PasokonDeacon

Young Walter Mitty for Japan's jilted generation, a show hazily recalled but always produced. For the residents of Setagaya, it's a St. Vitus dance every end of the week, with too many interpretations to reconcile before the day-to-day grind begins anew. For us, there's a calm before the storm followed by the euphoria of living through a kind disaster, as mild as it is transformative. For the developers, all this presents a release from the simple, sorrowful nostalgia of their past games, a more cynical yet still passionate affair. For Level 5, it's another lauded product in their catalog, a shining example of what Nintendo's 3DS offered to players. For around five hours, this was an bewildering piece of fiction I couldn't get enough of, until somehow I did…and then it couldn't stop. For all of that, I'd feel like a fool to rate this any lower, both for its quality and for how much I esteem the life's work of its creator. Yet this appraisal yearns to be higher.

Consider lead developer Kaz Ayabe, who describes spending a chunk of his post-high school days listening to techno and IDM. Going to rave parties in the countryside, finding his inner caveman…all that energy, melancholy, and plenty of inaka nostalgia fed into what became the Boku no Natsuyasumi series. But where the Bokunatsu games revel in remembered childhood, free from all but the most sensible restrictions, Attack of the Friday Monsters deals directly with a modernity you can't escape, the waking dream of life under smoky layers. Our frame hero, Sohta, is stuck coming of age in a shared stupor, watching and acting through the post-war obsoletion of an imperfect arcadia. And we're brought along for the ride, encapsulated in one interminable day of discovery.

This project was developer Millennium Kitchen's chance to subvert their formula, to leave the proverbial family ramen stall and make a divebar izakaya of a game, both more childish and more adult. It wasn't ever going to be as glamorous or idyllic, but the old recipes and principles which sublimated Bokunatsu into such a masterwork all remain. I just wish Level-5's stipulations and some less well-considered design choices hadn't gotten in the way of this experiment.

Let's settle L5's role in the equation. Their Guild brand of 3DS-exclusive smaller titles—produced/developed together with studios like Nextech, Comcept, Vivarium, and Grasshopper Manufacture—was a smart way to jumpstart the system's paltry launch-window lineup. Why settle for Steel Diver, neat as it is, when cheaper, more immediate larks like Liberation Maiden or Aero Porter are available? Nor did this brand skimp on deeper experiences, like the Yasumi Matsuno-penned Crimson Shroud or the publisher's own Starship Damrey? Among this smorgasbord, Friday Monsters claims its spot as the most relatable, uncompromising adventure within the 3DS' early days. It hardly feels as lacking in meaningful hours of play as you'd expect from a 4-to-6-hour story.

As a Guild02 release, the final product had a similarly low budget and developer count, a budget take on what Ayabe's team and their partners @ Aquria were used to. I can't help but marvel at how they accomplished so much within these limits. While I appreciate L5's former willingness to bankroll and promote other creators' works with little intervention, they clearly signaled their partners to consider how few early adopters the platform had, and how their games should account for that. Finding that balance between "content" and artistic integrity must have been worth the challenge for Ayabe's team, and it leads to an excellent, ambitious yet rougher take on their usual slice-of-life toyboxes.

This makes itself very apparent in the interesting but tedious card collecting & battling system you use throughout Friday Monsters. I knew this was going to get awkward once I noticed the conspicuous lack of tutorializing for anything else in the whole game. Running around, talking to neighbors, and solving simple puzzles all explains itself, but the Monster Glim scavenging and combat rules needed explication. So that's one mark against the game loop's sense of immersion, even if, again, this kind of artifice isn't unusual throughout the experience. I've learned to distinguish the "good" kind of artifice—that which dissuades me from considering the story's events and interactions through realistic terms—and the other, more distracting kind which begs me to question its use or inclusion.

Card battling usually boils down to getting as many gems as you can find, combining cards of a set to increase their power, and then hoping your utterly random placement puts you on the losing end. Rounds come down to who makes the correct rock-paper-scissors predictions, or just has the larger numbers. This all ties into other themes of mutually understood but lightly lampooned adult rules and hierarchies that tie us down, but the player has to go through all this on Sohta's behalf, rather than just existing in plot and dialogue regardless.

Bokunatsu's game loop almost always manages to avoid this pitfall by having you engage in more obvious, more rewarding activities like bug-catching, environmental puzzles, or just managing the passage of time by moving between camera angles. Friday Monsters uses a less chronologically fixed premise, encouraging completion by removing time skips across screens in favor of a loose episodic structure. But even these are more like bookmarks to tracks and remind you of ongoing plot threads, while Ayabe & co. nudge players towards methodically circling the town during each beat. If the typical Bokunatsu day uses its style of progression to force a basic amount of player priority, then what Friday Monsters has instead emphasizes the periphery events and observations of the village's afternoon and evening.

All this comes back to the Guild series' need for back-of-box justification for spending your precious $8, something that Millennium Kitchen's other works aren't so concerned with. What I'm trying to say is that, more than any other Guild release, this one shouldn't have had to include a post-game, or any hinted insecurities about what's "missing". Extra stuff for its own sake is generally optional here, but incentivized by the narrator + promises of extra story which you neither need nor actually get much of in the end.

Much of the story's strengths and staying power comes from what it insinuates, with characters' routines and tribulations shown in enough depth yet elided when necessary to preserve dignity and mystery. After all, it's not just Sohta's tale, the aimless but excited wanderings of a kid trying to take his golden years at a slippery pace. Friday Monsters is just as much concerned with his parents, especially the downtrodden father who wants a courage to live he's never had. While the children only know TV, a story around every corner no matter how slight or recycled, the parents and post-teens stuck on Tokyo's recovering borderlands still remember the tragedies and romance of the cinema or puppet theater.

Sohta's mom and dad are struggling to keep their love and dedication as they enter middle age, denied the economic and cultural promises emblemized in classic Shochiku dramas. Megami and Akebi's dad now have to reconicle their own free time and hobbies with devoting their energy and resources to creating and supporting the tokusatsu shows that seem all too real for Tokyo's new youth, but no different from genre pictures by Toei or Toho. Emiko and her police officer father share an intimate Ozu-esque dialogue while a kaiju duel rages behind them, Setsuko Hara and Chishu Ryu's archetypes juxtaposed against superhero depictions of the country's calamities, environmental injustices, and looming specters of globalization. All of them could fit right onto the silver screen, if they weren't too wrapped up in their comfortable itineraries.

At least he kids are all right. School's always over when they wake up to play, and the simpler joys of learning their vernacular and playing absurd master-servant games never gets old. Two of the boys even reduce their identities to family professions, as Ramen and Billboard both exude their working-class roots in place of stodgy, less memorable formal names. It's precisely that contrast of Sohta & S-chan's mundane but precious growing up with all the frustrations of adulthood which drives not just the plot, but the dive into magical realism this game unleashes upon players.

One example is the protagonist's baffling ability to warp from a seemingly inescapable bad ending back into Ramen's family's diner. Context clues from talking with friends and acquaintances tell the player that Sohta had almost passed out, not remembering his feverish journey to the watering hole, but he doesn't recall nor care that much about it. Any grown-up would understand the gravity of the situation, yet our "hero" plays helpless ghost and witness to an imagination shared with his close circle. Dreams and willpower make any outcome possible on a dog day like this, be it becoming the new cosmic hero of your hometown or falling from Godzilla's claws back into reality. And if they don't even know how to overthink it (discounting A-Plus' genre savvy mumblings), why should we? There's always time later for crack theories about how our protagonist and the "6th cutest girl in class" represent Izanagi and Izanami, after all.

How about the big 'ol kaiju, then? They all look impressive, even if most are reduced to card illustrations. Only Frankasaurus and Cleaner Man get the big 3D showdown, but their wrestling and interactions with Setagaya and the surrounding wards are so damn effective I don't need to see the other giants in action. Nowhere better does Friday Monsters nail its sense of scale and romanticism, that contrast between you and the wider world around you waiting to be explored, than with its climactic fight. Again, it's likely these science fantasy events happening in front of us could be the result of a community's exposure to harmful pollution and chemical from nearby factories, causing hallucinations. But what we're shown could just as well be the real deal, a marvelous if frightening set of circumstances always repeating but rarely understood. This isn't your typical Friday Monsters, uh, Friday twilight—now the unready man of the house becomes an avatar of justice and moral fulfillment, playing Ultraman to Ayabe's hazily remembered Tokyo suburbia. We're not stuck in Sohta's story, nor in his dad's or anyone else's. There's an undercurrent of Japan's indigenous and regional mythology metamorphizing in response to foreign influences, with communal storytelling traditions used here to comment on the transition into the modern.

A great example of Friday Monsters' writing chops is this funny guy named Frank, a well-dressed European gentleman who looks waaaaaaay too much like the original Doctor Who. He's the broadest caricature in this story, an ambassador of weird Western invasion who's nonetheless become part of the community. What part he plays in it, though, remains up to interpretation. Ayaba presents possibilities as wide-ranging as Frank being Sohta's imaginary friend, born from playing with sausages in his bento box. Or he's an elaborate tarento personality working for the local TV station, an example of outside talent brought in from abroad or the local subculture. Maybe this William Hartnell look-a-like really is an alien, the spitting image of an English sophisticate intervening with local affairs for increasingly imperialistic reasons.

No matter what, this one character can go from a cute little sideshow to a narrative-warping anti-hero, stuck between the suspected real and the seductively imagined. That's a lot of adjectives to say this game's full of similarly compelling individuals, each of whom interact with others and the setting in unique ways. Nanafumi, angsty loner and bully in the making, runs the gamut from puzzle obstacle you must solve to a minor hero later in the story, as much a moral example as a person to acknowledge on his own merits. I can remember almost everyone's name here, and not because there's anyone I ever wanted to avoid talking to.

Maybe the story's biggest theme is the theatrical nature of modern life, from Meiji-era home businesses upon farmland to the unavoidable broadcasts and pageantries these families engage in. Friday Monsters indulges you in rituals, from small details like Sohta not wearing his shoes at home to the "ninjutsu" he and the other kids use on each other to show dominance. Pre-rendered 3D environs come to us through carefully chosen camera angles, often disobeying Hollywood's rules of visual progression for the sake of dramatic and thematic effect. Sightlines clue you in on the separation between rural and suburban Tokyo, as well as the pervasive eternal railway walling you off from the picket line and other harsh politics of this era. If anything, I wish there was just a bit more area to explore, or more to interact with on the scenic routes (something Bokunatsu balances well with its lack of urgency). But the game's visual splendor and lush audio design makes it so easy to stay in this world for longer than you'd expect.

Much longer indeed, as I found out when trying the post-game before eventually bouncing off to write this review. There's a simple reason why, as I'd hinted earlier: the "bonus story" of Friday Monsters is antithetical to the game's design and messages. Sure, it'd be nice to learn even more about these people and the weird stories defining them, but we've spent enough time in Sohta's community to know it's worth moving on from. Why crawl around to dig up the scraps when I could just play the core game again? It's like Ayabe & co. are nudging players towards the realization that completionism is a trap both in media and in our own lives, but L5 told them to develop this post-game anyway.

What we're left with is a slower, even more decompressed village to hang out in where Sohta semi-randomly switches conversation topics and more focus goes to card battling or snooping around for the final Monster Glims. This can be fun if played in short bursts, but definitely not as much as the few hours of well-paced, slow and steady social adventuring beforehand. And actually reaching 100% makes this game the kind of slog some of Bokunatsu's skeptics wrongly deem it. Diminishing returns is the last situation I expected here, and it almost sours an otherwise awe-inspiring experience. We even already had a clean opening and ending like you'd see in an anime or children's show from the time, cute theme song and all. Dragging this out threatens to cheapen all the player's just enjoyed.

Encompassing all the intricacies behind this game and its wider context is a battle between idealism and cynicism, with childhood nostalgia as the battleground. I'm unsure if this spinoff's any darker or lighter than the most rigorous Bokunatsu titles, but that almost decade-long gap between this and Millennium Kitchen's recent Shin-chan game stands out to me. After making four summer vacation games with more content, iteration, and repetition than the last, here comes a more constrained, more wanting variation on the genre. (Let's not forget Bokura no Kazoku, a promising inversion of this formula idealizing urban Japan.) Friday Monsters achieves so much immersion and introspection via its clash of ideas against labors, feeling like more than a set of tropes or binaries thrown into its confined space. Perhaps this was Ayabe's own journey to stretch outside the Bokunatsu comfort zone, even knowing he'd have to compromise with his publisher as he'd did with Sony and Contrail years prior. Embracing fantasy to this degree was more than a novelty that would appease Akihiro Hino and other higer-ups; it was the natural next step.

For me, it's just frustrating how close this gets to becoming the masterpiece it hints at. A telltale sign early on was seeing the fairly barebones, clunky UI which makes Bokunatsu's skeuomorphic menus look like fine art. I pressed on and enjoyed myself oh so much anyway, but I can only nod in agreement with Ayabe about the perils of funding these more niche adventures without leaning too far into conventions or market trends. What flaws and missed opportunities crop up here manage to highlight all that Friday Monsters succeeds with, though. Other reviewers have rightly pointed out the sheer charm, verisimilitude, and admirable qualities found all throughout, making it the most complete Guild series entry by some distance. You can't stay in this world forever, no matter how much you want to, but the fond memories of this suburban fantasy can last a lifetime. Here's a story that understands the impossibility of utopia yet lets us yearn for an exciting and sustainable social contract between kids, taller kids, and the processes and solidarity making it all possible.

Nintendo should get raked over the coals for letting media marvels like this fall into unavailability because they can't be bothered to spend chump change on server and network maintenance. Little stories like this are what inspire me to keep playing video games, no matter how much I think I've seen or what I might miss out on. That's most valuable of all.

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Feb. 21 - 27, 2023

Consider lead developer Kaz Ayabe, who describes spending a chunk of his post-high school days listening to techno and IDM. Going to rave parties in the countryside, finding his inner caveman…all that energy, melancholy, and plenty of inaka nostalgia fed into what became the Boku no Natsuyasumi series. But where the Bokunatsu games revel in remembered childhood, free from all but the most sensible restrictions, Attack of the Friday Monsters deals directly with a modernity you can't escape, the waking dream of life under smoky layers. Our frame hero, Sohta, is stuck coming of age in a shared stupor, watching and acting through the post-war obsoletion of an imperfect arcadia. And we're brought along for the ride, encapsulated in one interminable day of discovery.

This project was developer Millennium Kitchen's chance to subvert their formula, to leave the proverbial family ramen stall and make a divebar izakaya of a game, both more childish and more adult. It wasn't ever going to be as glamorous or idyllic, but the old recipes and principles which sublimated Bokunatsu into such a masterwork all remain. I just wish Level-5's stipulations and some less well-considered design choices hadn't gotten in the way of this experiment.

Let's settle L5's role in the equation. Their Guild brand of 3DS-exclusive smaller titles—produced/developed together with studios like Nextech, Comcept, Vivarium, and Grasshopper Manufacture—was a smart way to jumpstart the system's paltry launch-window lineup. Why settle for Steel Diver, neat as it is, when cheaper, more immediate larks like Liberation Maiden or Aero Porter are available? Nor did this brand skimp on deeper experiences, like the Yasumi Matsuno-penned Crimson Shroud or the publisher's own Starship Damrey? Among this smorgasbord, Friday Monsters claims its spot as the most relatable, uncompromising adventure within the 3DS' early days. It hardly feels as lacking in meaningful hours of play as you'd expect from a 4-to-6-hour story.

As a Guild02 release, the final product had a similarly low budget and developer count, a budget take on what Ayabe's team and their partners @ Aquria were used to. I can't help but marvel at how they accomplished so much within these limits. While I appreciate L5's former willingness to bankroll and promote other creators' works with little intervention, they clearly signaled their partners to consider how few early adopters the platform had, and how their games should account for that. Finding that balance between "content" and artistic integrity must have been worth the challenge for Ayabe's team, and it leads to an excellent, ambitious yet rougher take on their usual slice-of-life toyboxes.

This makes itself very apparent in the interesting but tedious card collecting & battling system you use throughout Friday Monsters. I knew this was going to get awkward once I noticed the conspicuous lack of tutorializing for anything else in the whole game. Running around, talking to neighbors, and solving simple puzzles all explains itself, but the Monster Glim scavenging and combat rules needed explication. So that's one mark against the game loop's sense of immersion, even if, again, this kind of artifice isn't unusual throughout the experience. I've learned to distinguish the "good" kind of artifice—that which dissuades me from considering the story's events and interactions through realistic terms—and the other, more distracting kind which begs me to question its use or inclusion.

Card battling usually boils down to getting as many gems as you can find, combining cards of a set to increase their power, and then hoping your utterly random placement puts you on the losing end. Rounds come down to who makes the correct rock-paper-scissors predictions, or just has the larger numbers. This all ties into other themes of mutually understood but lightly lampooned adult rules and hierarchies that tie us down, but the player has to go through all this on Sohta's behalf, rather than just existing in plot and dialogue regardless.

Bokunatsu's game loop almost always manages to avoid this pitfall by having you engage in more obvious, more rewarding activities like bug-catching, environmental puzzles, or just managing the passage of time by moving between camera angles. Friday Monsters uses a less chronologically fixed premise, encouraging completion by removing time skips across screens in favor of a loose episodic structure. But even these are more like bookmarks to tracks and remind you of ongoing plot threads, while Ayabe & co. nudge players towards methodically circling the town during each beat. If the typical Bokunatsu day uses its style of progression to force a basic amount of player priority, then what Friday Monsters has instead emphasizes the periphery events and observations of the village's afternoon and evening.

All this comes back to the Guild series' need for back-of-box justification for spending your precious $8, something that Millennium Kitchen's other works aren't so concerned with. What I'm trying to say is that, more than any other Guild release, this one shouldn't have had to include a post-game, or any hinted insecurities about what's "missing". Extra stuff for its own sake is generally optional here, but incentivized by the narrator + promises of extra story which you neither need nor actually get much of in the end.

Much of the story's strengths and staying power comes from what it insinuates, with characters' routines and tribulations shown in enough depth yet elided when necessary to preserve dignity and mystery. After all, it's not just Sohta's tale, the aimless but excited wanderings of a kid trying to take his golden years at a slippery pace. Friday Monsters is just as much concerned with his parents, especially the downtrodden father who wants a courage to live he's never had. While the children only know TV, a story around every corner no matter how slight or recycled, the parents and post-teens stuck on Tokyo's recovering borderlands still remember the tragedies and romance of the cinema or puppet theater.

Sohta's mom and dad are struggling to keep their love and dedication as they enter middle age, denied the economic and cultural promises emblemized in classic Shochiku dramas. Megami and Akebi's dad now have to reconicle their own free time and hobbies with devoting their energy and resources to creating and supporting the tokusatsu shows that seem all too real for Tokyo's new youth, but no different from genre pictures by Toei or Toho. Emiko and her police officer father share an intimate Ozu-esque dialogue while a kaiju duel rages behind them, Setsuko Hara and Chishu Ryu's archetypes juxtaposed against superhero depictions of the country's calamities, environmental injustices, and looming specters of globalization. All of them could fit right onto the silver screen, if they weren't too wrapped up in their comfortable itineraries.

At least he kids are all right. School's always over when they wake up to play, and the simpler joys of learning their vernacular and playing absurd master-servant games never gets old. Two of the boys even reduce their identities to family professions, as Ramen and Billboard both exude their working-class roots in place of stodgy, less memorable formal names. It's precisely that contrast of Sohta & S-chan's mundane but precious growing up with all the frustrations of adulthood which drives not just the plot, but the dive into magical realism this game unleashes upon players.

One example is the protagonist's baffling ability to warp from a seemingly inescapable bad ending back into Ramen's family's diner. Context clues from talking with friends and acquaintances tell the player that Sohta had almost passed out, not remembering his feverish journey to the watering hole, but he doesn't recall nor care that much about it. Any grown-up would understand the gravity of the situation, yet our "hero" plays helpless ghost and witness to an imagination shared with his close circle. Dreams and willpower make any outcome possible on a dog day like this, be it becoming the new cosmic hero of your hometown or falling from Godzilla's claws back into reality. And if they don't even know how to overthink it (discounting A-Plus' genre savvy mumblings), why should we? There's always time later for crack theories about how our protagonist and the "6th cutest girl in class" represent Izanagi and Izanami, after all.

How about the big 'ol kaiju, then? They all look impressive, even if most are reduced to card illustrations. Only Frankasaurus and Cleaner Man get the big 3D showdown, but their wrestling and interactions with Setagaya and the surrounding wards are so damn effective I don't need to see the other giants in action. Nowhere better does Friday Monsters nail its sense of scale and romanticism, that contrast between you and the wider world around you waiting to be explored, than with its climactic fight. Again, it's likely these science fantasy events happening in front of us could be the result of a community's exposure to harmful pollution and chemical from nearby factories, causing hallucinations. But what we're shown could just as well be the real deal, a marvelous if frightening set of circumstances always repeating but rarely understood. This isn't your typical Friday Monsters, uh, Friday twilight—now the unready man of the house becomes an avatar of justice and moral fulfillment, playing Ultraman to Ayabe's hazily remembered Tokyo suburbia. We're not stuck in Sohta's story, nor in his dad's or anyone else's. There's an undercurrent of Japan's indigenous and regional mythology metamorphizing in response to foreign influences, with communal storytelling traditions used here to comment on the transition into the modern.

A great example of Friday Monsters' writing chops is this funny guy named Frank, a well-dressed European gentleman who looks waaaaaaay too much like the original Doctor Who. He's the broadest caricature in this story, an ambassador of weird Western invasion who's nonetheless become part of the community. What part he plays in it, though, remains up to interpretation. Ayaba presents possibilities as wide-ranging as Frank being Sohta's imaginary friend, born from playing with sausages in his bento box. Or he's an elaborate tarento personality working for the local TV station, an example of outside talent brought in from abroad or the local subculture. Maybe this William Hartnell look-a-like really is an alien, the spitting image of an English sophisticate intervening with local affairs for increasingly imperialistic reasons.

No matter what, this one character can go from a cute little sideshow to a narrative-warping anti-hero, stuck between the suspected real and the seductively imagined. That's a lot of adjectives to say this game's full of similarly compelling individuals, each of whom interact with others and the setting in unique ways. Nanafumi, angsty loner and bully in the making, runs the gamut from puzzle obstacle you must solve to a minor hero later in the story, as much a moral example as a person to acknowledge on his own merits. I can remember almost everyone's name here, and not because there's anyone I ever wanted to avoid talking to.

Maybe the story's biggest theme is the theatrical nature of modern life, from Meiji-era home businesses upon farmland to the unavoidable broadcasts and pageantries these families engage in. Friday Monsters indulges you in rituals, from small details like Sohta not wearing his shoes at home to the "ninjutsu" he and the other kids use on each other to show dominance. Pre-rendered 3D environs come to us through carefully chosen camera angles, often disobeying Hollywood's rules of visual progression for the sake of dramatic and thematic effect. Sightlines clue you in on the separation between rural and suburban Tokyo, as well as the pervasive eternal railway walling you off from the picket line and other harsh politics of this era. If anything, I wish there was just a bit more area to explore, or more to interact with on the scenic routes (something Bokunatsu balances well with its lack of urgency). But the game's visual splendor and lush audio design makes it so easy to stay in this world for longer than you'd expect.

Much longer indeed, as I found out when trying the post-game before eventually bouncing off to write this review. There's a simple reason why, as I'd hinted earlier: the "bonus story" of Friday Monsters is antithetical to the game's design and messages. Sure, it'd be nice to learn even more about these people and the weird stories defining them, but we've spent enough time in Sohta's community to know it's worth moving on from. Why crawl around to dig up the scraps when I could just play the core game again? It's like Ayabe & co. are nudging players towards the realization that completionism is a trap both in media and in our own lives, but L5 told them to develop this post-game anyway.

What we're left with is a slower, even more decompressed village to hang out in where Sohta semi-randomly switches conversation topics and more focus goes to card battling or snooping around for the final Monster Glims. This can be fun if played in short bursts, but definitely not as much as the few hours of well-paced, slow and steady social adventuring beforehand. And actually reaching 100% makes this game the kind of slog some of Bokunatsu's skeptics wrongly deem it. Diminishing returns is the last situation I expected here, and it almost sours an otherwise awe-inspiring experience. We even already had a clean opening and ending like you'd see in an anime or children's show from the time, cute theme song and all. Dragging this out threatens to cheapen all the player's just enjoyed.

Encompassing all the intricacies behind this game and its wider context is a battle between idealism and cynicism, with childhood nostalgia as the battleground. I'm unsure if this spinoff's any darker or lighter than the most rigorous Bokunatsu titles, but that almost decade-long gap between this and Millennium Kitchen's recent Shin-chan game stands out to me. After making four summer vacation games with more content, iteration, and repetition than the last, here comes a more constrained, more wanting variation on the genre. (Let's not forget Bokura no Kazoku, a promising inversion of this formula idealizing urban Japan.) Friday Monsters achieves so much immersion and introspection via its clash of ideas against labors, feeling like more than a set of tropes or binaries thrown into its confined space. Perhaps this was Ayabe's own journey to stretch outside the Bokunatsu comfort zone, even knowing he'd have to compromise with his publisher as he'd did with Sony and Contrail years prior. Embracing fantasy to this degree was more than a novelty that would appease Akihiro Hino and other higer-ups; it was the natural next step.

For me, it's just frustrating how close this gets to becoming the masterpiece it hints at. A telltale sign early on was seeing the fairly barebones, clunky UI which makes Bokunatsu's skeuomorphic menus look like fine art. I pressed on and enjoyed myself oh so much anyway, but I can only nod in agreement with Ayabe about the perils of funding these more niche adventures without leaning too far into conventions or market trends. What flaws and missed opportunities crop up here manage to highlight all that Friday Monsters succeeds with, though. Other reviewers have rightly pointed out the sheer charm, verisimilitude, and admirable qualities found all throughout, making it the most complete Guild series entry by some distance. You can't stay in this world forever, no matter how much you want to, but the fond memories of this suburban fantasy can last a lifetime. Here's a story that understands the impossibility of utopia yet lets us yearn for an exciting and sustainable social contract between kids, taller kids, and the processes and solidarity making it all possible.

Nintendo should get raked over the coals for letting media marvels like this fall into unavailability because they can't be bothered to spend chump change on server and network maintenance. Little stories like this are what inspire me to keep playing video games, no matter how much I think I've seen or what I might miss out on. That's most valuable of all.

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Feb. 21 - 27, 2023

2000

Oh how I love to squid around, showing Ironhead who's the boss of this swim. It's not much larger than a single part of Cave Story, but this little game has an identity beyond just demoing Daisuke "Pixel" Amaya's future works. (Let's also deem this a doujin classic, just like its successor which is so often only called an indie game.) Our unlikely hero has no grim backstory or workmanlike mentality, just the earnestness and intuition to do what's right for this troubled underseas enclave. Jetting around caverns, helping out the residents, and eventually rescuing them from certain doom makes for one exciting hour-long adventure. It's like if Lunar Lander had a story, boss fights, cute characters, and an inimitable style that set Pixel apart from his peers. Squidlander, if you will! Just don't waste your time on the 3DS port, let alone the money Nicalis doesn't deserve.

I'll spare you any more puns and set the scene. The turn of the millennium saw rapid flux in Japan's doujin game community. Widespread adoption of Windows and the Internet meant the old BBS days were fading. Anyone could hop onto Vector.jp, Enterbrain, or another host site to spread their work, get feedback, and maybe get a booth at Comiket or some other big event. All but the most prominent circles were moving on from the PC-98's strict limits in pursuit of new technologies, online multiplayer, and even more niche stories to tell. The conventionality of prior years, a need to design your game for easy transmittal across pricey phone minutes, gave way to the World Wide Web's promises of creative freedom. Only later did programmers, artists, musicians, and designers the world over realize how little had changed. This brief period of Y2K WWW optimism hadn't yet given way to paywalls, community siloing, or the reality distortion fields emanating from social media today. Coteries talked, created, and shared with each other like there was no tomorrow.

Within this primordial soup of an always-online doujin world came Ikachan, hatched out of Pixel's early efforts to make what would become Cave Story. By his own recollection, that better known title started from one of his roommates teaching the future indie legend some game development basics, sometime in 1999. The existence of even earlier micro-games like JiL JiL from 1997 puts this story in question, but it's true that Pixel's earliest software was much smaller in scope and ambition. Pixel's aims of making a multi-hour, consummate experience wouldn't show until this plucky underwater kid graced the Japanese web, using a bespoke engine and music format to massively compress its filesize for distribution. He's mentioned in multiple interviews how keeping these games small, accessible, and ideal for replays has always been the priority, something I think Ikachan exemplifies better than its spiritual successor.

Fittingly, your squid-ling journey begins in an isolated nadir of a small cave system, accompanied only by a smaller starfish fellow trapped behind sponge. This section introduces you to the game's conceit: you can only float and propel left, right, or up, with gravity in effect at all times. Cave Story starts out very similarly, forcing you to learn the base mechanics or face a swift and humiliating demise. I shuddered at the sight of spikes this early on, knowing how fatal they are at the start of the 2004 game, but Pixel's too kind here, letting you survive just one puncture. It's not even a couple minutes or so before you reach the first of many cute urchin friends, each sharing small tidbits about the setting and player goals. And the story tension's made clear right here as you learn about dangerous earthquakes threatening to collapse the whole place. Time's running out to stop the tremors or simply escape, and the player's only just wormed their way out of a craggy prison cell!

Ikachan doesn't deal with time limits, though, nor is it ever what I'd call challenging. Maybe that's because I'm used to the classic gravity platformers that inspired this one, but it's only a matter of patience to navigate these tunnels and bop enemies with your soon acquired mantle. Attacking is never that easy, even once you acquire the jet propulsion ability. Enemies have simple but somewhat jarring movement patterns one must track in order to time floats or boosts, and side attacks simply aren't possible until you get the Capacitor after the first of two bosses. The item & ability progression here is quite satisfying due to said simplicity, at least until after you defeat Ironhead. More than just bopping one or two starfish at a time with easy ways to dodge them, the iconic head honcho requires timing to reliably hit his underside and avoid those charges. Being such a short, restrained design exercise of a project, Ikachan kind of just ends after the big fight, with no new abilities or areas to test your skills. It's a bit of a letdown since the escape sequence could have benefited from even a light 3-to-5 minute timer, just to put more pressure on players.

Pixel compensates for these scant few mini-dungeons and set-pieces with a quality-over-quantity approach. Every critter you meet is memorable, either through appearance or interactions. Neither the PC freeware or 3DS commercial translations feel all that polished like Aeon Genesis' work on Cave Story, but they succeed at conveying the blasé dialogues and economic storytelling you'd expect from this creator. What small areas you dive through, and the mini obstacles you must overcome feel good to surpass. For all I've nitpicked about the game's ending, it's fun to do a kind of victory lap around this netherworld, rescuing each NPC before rocketing off into space, wondering where the hell they're going to end up. And Ikachan has a bit of worldbuilding mystery, too; why were the protagonist and Ben trapped down in the depths to begin with? Were either of them originally from the above world? What kind of bony-finned dumbass would request you deliver them raw blowfish, knowing it'd be poisoned?!

Of course, we can't forget how sumptuous the game looks and sounds even today. This was the debut work featuring Pixel's, uh, highly pixelated and textured artwork, and his catchy PC Engine-like chiptunes in turn. At no point was I ever confused about where to go, a function of a highly readable tileset and use of negative space in these environments. Wise coloring and immediately recognizable character silhouettes gave Ikachan the identity it needed to stand out amidst other, more detailed doujin games of the time. I've always considered this and Cave Story more than just retro throwbacks in both style and substance. They're two of the best examples of minimalist 2D dot visuals I know, and just as impressively coded for efficiency. Performance isn't super smooth due to the 50 FPS limit, but frames never drop and the controls always feel as low-latency as they should. So, despite its rough origins, the game's engine and presentation has more than survived the perils of Windows' evolution.

I wish I could be as glowing and partial to the 3DS version, though, which I acquired through Totally Legal Means and used for a quick replay. Nicalis has a history of making changes and additions to Pixel's work both welcome and dubious. In this case, I'm torn on the level design alterations, which range from adding more rooms to house new enemy types (none of which are much different from the originals) to straight-up padding out runtime. A couple of the routes players take to upgrades are now a bit too long for comfort, but there's a cool change to the Pinky rescue area where you now have to navigate a partially-hidden rock maze. Some nice new details like the shiny claws on crabs help too, yet I can't help but feel all of these changes are either too slight to matter or too irritating to ignore.

Worse still is the new localization, which interferes with the more humble themes and characterization of the original. See, Ikachan was never that much of a hero, nor destined to save the village from destruction. We start from the bottom and then, through our actions and honesty, do the right thing. But the revised character lines point to Nicalis' interpretation of the story, where Pinky becomes a Lisa Simpson type upon and Ironhead's no longer as hostile as he ought to be. The original English translation presents more fitting voices for each NPC and distributes the plot details better across the playthrough. Here it's more haphazardly presented, with Pinky's dad being much more mean to you for no good reason, or the upper tunnels sentry no longer being a pathetic bully like the pearl carrier back below. And there's still no added, meaningful new bits of plot or development here that would justify these liberal rewrites.

The 3DS port is otherwise very faithful, perhaps too much to justify the $5 pricetag. But that's a problem Nicalis faces with Cave Story, too, except they very likely brought ikachan to the eShop as a quick cash grab most of all. No extra sections, bosses, or challenge modes sends a clear sign of "we think you're dumb enough to buy this freeware". Enough's been said about Tyrone Rodriguez's downfall into exploiting Pixel's games and prestige for his benefit, and I hope everyone else who worked on this release got paid properly (or are eventually compensated despite the company president's asshole actions). I still hope this romp gets a proper custom engine or decompilation in the near-future. A level editor exists, and I presume there's gotta be at least one mod out there, but so much oxygen goes to a certain later title that everyone's kind of slept on this one's potential. Well, be the change you want to see in this world, I suppose. This wouldn't be my first time modding a fan favorite game just for my own pleasure.

Until then, Ikachan is a fun, unassuming Metroidvania channeling the better parts of the genre and its legacy. So many doujin and indie works have long since achieved much greater things, yet this would have been my favorite Flash-/Shockwave-ish PC game if I'd stumbled upon it in my childhood. Most importantly, this was something of a missing link between the quaint J-PC doujin period and the increasingly cross-regional, indie-adjacent paradigm that circles and creators now work in. Without this and especially Pixel's next game, so much pomp and circumstance around the revival of the bedroom coder dream may not have worked out as strongly. That's enough reason to try this ditty! It's definitely a case of untapped potential, justifiably viewed as a taste of Pixel's games to come, yet I can boot this up anytime and come away with a smile.

I'll spare you any more puns and set the scene. The turn of the millennium saw rapid flux in Japan's doujin game community. Widespread adoption of Windows and the Internet meant the old BBS days were fading. Anyone could hop onto Vector.jp, Enterbrain, or another host site to spread their work, get feedback, and maybe get a booth at Comiket or some other big event. All but the most prominent circles were moving on from the PC-98's strict limits in pursuit of new technologies, online multiplayer, and even more niche stories to tell. The conventionality of prior years, a need to design your game for easy transmittal across pricey phone minutes, gave way to the World Wide Web's promises of creative freedom. Only later did programmers, artists, musicians, and designers the world over realize how little had changed. This brief period of Y2K WWW optimism hadn't yet given way to paywalls, community siloing, or the reality distortion fields emanating from social media today. Coteries talked, created, and shared with each other like there was no tomorrow.

Within this primordial soup of an always-online doujin world came Ikachan, hatched out of Pixel's early efforts to make what would become Cave Story. By his own recollection, that better known title started from one of his roommates teaching the future indie legend some game development basics, sometime in 1999. The existence of even earlier micro-games like JiL JiL from 1997 puts this story in question, but it's true that Pixel's earliest software was much smaller in scope and ambition. Pixel's aims of making a multi-hour, consummate experience wouldn't show until this plucky underwater kid graced the Japanese web, using a bespoke engine and music format to massively compress its filesize for distribution. He's mentioned in multiple interviews how keeping these games small, accessible, and ideal for replays has always been the priority, something I think Ikachan exemplifies better than its spiritual successor.

Fittingly, your squid-ling journey begins in an isolated nadir of a small cave system, accompanied only by a smaller starfish fellow trapped behind sponge. This section introduces you to the game's conceit: you can only float and propel left, right, or up, with gravity in effect at all times. Cave Story starts out very similarly, forcing you to learn the base mechanics or face a swift and humiliating demise. I shuddered at the sight of spikes this early on, knowing how fatal they are at the start of the 2004 game, but Pixel's too kind here, letting you survive just one puncture. It's not even a couple minutes or so before you reach the first of many cute urchin friends, each sharing small tidbits about the setting and player goals. And the story tension's made clear right here as you learn about dangerous earthquakes threatening to collapse the whole place. Time's running out to stop the tremors or simply escape, and the player's only just wormed their way out of a craggy prison cell!

Ikachan doesn't deal with time limits, though, nor is it ever what I'd call challenging. Maybe that's because I'm used to the classic gravity platformers that inspired this one, but it's only a matter of patience to navigate these tunnels and bop enemies with your soon acquired mantle. Attacking is never that easy, even once you acquire the jet propulsion ability. Enemies have simple but somewhat jarring movement patterns one must track in order to time floats or boosts, and side attacks simply aren't possible until you get the Capacitor after the first of two bosses. The item & ability progression here is quite satisfying due to said simplicity, at least until after you defeat Ironhead. More than just bopping one or two starfish at a time with easy ways to dodge them, the iconic head honcho requires timing to reliably hit his underside and avoid those charges. Being such a short, restrained design exercise of a project, Ikachan kind of just ends after the big fight, with no new abilities or areas to test your skills. It's a bit of a letdown since the escape sequence could have benefited from even a light 3-to-5 minute timer, just to put more pressure on players.

Pixel compensates for these scant few mini-dungeons and set-pieces with a quality-over-quantity approach. Every critter you meet is memorable, either through appearance or interactions. Neither the PC freeware or 3DS commercial translations feel all that polished like Aeon Genesis' work on Cave Story, but they succeed at conveying the blasé dialogues and economic storytelling you'd expect from this creator. What small areas you dive through, and the mini obstacles you must overcome feel good to surpass. For all I've nitpicked about the game's ending, it's fun to do a kind of victory lap around this netherworld, rescuing each NPC before rocketing off into space, wondering where the hell they're going to end up. And Ikachan has a bit of worldbuilding mystery, too; why were the protagonist and Ben trapped down in the depths to begin with? Were either of them originally from the above world? What kind of bony-finned dumbass would request you deliver them raw blowfish, knowing it'd be poisoned?!

Of course, we can't forget how sumptuous the game looks and sounds even today. This was the debut work featuring Pixel's, uh, highly pixelated and textured artwork, and his catchy PC Engine-like chiptunes in turn. At no point was I ever confused about where to go, a function of a highly readable tileset and use of negative space in these environments. Wise coloring and immediately recognizable character silhouettes gave Ikachan the identity it needed to stand out amidst other, more detailed doujin games of the time. I've always considered this and Cave Story more than just retro throwbacks in both style and substance. They're two of the best examples of minimalist 2D dot visuals I know, and just as impressively coded for efficiency. Performance isn't super smooth due to the 50 FPS limit, but frames never drop and the controls always feel as low-latency as they should. So, despite its rough origins, the game's engine and presentation has more than survived the perils of Windows' evolution.

I wish I could be as glowing and partial to the 3DS version, though, which I acquired through Totally Legal Means and used for a quick replay. Nicalis has a history of making changes and additions to Pixel's work both welcome and dubious. In this case, I'm torn on the level design alterations, which range from adding more rooms to house new enemy types (none of which are much different from the originals) to straight-up padding out runtime. A couple of the routes players take to upgrades are now a bit too long for comfort, but there's a cool change to the Pinky rescue area where you now have to navigate a partially-hidden rock maze. Some nice new details like the shiny claws on crabs help too, yet I can't help but feel all of these changes are either too slight to matter or too irritating to ignore.

Worse still is the new localization, which interferes with the more humble themes and characterization of the original. See, Ikachan was never that much of a hero, nor destined to save the village from destruction. We start from the bottom and then, through our actions and honesty, do the right thing. But the revised character lines point to Nicalis' interpretation of the story, where Pinky becomes a Lisa Simpson type upon and Ironhead's no longer as hostile as he ought to be. The original English translation presents more fitting voices for each NPC and distributes the plot details better across the playthrough. Here it's more haphazardly presented, with Pinky's dad being much more mean to you for no good reason, or the upper tunnels sentry no longer being a pathetic bully like the pearl carrier back below. And there's still no added, meaningful new bits of plot or development here that would justify these liberal rewrites.

The 3DS port is otherwise very faithful, perhaps too much to justify the $5 pricetag. But that's a problem Nicalis faces with Cave Story, too, except they very likely brought ikachan to the eShop as a quick cash grab most of all. No extra sections, bosses, or challenge modes sends a clear sign of "we think you're dumb enough to buy this freeware". Enough's been said about Tyrone Rodriguez's downfall into exploiting Pixel's games and prestige for his benefit, and I hope everyone else who worked on this release got paid properly (or are eventually compensated despite the company president's asshole actions). I still hope this romp gets a proper custom engine or decompilation in the near-future. A level editor exists, and I presume there's gotta be at least one mod out there, but so much oxygen goes to a certain later title that everyone's kind of slept on this one's potential. Well, be the change you want to see in this world, I suppose. This wouldn't be my first time modding a fan favorite game just for my own pleasure.

Until then, Ikachan is a fun, unassuming Metroidvania channeling the better parts of the genre and its legacy. So many doujin and indie works have long since achieved much greater things, yet this would have been my favorite Flash-/Shockwave-ish PC game if I'd stumbled upon it in my childhood. Most importantly, this was something of a missing link between the quaint J-PC doujin period and the increasingly cross-regional, indie-adjacent paradigm that circles and creators now work in. Without this and especially Pixel's next game, so much pomp and circumstance around the revival of the bedroom coder dream may not have worked out as strongly. That's enough reason to try this ditty! It's definitely a case of untapped potential, justifiably viewed as a taste of Pixel's games to come, yet I can boot this up anytime and come away with a smile.

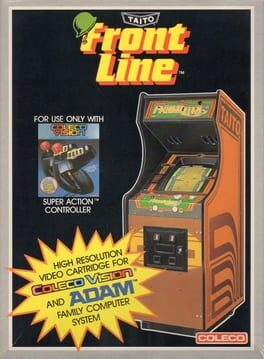

1979

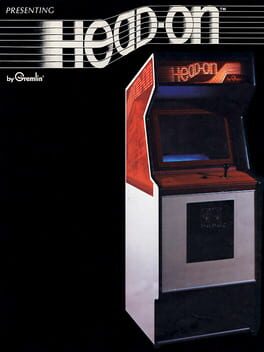

Apply directly to the forehead! Wait, that's a joystick in your hand, not some placebo wax scam. (It's disgraceful how antique software like this never got on my local station's Jeopardy block while that snake oil did.) Now there's a car rolling right towards you in this garish maze, and you're weaving in and out of lanes. This isn't Pac-Man, but it's the beginnings of that formula, with dots to grab and Game Over-s to avoid. Sega-Gremlin had pioneered today's Snake clones with 1976's Blockade; Head On did much the same for maze games before the decade's end.

When this first released in Japan's arcades and adjacent venues, Space Invaders had spent a good half of a year dominating players' attention and wallets. Both games took some time to achieve their breakout sales, but Sega's success with this innovative, US-developed microprocessor board showed the industry that neither Atari's Pong nor Taito's alien shooter were fads. Genre variety was steadily creeping into game centers the world over, and Head On itself was one of the first hybrid titles moving past a ball-and-paddle model. In a sea of sit-down Breakout clones and taikan racers emphasizing the wheel and cabinet, Gremlin's new versus screen-clearing duel of wits must have seemed oddly esoteric.

It's very simple to us today, of course. You drive one car, the AI another, circling a single-screen maze of corridors filled with collectibles. The goal: grab every ball to get that score bonus, all while avoiding a direct collision! But it's easier said than done. Head On's secret sauce is the computer player's tenacity to run you down, driving faster and faster the more pellets you snag. Rather than accelerating in the same lane, you can move up and down to exit and enter the nearest two paths, which works to throw off the AI. The player's only got so much time before the other racer's just too fast to dodge, though, so slam that pedal and finish the course before then!

No extends, a barebones high scoring system, and limited variation across loops means this symmetrical battle of wits gets old fast. There's a bit of strategy to waiting for the AI driver to pass over dots and turn them red, which you can then grab for more points than before. By and large, though, this is as simple as the classic lives-based maze experience gets. I heartily recommend the sequel from that same year, which uses a more complex maze and a second AI racer to keep you invested for much longer. Even so, the original Head On more than earned its popularity. It improved and codified a genre merely toyed with earlier that decade. Gotcha and The Amazing Maze look like prototypes compared to this, something designer Lane Hauck probably knew at the time. Contemporary challengers from later that year, like Taito's Space Chaser or Exidy's Side Trak, each tried new gimmicks to stand out, but the Gremlin originals are frankly more polished and intuitive to play.

While Gremlin never again made such an impact on the Golden Age arcade game milieu, this formed part of Sega's big break into a market then led by Atari, Taito, and Midway. Monaco GP that same year kept up this momentum, as did Head On 2, and many clones spawned in the years to come. Namco 's own Rally-X iterates directly on this premise, though most know a certain pizza-shaped fellow's 1980 maze game better. Gremlin Industries arguably became more important as Sega's vector developer and U.S. board distributor going forward, but none of that would have happened if these early creations never went into production.

Anyone can give this a try nowadays on MAME or the Internet Archive. I'll also mention the various Sega Ages ports via the Memorial Collection discs for Saturn and PS2. This never got a more in-depth remake a la Monaco GP, and that's a shame given Head On's historic significance.

When this first released in Japan's arcades and adjacent venues, Space Invaders had spent a good half of a year dominating players' attention and wallets. Both games took some time to achieve their breakout sales, but Sega's success with this innovative, US-developed microprocessor board showed the industry that neither Atari's Pong nor Taito's alien shooter were fads. Genre variety was steadily creeping into game centers the world over, and Head On itself was one of the first hybrid titles moving past a ball-and-paddle model. In a sea of sit-down Breakout clones and taikan racers emphasizing the wheel and cabinet, Gremlin's new versus screen-clearing duel of wits must have seemed oddly esoteric.

It's very simple to us today, of course. You drive one car, the AI another, circling a single-screen maze of corridors filled with collectibles. The goal: grab every ball to get that score bonus, all while avoiding a direct collision! But it's easier said than done. Head On's secret sauce is the computer player's tenacity to run you down, driving faster and faster the more pellets you snag. Rather than accelerating in the same lane, you can move up and down to exit and enter the nearest two paths, which works to throw off the AI. The player's only got so much time before the other racer's just too fast to dodge, though, so slam that pedal and finish the course before then!

No extends, a barebones high scoring system, and limited variation across loops means this symmetrical battle of wits gets old fast. There's a bit of strategy to waiting for the AI driver to pass over dots and turn them red, which you can then grab for more points than before. By and large, though, this is as simple as the classic lives-based maze experience gets. I heartily recommend the sequel from that same year, which uses a more complex maze and a second AI racer to keep you invested for much longer. Even so, the original Head On more than earned its popularity. It improved and codified a genre merely toyed with earlier that decade. Gotcha and The Amazing Maze look like prototypes compared to this, something designer Lane Hauck probably knew at the time. Contemporary challengers from later that year, like Taito's Space Chaser or Exidy's Side Trak, each tried new gimmicks to stand out, but the Gremlin originals are frankly more polished and intuitive to play.

While Gremlin never again made such an impact on the Golden Age arcade game milieu, this formed part of Sega's big break into a market then led by Atari, Taito, and Midway. Monaco GP that same year kept up this momentum, as did Head On 2, and many clones spawned in the years to come. Namco 's own Rally-X iterates directly on this premise, though most know a certain pizza-shaped fellow's 1980 maze game better. Gremlin Industries arguably became more important as Sega's vector developer and U.S. board distributor going forward, but none of that would have happened if these early creations never went into production.

Anyone can give this a try nowadays on MAME or the Internet Archive. I'll also mention the various Sega Ages ports via the Memorial Collection discs for Saturn and PS2. This never got a more in-depth remake a la Monaco GP, and that's a shame given Head On's historic significance.

1998

Move over 40 Winks Croc: Legend of the Gobbos... Here's the platformer adventure that helped save Apple Computer Inc. from bankruptcy. Every original iMac came bundled with this short but sweet demo, showcasing QuickDraw 3D and giving the kids something fun. And it stars a silly far-future dino blasting through its ancestors to grab some McGuffins. 20 minutes are all you get, and all you need, to have a round with what was possibly the most played GPU-centric game of its day. And it's still worth it today, especially thanks to Iliyas Jorio's source port for modern OSes.

We all love to say 1998 was one of gaming's best years, but rarely does that seem to include the Macintosh. I'm not saying that Apple's once-ailing prosumer home computer line suddenly got anything on the level of Unreal, Metal Gear Solid, or Ocarina of Time, but remember, this was the iMac G3's time to shine. Under interim (and soon permanent) CEO Steve Jobs' direction, the corporation snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, aggressively and effectively marketing a cheap but powerful enough Internet-age Macintosh experience to new users. Tons of schools, businesses, and home users bought into Apple's previously ignored hard and soft ecosystem, even as Windows 95 and its progeny gave Microsoft a near monopoly on the PC space. Beyond a better value product, the iMac was a triumph of design and advertising, this bulbous, umami-like machine benefiting from Mac OS 8's strengths over Windows and previous versions. It also happened to come with a curious pack-in game from this dude out in Austin, TX, stuck in a boring job at Motorola and raring to make another hit shareware game.

Brian Greenstone's the driving force behind Pangea Software and its earlier efforts, mainly Mighty Mike (aka Power Pete) from '95. That earlier release was itself bundled with mid-'90s Performa and Power Macintosh models; Nanosaur logically continued the relationship he'd built with Apple. His early work with Apple's new graphics API, first demoed in '95 and '96, proved important to the iMac's gaming potential, with said line using ATI's baseline Rage II series of accelerator cards. With scarcely more than a month to create a small pack-in title, Greenstone and crew put out what's basically the spiritual successor to Mighty Mike, but set in the Cretaceous.

Nanosaur's premise is simple: you've traveled back in time to 20 minutes before the great meteor mass extinction begins. As part of a civilization of uplifted 'saurs building from humanity's dead remains, you're tasked with collecting five eggs, each from a different species, and returning them to the future. Easier said than done, of course. None of the reptiles are happy to say you invading their land, stealing their young, and blowing up their neighbors. Unluckily for them, our protagonist comes strapped, able to use multiple weapons, power-ups, and a double jump plus jetpack to boot. There's only one level to play over and over again, but it's quite large by '98 standards, and Pangea gives replay incentives like a score table and secret areas.

Actually controlling this raptor is far from smooth going. Croc has the edge on this because it offers strafing, whereas Nanosaur basically uses tank controls. Sense of motion and air control's about as good as in Argonaut Games' platformer, though, and this short thing's more about combat and exploration than pure tests of jumping. No bottomless pits, no required collectibles in the air—none of the frustration I have to grin and bear when trying to save the Gobbos. Turning could have been faster, and I'm pretty sure this control scheme had to account for keyboard-only play, hence the lack of an analog camera. But it's simple, responsive, and offers leeway to less skilled players. Gamepad support's good, too, making it easier to spam shots than just tapping keys. I wish Jorio's port had more options for customizing joy bindings, though.

The game loop itself works very well for something this short. I only wish there was more to actually do here, like a more challenging second level or something. Every cycle of running and jumping across each biome, killing dinos and nabbing eggs to throw into a nearby time portal, feels like a small stage each time. Most enemies just want to ram you for big damage, save the pterodactyls throwing rocks from above. What makes dodging and obliterating them trickier are the environmental hazards, from spore bombs to lava flows, which complicate one's movement and approach. Expect to die a couple times or more when starting out, as there's some traps like the canyon boulders or stegosaurs hiding in shrubs waiting to catch you.

All this comes together to make a thrilling, if very lightweight and predictable fetch-action romp. Granted, it's a miracle Nanosaur plays as well as it does since Greenstone only had three weeks to design and implement the game itself. He'd originally planned this as a QuickDraw 3D demo showing off the tech's potential, as well as his own skin-and-bones animation system inspired by SEGA's recent The Lost World lightgun shooter. To that end, this transformation from pet project to miniaturized Power Pete turned out way better than Greenstone, Apple, or anyone else could have expected. I can beat this in less than 10 minutes, knowing the layout and mechanics quite well now, but so many kids enjoyed trying this over and over again that the runtime hardly matters. There's a quaint joy in optimizing your runs, either for time or score, while jamming out to that funky jungle rock music, traversing the fog for more ammo and health pick-ups to feed your path of destruction.

Pangea had made a relatively small but useful amount of cash over the years, from their Apple IIGS-defining hit Xenocide to the trickle of royalties Greenstone received from MacPlay for Power Pete. But the company's deal with Apple was a boon for everyone, landing him a job on their QuickDraw team and soon leading to more shareware classics for iMac and beyond. As both charityware and a defining pack-in product, Nanosaur marked a maturation of the Mac games market, its success lifting burdens off other beleaguered studios like Bungie and Ambrosia. Greenstone soon leave Apple to give them another hit, the iconic Bugdom a year later, and eventually revisited our plucky chrono-jumping hero with 2004's Nanosaur 2. In the meantime, they put out an expanded paid version of this called Nanosaur Extreme, also included with Jorio's port. All this added was a new high difficulty mode, but having to deal with tens of T-rexes at once definitely gets everything out of the game's design as it deserves. I actually had to stand on geysers and charge up the jetpack when playing this mode, just to keep distance from the hordes cornering me!

I guess the pitch for trying Nanosaur boils down to "cool bipedal boi tears through budget Jurassic Park for great justice". This really isn't something I'd boot up for a revelation or even a great take on the prehistoric action adventure. It's also difficult to appreciate how graphically advanced this was in its time, combining detailed 3D modeling and animation with proto-shaders and a high rendering resolution matching the iMac's hardware. But I'm going out of my way to criticize or downplay a humble, very enjoyable piece of history which stacks up well to modern game jam faire. It takes the best parts of Mighty Mike and competing efforts like Ambrosia's Harry the Handsome Executive, shunting the Mac shareware world into polygonal view just like Avara and Marathon 2 had tried. Weird freeware collect-a-thon platformers would never be the same; given how far this one spread, they could only strive to beat this benchmark.

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Mar. 7 - 13, 2023

We all love to say 1998 was one of gaming's best years, but rarely does that seem to include the Macintosh. I'm not saying that Apple's once-ailing prosumer home computer line suddenly got anything on the level of Unreal, Metal Gear Solid, or Ocarina of Time, but remember, this was the iMac G3's time to shine. Under interim (and soon permanent) CEO Steve Jobs' direction, the corporation snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, aggressively and effectively marketing a cheap but powerful enough Internet-age Macintosh experience to new users. Tons of schools, businesses, and home users bought into Apple's previously ignored hard and soft ecosystem, even as Windows 95 and its progeny gave Microsoft a near monopoly on the PC space. Beyond a better value product, the iMac was a triumph of design and advertising, this bulbous, umami-like machine benefiting from Mac OS 8's strengths over Windows and previous versions. It also happened to come with a curious pack-in game from this dude out in Austin, TX, stuck in a boring job at Motorola and raring to make another hit shareware game.

Brian Greenstone's the driving force behind Pangea Software and its earlier efforts, mainly Mighty Mike (aka Power Pete) from '95. That earlier release was itself bundled with mid-'90s Performa and Power Macintosh models; Nanosaur logically continued the relationship he'd built with Apple. His early work with Apple's new graphics API, first demoed in '95 and '96, proved important to the iMac's gaming potential, with said line using ATI's baseline Rage II series of accelerator cards. With scarcely more than a month to create a small pack-in title, Greenstone and crew put out what's basically the spiritual successor to Mighty Mike, but set in the Cretaceous.

Nanosaur's premise is simple: you've traveled back in time to 20 minutes before the great meteor mass extinction begins. As part of a civilization of uplifted 'saurs building from humanity's dead remains, you're tasked with collecting five eggs, each from a different species, and returning them to the future. Easier said than done, of course. None of the reptiles are happy to say you invading their land, stealing their young, and blowing up their neighbors. Unluckily for them, our protagonist comes strapped, able to use multiple weapons, power-ups, and a double jump plus jetpack to boot. There's only one level to play over and over again, but it's quite large by '98 standards, and Pangea gives replay incentives like a score table and secret areas.

Actually controlling this raptor is far from smooth going. Croc has the edge on this because it offers strafing, whereas Nanosaur basically uses tank controls. Sense of motion and air control's about as good as in Argonaut Games' platformer, though, and this short thing's more about combat and exploration than pure tests of jumping. No bottomless pits, no required collectibles in the air—none of the frustration I have to grin and bear when trying to save the Gobbos. Turning could have been faster, and I'm pretty sure this control scheme had to account for keyboard-only play, hence the lack of an analog camera. But it's simple, responsive, and offers leeway to less skilled players. Gamepad support's good, too, making it easier to spam shots than just tapping keys. I wish Jorio's port had more options for customizing joy bindings, though.

The game loop itself works very well for something this short. I only wish there was more to actually do here, like a more challenging second level or something. Every cycle of running and jumping across each biome, killing dinos and nabbing eggs to throw into a nearby time portal, feels like a small stage each time. Most enemies just want to ram you for big damage, save the pterodactyls throwing rocks from above. What makes dodging and obliterating them trickier are the environmental hazards, from spore bombs to lava flows, which complicate one's movement and approach. Expect to die a couple times or more when starting out, as there's some traps like the canyon boulders or stegosaurs hiding in shrubs waiting to catch you.

All this comes together to make a thrilling, if very lightweight and predictable fetch-action romp. Granted, it's a miracle Nanosaur plays as well as it does since Greenstone only had three weeks to design and implement the game itself. He'd originally planned this as a QuickDraw 3D demo showing off the tech's potential, as well as his own skin-and-bones animation system inspired by SEGA's recent The Lost World lightgun shooter. To that end, this transformation from pet project to miniaturized Power Pete turned out way better than Greenstone, Apple, or anyone else could have expected. I can beat this in less than 10 minutes, knowing the layout and mechanics quite well now, but so many kids enjoyed trying this over and over again that the runtime hardly matters. There's a quaint joy in optimizing your runs, either for time or score, while jamming out to that funky jungle rock music, traversing the fog for more ammo and health pick-ups to feed your path of destruction.

Pangea had made a relatively small but useful amount of cash over the years, from their Apple IIGS-defining hit Xenocide to the trickle of royalties Greenstone received from MacPlay for Power Pete. But the company's deal with Apple was a boon for everyone, landing him a job on their QuickDraw team and soon leading to more shareware classics for iMac and beyond. As both charityware and a defining pack-in product, Nanosaur marked a maturation of the Mac games market, its success lifting burdens off other beleaguered studios like Bungie and Ambrosia. Greenstone soon leave Apple to give them another hit, the iconic Bugdom a year later, and eventually revisited our plucky chrono-jumping hero with 2004's Nanosaur 2. In the meantime, they put out an expanded paid version of this called Nanosaur Extreme, also included with Jorio's port. All this added was a new high difficulty mode, but having to deal with tens of T-rexes at once definitely gets everything out of the game's design as it deserves. I actually had to stand on geysers and charge up the jetpack when playing this mode, just to keep distance from the hordes cornering me!

I guess the pitch for trying Nanosaur boils down to "cool bipedal boi tears through budget Jurassic Park for great justice". This really isn't something I'd boot up for a revelation or even a great take on the prehistoric action adventure. It's also difficult to appreciate how graphically advanced this was in its time, combining detailed 3D modeling and animation with proto-shaders and a high rendering resolution matching the iMac's hardware. But I'm going out of my way to criticize or downplay a humble, very enjoyable piece of history which stacks up well to modern game jam faire. It takes the best parts of Mighty Mike and competing efforts like Ambrosia's Harry the Handsome Executive, shunting the Mac shareware world into polygonal view just like Avara and Marathon 2 had tried. Weird freeware collect-a-thon platformers would never be the same; given how far this one spread, they could only strive to beat this benchmark.

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Mar. 7 - 13, 2023

1982

Making cartridge games in the pre-Famicom years posed a dilemma: they couldn't store much game without costing customers and manufacturers out the butt. It's no surprise that Nintendo later made their own disk add-on, among others, in order to distribute cheaper, larger software. All the excess cart inventory that flooded North American console markets, thus precipitating the region's early-'80s crash, finally got discounted to rates we'd expect today. And it's in that period of decline where something like Miner 2049er would have appealed to Atari PC owners normally priced out of cart games.

This 16K double-board release promised 10 levels of arcade-y, highly replayable platform adventuring, among other items of praise littering the pages of newsletters and magazines. Just one problem: it's a poor mash-up of Donkey Kong, Pac-Man, and other better cabinet faire you'd lose less quarters from and enjoy more. This was the same year one could find awesome, innovative experiences like Moon Patrol down at the bar or civic center, let alone Activision's Pitfall and other tech-pushing Atari VCS works. Hell, I'd rather deal with all the exhausting RNG-laden dungeons of Castle Wolfenstein right now than bother with a jack of all trades + master of none such as this.

I don't mean to bag on Bill Hogue's 1982 work that much, knowing the trials and tribulations of bedroom coding in those days. He'd made a modest living off many TRS-80 clones of arcade staples, only having to make this once Radio Shack/Tandy discontinued that platform. His studio Big Five debuted on Apple II & Atari 800 with this unwieldy thing, so large they couldn't smush it into the standard cartridge size of the latter machine. Contrast this with David Crane's masterful compression of Pitfall into just 4 kiloybytes, a quarter as big yet much more enjoyable a play. Surely all these unique stages in Miner 2049er would have given it the edge on other primordial platformers, right? That's what I hoped for going in, not that I expected anything amazing. To my disappointment, its mechanics, progression, and overall game-feel just seems diluted to the point of disrespecting its inspirations.