PasokonDeacon

Shelley Day, Ron Gilbert & co. making a cute 'lil kids adventure dominoes falling Humungous Entertainment co-founder convicted of defrauding bank to buy a dream home next door to Paul Allen

Oh, there's an actual game to talk about here, not just the sad irony of Humungous' downfall. It's just a rather simplistic experience aside from its then innovative take on the edutainment adventure. Most PC DOS & Mac software oriented towards this demographic at the time talked down to kids, rather than taking their wants and fears seriously. No more forced, obviously pedantic lessons you'd snooze through in the computer lab—Putt-Putt has an actual story to tell. And you're right in it with him, from proving your civic responsibility to homing a stray dog. It's a bit problematic in the sense that our purple funky four-wheeler mainly does this to, well, Join the Parade and all, but engaging and meaningful enough for almost any kindergartener. Just ignore how he could be saving lost puppies for its own sake. I got my start with Putt-Putt starting from the lunar sequel, but this felt oh so cozy and familiar in similar ways.

Gilbert's goals of empowering young players and avoiding condescension already show results here. The game opens with an effortless "tutorial" where Putt-Putt awakens at home and gets to toy around in the garage. It's here where you first encounter the studio's famous "click points", where seemingly mundane set dressing comes to life as you click around. Even the diegetic HUD, Putt-Putt's dashboard, has its own easter eggs, encouraging you to try interacting with anything on screen. From simple animations to complex multi-step interactions, these click points evolved from similar examples in earlier LucasArts and Cyan Worlds adventures, now used to intuitively advance the player's story by giving them a toybox of sorts.

That's really what saves this from a lower rating, as the plot is as basic and A-to-B as a Junior Adventure gets. Mowing lawns makes up the bulk of any challenge you'll find, and the puzzles couldn't be more elementary if they tried. Figuring out where to go and how to get the needed key items takes no time at all, for better or worse. This makes it a nice one-sitting game for its age group, no doubt. But the sequels add more interesting questing, click points, story sequences, etc. that Joins the Parade sorely lacks. It's the blueprint they'd all quickly surpass. I can't really poo-poo this adventure as such, nor can I rate it higher.

Can we at least talk about how uncanny Putt-Putt and his world looks in these first two MS-DOS entries? Pixel-era Humungous games had a lot of art jank, especially when characters look at the camera. Putt-Putt's proportions and facial expressions run the gamut from mildly off-model to humorously off-putting (pun intended). Some like to joke about him making a serial killer face here and in Goes to the Moon—I can totally see it. But that's also a charming reminder of the studio's beginnings, a bit before they moved to high-quality art and animation with Freddi Fish and their Windows 9x-era Junior Adventures.

What Myst did for the adult multimedia games market, Putt-Putt achieved for multimedia kids' games. This was an important step into the public eye for similar works like The Manhole, and a masterfully dialed-down, less lethal take on the point-and-click adventure during the genre's heyday. I just wish I could get more out of it nowadays, but that's what happens when you're used to the excellence of Pajama Sam or Spy Fox. Things only got more ambitious for the Junior Adventures in a short span of time, and it wasn't long before the parade left Putt-Putt's original story far behind.

Oh, there's an actual game to talk about here, not just the sad irony of Humungous' downfall. It's just a rather simplistic experience aside from its then innovative take on the edutainment adventure. Most PC DOS & Mac software oriented towards this demographic at the time talked down to kids, rather than taking their wants and fears seriously. No more forced, obviously pedantic lessons you'd snooze through in the computer lab—Putt-Putt has an actual story to tell. And you're right in it with him, from proving your civic responsibility to homing a stray dog. It's a bit problematic in the sense that our purple funky four-wheeler mainly does this to, well, Join the Parade and all, but engaging and meaningful enough for almost any kindergartener. Just ignore how he could be saving lost puppies for its own sake. I got my start with Putt-Putt starting from the lunar sequel, but this felt oh so cozy and familiar in similar ways.

Gilbert's goals of empowering young players and avoiding condescension already show results here. The game opens with an effortless "tutorial" where Putt-Putt awakens at home and gets to toy around in the garage. It's here where you first encounter the studio's famous "click points", where seemingly mundane set dressing comes to life as you click around. Even the diegetic HUD, Putt-Putt's dashboard, has its own easter eggs, encouraging you to try interacting with anything on screen. From simple animations to complex multi-step interactions, these click points evolved from similar examples in earlier LucasArts and Cyan Worlds adventures, now used to intuitively advance the player's story by giving them a toybox of sorts.

That's really what saves this from a lower rating, as the plot is as basic and A-to-B as a Junior Adventure gets. Mowing lawns makes up the bulk of any challenge you'll find, and the puzzles couldn't be more elementary if they tried. Figuring out where to go and how to get the needed key items takes no time at all, for better or worse. This makes it a nice one-sitting game for its age group, no doubt. But the sequels add more interesting questing, click points, story sequences, etc. that Joins the Parade sorely lacks. It's the blueprint they'd all quickly surpass. I can't really poo-poo this adventure as such, nor can I rate it higher.

Can we at least talk about how uncanny Putt-Putt and his world looks in these first two MS-DOS entries? Pixel-era Humungous games had a lot of art jank, especially when characters look at the camera. Putt-Putt's proportions and facial expressions run the gamut from mildly off-model to humorously off-putting (pun intended). Some like to joke about him making a serial killer face here and in Goes to the Moon—I can totally see it. But that's also a charming reminder of the studio's beginnings, a bit before they moved to high-quality art and animation with Freddi Fish and their Windows 9x-era Junior Adventures.

What Myst did for the adult multimedia games market, Putt-Putt achieved for multimedia kids' games. This was an important step into the public eye for similar works like The Manhole, and a masterfully dialed-down, less lethal take on the point-and-click adventure during the genre's heyday. I just wish I could get more out of it nowadays, but that's what happens when you're used to the excellence of Pajama Sam or Spy Fox. Things only got more ambitious for the Junior Adventures in a short span of time, and it wasn't long before the parade left Putt-Putt's original story far behind.

Love Is... conceiving your son Milo Casali by artificial insemination, to the chagrin of the Vatican, and announcing this proudly in your comic strip. Love Is... the Casali sons making their own staple of pop media in a similarly simple but unexpected way.

Love Is... the Plutonia Experiment, if I might be so bold. There's nothing but love throughout this entire mapset, a perennial standout among the classic Doom games for reasons debated to this day. For 1996, the mapping designs and concepts employed in PLUTONIA.WAD were avant-garde, yet seem very obvious and simple to modern Doom players. The Casali brothers were done playing by the rules and conventions fellow fan creators were bound to, from overt attempts at realism ("DoomCute" in today's parlage) to prizing adventuring and cheap thrills over exacting endurance tests of skill. For Dario & Milo, it was now or never to challenge, even brutalize their community. A kind of tough love, perhaps.

As a fanmade map pack turned second half of Final Doom, Plutonia serves as a necessary foil to TNT: Evilution's excesses and concessions. The Casalis bros. knew their community maps well, and had already been pushing the possibilities of the pre-source port Doom engine with solo releases like PUNISHER.WAD and BUTCHER.WAD. After id software witnessed their contributions to TNT.WAD—two of the most polished maps in that whole set, Dario's "Pharaoh" and Milo's "Heck"—they met and discussed making a whole new expansion pack to feature in Final Doom. The early maps they showed American McGee quickly became the start for Plutonia, which Dario & Milo had much less time to work on than TeamTNT had for their own mapset.

I could go further into The Plutonia Experiment's history, but Doomworld and Dario's own contributions paint more of the picture already. What you should know on a first playthrough is that one cannot just like this WAD. Nearly everyone I know in the Doom fandom either loves or hates this monument to mid-'90s FPS experimentation. It's more than reasonable to run through Plutonia on a lower difficulty since the maps are well-designed to retain their intensity and skill demands on Hurt Me Plenty at least. But the Casalis built this game as the kind of Japanese game show obstacle course any Doom player in '96 would approach with caution, if not trepidation. There's no remorse, little reprieve, and relatively few dull moments anywhere throughout Plutonia's alienating, jungle-laden mess of arenas, gauntlets, and set-pieces. Tough love indeed.

Not every level hits these marks. I can list some of my own pet-hate experiences, from the very poorly telegraphed "Indiana Jones" invisible bridge in MAP02: Well of Souls, to the cramped teleporting Archvile trap wrecking first-time players in MAP12: Speed. A couple of maps utterly put me off even now, mainly MAP20: The Death Domain (too many gotchas, not enough chances to take cover) or MAP30: Gateway to Hell (another needless tradition, the Icon of Sin finale). Otherwise, that leaves us with thirty difficult but rewarding maps combining Doom II's masterful combat design with more streamlined, less noodly levels to navigate. I think it's a winning combination, even if some 1996 contemporaries like the Memento Mori II mapset showcase prettier or more conceptually ambitious works.

One thing that absolutely works in Plutonia's favor is its difficult but fair approach to most combat scenarios. This is not anything like a Mario kaizo hack or masocore gaming in general. But you'll have every reason to approach fights strategically, using the right weapons and movement at the right time to survive. Both of the brothers prefer small but uniquely lethal combinations of monsters to the giant hordes you see in many popular maps today. Economy of design defines this set in contrast to not just Evilution, but other community-made packs from the time like Memento Mori. A single archvile, a couple revenants, and some cannon fodder imps...put them in a non-trivial space to travel around and you'll have one hell of a battle!

To this end, most maps shower you in higher-tier ammo for those upper-level weapons. Expect to learn the ins and outs of rocket launcher splash damage, or how to efficiently wield the BFG's invisible tracer spread fire. Practice hard enough and you'll get a feel for how to conserve super shotgun ammo as you mow down pinkies, or the basics of redirecting skeleton fireballs into other foes to get them infighting. The Casalis weren't making hard-ass shit for the sake of being hardasses. At a time when speedrunning demos were gaining popularity and the Doom community's skills and metagame were evolving, these two just wanted to gift everyone a bloody chocolate box for Valentine's. True love waits.

Funny thing is, these maps aren't as bizarre or off-putting as one might think, at least when you realize they're clever remixes of id's own levels! It makes sense how, with only several weeks to build and test their vanilla-compatible maps largely by themselves, the Casalis would chop up useful bits from Doom I & II for their own purposes. Milo's MAP21: Slayer is an obvious riff on 'O' of Destruction and other Romero levels, for instance, while Dario's works like MAP08: Realm liberally borrow ideas from Sandy Petersen's oft-maligned creations. This does mean the set can't be as revelatory or unique as it could have, despite some memorable new ideas like the iconic archvile maze in MAP11. Still, there's plenty of clever trope reuse all throughout Plutonia that had few if any contenders in the community back then. We're a decade-and-a-half off from projects like Doom the Way id Did, after all, and these time-saving homages to the original games came in clutch for the project.

Some make this more obvious than others, like the utterly chaotic, classic slaughtermap remix of MAP01: Entryway from Doom II. This new creation, Go 2 It, even seems at odds with the spare monster placement and emphasis on precision attrition Plutonia's advocated for up until now. Hundreds of baddies swarm the bones of an opening stage best known then as the main multiplayer 1v1 map. Yet applying your newfound reflexes and reactions to enemy attacks makes the original slaughter experience not just viable, but fucking brilliant to play. All these funny lil' guys on screen are just going to kill each other anyway if you can juke them into hitting one another. Simple strategies lead to satisfying successes. It's more than just "git gud", as some will profess—more so getting flexible and adapting to scary but beatable challenges as you go.

Without Plutonia, I'm not sure I'd have ever gotten into Doom mapping, let alone a ton of newer fan creations both easier and harder than Final Doom. This feels like a necessary leap in complexity and player demands, one that's often a bit too harsh and formulaic yet well-meaning with how it challenges you. If Doom II proved that id's template was no fluke, and community efforts like Evilution and Memento Mori II showcased the story-/adventure-driven possibilities of new maps, then Plutonia's a necessary course correction for its time. The Casalis loved not just how they could push the engine to its theorized limits, but how they could maximize Romero & Petersen's game design for all its worth. What others see as unfair (which I occasionally agree with), I see as ascetic and utterly focused on avoiding downtime. There's just enough negative space in these maps between encounters to give you a breather, but never too much to bore.

Love Is... a compelling mixture, a chemical reaction that keeps you invested. It might get ugly and wear you down at times, yet it keeps you coming back. Sure it can be painful, as much as life ought not to. But if it helps you grow stronger, more understanding and empathetic, is that such a bad trade? I've had a healthy relationship with The Plutonia Experiment for years now, one which taught me make simple but effective moves in combat, or fun maps for my friends to play. This kind of appreciation takes time and effort; I won't fault anyone if they can't commit to it, and I recognize the privileges one might need to get this far. In the end, I like to think it's all been worth the patience. True love waits.

Love Is... the Plutonia Experiment, if I might be so bold. There's nothing but love throughout this entire mapset, a perennial standout among the classic Doom games for reasons debated to this day. For 1996, the mapping designs and concepts employed in PLUTONIA.WAD were avant-garde, yet seem very obvious and simple to modern Doom players. The Casali brothers were done playing by the rules and conventions fellow fan creators were bound to, from overt attempts at realism ("DoomCute" in today's parlage) to prizing adventuring and cheap thrills over exacting endurance tests of skill. For Dario & Milo, it was now or never to challenge, even brutalize their community. A kind of tough love, perhaps.

As a fanmade map pack turned second half of Final Doom, Plutonia serves as a necessary foil to TNT: Evilution's excesses and concessions. The Casalis bros. knew their community maps well, and had already been pushing the possibilities of the pre-source port Doom engine with solo releases like PUNISHER.WAD and BUTCHER.WAD. After id software witnessed their contributions to TNT.WAD—two of the most polished maps in that whole set, Dario's "Pharaoh" and Milo's "Heck"—they met and discussed making a whole new expansion pack to feature in Final Doom. The early maps they showed American McGee quickly became the start for Plutonia, which Dario & Milo had much less time to work on than TeamTNT had for their own mapset.

I could go further into The Plutonia Experiment's history, but Doomworld and Dario's own contributions paint more of the picture already. What you should know on a first playthrough is that one cannot just like this WAD. Nearly everyone I know in the Doom fandom either loves or hates this monument to mid-'90s FPS experimentation. It's more than reasonable to run through Plutonia on a lower difficulty since the maps are well-designed to retain their intensity and skill demands on Hurt Me Plenty at least. But the Casalis built this game as the kind of Japanese game show obstacle course any Doom player in '96 would approach with caution, if not trepidation. There's no remorse, little reprieve, and relatively few dull moments anywhere throughout Plutonia's alienating, jungle-laden mess of arenas, gauntlets, and set-pieces. Tough love indeed.

Not every level hits these marks. I can list some of my own pet-hate experiences, from the very poorly telegraphed "Indiana Jones" invisible bridge in MAP02: Well of Souls, to the cramped teleporting Archvile trap wrecking first-time players in MAP12: Speed. A couple of maps utterly put me off even now, mainly MAP20: The Death Domain (too many gotchas, not enough chances to take cover) or MAP30: Gateway to Hell (another needless tradition, the Icon of Sin finale). Otherwise, that leaves us with thirty difficult but rewarding maps combining Doom II's masterful combat design with more streamlined, less noodly levels to navigate. I think it's a winning combination, even if some 1996 contemporaries like the Memento Mori II mapset showcase prettier or more conceptually ambitious works.

One thing that absolutely works in Plutonia's favor is its difficult but fair approach to most combat scenarios. This is not anything like a Mario kaizo hack or masocore gaming in general. But you'll have every reason to approach fights strategically, using the right weapons and movement at the right time to survive. Both of the brothers prefer small but uniquely lethal combinations of monsters to the giant hordes you see in many popular maps today. Economy of design defines this set in contrast to not just Evilution, but other community-made packs from the time like Memento Mori. A single archvile, a couple revenants, and some cannon fodder imps...put them in a non-trivial space to travel around and you'll have one hell of a battle!

To this end, most maps shower you in higher-tier ammo for those upper-level weapons. Expect to learn the ins and outs of rocket launcher splash damage, or how to efficiently wield the BFG's invisible tracer spread fire. Practice hard enough and you'll get a feel for how to conserve super shotgun ammo as you mow down pinkies, or the basics of redirecting skeleton fireballs into other foes to get them infighting. The Casalis weren't making hard-ass shit for the sake of being hardasses. At a time when speedrunning demos were gaining popularity and the Doom community's skills and metagame were evolving, these two just wanted to gift everyone a bloody chocolate box for Valentine's. True love waits.

Funny thing is, these maps aren't as bizarre or off-putting as one might think, at least when you realize they're clever remixes of id's own levels! It makes sense how, with only several weeks to build and test their vanilla-compatible maps largely by themselves, the Casalis would chop up useful bits from Doom I & II for their own purposes. Milo's MAP21: Slayer is an obvious riff on 'O' of Destruction and other Romero levels, for instance, while Dario's works like MAP08: Realm liberally borrow ideas from Sandy Petersen's oft-maligned creations. This does mean the set can't be as revelatory or unique as it could have, despite some memorable new ideas like the iconic archvile maze in MAP11. Still, there's plenty of clever trope reuse all throughout Plutonia that had few if any contenders in the community back then. We're a decade-and-a-half off from projects like Doom the Way id Did, after all, and these time-saving homages to the original games came in clutch for the project.

Some make this more obvious than others, like the utterly chaotic, classic slaughtermap remix of MAP01: Entryway from Doom II. This new creation, Go 2 It, even seems at odds with the spare monster placement and emphasis on precision attrition Plutonia's advocated for up until now. Hundreds of baddies swarm the bones of an opening stage best known then as the main multiplayer 1v1 map. Yet applying your newfound reflexes and reactions to enemy attacks makes the original slaughter experience not just viable, but fucking brilliant to play. All these funny lil' guys on screen are just going to kill each other anyway if you can juke them into hitting one another. Simple strategies lead to satisfying successes. It's more than just "git gud", as some will profess—more so getting flexible and adapting to scary but beatable challenges as you go.

Without Plutonia, I'm not sure I'd have ever gotten into Doom mapping, let alone a ton of newer fan creations both easier and harder than Final Doom. This feels like a necessary leap in complexity and player demands, one that's often a bit too harsh and formulaic yet well-meaning with how it challenges you. If Doom II proved that id's template was no fluke, and community efforts like Evilution and Memento Mori II showcased the story-/adventure-driven possibilities of new maps, then Plutonia's a necessary course correction for its time. The Casalis loved not just how they could push the engine to its theorized limits, but how they could maximize Romero & Petersen's game design for all its worth. What others see as unfair (which I occasionally agree with), I see as ascetic and utterly focused on avoiding downtime. There's just enough negative space in these maps between encounters to give you a breather, but never too much to bore.

Love Is... a compelling mixture, a chemical reaction that keeps you invested. It might get ugly and wear you down at times, yet it keeps you coming back. Sure it can be painful, as much as life ought not to. But if it helps you grow stronger, more understanding and empathetic, is that such a bad trade? I've had a healthy relationship with The Plutonia Experiment for years now, one which taught me make simple but effective moves in combat, or fun maps for my friends to play. This kind of appreciation takes time and effort; I won't fault anyone if they can't commit to it, and I recognize the privileges one might need to get this far. In the end, I like to think it's all been worth the patience. True love waits.

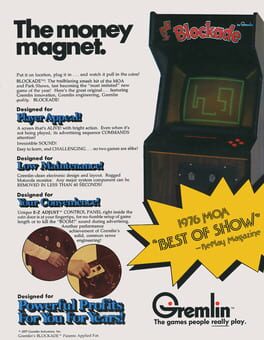

1976

Where does the versus arcade game go after Atari's Pong or Tank? Both games stuck to the ball-and-paddle paradigm in one way or another. Blockade was the solution: turn Etch-A-Sketch into an entropic competition to fill the screen. Negative space becomes the battleground for a duel of wits and reflexes, as either player tries to snake around each other without colliding. Gremlin's "money magnet" of '76 spawned a whole genre of imitators, leading to the modern snake game as popularized on Nokia phones and the Internet.

It's funny how you can't really play the original snake game, despite its outward simplicity and ease of emulation. We think of the genre today as a single-player experience when it started in the realm of 1-on-1 coin munchers. Arcade-goers still desired the kind of simple competitive pleasures Pong had provided, just with a novel game mechanic. From the moment you and your opponent start moving, with no way to stop, there's a clear, immediate tension. You're all walled in, and you've got nowhere to go but closer to your foe.

Pong, Tank, and Spacewar! before them worked because they provided the illusion of an open space you could play in, even if you either stuck to one plane of movement or had limited room for exchanging fire. I think the genius of Blockade comes from dispelling that notion entirely. You're never in any doubt about your opportunities to corner and trick the other player. And you've always got the harsh green borders of the screen to keep you focused, mentally hemmed in by the game. Clash is inevitable in this slowly filling digital world, promising not the freedom of an open space but a ruthless drive to destruction.

Today, it all seems a bit quaint. We're many decades separated from Blockade—the progenitor of not just snake games all about managing a depleting space, but the confinement of the fighting game genre too. As fast as this must have seemed in '76, it's laborious and simply dull to play today. Indeed, Gremlin engineer Lane Hauck's creation "wasn't a good game from the standpoint of making money...The industry loved Blockade but the public yawned.". Creators like him recognized the sea change this game proved was feasible, though. It wouldn't be long before Disney's TRON demonstrated how exciting this concept could be. Moreover, Blockade's success with operators showed that Tank was no fluke, that plenty of multiplayer dueling concepts beyond the ball and paddle were not just viable, but desirable.

All in all, I can't really hold much against a game that did well enough to get clones with names like Bigfoot Bonkers. I'd have never grown up chomping down every little dot on my flip-phone LCD screen were it not for this. (Hell, where would Head-On or Pac-Man be if Blockade hadn't paved the way?!) Of their pre-SEGA achievements, Gremlin's original screen filler has earned its place in arcade game history.

It's funny how you can't really play the original snake game, despite its outward simplicity and ease of emulation. We think of the genre today as a single-player experience when it started in the realm of 1-on-1 coin munchers. Arcade-goers still desired the kind of simple competitive pleasures Pong had provided, just with a novel game mechanic. From the moment you and your opponent start moving, with no way to stop, there's a clear, immediate tension. You're all walled in, and you've got nowhere to go but closer to your foe.

Pong, Tank, and Spacewar! before them worked because they provided the illusion of an open space you could play in, even if you either stuck to one plane of movement or had limited room for exchanging fire. I think the genius of Blockade comes from dispelling that notion entirely. You're never in any doubt about your opportunities to corner and trick the other player. And you've always got the harsh green borders of the screen to keep you focused, mentally hemmed in by the game. Clash is inevitable in this slowly filling digital world, promising not the freedom of an open space but a ruthless drive to destruction.

Today, it all seems a bit quaint. We're many decades separated from Blockade—the progenitor of not just snake games all about managing a depleting space, but the confinement of the fighting game genre too. As fast as this must have seemed in '76, it's laborious and simply dull to play today. Indeed, Gremlin engineer Lane Hauck's creation "wasn't a good game from the standpoint of making money...The industry loved Blockade but the public yawned.". Creators like him recognized the sea change this game proved was feasible, though. It wouldn't be long before Disney's TRON demonstrated how exciting this concept could be. Moreover, Blockade's success with operators showed that Tank was no fluke, that plenty of multiplayer dueling concepts beyond the ball and paddle were not just viable, but desirable.

All in all, I can't really hold much against a game that did well enough to get clones with names like Bigfoot Bonkers. I'd have never grown up chomping down every little dot on my flip-phone LCD screen were it not for this. (Hell, where would Head-On or Pac-Man be if Blockade hadn't paved the way?!) Of their pre-SEGA achievements, Gremlin's original screen filler has earned its place in arcade game history.

2003

Credit where it's due: at least the Game Boy Camera and SEGA's DreamEye got treated with enough dignity to never suffer a minigame collection this lame.

More credit goes to London Studio for injecting some much-needed, if dated amount of personality where it counts. I'll always fondly remember unpacking this honestly not terrible webcam (Logitech wasn't much better in '03), then loading into the cheeky, very post-Psygnosis tutorial movie explaining how to use the peripheral. Watching what might as well be the queen mother and her clones dancing to stock library disco as the Stanley Parable narrator goodbye-s you is still surreal. I wish the game itself had as much family-friendly anarchy. Part of me wants to argue the inconsistent art direction between minigames brings this closer to WarioWare or a modern game jam, but it's just not there.

With 12 minigames of varying quality on offer, Sony's making a go at matching its competitors in silly gimmickry. A good chunk of the experience revolves around variations on whack-a-mole, or something like those Moorhuhn (Crazy Chicken) shovelware titles you see every now and then. This whole idea of pairing a novel, limited but intriguing add-on console toy with what amounts to a prototype Carnival Games worked at the time. The folks & I had a solid time looking stupid in front of the TV, though my sister stuck mostly to our metal DDR pad since those games had far more substance. Little did we know this would have us wibblin' and wobblin' in the living room some years later—that was Wii Sports, though, which remains far more replayable in 2023.

EyeToy Play is fun enough for what it is, a serviceable pack-in game which took the safe route with proving that this idea could even work. Nintendo's aforementioned handheld lens toy has somehow managed to age better by dint of offering a uniquely lo-fi experience, though. Going from harsh but exotic monochrome games and photo printing to the blurry, often out-of-focus mess EyeToy provides seems a bit underwhelming nowadays. What I really lament, though, is the C-rate Y2K aesthetic dominating this collection. (Half of the game looks like it's recycling unused Psybadek concepts, mashing them up with Gorillaz and other post-Y2K intercontinental mascot designs.) It just reminds me too much of when these developers, a mix of ex-Psygnosis fellas and The Getaway's team, had more creative projects to work on.

Again, this isn't a strictly bad game. Most minigames work properly with the EyeToy in most room settings, and it's a bit amusing to wave your arms around, a kind of bastardized ParaPara Paradise or Samba de Amigo for the new era. Just temper your expectations if you collect one of these square, googly things and stick this in your PS2. I'd personally rather play SEGA Superstars if only for the IP variety and actual Samba de Amigo experience. However, the lack of ambition and increasingly quaint presentation behind this pack-in was kind of the point. If it was too good a free disc to keep playing, would you have bought all those other EyeToy games coming later? Consider how Nintendo fell into that trap later, with Wii Sports & Play offering enough for most owners to just skip out on following minigame collections (or settle for the bargain bin equivalents).

See, this is exactly what Thursday does to an oldhead like me. I get vaguely nostalgic thoughts about what passed muster for party night amusement at the end of elementary school, and then I think harder about what this was actually like. Youngsters have it so much easier in these social media dog days. EyeToy: Play was the offline TikTok dance simulator of its day, cheaper than a ParaPara cab every weekend but not much more advanced than some plastic maracas. Games like this fall through the cracks of half-remembered cringe and convenient historic amnesia—some would say for the better. I just feel sorry for all the UK devs Sony chopped into teams like London Studio, who then had to take any mid project they could get by their corporate sponsor. tl;dr Where the hell's the Wipeout minigame in this set?!

More credit goes to London Studio for injecting some much-needed, if dated amount of personality where it counts. I'll always fondly remember unpacking this honestly not terrible webcam (Logitech wasn't much better in '03), then loading into the cheeky, very post-Psygnosis tutorial movie explaining how to use the peripheral. Watching what might as well be the queen mother and her clones dancing to stock library disco as the Stanley Parable narrator goodbye-s you is still surreal. I wish the game itself had as much family-friendly anarchy. Part of me wants to argue the inconsistent art direction between minigames brings this closer to WarioWare or a modern game jam, but it's just not there.

With 12 minigames of varying quality on offer, Sony's making a go at matching its competitors in silly gimmickry. A good chunk of the experience revolves around variations on whack-a-mole, or something like those Moorhuhn (Crazy Chicken) shovelware titles you see every now and then. This whole idea of pairing a novel, limited but intriguing add-on console toy with what amounts to a prototype Carnival Games worked at the time. The folks & I had a solid time looking stupid in front of the TV, though my sister stuck mostly to our metal DDR pad since those games had far more substance. Little did we know this would have us wibblin' and wobblin' in the living room some years later—that was Wii Sports, though, which remains far more replayable in 2023.

EyeToy Play is fun enough for what it is, a serviceable pack-in game which took the safe route with proving that this idea could even work. Nintendo's aforementioned handheld lens toy has somehow managed to age better by dint of offering a uniquely lo-fi experience, though. Going from harsh but exotic monochrome games and photo printing to the blurry, often out-of-focus mess EyeToy provides seems a bit underwhelming nowadays. What I really lament, though, is the C-rate Y2K aesthetic dominating this collection. (Half of the game looks like it's recycling unused Psybadek concepts, mashing them up with Gorillaz and other post-Y2K intercontinental mascot designs.) It just reminds me too much of when these developers, a mix of ex-Psygnosis fellas and The Getaway's team, had more creative projects to work on.

Again, this isn't a strictly bad game. Most minigames work properly with the EyeToy in most room settings, and it's a bit amusing to wave your arms around, a kind of bastardized ParaPara Paradise or Samba de Amigo for the new era. Just temper your expectations if you collect one of these square, googly things and stick this in your PS2. I'd personally rather play SEGA Superstars if only for the IP variety and actual Samba de Amigo experience. However, the lack of ambition and increasingly quaint presentation behind this pack-in was kind of the point. If it was too good a free disc to keep playing, would you have bought all those other EyeToy games coming later? Consider how Nintendo fell into that trap later, with Wii Sports & Play offering enough for most owners to just skip out on following minigame collections (or settle for the bargain bin equivalents).

See, this is exactly what Thursday does to an oldhead like me. I get vaguely nostalgic thoughts about what passed muster for party night amusement at the end of elementary school, and then I think harder about what this was actually like. Youngsters have it so much easier in these social media dog days. EyeToy: Play was the offline TikTok dance simulator of its day, cheaper than a ParaPara cab every weekend but not much more advanced than some plastic maracas. Games like this fall through the cracks of half-remembered cringe and convenient historic amnesia—some would say for the better. I just feel sorry for all the UK devs Sony chopped into teams like London Studio, who then had to take any mid project they could get by their corporate sponsor. tl;dr Where the hell's the Wipeout minigame in this set?!

1980

tim rogers voice I Was a Sierra On-Line Poser smashes keyboard on stage and plays foosball with the keycaps

Like many others who love media history but struggle to get into or make time for certain parts of it, the formative parser-driven adventure games like Wander, Colossal Cave Adventure, and Sierra On-Line's classics like Mystery House have eluded me. But I'm also guilty of just not going for them like a hunter chases flock, or a prospector dives for gold. To have this apathy, despite knowing pretty much all these games are easily playable on Internet Archive, ate at me until recently. Something's clicked—probably just the satisfaction of completing Myst last month after years of never clearing the first island. But that's enough to get me committed to trying these ramshackle first attempts at conjuring immersive worlds on the earliest home computer platforms.

Mission Asteroid had a simple, er, mission: introduce any and all possible Apple II users to the graphic text adventure. Roberta Williams knew this didn't have to be as intricate as her Agatha Christie-esque first game, nor as fanciful as The Wizard and the Princess. A solid, pulp-y "save the Earth!" story could get you used to the studio's text parser, thinking up valid verb combinations, and managing your time and patience wisely. No matter how much this game continues to age like an indescribable beverage, it still fulfills those criteria. That's a nice way of saying this 1980 release had much less bullshit puzzling and navigation than its peers.

What the Williams duo would have called "simple" or "entry-level" then is considered hard to parse today dodges tomatoes after that pun. You've got the usual N-S-E-W compass commands, sure, but also instances of having to enter door rather than just go north through it. The two-word restriction on your interactions becomes painfully clear when trying to do something as straightforward as insert a floppy disk into the mission HQ Apple II. You type take disk, carriage return, and then insert disk (repeat), only for the game to ask where you're inserting this thing. There's no death branch here if you specify the wrong target or anything, just needless busywork compounded by the parser system.

Yet, for all the grief these simplistic parsers give me, there's still the fun of tinkering with what hidden-in-plain-sight options you can type in. All the gizmos in your space rocket can either doom you or take you on a disorienting ride through Earth orbit, controlled only by your type-in commands. Wandering the asteroid itself becomes a tense adventure as you likely know from harsh experience that the air supply's time-limited. Once the game lifts its tutorializing gaze from you, Mission Asteroid feels like an organic interplay between you, the reader asking questions, and the ghost of a game master hiding in the machine. It's easier now to see how Roberta, Ken, and others who'd soon join On-Line Systems could champion this genre framework.

Obviously there's not much to look at in this now, with its rudimentary VersaWriter drawings and lack of sound design. At the end of the day, most of the puzzles are either too simple to satisfy or convoluted enough to irritate me a bit too much. But I can gladly say that Mission Asteroid's an easier way to start playing turn-of-the-'80s graphic text stories than I've been told. It gets you into the necessary frame of mind with relatively little condescending scenarios or design language. The truly brutal riddles and cat's cradles of contemporary text adventures are reduced in scope, tightening up the pace. One gets to have a just-filling-enough time with the genre here before it overstays its welcome, either by avoiding a glut of bad ends or treating the player's time with more respect. I sense and can only speculate that Roberta's need to finish this romp for the holidays, capitalizing on Mystery House's success, left less room for potentially harmful experiments or indulgence.

So it's the definition of mid, yet I can't hold that against this game in retrospect. There's much worse one could try from that era, ranging from Scott Adams' pioneering all-text enigmas to their slapdash imitators on TRS-80 or Commodore PET (take your pick of PC cheaper than the Apple ][+). Given how Mission Asteroid itself avoids some of the amateur mistakes in Mystery House I hear about, I'm not content slapping this with a 2-star and calling it there. Whether or not it's a labor of love on par with Sierra On-Line's adventures soon to come, this little ditty of a day's work blowing up an asteroid punches above its weight class where it counts. Some higher being oughta know we got more than we asked for when Michael Bay's people adapted the premise almost two decades later. Keep it simple, Sierra!

Like many others who love media history but struggle to get into or make time for certain parts of it, the formative parser-driven adventure games like Wander, Colossal Cave Adventure, and Sierra On-Line's classics like Mystery House have eluded me. But I'm also guilty of just not going for them like a hunter chases flock, or a prospector dives for gold. To have this apathy, despite knowing pretty much all these games are easily playable on Internet Archive, ate at me until recently. Something's clicked—probably just the satisfaction of completing Myst last month after years of never clearing the first island. But that's enough to get me committed to trying these ramshackle first attempts at conjuring immersive worlds on the earliest home computer platforms.

Mission Asteroid had a simple, er, mission: introduce any and all possible Apple II users to the graphic text adventure. Roberta Williams knew this didn't have to be as intricate as her Agatha Christie-esque first game, nor as fanciful as The Wizard and the Princess. A solid, pulp-y "save the Earth!" story could get you used to the studio's text parser, thinking up valid verb combinations, and managing your time and patience wisely. No matter how much this game continues to age like an indescribable beverage, it still fulfills those criteria. That's a nice way of saying this 1980 release had much less bullshit puzzling and navigation than its peers.

What the Williams duo would have called "simple" or "entry-level" then is considered hard to parse today dodges tomatoes after that pun. You've got the usual N-S-E-W compass commands, sure, but also instances of having to enter door rather than just go north through it. The two-word restriction on your interactions becomes painfully clear when trying to do something as straightforward as insert a floppy disk into the mission HQ Apple II. You type take disk, carriage return, and then insert disk (repeat), only for the game to ask where you're inserting this thing. There's no death branch here if you specify the wrong target or anything, just needless busywork compounded by the parser system.

Yet, for all the grief these simplistic parsers give me, there's still the fun of tinkering with what hidden-in-plain-sight options you can type in. All the gizmos in your space rocket can either doom you or take you on a disorienting ride through Earth orbit, controlled only by your type-in commands. Wandering the asteroid itself becomes a tense adventure as you likely know from harsh experience that the air supply's time-limited. Once the game lifts its tutorializing gaze from you, Mission Asteroid feels like an organic interplay between you, the reader asking questions, and the ghost of a game master hiding in the machine. It's easier now to see how Roberta, Ken, and others who'd soon join On-Line Systems could champion this genre framework.

Obviously there's not much to look at in this now, with its rudimentary VersaWriter drawings and lack of sound design. At the end of the day, most of the puzzles are either too simple to satisfy or convoluted enough to irritate me a bit too much. But I can gladly say that Mission Asteroid's an easier way to start playing turn-of-the-'80s graphic text stories than I've been told. It gets you into the necessary frame of mind with relatively little condescending scenarios or design language. The truly brutal riddles and cat's cradles of contemporary text adventures are reduced in scope, tightening up the pace. One gets to have a just-filling-enough time with the genre here before it overstays its welcome, either by avoiding a glut of bad ends or treating the player's time with more respect. I sense and can only speculate that Roberta's need to finish this romp for the holidays, capitalizing on Mystery House's success, left less room for potentially harmful experiments or indulgence.

So it's the definition of mid, yet I can't hold that against this game in retrospect. There's much worse one could try from that era, ranging from Scott Adams' pioneering all-text enigmas to their slapdash imitators on TRS-80 or Commodore PET (take your pick of PC cheaper than the Apple ][+). Given how Mission Asteroid itself avoids some of the amateur mistakes in Mystery House I hear about, I'm not content slapping this with a 2-star and calling it there. Whether or not it's a labor of love on par with Sierra On-Line's adventures soon to come, this little ditty of a day's work blowing up an asteroid punches above its weight class where it counts. Some higher being oughta know we got more than we asked for when Michael Bay's people adapted the premise almost two decades later. Keep it simple, Sierra!

Whoever escaped the Abenomics-era Konami developer prison to make this and keep it mostly ad-free for a couple of years: I salute you. May your cockles be warm and your curry plate tasty.

Jupiter took their precious sweet time doing more Picross collabs with IPs from corps like SEGA, yet the company no one expected put this out for free. And it barely feels like a free-to-play monstrosity, either! I picked up Pixel Puzzle Collection back around release since I wanted a meaty mobile game for the road, but got plenty more than I'd hoped for. There's a decades-spanning rogues' gallery of cool references made into nonograms here, from Frogger to Tokimeki Memorial. Playing these in a randomized sequence, albeit tuned for difficulty, makes it a smooth stop-and-go experience. I didn't realize that I'd gotten far into the total puzzles list until reaching the first batch of big multi-piece pictures, a good sign if ever.

UI and touch precision responsiveness are everything in a mobile nonogram app like this. I'm happy to report that, while a little stiff at times, this still feels better to use than the much bigger, easily discoverable competitors on the iOS marketplace. It rarely feels like I'm fat-fingering myself into a misplaced pip I'll regret later, or that I can't quickly redo grid sections when needed. This matters once you reach the game's second loop (its "Hard Mode"), where the inability to mark X pips means you must fill each line more carefully. After all, how am I gonna make my Shiori Fujisaki solutions come true if I keep messing up thirty minutes back?! (That's still more generous than the games she's from, no doubt.)

Pixel Puzzle Collection feels like an M2 employee's pet project at times, the kind of passionate mega-mini-game you'd make in the shadows and then slap into one of their compilations like it's nothing. This stood out five years ago mainly because it stood against all the stereotypes Konami's earned in recent years, most of which oppose that which this Picross set exalts. It's telling how classic Hudson Soft icons and characters from many games share plenty of space with the core Konami crew, as the corporation had become awfully good at erasing Hudson's history from digital stores by this point. There's nothing quite like hopping from Ganbare Goemon to Star Solider in a moment's notice, let's just put it that way.

For less experienced nonogram heads, there's a smartly designed hint system in play here. You get three daily solutions to use for any puzzle (plus the add for "boss" grids), and then a 10-minute cooldown for each new one after those. I like this more than the overly generous equivalents I see on my other phone Picross apps, and it feels naturally tuned to how much attention I'd give a hard puzzle before moving on. All I want now is more, which I guess is too much for Konami since they've done nothing for Pixel Puzzle Collection these past few years except shove more ads in. They really want you playing any other mobile game that could squeeze more coin, as if a prestige experience like this is somehow hurting their bottom line enough to deserve such harm. I hope whoever coded/designed the game is having an alright time, wherever they are.

All this sounds frustrating and it is when you consider how well Nintendo treats Jupiter's Picross works. Even then, the official Picross games you can get on the eShop now feel creatively stagnant, or just unwilling to toy with riskier concepts like that company used to. I'm not saying this weird misbegotten Konami counterpart is innovative, either, but it had so much sequel potential that's just getting squandered over time. Indie scene developers are taking the genre in all sorts of new directions while those who can access the kinds of resources Nintendo & Konami have are getting screwed. And I find it harder to recommend Pixel Puzzle Collection now because, while the core game's unchanged, all the new ads and annoyances remind you of what could have been. But I think it's still an easy choice for game fans who are either into nonograms or could use a cute diversion playing on nostalgia without feeling like a copout.

Jupiter took their precious sweet time doing more Picross collabs with IPs from corps like SEGA, yet the company no one expected put this out for free. And it barely feels like a free-to-play monstrosity, either! I picked up Pixel Puzzle Collection back around release since I wanted a meaty mobile game for the road, but got plenty more than I'd hoped for. There's a decades-spanning rogues' gallery of cool references made into nonograms here, from Frogger to Tokimeki Memorial. Playing these in a randomized sequence, albeit tuned for difficulty, makes it a smooth stop-and-go experience. I didn't realize that I'd gotten far into the total puzzles list until reaching the first batch of big multi-piece pictures, a good sign if ever.

UI and touch precision responsiveness are everything in a mobile nonogram app like this. I'm happy to report that, while a little stiff at times, this still feels better to use than the much bigger, easily discoverable competitors on the iOS marketplace. It rarely feels like I'm fat-fingering myself into a misplaced pip I'll regret later, or that I can't quickly redo grid sections when needed. This matters once you reach the game's second loop (its "Hard Mode"), where the inability to mark X pips means you must fill each line more carefully. After all, how am I gonna make my Shiori Fujisaki solutions come true if I keep messing up thirty minutes back?! (That's still more generous than the games she's from, no doubt.)

Pixel Puzzle Collection feels like an M2 employee's pet project at times, the kind of passionate mega-mini-game you'd make in the shadows and then slap into one of their compilations like it's nothing. This stood out five years ago mainly because it stood against all the stereotypes Konami's earned in recent years, most of which oppose that which this Picross set exalts. It's telling how classic Hudson Soft icons and characters from many games share plenty of space with the core Konami crew, as the corporation had become awfully good at erasing Hudson's history from digital stores by this point. There's nothing quite like hopping from Ganbare Goemon to Star Solider in a moment's notice, let's just put it that way.

For less experienced nonogram heads, there's a smartly designed hint system in play here. You get three daily solutions to use for any puzzle (plus the add for "boss" grids), and then a 10-minute cooldown for each new one after those. I like this more than the overly generous equivalents I see on my other phone Picross apps, and it feels naturally tuned to how much attention I'd give a hard puzzle before moving on. All I want now is more, which I guess is too much for Konami since they've done nothing for Pixel Puzzle Collection these past few years except shove more ads in. They really want you playing any other mobile game that could squeeze more coin, as if a prestige experience like this is somehow hurting their bottom line enough to deserve such harm. I hope whoever coded/designed the game is having an alright time, wherever they are.

All this sounds frustrating and it is when you consider how well Nintendo treats Jupiter's Picross works. Even then, the official Picross games you can get on the eShop now feel creatively stagnant, or just unwilling to toy with riskier concepts like that company used to. I'm not saying this weird misbegotten Konami counterpart is innovative, either, but it had so much sequel potential that's just getting squandered over time. Indie scene developers are taking the genre in all sorts of new directions while those who can access the kinds of resources Nintendo & Konami have are getting screwed. And I find it harder to recommend Pixel Puzzle Collection now because, while the core game's unchanged, all the new ads and annoyances remind you of what could have been. But I think it's still an easy choice for game fans who are either into nonograms or could use a cute diversion playing on nostalgia without feeling like a copout.

1995

Gotta see some games to believe 'em, and this might well be the most pop art looking-ass OutRun clone in existence. It's the spitting image of what an indie take on AM2's classic with Atari 2600 graphics could resemble today. Bio_100% (programmer "metys" specifically) first distributed this in 1994 across various Japanese BBS networks before the final version arrived a year later, both online and via shareware collections. Playing any racer this fast, arcade-y, and devil-may-care on an aging PC-98 platform must have been a revelation.

No one's gonna fool themselves into deeming this a realistic driving sim(-cade) experience, and it's better off for that. Polestar's got the kind of DIY spirit and a style all its own that newer takes on classic Super Scaler racers could learn from. You've got two sets of increasingly complex circuits to lap, a sleek sports car to learn the handling of, and the most uncanny, smoothly performing arts-and-crafts visual style I've seen in this genre. It's all clearly working within the boundaries of what a primarily text & static graphics-focused system can do best. And I love that kind of platform-pushing pride which acknowledges the limits of the PC-98 (let alone other home computers back then) but leads to seemingly impossible achievements anyway.

This short but sweet game runs best at on 486 chips running 20 MHz or more, a rather low figure which many users reached or exceeded, so it managed all its feats without becoming the Crysis of its community. Controls are the standard but responsive pedal, brake, and low-to-high shifter seen in OutRun and countless titles like it. What's nice is the detailed options/configuration screen Bio_100% provides, letting you change everything from the measurement system to in-game FOV! There's just enough customization here to compensate for a lack of extra vehicles, plus the low amount of content and novel replayability. It's also a rare later game to only use PSG or MIDI music, forgoing the PC-98's usual FM-synth sound chip even at the expense of some players. (Then again, never a better time to slap Tatsuro Yamashita in your Walkman.)

Simple keyboard & gamepad commands, plus ways to achieve a solid 60 FPS feeling even on 25 KHz refresh monitors, all fortify Polestar's gamefeel. Getting used to the game's sometimes slipper road physics can take a couple tries, but comes naturally over time. You're sharing lanes with hazards like errant trucks and breaks in the pavement; avoiding any off-roading when crossing water or passing by a big creepy clown animatronic (among other things) gives you plenty of challenge. But like any arcade auto-sseys worth a damn, you're mostly racing the time limit and your past records, zipping around with glee as the numbers tick up. There's not a whole lot for me to say here except that metys and his Bio_100% collaborators loved their classic racers and effortlessly brought the genre's strengths to an unlikely venue.

At this point in the PC-98's lifecycle, Windows 95 was beginning its reign of terror upon the once relatively isolated Japanese PC market. Commercial game makers either tried to work with Microsoft's initial, admittedly shoddy development tools for the new OS, or they bailed on their PC strongholds to find success on consoles instead. This left a big variety gap for doujin creators like metys, a coder accustomed to working remotely over BBS and now the Internet. Whether creating for the whole online country or just Comiket runs, Japan's changing PC gaming landscape behooved smaller, less financially bound game makers to pick up where studios like Telenet and Micro Cabin left off. Bio_100%'s renown in the doujin freeware space reached its peak at the middle of the decade, and Polestar represents this in so many ways.

Above all, it's rare to play an arcade-style racer this imbued with a bubble-era ethos and optimism, yet staunchly opposed to commercialization and any related baggage. So many players invested in the PC-98 could dial up their local ASCII net, pay much less to download this than even a Takeru vending-machine floppy game, and have a nightly favorite running on their turn-of-the-'90s PC within a day. The slow but sure democratization of online networking and doujin free-/shareware in mid-'90s Japan did wonders to buoy an ecosystem transitioning from one dominant power, NEC, to another under Windows. Polestar may not have a hydraulic taikan cabinet with cool gizmos, nor a bevy of extra tracks like you'd expect from the hot new racers on PS1 & Saturn. But with all else it offers at such high quality, it filled a niche in that special way only Bio_100% and a few other doujin creators could at the time. Perhaps a certain Team Shanghai Alice learned a thing or two from this group's smart decisions.

Like with most Bio_100% releases from '90-'96, Polestar's easily accessible via PC-98 emulator running either the floppies or a multi-game compilation. Jumping between this and the group's earlier, rougher but similarly joyful titles makes it even easier to appreciate what the '94 racer accomplished. It's a shame how the group basically died down and soon disbanded as Windows really took over, with Bio_100% creators moving further into their careers away from doujin development. But if that meant ending on such a high note between this and Sengoku TURB for Dreamcast, then I can't complain much. Polestar's a sporty circuit racer for the people, and one of the best PC-98 games you can just jump into right now, no extra work or mental prep required.

No one's gonna fool themselves into deeming this a realistic driving sim(-cade) experience, and it's better off for that. Polestar's got the kind of DIY spirit and a style all its own that newer takes on classic Super Scaler racers could learn from. You've got two sets of increasingly complex circuits to lap, a sleek sports car to learn the handling of, and the most uncanny, smoothly performing arts-and-crafts visual style I've seen in this genre. It's all clearly working within the boundaries of what a primarily text & static graphics-focused system can do best. And I love that kind of platform-pushing pride which acknowledges the limits of the PC-98 (let alone other home computers back then) but leads to seemingly impossible achievements anyway.

This short but sweet game runs best at on 486 chips running 20 MHz or more, a rather low figure which many users reached or exceeded, so it managed all its feats without becoming the Crysis of its community. Controls are the standard but responsive pedal, brake, and low-to-high shifter seen in OutRun and countless titles like it. What's nice is the detailed options/configuration screen Bio_100% provides, letting you change everything from the measurement system to in-game FOV! There's just enough customization here to compensate for a lack of extra vehicles, plus the low amount of content and novel replayability. It's also a rare later game to only use PSG or MIDI music, forgoing the PC-98's usual FM-synth sound chip even at the expense of some players. (Then again, never a better time to slap Tatsuro Yamashita in your Walkman.)

Simple keyboard & gamepad commands, plus ways to achieve a solid 60 FPS feeling even on 25 KHz refresh monitors, all fortify Polestar's gamefeel. Getting used to the game's sometimes slipper road physics can take a couple tries, but comes naturally over time. You're sharing lanes with hazards like errant trucks and breaks in the pavement; avoiding any off-roading when crossing water or passing by a big creepy clown animatronic (among other things) gives you plenty of challenge. But like any arcade auto-sseys worth a damn, you're mostly racing the time limit and your past records, zipping around with glee as the numbers tick up. There's not a whole lot for me to say here except that metys and his Bio_100% collaborators loved their classic racers and effortlessly brought the genre's strengths to an unlikely venue.

At this point in the PC-98's lifecycle, Windows 95 was beginning its reign of terror upon the once relatively isolated Japanese PC market. Commercial game makers either tried to work with Microsoft's initial, admittedly shoddy development tools for the new OS, or they bailed on their PC strongholds to find success on consoles instead. This left a big variety gap for doujin creators like metys, a coder accustomed to working remotely over BBS and now the Internet. Whether creating for the whole online country or just Comiket runs, Japan's changing PC gaming landscape behooved smaller, less financially bound game makers to pick up where studios like Telenet and Micro Cabin left off. Bio_100%'s renown in the doujin freeware space reached its peak at the middle of the decade, and Polestar represents this in so many ways.

Above all, it's rare to play an arcade-style racer this imbued with a bubble-era ethos and optimism, yet staunchly opposed to commercialization and any related baggage. So many players invested in the PC-98 could dial up their local ASCII net, pay much less to download this than even a Takeru vending-machine floppy game, and have a nightly favorite running on their turn-of-the-'90s PC within a day. The slow but sure democratization of online networking and doujin free-/shareware in mid-'90s Japan did wonders to buoy an ecosystem transitioning from one dominant power, NEC, to another under Windows. Polestar may not have a hydraulic taikan cabinet with cool gizmos, nor a bevy of extra tracks like you'd expect from the hot new racers on PS1 & Saturn. But with all else it offers at such high quality, it filled a niche in that special way only Bio_100% and a few other doujin creators could at the time. Perhaps a certain Team Shanghai Alice learned a thing or two from this group's smart decisions.

Like with most Bio_100% releases from '90-'96, Polestar's easily accessible via PC-98 emulator running either the floppies or a multi-game compilation. Jumping between this and the group's earlier, rougher but similarly joyful titles makes it even easier to appreciate what the '94 racer accomplished. It's a shame how the group basically died down and soon disbanded as Windows really took over, with Bio_100% creators moving further into their careers away from doujin development. But if that meant ending on such a high note between this and Sengoku TURB for Dreamcast, then I can't complain much. Polestar's a sporty circuit racer for the people, and one of the best PC-98 games you can just jump into right now, no extra work or mental prep required.

2000

One of those epochal clashes between dirty, abrasive, endearing eco-romance and cute, sinister Y2K-era techno-optimism turned satire of imperialism. These angles lock arms in a subtle but ever-looming creation story of what video games, as puzzle boxes and a storytelling medium, could become in the new millennium. Love-de-Lic finally mastered this kind of anti-RPG disguising a clever adventure, and L.O.L's occasional flaws rarely distract from the majesty and sheer emotional gamut this offers. Here's a Gaia of broken promises, uprooted existence, twisted social covenants, and how to survive and adapt in a harsh universe where we're the only love we give.

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Jan. 31 – Feb. 6, 2023

If Moon RPG was a thesis polemic and UFO a dissertation, then Lack of Love was Kenichi Nishii & co.'s post-doctorate trial by fire. The era of overly experimental, often commercially unviable projects like this on PlayStation, SEGA Saturn, and now Dreamcast was slowly in decline. Almost all the post-bubble era investment capital needed to support teams like them would filter increasingly into stable, more conservative groups and companies working on console games. In a sense, they saw themselves as a dying breed, the kind that gets stomped all over in this year-2000 cautionary tale. I'm just glad Ryuichi Sakamoto helped produce this and get it to market, especially given the system's poor performance in Japan. His music and environmentalist/anti-capitalist stance stick out at times throughout the story, but he's mainly taking a backseat and giving Love-de-Lic their last chance to create something this ambitious together. In all the years since, the studio's staff diaspora has led to countless other notable works, and parts of L.O.L. both hint at those while revealing what was lost.

We're far from Chibi-Robo or the Tingle spinoffs here, after all. Lack of Love shows unwavering confidence in the player's ability to roleplay as this evolving, invisibly sentient creature who experiences many worlds on one planet, both native and invasive. Every real or fake ecosystem we travel to, whether by accident or in search of respite, offers enough challenge, task variation, and indulgent audiovisuals to keep one going. I wish I could say that for more players, though. It might not reach the difficulty and obtuseness of much older graphic adventures from the Sierra and Infocom glory years, but I've seen enough people who like classic games bounce off this one to know it's a hard ask. You have no choice but to poke, prod, and solve each environment with verbs you'd normally never consider, such as simply sleeping in a spot for longer than feels comfortable or, well, interesting. It's more than beatable, but I won't begrudge anyone for watching this or relying on a walkthrough. LDL designed L.O.L to be dissected, not gulped down. Tellingly, though, the game starts and ends with a titanic beast possibly devouring you unless you act quickly, instinctively perhaps.

One moment that frustrated me, but also revealed the genius behind it all, was trying to race the bioluminescent flyers on level 5. By this point I've transformed a few times, having become a frilly flightless fellow with plenty of brawn and speed. Darting across this mixture of bizarre swamp, desert, and grassland terrain has led to what feels like a softlock, a set of plant walls I can only squeeze by if I use the right tool. Lack of Love succeeds in telegraphing points of interest for most puzzles, be it the obvious dirt starting line for the night races in this grove, or the cold and minimalistic off-world objects and structures seen later. What's never as obvious is how exactly to interact with other creatures for more complex tasks. Helping out by killing a larger bully or retrieving a parent's lost child is straightforward, but something as simple as just entering the race used a good hour of my time here. Oh sure, I could win the race all right…but it took way too long for the game to recognize and reward me, forcing another long wait from night to day and back again since there's only one lap a cycle.

I recognize that my impatience got in the way of just accepting this, one of life's many setbacks. So I simply waited all day and half a night to repeat the ritual until I got it right. A majority of L.O.L's dialogue with players and critics comes down to how it considers rituals, those habits justified & unjustified which define our daily lives. If anything, the interrogation of normalized behaviors, and the true intentions or lack of them hiding behind, define the studio's short career. As I gorged on helmet-headed stilt walkers and headbutted tree-nuts to slurp up their fruit, it dawned on me how well this game handles repetition. Many times did I get entranced into calling, roaring, and pissing all over each map to see if some cool event or interaction could happen where it'd make sense. Most of these levels are well-built for quickly crossing from one relevant hotspot to another. That desire to see it all through, no matter when I got humiliated or had to slog past something I'd solved but failed to do just right at just the right moment…it makes all of this worthwhile.

Progression throughout Lack of Love isn't usually this janky or unintuitive though. The game's main advancement system, the psychoballs you collect to activate evolution crystals, accounts for skipping the befriending process with some of your neighbors. It makes this a bit more replayable than usual for the genre, as you can leave solving the tougher riddles to a repeat run while continuing onward. I wish there wasn't anything as poorly built as this firefly race, or the somewhat tedious endgame marathon where your latest form can't run. But while that impedes the game's ambitions somewhat, it usually isn't a dealbreaker. LDL's crafted an impressive journey out of life's simplest moments, pleasures, and triumphs over adversity, from your humble start inside a hollow tree to the wastes of what the eponymous human resettling project has wrought. There's only a few "special" moves you can learn, from dashing to

In short, L.O.L. is a study of contrasts: the precious, vivacious yet forever dangerous wilds of this planet vs. the simpler, stable yet controlling allure of organized systems and societies. Nothing ever really works out in nature, not even for the apex predators like me. Yet everything has to work according to some plan or praxis in any form of civilization, something made possible through explicit communication. Love de Lic's challenge was to treat players with as much respect for their intelligence as possible before giving them something inscrutable—no straight line to triumph. This game had to feel alien, but still somehow understandable for its themes and messages to resonate. It's an unenviable goal for most developers. Just ask former LDL creators who have moved on to more manageable prospects. Obscurantism is a mixed blessing all throughout the experience, and I can't imagine this game any other way.

The opening level at least prepares you for the long, unwieldy pilgrimage to enlightenment through a few key ways. Popping out of the egg, swimming to shore, and the camera panning over a creature evolving via silver crystals gives a starting push. Then there's the initial "call for help", a newborn creature struggling to get up. Getting your first psychoball requires not aggression, but compassion for other ingenues like you. On the flipside, you end up having to kill a predator much larger and stronger than yourself, just to save harmless foragers. I definitely wish the game did a better job of avoiding this Manichean binary for more of the psychoball challenges, but it works well this early on. Maybe the initially weird, highly structured raise-the-mush-roof puzzle west of start was a hint of more involved sequences either planned or cut down a bit

Crucially, the following several stages demonstrate how Lack of Love's alien earth is far from some arcadian paradise. The game simply does not judge you for turning traitor and consuming the same species you just helped out; regaining their trust is usually just as easy. One look at the sun-cracked, footstep-ravaged wasteland outside your cradle portends further ordeals. LDL still wants you to succeed, however. The start menu offers not only maps + your current location for most levels, but a controls how-to and, most importantly, a bestiary screen. It's here where each character's name offers some hint, small or strong, pointing you towards the right mindset for solving their puzzle. Matching these key names with key locations works out immediately, as I figured out with the "shy-shore peeper" swimming around the level perimeter. Likewise, the next stage brought me to a labyrinth of fungi, spider mites, and two confused gnome-y guys who I could choose to reunite. Taking the world in at your own pace, then proceeding through an emotional understanding each environment—it's like learning how to breathe again.

L.O.L finds a sustainable cadence of shorter intro levels, quick interludes, and larger, multi-part affairs, often split up further by your evolution path. Giving three or five psychoballs to the crystal altars sends you on a path of no return, growing larger or more powerful and sometimes losing access to creatures you may or may not have aided. The music-box pupating and subsequent analog spinning to exit your shell always pits a grin on my face. Rather than just being punctuation for a numbers game (ex. Chao raising in Sonic Adventure, much as I love it), every evolution marks a new chapter in the game's broader story, where what you gain or lose with any form mirrors the existential and environmental challenges you've faced. As we transition from the insect world to small mammals and beyond, the heal-or-kill extremes ramp up, as do the level designs. I wouldn't call Love-de-Lic's game particularly mazy or intricate to navigate, but I learned to consult the map for puzzles or sleeping to activate the minimap radar so I could find prey. It'd be easy for this evolve-and-solve formula to get stale or ironically artificial, yet LDL avoids this for nearly the whole runtime!

Early hours of traipsing around a violent but truly honest little universe give way to a mysterious mid-game in which L.O.L. project puppet Halumi intervenes in the great chain of being. An impossibly clean, retro-futurist doll of a destroyer plops down TVs in two levels, each showing a countdown to…something big. Nothing good, that's for sure, and especially not for the unsuspecting locals you've been trying to live with. So far it's mostly just been a couple short tunes and Hirofumi Taniguchi's predictably fascinating sound design for a soundscape, but now the iconic tune "Artificial Paradise" starts droning in the background. Musical ambiance turns to music as a suite, a choreographed piece overriding the vocals and cries you know best. Then the terraformer bots come, and the game introduces another stylistic dalliance: the disaster movie removed from civilization. We've gone from colorful, inviting, mutualistic landscapes to invaded craggy rocksides, a very survival horror-ish insect hive where you play Amida with worker bugs, and a suspiciously utopian "final home" for our alien cat and others just like us.

The final levels satisfyingly wrap all these loose threads into a narrative on the ease with which precarious lives and ecology fall prey to not just the horrors of colonization, but the loss of that mystery needed to keep life worth living. Neither you nor the last creatures you help or save have time or dignity left as the L.O.L. project faces its own consequences, radiating across the world in turn. But I'm familiar with that shared dread and understanding of what it's all coming to, as someone living through destructive climate change my whole lifetime. How does one carry on in a land you remember functioning before it was poisoned? What can family, friends, mutual interests, etc. do against the tide of sheer, uncaring war or collapse?

There's a definite rage hiding behind Love-de-Lic's minimalist approach, only rising to the surface at the game's climax. You can taste the proverbial cookie baked with arsenic, a barbed attitude towards living through these times after growing up hoping and expecting a bright tomorrow. To make it out of this world alive takes a lot of seriousness, but also heart and a sense of humor, which Lack of Love never lets you forget. The ending sequence had me beyond relieved, overjoyed yet mournful about how no environmentalist hero's journey of this sort seems to work beyond the plane of fiction. Is it a lack of love consuming us, or the forced dispersion of it? L.O.L. justifiably refuses to give a clear answer, something even its developers are searching for. It's not the most sophisticated kind of optimistic nihilism anyone's imbued in a work, but a very fitting choice for this adventure.

Plot and thematic spoilers ahead

————————————————————————————

Friendship, whether convenient or desirable on its own, becomes even more important during the second robot attack you suffer through. A mutual species has been living with your newfound family, and one of these more plant-/shroom-shaped fellows is still mourning their dead feline pal near the bottom of the map. Yet again, though, rituals and routines like the egg worship above supplant the ignored pain and due diligence owed in this community. Shoving the guy away from an incoming bulldozer, only to get squashed yourself, is the most you end up doing in this apocalypse. It only gets worse after awakening not in the natural world, but an eerie facsimile of it, built aboard the L.O.L. spaceship that we saw dive into the planet with a virus' silhouette. Even highly-evolved lifeforms, now able to talk in bursts and build a structured society, lose sight and make mistakes. But only humanity can play God for these fauna and flora, such that you're imprisoned in a hell superficially resembling home.