap in my soul, not having a Windows PC good enough for StarCraft II and having no idea (at the time) how to get classic Blizzard online games going. The ease of matching with relatively equally skilled players early on helped here, as I generally won and lost games in that desirable tug-of-war pattern you'd hope for. Quickly managing unit groups, keeping up pressure in lanes and the neat lil' alleys on each map, all while doing plenty of your own shooting and distraction using the hero unit-meets-cursor...this had a lot going for it.

There's a bit of a trend with very beloved and played free-to-play classics getting, erm, "classic" fan remasters years down the line, e.g. RuneScape or Team Fortress 2. But because AirMech was always closed source and never had that level of traction (some would argue distinction in this crowded genre), there's no way for me to revisit the pre-buyout era and place my memories on trial. What I've seen from AirMech Arena, meanwhile, seems more soulless and bereft of unique or meaningful mechanics and community. It's very easy to just play Herzog Zwei online via emulators or the SEGA Ages release on Switch, too, and that's held up both in legacy and playability. So the niche this web-MOBA/-RTS experiment tried to address is now flush with alternatives, let alone the origins they all point to.

Maybe this just sounds like excuses for me not to download the damn thing and give it a whirl. All I know is this led me to playing Caveman 2 Cosmos and saving up more for my 3DS library at the time. The beta didn't exactly develop that fast, and when it did, the general concept and game loop started favoring ride-or-die players over those like me who just wanted to occasionally hop in and have a blast. Balancing for both invested regulars and casual fans is a bitch and a half, yet I also can't imagine this would have been fun if imbalanced towards skilled folks constantly redefining the meta. The extensive mod-ability and "anything goes" attitude of classic Battle.net games definitely wasn't and isn't a thing for AirMech, nor do I suspect the developers ever wanted that. If it's a focused, overly polished RTS-MOBA you're looking for, I'm sure there's worse out there, but this no longer has that scrappy, Herzog-like simplicity that I crave.

The premise still has a lot of potential, even if Carbon Games seems content with where they've brought the series so far. I'd love to have a more story-focused, singleplayer-friendly variation, something which spiritual predecessors like NetStorm surely could have used. Until then, eh. This one's just here, sitting in the back of my community college neurons, taunting me with what could have been.

1980

tim rogers voice I Was a Sierra On-Line Poser smashes keyboard on stage and plays foosball with the keycaps

Like many others who love media history but struggle to get into or make time for certain parts of it, the formative parser-driven adventure games like Wander, Colossal Cave Adventure, and Sierra On-Line's classics like Mystery House have eluded me. But I'm also guilty of just not going for them like a hunter chases flock, or a prospector dives for gold. To have this apathy, despite knowing pretty much all these games are easily playable on Internet Archive, ate at me until recently. Something's clicked—probably just the satisfaction of completing Myst last month after years of never clearing the first island. But that's enough to get me committed to trying these ramshackle first attempts at conjuring immersive worlds on the earliest home computer platforms.

Mission Asteroid had a simple, er, mission: introduce any and all possible Apple II users to the graphic text adventure. Roberta Williams knew this didn't have to be as intricate as her Agatha Christie-esque first game, nor as fanciful as The Wizard and the Princess. A solid, pulp-y "save the Earth!" story could get you used to the studio's text parser, thinking up valid verb combinations, and managing your time and patience wisely. No matter how much this game continues to age like an indescribable beverage, it still fulfills those criteria. That's a nice way of saying this 1980 release had much less bullshit puzzling and navigation than its peers.

What the Williams duo would have called "simple" or "entry-level" then is considered hard to parse today dodges tomatoes after that pun. You've got the usual N-S-E-W compass commands, sure, but also instances of having to enter door rather than just go north through it. The two-word restriction on your interactions becomes painfully clear when trying to do something as straightforward as insert a floppy disk into the mission HQ Apple II. You type take disk, carriage return, and then insert disk (repeat), only for the game to ask where you're inserting this thing. There's no death branch here if you specify the wrong target or anything, just needless busywork compounded by the parser system.

Yet, for all the grief these simplistic parsers give me, there's still the fun of tinkering with what hidden-in-plain-sight options you can type in. All the gizmos in your space rocket can either doom you or take you on a disorienting ride through Earth orbit, controlled only by your type-in commands. Wandering the asteroid itself becomes a tense adventure as you likely know from harsh experience that the air supply's time-limited. Once the game lifts its tutorializing gaze from you, Mission Asteroid feels like an organic interplay between you, the reader asking questions, and the ghost of a game master hiding in the machine. It's easier now to see how Roberta, Ken, and others who'd soon join On-Line Systems could champion this genre framework.

Obviously there's not much to look at in this now, with its rudimentary VersaWriter drawings and lack of sound design. At the end of the day, most of the puzzles are either too simple to satisfy or convoluted enough to irritate me a bit too much. But I can gladly say that Mission Asteroid's an easier way to start playing turn-of-the-'80s graphic text stories than I've been told. It gets you into the necessary frame of mind with relatively little condescending scenarios or design language. The truly brutal riddles and cat's cradles of contemporary text adventures are reduced in scope, tightening up the pace. One gets to have a just-filling-enough time with the genre here before it overstays its welcome, either by avoiding a glut of bad ends or treating the player's time with more respect. I sense and can only speculate that Roberta's need to finish this romp for the holidays, capitalizing on Mystery House's success, left less room for potentially harmful experiments or indulgence.

So it's the definition of mid, yet I can't hold that against this game in retrospect. There's much worse one could try from that era, ranging from Scott Adams' pioneering all-text enigmas to their slapdash imitators on TRS-80 or Commodore PET (take your pick of PC cheaper than the Apple ][+). Given how Mission Asteroid itself avoids some of the amateur mistakes in Mystery House I hear about, I'm not content slapping this with a 2-star and calling it there. Whether or not it's a labor of love on par with Sierra On-Line's adventures soon to come, this little ditty of a day's work blowing up an asteroid punches above its weight class where it counts. Some higher being oughta know we got more than we asked for when Michael Bay's people adapted the premise almost two decades later. Keep it simple, Sierra!

Like many others who love media history but struggle to get into or make time for certain parts of it, the formative parser-driven adventure games like Wander, Colossal Cave Adventure, and Sierra On-Line's classics like Mystery House have eluded me. But I'm also guilty of just not going for them like a hunter chases flock, or a prospector dives for gold. To have this apathy, despite knowing pretty much all these games are easily playable on Internet Archive, ate at me until recently. Something's clicked—probably just the satisfaction of completing Myst last month after years of never clearing the first island. But that's enough to get me committed to trying these ramshackle first attempts at conjuring immersive worlds on the earliest home computer platforms.

Mission Asteroid had a simple, er, mission: introduce any and all possible Apple II users to the graphic text adventure. Roberta Williams knew this didn't have to be as intricate as her Agatha Christie-esque first game, nor as fanciful as The Wizard and the Princess. A solid, pulp-y "save the Earth!" story could get you used to the studio's text parser, thinking up valid verb combinations, and managing your time and patience wisely. No matter how much this game continues to age like an indescribable beverage, it still fulfills those criteria. That's a nice way of saying this 1980 release had much less bullshit puzzling and navigation than its peers.

What the Williams duo would have called "simple" or "entry-level" then is considered hard to parse today dodges tomatoes after that pun. You've got the usual N-S-E-W compass commands, sure, but also instances of having to enter door rather than just go north through it. The two-word restriction on your interactions becomes painfully clear when trying to do something as straightforward as insert a floppy disk into the mission HQ Apple II. You type take disk, carriage return, and then insert disk (repeat), only for the game to ask where you're inserting this thing. There's no death branch here if you specify the wrong target or anything, just needless busywork compounded by the parser system.

Yet, for all the grief these simplistic parsers give me, there's still the fun of tinkering with what hidden-in-plain-sight options you can type in. All the gizmos in your space rocket can either doom you or take you on a disorienting ride through Earth orbit, controlled only by your type-in commands. Wandering the asteroid itself becomes a tense adventure as you likely know from harsh experience that the air supply's time-limited. Once the game lifts its tutorializing gaze from you, Mission Asteroid feels like an organic interplay between you, the reader asking questions, and the ghost of a game master hiding in the machine. It's easier now to see how Roberta, Ken, and others who'd soon join On-Line Systems could champion this genre framework.

Obviously there's not much to look at in this now, with its rudimentary VersaWriter drawings and lack of sound design. At the end of the day, most of the puzzles are either too simple to satisfy or convoluted enough to irritate me a bit too much. But I can gladly say that Mission Asteroid's an easier way to start playing turn-of-the-'80s graphic text stories than I've been told. It gets you into the necessary frame of mind with relatively little condescending scenarios or design language. The truly brutal riddles and cat's cradles of contemporary text adventures are reduced in scope, tightening up the pace. One gets to have a just-filling-enough time with the genre here before it overstays its welcome, either by avoiding a glut of bad ends or treating the player's time with more respect. I sense and can only speculate that Roberta's need to finish this romp for the holidays, capitalizing on Mystery House's success, left less room for potentially harmful experiments or indulgence.

So it's the definition of mid, yet I can't hold that against this game in retrospect. There's much worse one could try from that era, ranging from Scott Adams' pioneering all-text enigmas to their slapdash imitators on TRS-80 or Commodore PET (take your pick of PC cheaper than the Apple ][+). Given how Mission Asteroid itself avoids some of the amateur mistakes in Mystery House I hear about, I'm not content slapping this with a 2-star and calling it there. Whether or not it's a labor of love on par with Sierra On-Line's adventures soon to come, this little ditty of a day's work blowing up an asteroid punches above its weight class where it counts. Some higher being oughta know we got more than we asked for when Michael Bay's people adapted the premise almost two decades later. Keep it simple, Sierra!

1982

Making cartridge games in the pre-Famicom years posed a dilemma: they couldn't store much game without costing customers and manufacturers out the butt. It's no surprise that Nintendo later made their own disk add-on, among others, in order to distribute cheaper, larger software. All the excess cart inventory that flooded North American console markets, thus precipitating the region's early-'80s crash, finally got discounted to rates we'd expect today. And it's in that period of decline where something like Miner 2049er would have appealed to Atari PC owners normally priced out of cart games.

This 16K double-board release promised 10 levels of arcade-y, highly replayable platform adventuring, among other items of praise littering the pages of newsletters and magazines. Just one problem: it's a poor mash-up of Donkey Kong, Pac-Man, and other better cabinet faire you'd lose less quarters from and enjoy more. This was the same year one could find awesome, innovative experiences like Moon Patrol down at the bar or civic center, let alone Activision's Pitfall and other tech-pushing Atari VCS works. Hell, I'd rather deal with all the exhausting RNG-laden dungeons of Castle Wolfenstein right now than bother with a jack of all trades + master of none such as this.

I don't mean to bag on Bill Hogue's 1982 work that much, knowing the trials and tribulations of bedroom coding in those days. He'd made a modest living off many TRS-80 clones of arcade staples, only having to make this once Radio Shack/Tandy discontinued that platform. His studio Big Five debuted on Apple II & Atari 800 with this unwieldy thing, so large they couldn't smush it into the standard cartridge size of the latter machine. Contrast this with David Crane's masterful compression of Pitfall into just 4 kiloybytes, a quarter as big yet much more enjoyable a play. Surely all these unique stages in Miner 2049er would have given it the edge on other primordial platformers, right? That's what I hoped for going in, not that I expected anything amazing. To my disappointment, its mechanics, progression, and overall game-feel just seems diluted to the point of disrespecting its inspirations.

The premise doesn't make a great impression: rather than reaching an apex or collecting an item quota to clear the stage, you must walk across each and every colorable tile to proceed. Anyone who's played Crush Roller or that stamp minigame in Mario Party 4 (among other odd examples) should recognize this. The only bits of land you need not worry about are elevator/teleporter floors and ladders, but the game requires you to complete a tour of everything else. In addition to padding out my playthrough without much sense of accomplishment, this also let me spend more time with Miner 2049er's platforming physics. And the verdict is they're not good. Falling for even a couple seconds kills you, and a lack of air control means mistimed jumps are fatal. The way jumps carry more horizontal inertia than vertical always throws me off a bit, too. Folks love to complain about a lack of agility or failure avoidance in something like Spelunker, but that game and Donkey Kong at least feel more intuitive and consistent than this.

It wouldn't be so bad if the level designs weren't also full of one-hit-kill monsters and platforms with only the slightest elevation differences. The maze game influences come in strong with this game's enemies, which you can remove from the equation by grabbing bonus items, usually shovels or pickaxes and the like. Managing the critters' patterns, your available route(s), and proximity to these power-ups becomes more important the further in you get. But I rarely if ever felt satisfied by this game loop; the flatter, more fluid and tactical plane of action in Pac-Man et al. works way better. Combine all this with getting undone by the least expected missed jump, or running out of invincibility time right before touching a mook, and there's just more frustration than gratification.

Now it's far from an awful time, as the game hands you multiple lives and extends in case anything bad happens. The game occasionally exudes this charming, irreverent attitude towards Nintendo's precursor and the absurdity of this miner's predicament. Mediocrity wasn't as much of a sin back then, especially not when developers are trying to imitate and expand on new ideas. But I think Miner 2049er is a telltale case of how back-of-the-box features can't compensate for lack of polish or substance. For example, it took less than a year for Doug Smith's Lode Runner to do everything here way better, combining Donkey Kong & Heiankyo Alien with other osmotic influences to make a timeless puzzle platformer. The arcade adventure-platformer took on a distinct identity with Matthew Smith's Manic Miner, part of the European/UK PC game pantheon and itself born from the Trash 80's legacy. One could charitably claims that this pre-crash title never aspired to those competitors' ambitions, that it finds refuge in elegance or something. I wish I could agree, especially given its popularity and number of ports over the decade. All I know is this one ain't got a level editor, or subtle anti-Tory/-Thatcher political commentary. The only identity I can, erm, identify is that silly box art of the shaggy prospector and bovine buddy.

Give this a shot if you appreciate the history and context behind it, or just want something distinctly proto-shareware. I just can't muster much enthusiasm for a game this subpar and oddly mundane, both now and then. None of the conversions and remakes seem all that special either, though props to Epoch for bringing it to the Super Cassette Vision in '85. By the time this could have made a grand comeback on handhelds, Boulder Dash and other spelunking sorties basically obsoleted it. Minor 2049er indeed.

This 16K double-board release promised 10 levels of arcade-y, highly replayable platform adventuring, among other items of praise littering the pages of newsletters and magazines. Just one problem: it's a poor mash-up of Donkey Kong, Pac-Man, and other better cabinet faire you'd lose less quarters from and enjoy more. This was the same year one could find awesome, innovative experiences like Moon Patrol down at the bar or civic center, let alone Activision's Pitfall and other tech-pushing Atari VCS works. Hell, I'd rather deal with all the exhausting RNG-laden dungeons of Castle Wolfenstein right now than bother with a jack of all trades + master of none such as this.

I don't mean to bag on Bill Hogue's 1982 work that much, knowing the trials and tribulations of bedroom coding in those days. He'd made a modest living off many TRS-80 clones of arcade staples, only having to make this once Radio Shack/Tandy discontinued that platform. His studio Big Five debuted on Apple II & Atari 800 with this unwieldy thing, so large they couldn't smush it into the standard cartridge size of the latter machine. Contrast this with David Crane's masterful compression of Pitfall into just 4 kiloybytes, a quarter as big yet much more enjoyable a play. Surely all these unique stages in Miner 2049er would have given it the edge on other primordial platformers, right? That's what I hoped for going in, not that I expected anything amazing. To my disappointment, its mechanics, progression, and overall game-feel just seems diluted to the point of disrespecting its inspirations.

The premise doesn't make a great impression: rather than reaching an apex or collecting an item quota to clear the stage, you must walk across each and every colorable tile to proceed. Anyone who's played Crush Roller or that stamp minigame in Mario Party 4 (among other odd examples) should recognize this. The only bits of land you need not worry about are elevator/teleporter floors and ladders, but the game requires you to complete a tour of everything else. In addition to padding out my playthrough without much sense of accomplishment, this also let me spend more time with Miner 2049er's platforming physics. And the verdict is they're not good. Falling for even a couple seconds kills you, and a lack of air control means mistimed jumps are fatal. The way jumps carry more horizontal inertia than vertical always throws me off a bit, too. Folks love to complain about a lack of agility or failure avoidance in something like Spelunker, but that game and Donkey Kong at least feel more intuitive and consistent than this.

It wouldn't be so bad if the level designs weren't also full of one-hit-kill monsters and platforms with only the slightest elevation differences. The maze game influences come in strong with this game's enemies, which you can remove from the equation by grabbing bonus items, usually shovels or pickaxes and the like. Managing the critters' patterns, your available route(s), and proximity to these power-ups becomes more important the further in you get. But I rarely if ever felt satisfied by this game loop; the flatter, more fluid and tactical plane of action in Pac-Man et al. works way better. Combine all this with getting undone by the least expected missed jump, or running out of invincibility time right before touching a mook, and there's just more frustration than gratification.

Now it's far from an awful time, as the game hands you multiple lives and extends in case anything bad happens. The game occasionally exudes this charming, irreverent attitude towards Nintendo's precursor and the absurdity of this miner's predicament. Mediocrity wasn't as much of a sin back then, especially not when developers are trying to imitate and expand on new ideas. But I think Miner 2049er is a telltale case of how back-of-the-box features can't compensate for lack of polish or substance. For example, it took less than a year for Doug Smith's Lode Runner to do everything here way better, combining Donkey Kong & Heiankyo Alien with other osmotic influences to make a timeless puzzle platformer. The arcade adventure-platformer took on a distinct identity with Matthew Smith's Manic Miner, part of the European/UK PC game pantheon and itself born from the Trash 80's legacy. One could charitably claims that this pre-crash title never aspired to those competitors' ambitions, that it finds refuge in elegance or something. I wish I could agree, especially given its popularity and number of ports over the decade. All I know is this one ain't got a level editor, or subtle anti-Tory/-Thatcher political commentary. The only identity I can, erm, identify is that silly box art of the shaggy prospector and bovine buddy.

Give this a shot if you appreciate the history and context behind it, or just want something distinctly proto-shareware. I just can't muster much enthusiasm for a game this subpar and oddly mundane, both now and then. None of the conversions and remakes seem all that special either, though props to Epoch for bringing it to the Super Cassette Vision in '85. By the time this could have made a grand comeback on handhelds, Boulder Dash and other spelunking sorties basically obsoleted it. Minor 2049er indeed.

1983

Since the other reviews (so far) are only covering the very not good PC-88 & PC-98 ports, let's talk about the X1 original.

This isn't an amazing arcade shooter, at least not compared to Xevious or Star Force from the era. But it's a lot better than given credit, at least on Sharp X1 & MZ micros. I first got into playing this several years ago, each time warming up a bit more to how it plays. For comparison's sake, even the mighty Famicom wouldn't have any original STGs of this caliber & ambition until 1985 onward. Kotori Yoshimura built this turn-of-'84 tech showpiece all on her own, yet it's still fun if you like a more strategic open-range shooter. (I play this on an X1 emulator using cursor keys with no other enhancements or major changes.)

A big issue I see players having is keeping track of shots while landing your own, whether in air or on ground. Thankfully the game's soundscape, though sparse, makes enemy fire identifiable enough for quick dodging. Pay attention to the dull blips of enemy shots, and also keep a mental bead on where enemies are spawning. Certain foes will intercept you & lead shots better; they're usually a light pinkish-red in this version. I make sure to eliminate or avoid them as much as I can while bombing targets to find the real prize: the Dyradeizer bomb-ables.

It's possible to meticulously clear each stage, but the smart play for seeing more of the game (let alone clearing a loop) is to reach the stages' second phase quickly. Reaching the Dyradeizer side of each stage simplifies matters a lot since there's less dogfighting & more dodging turret fire. It's also simple to just destroy the Dyradeizer core ASAP if you're ready to proceed, rather than continuing to bomb out the rest. Getting through stages like this helps with learning movement & spawning behavior, which in turn makes playing for score much more manageable.

Enough strategy. What's the deal with Thunder Force on X1?! /seinfeld

I liken it to a long-lost pen pal of Raid on Bungeling Bay, but with more obvious Namco influences (ex. Xevious, Bosconian) and more impressive visuals. The X1 original uses the PC's built-in spriting hardware (the PCG chip) to handle stage objects & actors faster than any other PC STG of its time. This doesn't make it unplayable, but certainly zippier than you'd expect from a mid-era 8-bit micro. The simple control scheme, level progression, & enemy roster means it's easy to get started with Thunder Force. It's a very difficult game for sure, yet hardly a mystery. Maybe the enemy bullets could have been drawn more visibly, but they're readable enough after playing for 15 minutes.

The game's ports retain the solid game loop, particularly the scoring system & map/enemy variety, but massively lose out in other areas. (I'll exempt the MZ-1500 version here for being fairly close to X1 and arguably a better speed for some players who want to learn the game.) At that time, the PC-88 really couldn't handle this kind of game, even with the fastest pseudo-sprite coding in games like Kazuro Morita's Alphos. Surprisingly, even the more underpowered PC-6001 port feels better to play (and a lot more impressive) than that of its bigger cousin. And since the FM-7 release basically matches the PC-88 one, that makes for a poor but unsurprising showing. Yoshimura & her co-programmers had to make not just these ports in rapid succession, but tons of other quick ports during those pre-Mega Drive years at Tecno Soft. Rushed ports were common, and it's a travesty how many people get their first glance at this game via its less-than-representative versions.

One flaw that's always irked me is how the game handles shot collisions. You really have to commit to your own ground bombs, ex. not changing direction immediately while the shot lands, or else you risk not blowing something up. It's much less problematic with air fire thankfully, but hardly ideal. And there's the old problem of not being able to stop mid-flight, requiring you to manage your direction at all times. This leads to a lot of circular movement around parts of each stage if you're trying to destroy everything. Even I get a bit exhausted by this! But it's a matter of getting used to these weird physics & building your tactics around them. Pro tip: the game calculates enemy fire direction based on where you're flying when it's calculating their attacks. Use that to manipulate enemy fire away from you, then make your attack.

It's worth dealing with some odd collision detection & tricky enemy patterns for one of the best pick-up-and-play arcade originals defining the early J-PC software lineup. Yoshimura & her colleagues would proceed to form Arsys Soft a year or so later, where they made much better works like WiBARM & Star Cruiser. But games like Thunder Force showed her ability to evolve arcade-style play on a home platform—no mean feat at a time when Japanese PCs' hardware & developer support was more fragmented. Both as a history piece & a game today, Thunder Force on X1 is worth a shot if you like the rest of the series or want to experience how the early post-Galaga shooters began to evolve.

Also, I'm glad to say there's no quaint, irritating rendition of the William Tell Overture in this version. You can put on any music you'd like!

This isn't an amazing arcade shooter, at least not compared to Xevious or Star Force from the era. But it's a lot better than given credit, at least on Sharp X1 & MZ micros. I first got into playing this several years ago, each time warming up a bit more to how it plays. For comparison's sake, even the mighty Famicom wouldn't have any original STGs of this caliber & ambition until 1985 onward. Kotori Yoshimura built this turn-of-'84 tech showpiece all on her own, yet it's still fun if you like a more strategic open-range shooter. (I play this on an X1 emulator using cursor keys with no other enhancements or major changes.)

A big issue I see players having is keeping track of shots while landing your own, whether in air or on ground. Thankfully the game's soundscape, though sparse, makes enemy fire identifiable enough for quick dodging. Pay attention to the dull blips of enemy shots, and also keep a mental bead on where enemies are spawning. Certain foes will intercept you & lead shots better; they're usually a light pinkish-red in this version. I make sure to eliminate or avoid them as much as I can while bombing targets to find the real prize: the Dyradeizer bomb-ables.

It's possible to meticulously clear each stage, but the smart play for seeing more of the game (let alone clearing a loop) is to reach the stages' second phase quickly. Reaching the Dyradeizer side of each stage simplifies matters a lot since there's less dogfighting & more dodging turret fire. It's also simple to just destroy the Dyradeizer core ASAP if you're ready to proceed, rather than continuing to bomb out the rest. Getting through stages like this helps with learning movement & spawning behavior, which in turn makes playing for score much more manageable.

Enough strategy. What's the deal with Thunder Force on X1?! /seinfeld

I liken it to a long-lost pen pal of Raid on Bungeling Bay, but with more obvious Namco influences (ex. Xevious, Bosconian) and more impressive visuals. The X1 original uses the PC's built-in spriting hardware (the PCG chip) to handle stage objects & actors faster than any other PC STG of its time. This doesn't make it unplayable, but certainly zippier than you'd expect from a mid-era 8-bit micro. The simple control scheme, level progression, & enemy roster means it's easy to get started with Thunder Force. It's a very difficult game for sure, yet hardly a mystery. Maybe the enemy bullets could have been drawn more visibly, but they're readable enough after playing for 15 minutes.

The game's ports retain the solid game loop, particularly the scoring system & map/enemy variety, but massively lose out in other areas. (I'll exempt the MZ-1500 version here for being fairly close to X1 and arguably a better speed for some players who want to learn the game.) At that time, the PC-88 really couldn't handle this kind of game, even with the fastest pseudo-sprite coding in games like Kazuro Morita's Alphos. Surprisingly, even the more underpowered PC-6001 port feels better to play (and a lot more impressive) than that of its bigger cousin. And since the FM-7 release basically matches the PC-88 one, that makes for a poor but unsurprising showing. Yoshimura & her co-programmers had to make not just these ports in rapid succession, but tons of other quick ports during those pre-Mega Drive years at Tecno Soft. Rushed ports were common, and it's a travesty how many people get their first glance at this game via its less-than-representative versions.

One flaw that's always irked me is how the game handles shot collisions. You really have to commit to your own ground bombs, ex. not changing direction immediately while the shot lands, or else you risk not blowing something up. It's much less problematic with air fire thankfully, but hardly ideal. And there's the old problem of not being able to stop mid-flight, requiring you to manage your direction at all times. This leads to a lot of circular movement around parts of each stage if you're trying to destroy everything. Even I get a bit exhausted by this! But it's a matter of getting used to these weird physics & building your tactics around them. Pro tip: the game calculates enemy fire direction based on where you're flying when it's calculating their attacks. Use that to manipulate enemy fire away from you, then make your attack.

It's worth dealing with some odd collision detection & tricky enemy patterns for one of the best pick-up-and-play arcade originals defining the early J-PC software lineup. Yoshimura & her colleagues would proceed to form Arsys Soft a year or so later, where they made much better works like WiBARM & Star Cruiser. But games like Thunder Force showed her ability to evolve arcade-style play on a home platform—no mean feat at a time when Japanese PCs' hardware & developer support was more fragmented. Both as a history piece & a game today, Thunder Force on X1 is worth a shot if you like the rest of the series or want to experience how the early post-Galaga shooters began to evolve.

Also, I'm glad to say there's no quaint, irritating rendition of the William Tell Overture in this version. You can put on any music you'd like!

1979

The very first "realistic" arcade racing video games started off simplistic and barely evocative of what they promised players, but Speed Freak, the first example using vector graphics, does the night-racer concept best out of them all. It must have seemed like a huge leap forward upon release in 1979, three years after Atari engineer Dave Shepperd and his team used Reiner Forest's Nurburgring-1 as the basis for Night Driver (and then Midway's close competitor, 280 Zzzap). Representing the road with just scaling road markers zooming by, in and out of the vanishing point, was impressive enough in the late-'70s, yet Vectorbeam saw the potential for this concept if brought into wireframe 3D. Without changing the simple and immediate goal of driving as fast, far, and crash-less as possible, the company made what I'd tentatively call the best commercial driving sim of the decade, albeit without the fancy skeuomorphic cabinets of something like Fire Truck.

One coin nets players two minutes total of driving, dodging, shifting, and hopefully some high scorin'. Like its stylistic predecessors, the cabinet features a wheel and gated stick shift, giving you something tactile to steer and manage speed with other than the pedals. And that vector display! This expensive but awe-inspiring video tech debuted in arcade format back in '77 when Larry Rosenthal from MIT debuted a fast yet affordable Spacewar! recreation using these new screen drawing methods. Whereas Dr. Forest's early '76 German racing sim drew a basic road surface and lit up bulbs placed towards the glass to fake road edges, Atari and Midway used very early microprocessors and video ROM chips to render rasterized equivalents. Here, though, vivid scanlines of light emanated from the screen at a human-readable refresh rate, with far more on-road and off-road detail than before. Clever scaling of wiry objects on screen gives the impression of 3D perspective, and crashing leads to a broken windshield effect! All these features would have made this feel more comprehensive and immersive for arcade-goers than its peers, even compared to the most luxurious of electromechanical racing installations.