Detchibe

BACKER

Sweet as sugar.

Sweet as young love.

Sweet as can be.

Nostalgic and enraptured with youth as Norwegian Wood.

Magical and intertwined as Kafka on the Shore.

Two blurred lines proceeding apace in parallel as 1Q84.

Perfectly self contained within its own narrative.

Abound with the peculiarities of children.

Spare and sparse.

Father's guidance.

Mother's embrace.

One's own destiny.

Comfortable.

Joyful.

Warm.

Sweet as young love.

Sweet as can be.

Nostalgic and enraptured with youth as Norwegian Wood.

Magical and intertwined as Kafka on the Shore.

Two blurred lines proceeding apace in parallel as 1Q84.

Perfectly self contained within its own narrative.

Abound with the peculiarities of children.

Spare and sparse.

Father's guidance.

Mother's embrace.

One's own destiny.

Comfortable.

Joyful.

Warm.

2022

A layered cocktail that needs some shaking and stirring of its components.

The process of learning a new roguelite is one that, with enough experience, boils down to determining what works with what. This goes doubly for an engine-builder where the composition of the engine is just as important as its execution. Your Isaacs and Gungeons can be finished with poor items and pure skill, but when constructing a deck the parts need to work in harmony.

Peglin wants to have it both ways with its appropriation of Peggle's adaptation of pachinko machines. Whereas Peggle largely removed the element of luck in all but name (the Zen Ball making it most apparent that this is a game of skill), Peglin has done away with the possibility of winning with skill. Everything is down to RNG in one way or another, and the worst part is that Peglin refuses to admit this to the player. In this sense, Peglin is no different from its pachinko machine grandfather, the specific tuning of the latter's pins betraying the simple proposition of getting a ball to its goal.

The crux of the issue is that the player has no way of changing their odds in a meaningful way. Like other engine-builders, you are presented a few random choices for what passive items or balls you want to take. After battle you can upgrade your orbs if you wish. While other engine-builder roguelites like Slay the Spire and Monster Train offer the choice of card for free, Peglin assigns a cost to this and grants shockingly few opportunities to remove balls from the deck. Each shop does let you remove one ball for a fee, but you're going to have to bounce your way over there and thus structure your play in service of those spare few chances.

Building an engine is itself troublesome due to the nature of play. For starters, balls can have their own gravity which is further affected by bouncy pegs, bombs, gravity wells, slime bubbles, and other hazards. On top of this, the ball does not necessarily go to where the pointer is -- Peggle's balls always went straight to the pointer. Coupled with a paltry shot preview, each shot is a skewed gamble, a vague gesture of intent that is rarely realised. The game's confusion status which rapidly rotates your aim might as well be on by default, the end result is nearly identical. Even ignoring the inefficacy of aiming, without a way to meaningfully affect your luck, you can end up with a build that shoots itself in the foot. Whether due to my own (un)luck of the game's internal weighting, nearly every run of mine has been focused on increasing non-critical damage to ludicrous levels. That feels fun, but it is made instantly worthless if my ball hits a crit modifier, my damage cut down tenfold if not more. With a proper ability to aim my shots that would be fine, I would simply aim away from my Achilles' heel, but a refreshing of the board, an errant moving peg, a black hole, any number of possibilities will ensure my ball is heading straight for the one thing I don't want to have happen. That does not feel like I played poorly, it feels like the rug was pulled out from under me.

Most damning of all is that Peglin lacks the aesthetic, dopaminergic je ne sais quoi that makes Peggle so ultra-satisfying. Hitting a peg is a flaccid act without whimsy, the visual feedback a nothingburger of a number, the audio presented as effective white noise. The labouriously slow traversal of the ball makes each shot a tedium, something the developers are clearly aware of as there is a prevalent fast forward button which can knock the speed up to 300%. I am never on the edge of my seat, gnawing my nails hoping my shot was planned correctly, that I will hit that last peg with my final shot, the world holding its breath. I never feel my aptitude increasing. I only feel my time is being wasted, just as Peglin's potential is.

The process of learning a new roguelite is one that, with enough experience, boils down to determining what works with what. This goes doubly for an engine-builder where the composition of the engine is just as important as its execution. Your Isaacs and Gungeons can be finished with poor items and pure skill, but when constructing a deck the parts need to work in harmony.

Peglin wants to have it both ways with its appropriation of Peggle's adaptation of pachinko machines. Whereas Peggle largely removed the element of luck in all but name (the Zen Ball making it most apparent that this is a game of skill), Peglin has done away with the possibility of winning with skill. Everything is down to RNG in one way or another, and the worst part is that Peglin refuses to admit this to the player. In this sense, Peglin is no different from its pachinko machine grandfather, the specific tuning of the latter's pins betraying the simple proposition of getting a ball to its goal.

The crux of the issue is that the player has no way of changing their odds in a meaningful way. Like other engine-builders, you are presented a few random choices for what passive items or balls you want to take. After battle you can upgrade your orbs if you wish. While other engine-builder roguelites like Slay the Spire and Monster Train offer the choice of card for free, Peglin assigns a cost to this and grants shockingly few opportunities to remove balls from the deck. Each shop does let you remove one ball for a fee, but you're going to have to bounce your way over there and thus structure your play in service of those spare few chances.

Building an engine is itself troublesome due to the nature of play. For starters, balls can have their own gravity which is further affected by bouncy pegs, bombs, gravity wells, slime bubbles, and other hazards. On top of this, the ball does not necessarily go to where the pointer is -- Peggle's balls always went straight to the pointer. Coupled with a paltry shot preview, each shot is a skewed gamble, a vague gesture of intent that is rarely realised. The game's confusion status which rapidly rotates your aim might as well be on by default, the end result is nearly identical. Even ignoring the inefficacy of aiming, without a way to meaningfully affect your luck, you can end up with a build that shoots itself in the foot. Whether due to my own (un)luck of the game's internal weighting, nearly every run of mine has been focused on increasing non-critical damage to ludicrous levels. That feels fun, but it is made instantly worthless if my ball hits a crit modifier, my damage cut down tenfold if not more. With a proper ability to aim my shots that would be fine, I would simply aim away from my Achilles' heel, but a refreshing of the board, an errant moving peg, a black hole, any number of possibilities will ensure my ball is heading straight for the one thing I don't want to have happen. That does not feel like I played poorly, it feels like the rug was pulled out from under me.

Most damning of all is that Peglin lacks the aesthetic, dopaminergic je ne sais quoi that makes Peggle so ultra-satisfying. Hitting a peg is a flaccid act without whimsy, the visual feedback a nothingburger of a number, the audio presented as effective white noise. The labouriously slow traversal of the ball makes each shot a tedium, something the developers are clearly aware of as there is a prevalent fast forward button which can knock the speed up to 300%. I am never on the edge of my seat, gnawing my nails hoping my shot was planned correctly, that I will hit that last peg with my final shot, the world holding its breath. I never feel my aptitude increasing. I only feel my time is being wasted, just as Peglin's potential is.

2000

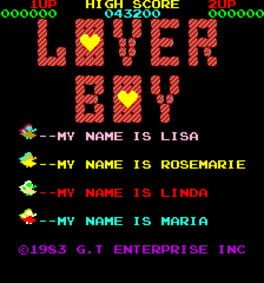

1983

This review is a sister piece to my review of 177. I recommend reading that first.

CW: Sexual assault. The four-letter ‘R-word’ is invoked repeatedly without censoring or obfuscation.

WHEN YOU CATCH A GIRL YOU MUST FIND RIGHT TIMING FOR MAXIMUM RESULT WHICH WILL BE SHOWN ON LOVE METER ACTION OF LOVE MAKING IS BY PUSH BUTTON. BEST TIMING WILL PRODUCE MOST ECSTATIC RESULTS ON FEMALE METER.

Lover Boy is functionally unremarkable, seemingly of as much import as Min Corp.’s Gumbo or Toaplan’s Pipi & Bibi’s. Unlike those games, however, Lover Boy is mired in obscurity, controversy, and a historiography that crumbles under scrutiny.

The gameplay is in line with other maze games of the early 1980s. The Lover Boy chases Lisa, Rosemarie, Linda, and Maria through a labyrinth while police officers and dogs track him. There are item pickups for points, and bottles of perfume which incense Lover Boy, boosting his speed dramatically. All the while, a rendition of the nursery rhyme しょうじょうじのたぬきばやし 「 Shoujouji no Tanukibayashi」 plays merrily. Getting near the girls causes them to run away while yelling HELP, touching them starts your digital assault. Like 177, the player tries to get their victim’s pleasure meter to top out before Lover Boy climaxes. Though 177 used directional inputs, Lover Boy simply has you tapping the button at a steady rhythm. Filling the LADY LOVE to the heart at the top has the women elate Oh~. Climaxing before she can has her yelling NO! and escaping, Lover Boy needing to chase her down again.

Though less explicitly stated in Lover Boy as compared to 177, we see the same rape myth being perpetuated, that of rape becoming a consensual sexual act should the victim reach orgasm. Since Lover Boy is an arcade game, designed to munch the yen of the aroused, there is no good ending to speak of here. The cycle continues in perpetuity until Lover Boy is put behind bars for good. This might suggest an inevitability to the rapist being caught and punished accordingly in due time, but the lives system inadvertently paints a picture wherein a sexual criminal is released and allowed to repeat their crimes with minimal repercussion. Lest we forget the harrowing injustice presented in 177’s manual, “even if he was prosecuted then, he would not be charged with a crime.” Capture is thus an inconvenience, nothing more.

In trying to find out more about Lover Boy, I came to find out it was cause for debate in the Deutscher Bundestag a year after its release. On March 26, 1984, parliamentary spokespersons for Die Grünen (The Greens) Marieluise Beck, Petra Kelly, and Otto Schily brought to the attention of the federal government the installation of light-gun games and Lover Boy in an arcade in Soest. Both were cited as potential violations of Section 131 of the Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code), stating therein the illegality of representations which glorified violence. Increasingly realistic depictions of humans as targets for violence, both physical and sexual, necessitated a re-evaluation of existing legislation which made no such effort to criminalise imagery which ‘violated human dignity.’

Sixteen days later, the Federal Government answered the concerns of Die Grünen. The government had come to understand Lover Boy was installed in locations besides Soest, with the understanding that the PCB had been presented by an Italian importer in 1983 at Internationalen Fachmesse für Unterhaltungs- und Warenautomaten (The International Trade Fair for Amusement and Vending Machines) in Frankfurt. The specific board in Soest which drew initial concerns was sourced from a distributor in Dortmund. A March 1984 arcade game trade journal advertised Lover Boy as suitable for children, and thirty-two machines ended up being sold in North Rhine-Westphalia alone, and it came to be understood that Automaten-Selbstkontrolle (ASK) had been presented with incomplete information by which to rate its content; the content was egregious enough to exclude Lover Boy from any rating, leading to the existing machines being purchased and destroyed. A draft law was proposed to the Bundestag, stipulating that games of a violent sort must be prohibited from public areas frequented by children, and postulating that perhaps violent games should be banned wholesale in Germany.

A year later, in April 1985, Section 131 of the Strafgeseztbuch was amended to prohibit representations of violence, rather than just those which glorified it. Additionally, depictions of the ‘violation of human dignity’ were criminalised as well. The ASK became a permanent institution, officially regulating an industry that had, up to that point, been self-regulated.

The ban in Germany is easy to trace, but time and again, it is stated in other reviews and retrospectives that Lover Boy was banned globally outside of Japan with zero evidence offered to support that claim. Searches for “Lover Boy” and “Global Corporation Tokyo” in the United States Congressional Record, Historical Debates of the Parliament of Canada, British Cabinet Papers, CommonLii, Italian Senate record, New York Times, Globe & Mail, all turned up nothing. The German Wikipedia page also makes no mention of Lover Boy being banned anywhere outside of Germany.

Outside of the Bundestag record, some of the only other concrete information about Lover Boy is that it was brought to market by the same company that made 1983’s JoinEm, a non-erotic maze game, released under the name Global Corporation. The pinout and DIP switch documentation included with the Lover Boy PCB had Lover Boy handwritten on them. Weirding the situation further, a seeming bootleg of Lover Boy was released in Spain under the name Triki Triki, changing the developer name to DDT Enterprise, editing the copyright date to 1993.-nicht-jugendfrei-und-nicht-in-Mame/page10) The trail ends there.

If I were to posit a guess, the majority of the inaccurate claims about Lover Boy stem from a single GameFAQs review by defunct user ‘TheSAMMIES’. They claim, erroneously, that Lover Boy:

- Deals with aspects of rape beyond the penetrative act

- Has been banned globally

- Has better gameplay than 177

- Is slang for a man who lures underage women into prostitution (the term is only used in that manner in Dutch)

- Depicts only underage women

- Displays female genitalia

- Has only one maze

- Is of dark comedic value

None of that is true whatsoever. Their spurious falsehoods are on display in their review of 177 as well, claiming falsely:

- 177 is the police code for rape (it is simply the section of the Japanese Criminal Code which criminalises rape)

- RapeLay tackles rape more tactfully

- 177’s rape scenes show plant life and the night sky (they actually occur in a black void)

- Has controls in its rape scenes for getting onto Kotoe, penetrating her, building up sexual stamina (you actually just gyrate, the graphics barely animating)

- That 177 received a remake called 171 wherein Hideo is replaced by a squid monster, Kotoe by a maid (I have found no evidence of such a game existing)

Whether these ideas are being born purely from their mind, some misinterpretation of the realities of history, or whatever else, this individual seems to have irreparably tarnished the known history of Lover Boy, leading to prolonged repetition of the same incorrect claims. If there were any evidence to back up those ideas, wouldn’t they have shown themselves? Does it matter? Nobody cares about this game, nobody knows about it, can we fault the few who have documented it for their inaccuracies?

Yes, because it makes determining the truth all the harder. Yes, because it puts the onus of honestly on those who come after the fact. Yes, because just as these games are harmful in their depictions, speaking of them falsely is just as much of a disservice to history.

CW: Sexual assault. The four-letter ‘R-word’ is invoked repeatedly without censoring or obfuscation.

WHEN YOU CATCH A GIRL YOU MUST FIND RIGHT TIMING FOR MAXIMUM RESULT WHICH WILL BE SHOWN ON LOVE METER ACTION OF LOVE MAKING IS BY PUSH BUTTON. BEST TIMING WILL PRODUCE MOST ECSTATIC RESULTS ON FEMALE METER.

Lover Boy is functionally unremarkable, seemingly of as much import as Min Corp.’s Gumbo or Toaplan’s Pipi & Bibi’s. Unlike those games, however, Lover Boy is mired in obscurity, controversy, and a historiography that crumbles under scrutiny.

The gameplay is in line with other maze games of the early 1980s. The Lover Boy chases Lisa, Rosemarie, Linda, and Maria through a labyrinth while police officers and dogs track him. There are item pickups for points, and bottles of perfume which incense Lover Boy, boosting his speed dramatically. All the while, a rendition of the nursery rhyme しょうじょうじのたぬきばやし 「 Shoujouji no Tanukibayashi」 plays merrily. Getting near the girls causes them to run away while yelling HELP, touching them starts your digital assault. Like 177, the player tries to get their victim’s pleasure meter to top out before Lover Boy climaxes. Though 177 used directional inputs, Lover Boy simply has you tapping the button at a steady rhythm. Filling the LADY LOVE to the heart at the top has the women elate Oh~. Climaxing before she can has her yelling NO! and escaping, Lover Boy needing to chase her down again.

Though less explicitly stated in Lover Boy as compared to 177, we see the same rape myth being perpetuated, that of rape becoming a consensual sexual act should the victim reach orgasm. Since Lover Boy is an arcade game, designed to munch the yen of the aroused, there is no good ending to speak of here. The cycle continues in perpetuity until Lover Boy is put behind bars for good. This might suggest an inevitability to the rapist being caught and punished accordingly in due time, but the lives system inadvertently paints a picture wherein a sexual criminal is released and allowed to repeat their crimes with minimal repercussion. Lest we forget the harrowing injustice presented in 177’s manual, “even if he was prosecuted then, he would not be charged with a crime.” Capture is thus an inconvenience, nothing more.

In trying to find out more about Lover Boy, I came to find out it was cause for debate in the Deutscher Bundestag a year after its release. On March 26, 1984, parliamentary spokespersons for Die Grünen (The Greens) Marieluise Beck, Petra Kelly, and Otto Schily brought to the attention of the federal government the installation of light-gun games and Lover Boy in an arcade in Soest. Both were cited as potential violations of Section 131 of the Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code), stating therein the illegality of representations which glorified violence. Increasingly realistic depictions of humans as targets for violence, both physical and sexual, necessitated a re-evaluation of existing legislation which made no such effort to criminalise imagery which ‘violated human dignity.’

Sixteen days later, the Federal Government answered the concerns of Die Grünen. The government had come to understand Lover Boy was installed in locations besides Soest, with the understanding that the PCB had been presented by an Italian importer in 1983 at Internationalen Fachmesse für Unterhaltungs- und Warenautomaten (The International Trade Fair for Amusement and Vending Machines) in Frankfurt. The specific board in Soest which drew initial concerns was sourced from a distributor in Dortmund. A March 1984 arcade game trade journal advertised Lover Boy as suitable for children, and thirty-two machines ended up being sold in North Rhine-Westphalia alone, and it came to be understood that Automaten-Selbstkontrolle (ASK) had been presented with incomplete information by which to rate its content; the content was egregious enough to exclude Lover Boy from any rating, leading to the existing machines being purchased and destroyed. A draft law was proposed to the Bundestag, stipulating that games of a violent sort must be prohibited from public areas frequented by children, and postulating that perhaps violent games should be banned wholesale in Germany.

A year later, in April 1985, Section 131 of the Strafgeseztbuch was amended to prohibit representations of violence, rather than just those which glorified it. Additionally, depictions of the ‘violation of human dignity’ were criminalised as well. The ASK became a permanent institution, officially regulating an industry that had, up to that point, been self-regulated.

The ban in Germany is easy to trace, but time and again, it is stated in other reviews and retrospectives that Lover Boy was banned globally outside of Japan with zero evidence offered to support that claim. Searches for “Lover Boy” and “Global Corporation Tokyo” in the United States Congressional Record, Historical Debates of the Parliament of Canada, British Cabinet Papers, CommonLii, Italian Senate record, New York Times, Globe & Mail, all turned up nothing. The German Wikipedia page also makes no mention of Lover Boy being banned anywhere outside of Germany.

Outside of the Bundestag record, some of the only other concrete information about Lover Boy is that it was brought to market by the same company that made 1983’s JoinEm, a non-erotic maze game, released under the name Global Corporation. The pinout and DIP switch documentation included with the Lover Boy PCB had Lover Boy handwritten on them. Weirding the situation further, a seeming bootleg of Lover Boy was released in Spain under the name Triki Triki, changing the developer name to DDT Enterprise, editing the copyright date to 1993.-nicht-jugendfrei-und-nicht-in-Mame/page10) The trail ends there.

If I were to posit a guess, the majority of the inaccurate claims about Lover Boy stem from a single GameFAQs review by defunct user ‘TheSAMMIES’. They claim, erroneously, that Lover Boy:

- Deals with aspects of rape beyond the penetrative act

- Has been banned globally

- Has better gameplay than 177

- Is slang for a man who lures underage women into prostitution (the term is only used in that manner in Dutch)

- Depicts only underage women

- Displays female genitalia

- Has only one maze

- Is of dark comedic value

None of that is true whatsoever. Their spurious falsehoods are on display in their review of 177 as well, claiming falsely:

- 177 is the police code for rape (it is simply the section of the Japanese Criminal Code which criminalises rape)

- RapeLay tackles rape more tactfully

- 177’s rape scenes show plant life and the night sky (they actually occur in a black void)

- Has controls in its rape scenes for getting onto Kotoe, penetrating her, building up sexual stamina (you actually just gyrate, the graphics barely animating)

- That 177 received a remake called 171 wherein Hideo is replaced by a squid monster, Kotoe by a maid (I have found no evidence of such a game existing)

Whether these ideas are being born purely from their mind, some misinterpretation of the realities of history, or whatever else, this individual seems to have irreparably tarnished the known history of Lover Boy, leading to prolonged repetition of the same incorrect claims. If there were any evidence to back up those ideas, wouldn’t they have shown themselves? Does it matter? Nobody cares about this game, nobody knows about it, can we fault the few who have documented it for their inaccuracies?

Yes, because it makes determining the truth all the harder. Yes, because it puts the onus of honestly on those who come after the fact. Yes, because just as these games are harmful in their depictions, speaking of them falsely is just as much of a disservice to history.

Weird: Automaton

The only instance in Keita Takahashi's oeuvre of overt difficulty and challenge. Whereas stages in Katamari Damacy and We Love Katamari occasionally presented the player with moments that tested their skill and know-how -- primarily in the former's Ursa Major and Taurus levels, the latter's Cowbear request -- Crankin Presents Time Travel Adventure offers little of the toy-like reprieve found in Takahashi's other titles. This has no doubt caught most Playdate owners off-guard, particularly those who, like me, picked up a Playdate almost exclusively for a new digital Takahashi playground. What we received instead is a (literally) mechanically intense movement-based, animation-frame-dependent dodge-em-up featuring memorisation and routing like one would expect from Gradius, with the pixel perfect precision of I Want To Be The Guy in a coat of Wattam paint.

Here more than with any other Playdate title, the specifics of the crank must be appreciated. Like an electromechanical re-imagining of a well-oiled wooden crank toy, the rotation is smooth and defined with just enough resistance to keep it steady when not being turned. This is critical in Crankin Presents as it means each position of the crank at a point in time correlates exactly with a state in Crankin's timeline. Rotating the crank, say, exactly 476.2 degrees, then cranking it the other way 476.2 degrees back puts me in the exact same frame of animation, the same location I was in. This results in two layers of memorisation being demanded of the player.

On a macro level, many date's layouts must be roughly mentally mapped out to understand where hazards are, and where they can be avoided. On the micro level, each attempt's variations in where your cranking starts and ends, and the need for positioning Crankin in a specific point in time, means remembering roughly where he will be situated in relation to the physical crank. On some dates, this amounts to ensuring the crank starts in the same spot on each attempt to try and enact some semblance of actualised muscle memory. The advice of some to simply crank as quickly as possible and listen to sound cues to know when to slow down, generally works as well but tighter sequences still require specificity of movement. Needing to move to specific frames/times would be tedious with conventional controls, but the crank makes it exceedingly natural and easy to do. The physical act of speeding up or slowing down your cranking is a tremendous joy that promotes a oneness with Crankin.

Aesthetically, Crankin Presents is starkly contrasted against most other Playdate titles. Rather than black on white, everything is presented in white on black which is gorgeous. The high level of detail (or at least smoothness) means nothing reads as pixellated, but that avoidance of chunky pixels means hitboxes are exacting and occasionally unforgiving. This is most pronounced with Poopy-kun. Being so much smaller than most other hazards (and situated near the constant ambulation of Crankin's legs), this tiny guy represents one of the greatest headaches despite being my favourite character. The particles emanating from him are themselves part of the hitbox, but as singular pixels they are often difficult to see or understand where they are in relation to Crankin. Poopy-kun's exacting demands are not often the sole reason for failure, but he is nonetheless testament to the potential issues of favouring fidelity over clarity on the Playdate.

If the difficulty were not enough of a departure, the sound design also makes Crankin Presents stand out from Takahashi's gameography. There is no music, and the only sounds are your footsteps accompanied by pitch-shifting "One, two" chants, and the indicators of obstacles. Curiously, I think this is entirely to its benefit as a title on a pick-up-and-play device. While I lose something by not having the sound on, I don't lose everything like I would with Wattam or Katamari. For those titles their sound is perhaps less important for their gameplay, but so much more vital to their identity. I love the squeakiness of Crankin Presents, but I'm not getting a fundamentally lesser experience if I play in its absence.

The greatest joy of Crankin Presents is its surprises. Those 'A-ha!' moments of discovering how a specific animation can be used for a multitude of obstacles, or the realisation that supposedly superficial graphical pleasantries serve gameplay functions as well. Those feelings of thinking the game surely must be done only for there to be so many more dates. Those ever-present subversions of level expectations. And in true Keita Takahashi fashion, coming away from a 100% par-time completion realising there was no extrinsic reward for doing so, only a profound sense of self-satisfaction in taking this meticulously designed mechanical toy and figuring out how every part of it ticks. The Mechanical Turk has been dismantled only for me to realise how human it was all along.

The only instance in Keita Takahashi's oeuvre of overt difficulty and challenge. Whereas stages in Katamari Damacy and We Love Katamari occasionally presented the player with moments that tested their skill and know-how -- primarily in the former's Ursa Major and Taurus levels, the latter's Cowbear request -- Crankin Presents Time Travel Adventure offers little of the toy-like reprieve found in Takahashi's other titles. This has no doubt caught most Playdate owners off-guard, particularly those who, like me, picked up a Playdate almost exclusively for a new digital Takahashi playground. What we received instead is a (literally) mechanically intense movement-based, animation-frame-dependent dodge-em-up featuring memorisation and routing like one would expect from Gradius, with the pixel perfect precision of I Want To Be The Guy in a coat of Wattam paint.

Here more than with any other Playdate title, the specifics of the crank must be appreciated. Like an electromechanical re-imagining of a well-oiled wooden crank toy, the rotation is smooth and defined with just enough resistance to keep it steady when not being turned. This is critical in Crankin Presents as it means each position of the crank at a point in time correlates exactly with a state in Crankin's timeline. Rotating the crank, say, exactly 476.2 degrees, then cranking it the other way 476.2 degrees back puts me in the exact same frame of animation, the same location I was in. This results in two layers of memorisation being demanded of the player.

On a macro level, many date's layouts must be roughly mentally mapped out to understand where hazards are, and where they can be avoided. On the micro level, each attempt's variations in where your cranking starts and ends, and the need for positioning Crankin in a specific point in time, means remembering roughly where he will be situated in relation to the physical crank. On some dates, this amounts to ensuring the crank starts in the same spot on each attempt to try and enact some semblance of actualised muscle memory. The advice of some to simply crank as quickly as possible and listen to sound cues to know when to slow down, generally works as well but tighter sequences still require specificity of movement. Needing to move to specific frames/times would be tedious with conventional controls, but the crank makes it exceedingly natural and easy to do. The physical act of speeding up or slowing down your cranking is a tremendous joy that promotes a oneness with Crankin.

Aesthetically, Crankin Presents is starkly contrasted against most other Playdate titles. Rather than black on white, everything is presented in white on black which is gorgeous. The high level of detail (or at least smoothness) means nothing reads as pixellated, but that avoidance of chunky pixels means hitboxes are exacting and occasionally unforgiving. This is most pronounced with Poopy-kun. Being so much smaller than most other hazards (and situated near the constant ambulation of Crankin's legs), this tiny guy represents one of the greatest headaches despite being my favourite character. The particles emanating from him are themselves part of the hitbox, but as singular pixels they are often difficult to see or understand where they are in relation to Crankin. Poopy-kun's exacting demands are not often the sole reason for failure, but he is nonetheless testament to the potential issues of favouring fidelity over clarity on the Playdate.

If the difficulty were not enough of a departure, the sound design also makes Crankin Presents stand out from Takahashi's gameography. There is no music, and the only sounds are your footsteps accompanied by pitch-shifting "One, two" chants, and the indicators of obstacles. Curiously, I think this is entirely to its benefit as a title on a pick-up-and-play device. While I lose something by not having the sound on, I don't lose everything like I would with Wattam or Katamari. For those titles their sound is perhaps less important for their gameplay, but so much more vital to their identity. I love the squeakiness of Crankin Presents, but I'm not getting a fundamentally lesser experience if I play in its absence.

The greatest joy of Crankin Presents is its surprises. Those 'A-ha!' moments of discovering how a specific animation can be used for a multitude of obstacles, or the realisation that supposedly superficial graphical pleasantries serve gameplay functions as well. Those feelings of thinking the game surely must be done only for there to be so many more dates. Those ever-present subversions of level expectations. And in true Keita Takahashi fashion, coming away from a 100% par-time completion realising there was no extrinsic reward for doing so, only a profound sense of self-satisfaction in taking this meticulously designed mechanical toy and figuring out how every part of it ticks. The Mechanical Turk has been dismantled only for me to realise how human it was all along.

Frisson rendered concrete.

The impending release of Wrath of the Lich King Classic has sent a prevailing wind of ennui through my being. A little over a year ago I deleted my Battle.net account. Activision Blizzard's handling of the Blitzchung situation, the news breaking of their abuses towards employees, the disaster that was Warcraft III Reforged, the patronising announcement of Diablo Immortal, Heroes of the Storm entering maintenance mode, the unmitigated mess that was Battle for Azeroth, the notion of an Overwatch 2, the ballooning of the WoW cash shop, the insistence on annual subscriptions, the time gating of content, the borrowed power systems, the lore trash fire of Shadowlands, and the ostentatious claim of Eternity's End being the 'Final Chapter' of a supposed Warcraft 3 saga, in an attempt to combat Final Fantasy XIV: Endwalker's Hydaelyn and Zodiark saga all broke the proverbial camel's back. This was not a spontaneous act. This was a deliberate decision on my part to fundamentally erase the record of my participation in a game I spent over half my life with. I've permanently denied myself the possibility of returning to something I loved with my entire being. Wrath of the Lich King Classic theoretically extends a hand from the beyond to welcome me home, but despite what Blizzard might propose, I can never go back. No one can ever go back.

It is this memory of Arthas that I choose to keep in my heart.

Others learned of the unlivability of a reborn nostalgia with World of Warcraft Classic and Burning Crusade Classic, but that original game and its expansion were before my time. They were antiquated in comparison to Wrath of the Lich King. Wrath of the Lich King was a direct continuation of Warcraft III: The Frozen Throne, rather than just a tale within that realm. This wasn't some hodgepodge of rote item collection to counter minor threats, or the battling of foes so literally alien as to be largely irrelevant to me and my character. This was a considered effort to contend with the horrors of the past, an opportunity to feel like an active participant in an era-defining event.

Wait... I remember you... in the mountains.

The issue of reviving these past experiences is that their original forms were borne into a more naive time. Old School Runescape demonstrated before World of Warcraft Classic the ills of older MMO design in a hyper-online world. Whereas our playing of Runescape in 2007 was informed by rumours and assumptions of what was and could be possible, 2007scape exists in a world where every iota of information is readily documented. 2013 and 2022 are not the time of Zezima, of Unregistered HyperCam 2, of proto-Machinimas, of frag videos, of fishing for lobbies in Catherby for hours, of playing the game for the fun of itself rather than to 'succeed'. What Old School Runescape taught us a decade ago was that, as Sid Meier put it, "Many players cannot help approaching a game as an optimization puzzle. Given the opportunity, players will optimize the fun out of a game." I am not so oblivious as to claim people had not already done this in Runescape, but without the omnipresence of YouTube open-mouth thumbnails and Reddit megathreads, your average player probably wasn't min-maxing then as they would now. Old School Runescape is perhaps the most perfect representation of efficiency being the game itself, like Factorio if it were a fantasy MMORPG. It has become an antisocial MMO experience, because socialising is itself inefficient. And yet, World of Warcraft Classic came out only to suffer the exact same problems.

A hero, that's what you once were.

The core issue with recuscitating the original World of Warcraft experience is, I think, one of iteration rather than of inversion. Players clamored for a return to 2007 Runescape because the game had fundamentally changed in no small part because of Summoning and the Evolution of Combat update. It was no longer the point and click, set and forget MMO of yesteryear, but an involved, cooldown based, hotbar experience. World of Warcraft on the other hand has always been basically the same game, improving (mostly) with each patch and expansion, iterating on that foundation. To be sure, the WoW of 2019 was radically different from its 15 years gone forebear, but it wasn't a completely different package sold as something else. Reduced to its base elements, both versions of the game are the same. A different flavour of chocolate, but chocolate all the same. What made the 'Classic' experience so great when remembered was that WoW was novel for so many. The notion of a massive world you could explore with others, all interconnected with no loading screens (outside of instances/teleporting), with forty player raids, with an air of discoverability was specific to the time period. Thottbot existed, but not everyone needed (or felt they needed) to use it, and its data was primarily anecdotal rather than informed by hard statistics. With fifteen years of info at our fingertips, the Classic experience quite literally can't be reproduced, just as the Runescape of 2007 remains firmly in historic memory.

This is the hour of their ascension. This is the hour of your dark rebirth...

With the fun optimised out of World of Warcraft, and without substantive novel content outside of forty player raiding and untouched questing, the playerbase rather quickly turned apathetic towards Classic. It did not, and could not, live up to that memory, and it left Blizzard in a tricky position. Without updates, Classic had little to keep players invested. With Old School Runescape style updates, it would not be the World of Warcraft of yore. The solution, it seems, was to have a divergent path. World of Warcraft Classic would persist, with players having the option to continue to Burning Crusade Classic. This is well and good on the surface, but it was soured by the Digital Deluxe edition's inclusion of a character boost, in-game cosmetic items, and a new mount. Even ignoring the addition of items which didn't exist in the original release, the character boost alone betrayed the supposed ethos of the Classic experience. As a means of preventing players from missing out on that initial rush of the expansion's release, a boost isn't intrinsically a bad thing, but it being locked behind a paywall made the playing field uneven. This was no longer about reliving bygone days, this was about a fear of missing out, this was a chance to rush to the destination, rather than revel in the journey itself.

I will treasure it always - a moment of time that will be lost forever.

The same thing is going to occur with Wrath of the Lich King Classic. I was only 11 when I started playing WoW. Ulduar had just been added to the game. I couldn't have cared less about optimisation. I made numerous characters and ambled around aimlessly. I played comically poorly. I drew my characters on looseleaf. I was so excited and enthralled by this world which stretched before me. Eventually settling on a Tauren Hunter, every moment of the game was precious. As a child, it was a formative experience. I can still remember struggling with the quest Mazzranache, entering the Barrens for the first time, seeing gold sellers float auspiciously in Orgrimmar, killing dinosaurs in Un'Goro Crater, wondering where all the quests were in Silithus. Outlands never grabbed me quite the same way perhaps because of its contrast with Azeroth itself, with its inhabitants whose problems were literally a world away. When I reached the prerequisite level, I created a Death Knight. The random name generator bestowed upon me a moniker I still use to this day, Chuulimta. The starting zone genuinely shook me, at once appealing to my prepubescent desire to commit virtual atrocities while making it crystal clear that these horrors exacerbated the problems of the realm. I was hindering the world I wished to save. And when I eventually stepped on the zeppelin bound for the Howling Fjord, and gazed upon those verdant cliffs, I was agog at the quiet beauty of it all.

For you, I would give my life a thousand times.

I was actively helping an effort to rid the world of an unspeakable terror. And yet, I was also able to find moments of levity and calm. It's almost laughable in retrospect, to think I was having an appreciable effect on anything in this virtual landscape at the peak of WoW's popularity, but it felt and feels real after all this time. Even imagining the nyckelharpa of the Grizzly Hills theme, or those claustrophobic peaks in The Storm Peaks, or the amber grasses of Borean Tundra, or the bustle of Dalaran, those recollections rend my heart in twain. This frigid land clinging to life in the face of decay was home. At a time of change for me and my family, Northrend was my constant.

Do with it as you please, but do not forget those that assisted you in this monumental feat.

At a time of friendlessness, Wrath of the Lich King afforded me social opportunities, however fragmentary, that kept me moving forward. Names flitter away from my grasp, their recall an impossibility by now. The familiar faces when I would fish, those smile-inducing comrades who would greet me when I logged in, those scant few who would run content with me for no gain outside of the pleasure of the act itself. They will never return to me, nor I to them. And that atmosphere will not for anyone. The compartmentalising of social gaming into Discord servers and group chats forbids that earnest connection with the unfamiliar other outright. Just as in Old School Runescape, the game might be massively multiplayer, but it has become more solitary than ever.

Leave me. I have much to ponder.

I didn't kill the Lich King until much later, around Mists of Pandaria. I had seen so much of Icecrown Citadel, completing every fight up to the Lich King, but its mechanics were beyond me until I vastly outleveled, and outgeared it. Even with a statistical advantage, I wasn't able to do it alone. I brought along a friend who had just been getting into WoW. For him it was the first time starting ICC, for me it was the first time bringing the tale of Arthas to a close. When Arthas was felled and that iconic cutscene played, I was moved to tears. I had closed the loop on such an important part of my life. From then on, I would and could only have the memory, for there was naught left for me to find.

Alas... you give me a greater gift than you know.

Each expansion of World of Warcraft sees the outgoing content largely deprecated and abandoned. This only compounds, making it all the less likely you will encounter someone in an old expansion as time shambles on. Like revisiting your childhood home, this makes going back to see what once was gut wrenching. It was such a simple time, one of joy. It was an experience that can never be relived, by me or by anyone.

At last, I am able to lay my eyes upon you again.

Shortly before I logged out of World of Warcraft for what would, unbeknownst to me, be the last time, I flew across Northrend, descending into Wintergrasp to take in one of my favourite pieces of music. Crested on a snowy mound, an unfamiliar face landed beside me silently, and offered to me one word.

"Hey."

That was, and always will be, enough.

The impending release of Wrath of the Lich King Classic has sent a prevailing wind of ennui through my being. A little over a year ago I deleted my Battle.net account. Activision Blizzard's handling of the Blitzchung situation, the news breaking of their abuses towards employees, the disaster that was Warcraft III Reforged, the patronising announcement of Diablo Immortal, Heroes of the Storm entering maintenance mode, the unmitigated mess that was Battle for Azeroth, the notion of an Overwatch 2, the ballooning of the WoW cash shop, the insistence on annual subscriptions, the time gating of content, the borrowed power systems, the lore trash fire of Shadowlands, and the ostentatious claim of Eternity's End being the 'Final Chapter' of a supposed Warcraft 3 saga, in an attempt to combat Final Fantasy XIV: Endwalker's Hydaelyn and Zodiark saga all broke the proverbial camel's back. This was not a spontaneous act. This was a deliberate decision on my part to fundamentally erase the record of my participation in a game I spent over half my life with. I've permanently denied myself the possibility of returning to something I loved with my entire being. Wrath of the Lich King Classic theoretically extends a hand from the beyond to welcome me home, but despite what Blizzard might propose, I can never go back. No one can ever go back.

It is this memory of Arthas that I choose to keep in my heart.

Others learned of the unlivability of a reborn nostalgia with World of Warcraft Classic and Burning Crusade Classic, but that original game and its expansion were before my time. They were antiquated in comparison to Wrath of the Lich King. Wrath of the Lich King was a direct continuation of Warcraft III: The Frozen Throne, rather than just a tale within that realm. This wasn't some hodgepodge of rote item collection to counter minor threats, or the battling of foes so literally alien as to be largely irrelevant to me and my character. This was a considered effort to contend with the horrors of the past, an opportunity to feel like an active participant in an era-defining event.

Wait... I remember you... in the mountains.

The issue of reviving these past experiences is that their original forms were borne into a more naive time. Old School Runescape demonstrated before World of Warcraft Classic the ills of older MMO design in a hyper-online world. Whereas our playing of Runescape in 2007 was informed by rumours and assumptions of what was and could be possible, 2007scape exists in a world where every iota of information is readily documented. 2013 and 2022 are not the time of Zezima, of Unregistered HyperCam 2, of proto-Machinimas, of frag videos, of fishing for lobbies in Catherby for hours, of playing the game for the fun of itself rather than to 'succeed'. What Old School Runescape taught us a decade ago was that, as Sid Meier put it, "Many players cannot help approaching a game as an optimization puzzle. Given the opportunity, players will optimize the fun out of a game." I am not so oblivious as to claim people had not already done this in Runescape, but without the omnipresence of YouTube open-mouth thumbnails and Reddit megathreads, your average player probably wasn't min-maxing then as they would now. Old School Runescape is perhaps the most perfect representation of efficiency being the game itself, like Factorio if it were a fantasy MMORPG. It has become an antisocial MMO experience, because socialising is itself inefficient. And yet, World of Warcraft Classic came out only to suffer the exact same problems.

A hero, that's what you once were.

The core issue with recuscitating the original World of Warcraft experience is, I think, one of iteration rather than of inversion. Players clamored for a return to 2007 Runescape because the game had fundamentally changed in no small part because of Summoning and the Evolution of Combat update. It was no longer the point and click, set and forget MMO of yesteryear, but an involved, cooldown based, hotbar experience. World of Warcraft on the other hand has always been basically the same game, improving (mostly) with each patch and expansion, iterating on that foundation. To be sure, the WoW of 2019 was radically different from its 15 years gone forebear, but it wasn't a completely different package sold as something else. Reduced to its base elements, both versions of the game are the same. A different flavour of chocolate, but chocolate all the same. What made the 'Classic' experience so great when remembered was that WoW was novel for so many. The notion of a massive world you could explore with others, all interconnected with no loading screens (outside of instances/teleporting), with forty player raids, with an air of discoverability was specific to the time period. Thottbot existed, but not everyone needed (or felt they needed) to use it, and its data was primarily anecdotal rather than informed by hard statistics. With fifteen years of info at our fingertips, the Classic experience quite literally can't be reproduced, just as the Runescape of 2007 remains firmly in historic memory.

This is the hour of their ascension. This is the hour of your dark rebirth...

With the fun optimised out of World of Warcraft, and without substantive novel content outside of forty player raiding and untouched questing, the playerbase rather quickly turned apathetic towards Classic. It did not, and could not, live up to that memory, and it left Blizzard in a tricky position. Without updates, Classic had little to keep players invested. With Old School Runescape style updates, it would not be the World of Warcraft of yore. The solution, it seems, was to have a divergent path. World of Warcraft Classic would persist, with players having the option to continue to Burning Crusade Classic. This is well and good on the surface, but it was soured by the Digital Deluxe edition's inclusion of a character boost, in-game cosmetic items, and a new mount. Even ignoring the addition of items which didn't exist in the original release, the character boost alone betrayed the supposed ethos of the Classic experience. As a means of preventing players from missing out on that initial rush of the expansion's release, a boost isn't intrinsically a bad thing, but it being locked behind a paywall made the playing field uneven. This was no longer about reliving bygone days, this was about a fear of missing out, this was a chance to rush to the destination, rather than revel in the journey itself.

I will treasure it always - a moment of time that will be lost forever.

The same thing is going to occur with Wrath of the Lich King Classic. I was only 11 when I started playing WoW. Ulduar had just been added to the game. I couldn't have cared less about optimisation. I made numerous characters and ambled around aimlessly. I played comically poorly. I drew my characters on looseleaf. I was so excited and enthralled by this world which stretched before me. Eventually settling on a Tauren Hunter, every moment of the game was precious. As a child, it was a formative experience. I can still remember struggling with the quest Mazzranache, entering the Barrens for the first time, seeing gold sellers float auspiciously in Orgrimmar, killing dinosaurs in Un'Goro Crater, wondering where all the quests were in Silithus. Outlands never grabbed me quite the same way perhaps because of its contrast with Azeroth itself, with its inhabitants whose problems were literally a world away. When I reached the prerequisite level, I created a Death Knight. The random name generator bestowed upon me a moniker I still use to this day, Chuulimta. The starting zone genuinely shook me, at once appealing to my prepubescent desire to commit virtual atrocities while making it crystal clear that these horrors exacerbated the problems of the realm. I was hindering the world I wished to save. And when I eventually stepped on the zeppelin bound for the Howling Fjord, and gazed upon those verdant cliffs, I was agog at the quiet beauty of it all.

For you, I would give my life a thousand times.

I was actively helping an effort to rid the world of an unspeakable terror. And yet, I was also able to find moments of levity and calm. It's almost laughable in retrospect, to think I was having an appreciable effect on anything in this virtual landscape at the peak of WoW's popularity, but it felt and feels real after all this time. Even imagining the nyckelharpa of the Grizzly Hills theme, or those claustrophobic peaks in The Storm Peaks, or the amber grasses of Borean Tundra, or the bustle of Dalaran, those recollections rend my heart in twain. This frigid land clinging to life in the face of decay was home. At a time of change for me and my family, Northrend was my constant.

Do with it as you please, but do not forget those that assisted you in this monumental feat.

At a time of friendlessness, Wrath of the Lich King afforded me social opportunities, however fragmentary, that kept me moving forward. Names flitter away from my grasp, their recall an impossibility by now. The familiar faces when I would fish, those smile-inducing comrades who would greet me when I logged in, those scant few who would run content with me for no gain outside of the pleasure of the act itself. They will never return to me, nor I to them. And that atmosphere will not for anyone. The compartmentalising of social gaming into Discord servers and group chats forbids that earnest connection with the unfamiliar other outright. Just as in Old School Runescape, the game might be massively multiplayer, but it has become more solitary than ever.

Leave me. I have much to ponder.

I didn't kill the Lich King until much later, around Mists of Pandaria. I had seen so much of Icecrown Citadel, completing every fight up to the Lich King, but its mechanics were beyond me until I vastly outleveled, and outgeared it. Even with a statistical advantage, I wasn't able to do it alone. I brought along a friend who had just been getting into WoW. For him it was the first time starting ICC, for me it was the first time bringing the tale of Arthas to a close. When Arthas was felled and that iconic cutscene played, I was moved to tears. I had closed the loop on such an important part of my life. From then on, I would and could only have the memory, for there was naught left for me to find.

Alas... you give me a greater gift than you know.

Each expansion of World of Warcraft sees the outgoing content largely deprecated and abandoned. This only compounds, making it all the less likely you will encounter someone in an old expansion as time shambles on. Like revisiting your childhood home, this makes going back to see what once was gut wrenching. It was such a simple time, one of joy. It was an experience that can never be relived, by me or by anyone.

At last, I am able to lay my eyes upon you again.

Shortly before I logged out of World of Warcraft for what would, unbeknownst to me, be the last time, I flew across Northrend, descending into Wintergrasp to take in one of my favourite pieces of music. Crested on a snowy mound, an unfamiliar face landed beside me silently, and offered to me one word.

"Hey."

That was, and always will be, enough.

1981

ヘイヘイホー ヘイヘイホー

「hei hei hou, hei hei hou」

You're probably never going to play Yosaku. Nobody will. It appears only in scant screenshots, an arcade flyer, mention in SNK 40th Anniversary Collection, as an easter egg in The King of Fighters: Battle de Paradise, and demonstrated in a single YouTube video. Releasing shortly before Safari Rally and Ozma Wars, Yosaku remains undumped (if not entirely lost) alongside SNK's earliest 'Micon Kit' Breakout clones. In spite of its obscurity, Yosaku is a foundational game not just for SNK, but for the early Japanese games market as a whole.

ヘイヘイホー ヘイヘイホー

「hei hei hou, hei hei hou」

The premise of Yosaku is pretty simple. The player is a lumberjack, toiling away in the forest while branches fall, birds defecate, boars charge, and snakes slither. Avoid danger, chop the trees, get a high score. It is by no means groundbreaking but for a 1979 release it seems to be decently fun. What is fascinating about Yosaku stems from what inspired it: an Enka song popularised by Saburou Kitajima in 1978.

トントントン トントントン

「tontonton, tontonton」

One of Sabu-chan's most famous works, Yosaku similarly tells the basic tale of the titular Yosaku chipping away at a tree while his wife performs domestic duties. Written by religious scholar and critic Kiminori Nanasawa, Yosaku was a submission to the long-running NHK musical variety show Anata no Melody. The conceit of the program was that amateur songwriters would submit their work to be performed by professional musicians. Yosaku's sparse lyrics are abound with onomotapoeia, and it's just a great track overall. In fact, the game Yosaku features part of the melody of the song Yosaku as sung by Sabu-chan, and it's officially licensed from the Japanese Society for Rights of Authors, Composers and Publishers, one of the first video games to bear their legal blessing.

トントントン トントントン

「tontonton, tontonton」

Lest we forget, this was the era of the arcade clone. Perhaps in a cruel twist of irony then for a company founded on Breakout clones, Yosaku is known less for its arcade release, and more for the unlicensed, unsanctioned copycat which released at the launch of the Epoch Cassette Vision. Kikori no Yosaku sees the detailed SNK original reduced to its barest geometries and most base elements. The much chunkier graphics reduce the playfield to just two trees instead of Yosaku's three. Unable to litter the space with smaller but more plentiful hazards, Kikori no Yosaku's dangers are the unhewn log to Yosaku's two-by-four. Rather than allow Yosaku to hide behind trees, Epoch's version leaps over boars. And even without the legal go ahead, Kikori no Yosaku has a crude rendition of those same bars from Sabu-chan's hit song.

ホーホー ホーホー

「houhou, houhou」

The Epoch Cassette Vision held 70% of the games console market in Japan by 1982. 'Video Games Console Library' makes the unsubstantiated claim that Kikori no Yosaku was the game that made the Cassette Vision as successful as it was. It's impossible to concretely corroborate this, but considering it was a launch title (and labelled as #1), it would certainly have drawn some customers in. Furthermore, Cassette Vision game releases were glacial, being made in-house by only three developers with a new title hitting shelves every quarter. An interview with Epoch designer and supervisor Masayuki Horie similarly asserts that Kikori no Yosaku is the first game people talk about when the Cassette Vision is discussed. Horie mentions that industry shows saw developers trying to discern which games would be popular, and thus fit for cloning, so Kikori no Yosaku's significance may well be true.

ヘイヘイホー ヘイヘイホー

「hei hei hou, hei hei hou」

With such a storied past, one might want to play Kikori no Yosaku for themselves. Well, you're probably never going to play the Cassette Vision release of Kikori no Yosaku, and not for lack of trying. A key quirk of the Cassette Vision is that the console itself is effectively just an AV passthrough. It lacks a processor. Unlike with other cartridge-based systems, Cassette Vision games house the software and hardware which allowed vastly faster operation. This means emulation is, while not impossible, entirely too cumbersome for anyone to have meaningfully tackled it thus far - ROM dumps for all eleven releases do now exist at least. Barring the purchase of antiquated hardware, Kikori no Yosaku is just as playable as Yosaku.

ヘイヘイホー ヘイヘイホー

「hei hei hou, hei hei hou」

Or so I thought. As it turns out, an unofficial port of Kikori no Yosaku came to the Sharp X68000 in 1991 thanks to IJI Team. This clone of a clone is a near-exact recreation of the Cassette Vision original, down to the graphical quirks of diagonal sprites. The only substantial difference I was able to spot has to do with the colours themselves, which are more pastel on Cassette Vision than they are on X68000 - this may be due to the oddities of RF connections.

トントントン トントントン

「tontonton, tontonton」

All told, Kikori no Yosaku is a pretty fun romp, albeit a pretty easy one when not playing on the higher difficulties. The circumstances of its creation as a clone of an oddly seminal title, which itself is only accessible thanks to another clone, make it noteworthy. Furthermore, the X68000 version is the only such recreation of an Epoch Cassette Vision game. Even the absurd Pac-Man clone PakPak Monster remains bound to the original hardware.

トントントン トントントン

「tontonton, tontonton」

Yosaku is a hit enka song written by an obscure amateur.

Yosaku is one of the only lost SNK titles.

Yosaku is one of the first games to have music licensed by JASRAC.

Yosaku is perhaps responsible for the success of the Epoch Cassette Vision.

Yosaku is emblematic of the wild west of early video game (non)copyright.

Yosaku is a chunky, shameless copy.

Yosaku is a near-perfect recreation.

Yosaku is simple but elegant.

ホーホー ホーホー

「houhou, houhou」

「hei hei hou, hei hei hou」

You're probably never going to play Yosaku. Nobody will. It appears only in scant screenshots, an arcade flyer, mention in SNK 40th Anniversary Collection, as an easter egg in The King of Fighters: Battle de Paradise, and demonstrated in a single YouTube video. Releasing shortly before Safari Rally and Ozma Wars, Yosaku remains undumped (if not entirely lost) alongside SNK's earliest 'Micon Kit' Breakout clones. In spite of its obscurity, Yosaku is a foundational game not just for SNK, but for the early Japanese games market as a whole.

ヘイヘイホー ヘイヘイホー

「hei hei hou, hei hei hou」

The premise of Yosaku is pretty simple. The player is a lumberjack, toiling away in the forest while branches fall, birds defecate, boars charge, and snakes slither. Avoid danger, chop the trees, get a high score. It is by no means groundbreaking but for a 1979 release it seems to be decently fun. What is fascinating about Yosaku stems from what inspired it: an Enka song popularised by Saburou Kitajima in 1978.

トントントン トントントン

「tontonton, tontonton」

One of Sabu-chan's most famous works, Yosaku similarly tells the basic tale of the titular Yosaku chipping away at a tree while his wife performs domestic duties. Written by religious scholar and critic Kiminori Nanasawa, Yosaku was a submission to the long-running NHK musical variety show Anata no Melody. The conceit of the program was that amateur songwriters would submit their work to be performed by professional musicians. Yosaku's sparse lyrics are abound with onomotapoeia, and it's just a great track overall. In fact, the game Yosaku features part of the melody of the song Yosaku as sung by Sabu-chan, and it's officially licensed from the Japanese Society for Rights of Authors, Composers and Publishers, one of the first video games to bear their legal blessing.

トントントン トントントン

「tontonton, tontonton」

Lest we forget, this was the era of the arcade clone. Perhaps in a cruel twist of irony then for a company founded on Breakout clones, Yosaku is known less for its arcade release, and more for the unlicensed, unsanctioned copycat which released at the launch of the Epoch Cassette Vision. Kikori no Yosaku sees the detailed SNK original reduced to its barest geometries and most base elements. The much chunkier graphics reduce the playfield to just two trees instead of Yosaku's three. Unable to litter the space with smaller but more plentiful hazards, Kikori no Yosaku's dangers are the unhewn log to Yosaku's two-by-four. Rather than allow Yosaku to hide behind trees, Epoch's version leaps over boars. And even without the legal go ahead, Kikori no Yosaku has a crude rendition of those same bars from Sabu-chan's hit song.

ホーホー ホーホー

「houhou, houhou」

The Epoch Cassette Vision held 70% of the games console market in Japan by 1982. 'Video Games Console Library' makes the unsubstantiated claim that Kikori no Yosaku was the game that made the Cassette Vision as successful as it was. It's impossible to concretely corroborate this, but considering it was a launch title (and labelled as #1), it would certainly have drawn some customers in. Furthermore, Cassette Vision game releases were glacial, being made in-house by only three developers with a new title hitting shelves every quarter. An interview with Epoch designer and supervisor Masayuki Horie similarly asserts that Kikori no Yosaku is the first game people talk about when the Cassette Vision is discussed. Horie mentions that industry shows saw developers trying to discern which games would be popular, and thus fit for cloning, so Kikori no Yosaku's significance may well be true.

ヘイヘイホー ヘイヘイホー

「hei hei hou, hei hei hou」

With such a storied past, one might want to play Kikori no Yosaku for themselves. Well, you're probably never going to play the Cassette Vision release of Kikori no Yosaku, and not for lack of trying. A key quirk of the Cassette Vision is that the console itself is effectively just an AV passthrough. It lacks a processor. Unlike with other cartridge-based systems, Cassette Vision games house the software and hardware which allowed vastly faster operation. This means emulation is, while not impossible, entirely too cumbersome for anyone to have meaningfully tackled it thus far - ROM dumps for all eleven releases do now exist at least. Barring the purchase of antiquated hardware, Kikori no Yosaku is just as playable as Yosaku.

ヘイヘイホー ヘイヘイホー

「hei hei hou, hei hei hou」

Or so I thought. As it turns out, an unofficial port of Kikori no Yosaku came to the Sharp X68000 in 1991 thanks to IJI Team. This clone of a clone is a near-exact recreation of the Cassette Vision original, down to the graphical quirks of diagonal sprites. The only substantial difference I was able to spot has to do with the colours themselves, which are more pastel on Cassette Vision than they are on X68000 - this may be due to the oddities of RF connections.

トントントン トントントン

「tontonton, tontonton」

All told, Kikori no Yosaku is a pretty fun romp, albeit a pretty easy one when not playing on the higher difficulties. The circumstances of its creation as a clone of an oddly seminal title, which itself is only accessible thanks to another clone, make it noteworthy. Furthermore, the X68000 version is the only such recreation of an Epoch Cassette Vision game. Even the absurd Pac-Man clone PakPak Monster remains bound to the original hardware.

トントントン トントントン

「tontonton, tontonton」

Yosaku is a hit enka song written by an obscure amateur.

Yosaku is one of the only lost SNK titles.

Yosaku is one of the first games to have music licensed by JASRAC.

Yosaku is perhaps responsible for the success of the Epoch Cassette Vision.

Yosaku is emblematic of the wild west of early video game (non)copyright.

Yosaku is a chunky, shameless copy.

Yosaku is a near-perfect recreation.

Yosaku is simple but elegant.

ホーホー ホーホー

「houhou, houhou」

1993

I love the Columns III guy. I think about Columns III guy all the time. Columns III guy's bizarre pose on a pile of jewels astounds me. Columns III guy's legs are comically long in relation to Columns III guy's torso, like a bizarro inversion of Tim Conway's Dorf character. Is it because Columns III guy's shirt is too big or of a weird cut? Are Columns III guy's pants too big? Is Columns III guy just relaxed and slouched atop his jewelled throne? On the cover, on the cart, on the manual, in the advertising materials, Columns III guy shrugs with a lackadaisical attitude which betrays the apparent mastery over Columns III that Columns III guy has, the jewels encircling him like the Chaos Emeralds in the hands of Dr. Eggman. Columns III guy does not need to sneer at us to convey his power, however, as his smile, wristwatch, and trainers let us know he is above traditional signifiers of strength. This is not to suggest Columns III guy lacks his own struggles. Columns III guy collaborates with his four doppelgangers in vague cooperation in a print ad for Columns III demonstrating Columns III's five-player multiplayer. Columns III guy labours therein while still being so sure of his victory that one Columns III guy recreates the cover Columns III guy's pose. Were his quintupled presence not enough to show the magnitude of Columns III guy's skill and importance, a sixth Columns III guy appears in the corner of the advertisement on the cover for Columns III, blown up to comical proportions so even this small representation can impart the critical role Columns III guy plays. Yet as necessary as Columns III guy is to the enjoyment of Columns III, he does not appear in any form in the game itself. His physical presence is not necessary, as Columns III guy has no doubt infiltrated the mind of the player already, leaving them knowing on a subconscious level that the game's AI is not some artificial faceless construct, it is Columns III guy. And despite the omnipresence of Columns III guy, we know nothing of Columns III guy. The only lead for an identity for Columns III guy is a single Reddit comment by a liar trying to besmirch the good name of Columns III guy. Columns III guy, my beloved, who are you, who were you? Are you there Columns III guy? It's me, Detchibe.

The game's okay.

The game's okay.

1999

Anyone with an understanding of my gaming tastes will know I heavily value:

(1) Games with novel control schemes

(2) Games which were 'firsts'

(3) Games which are obscure

(4) Games with chores

(5) Games with cooking

Ore no Ryouri is a pitch-perfect example of all the above. The cherry on top is that it is simple enough to work despite a glaring language barrier.

From the outset, Ore no Ryouri operates as an alternate take on Ape Escape's intent for the DualShock. The analog stick-centric gameplay highlights the possibilities afforded by the DualShock as a more direct and intuitive mode of player action. Whereas Ape Escape demonstrated movement alongside use of a tool, Ore no Ryouri opts for effectively mapping each arm/hand to a stick. When preparing soft serve ice cream, one stick controls the flow, the other swirls the cone. Pouring a beer involves tipping the glass and pulling the tap. Cutting means moving your stabilising hand in conjunction with your chops. Shaping a patty has your hands moving in tandem. Of course, not every kitchen task is an ambidextrous affair; ladling, salting, sauteing, etc. are done one handed. The act of turning on a fryer or burner is a simple button.

Ore no Ryouri doesn't needlessly complicate its gameplay for the sake of complexity. If anything, it seeks to reduce the involvement required for kitchen tasks. When multiples of the same ticket item are ready for frying, for example, they all get placed in the fryer at once. Pouring condiments is much the same, as is pouring broth to finish a bowl of ramen. This reduces the anxiety of the balancing act as tickets run out their respective timers, but also allows for combos by completing batches of tickets at once. Five orders of fries are fried, salted, and served as one, racking up huge points and setting the player up for stage completion or success in a cook-off.

The chores are damn great as well. Smashing roaches, dialing a rotary phone, counting money, and scrubbing dishes are all clever uses of dual analog, the latter in particular striking my fancy. A very similar dish washing chore exists in another favourite franchise of mine, Cook, Serve, Delicious! The similarity was so incredible to me that I did some quick searching and found out Vertigo Gaming's earliest projects were flash remakes of Ore no Ryouri, eventually becoming the CSD series. The feeling of Ore no Ryouri being a proto-CSD is not mere coincidence, it is a delightful truth. The transition of dual analog to a keyboard and mouse setup (and later, controller support) was elegant for that series, but I am somewhat wistful as to what CSD could be if it adhered more strictly to Ore no Ryouri's maximalism of the DualShock. Thankfully, what footage we've seen thus far of Cook Serve Forever seems to suggest it is leaning more heavily into that deliberate control rather than typing gameplay. In that sense, Ore no Ryouri has accomplished that which I wanted from Ape Escape by influencing contemporary games decades after showcasing the possibilities of play and control.

Bon appétit!

(1) Games with novel control schemes

(2) Games which were 'firsts'

(3) Games which are obscure

(4) Games with chores

(5) Games with cooking

Ore no Ryouri is a pitch-perfect example of all the above. The cherry on top is that it is simple enough to work despite a glaring language barrier.

From the outset, Ore no Ryouri operates as an alternate take on Ape Escape's intent for the DualShock. The analog stick-centric gameplay highlights the possibilities afforded by the DualShock as a more direct and intuitive mode of player action. Whereas Ape Escape demonstrated movement alongside use of a tool, Ore no Ryouri opts for effectively mapping each arm/hand to a stick. When preparing soft serve ice cream, one stick controls the flow, the other swirls the cone. Pouring a beer involves tipping the glass and pulling the tap. Cutting means moving your stabilising hand in conjunction with your chops. Shaping a patty has your hands moving in tandem. Of course, not every kitchen task is an ambidextrous affair; ladling, salting, sauteing, etc. are done one handed. The act of turning on a fryer or burner is a simple button.

Ore no Ryouri doesn't needlessly complicate its gameplay for the sake of complexity. If anything, it seeks to reduce the involvement required for kitchen tasks. When multiples of the same ticket item are ready for frying, for example, they all get placed in the fryer at once. Pouring condiments is much the same, as is pouring broth to finish a bowl of ramen. This reduces the anxiety of the balancing act as tickets run out their respective timers, but also allows for combos by completing batches of tickets at once. Five orders of fries are fried, salted, and served as one, racking up huge points and setting the player up for stage completion or success in a cook-off.

The chores are damn great as well. Smashing roaches, dialing a rotary phone, counting money, and scrubbing dishes are all clever uses of dual analog, the latter in particular striking my fancy. A very similar dish washing chore exists in another favourite franchise of mine, Cook, Serve, Delicious! The similarity was so incredible to me that I did some quick searching and found out Vertigo Gaming's earliest projects were flash remakes of Ore no Ryouri, eventually becoming the CSD series. The feeling of Ore no Ryouri being a proto-CSD is not mere coincidence, it is a delightful truth. The transition of dual analog to a keyboard and mouse setup (and later, controller support) was elegant for that series, but I am somewhat wistful as to what CSD could be if it adhered more strictly to Ore no Ryouri's maximalism of the DualShock. Thankfully, what footage we've seen thus far of Cook Serve Forever seems to suggest it is leaning more heavily into that deliberate control rather than typing gameplay. In that sense, Ore no Ryouri has accomplished that which I wanted from Ape Escape by influencing contemporary games decades after showcasing the possibilities of play and control.

Bon appétit!

2022

My doomer phase is largely over by now.

I used to doomscroll endlessly on r/collapse.

I was enamoured by arctic-news.blogspot.com, a site which has baselessly claimed for over a decade that within four years, global temperatures will rise up to 18°C.

I cried at the Arctic death spiral.

I refreshed the NSIDC's charts daily, fearing that descending line would plummet below the 2012 threshold.

I watched carbon clocks in terror.

I checked Climate Reanalyzer and was agog at global hot zones.

I devoured Peter Wadhams' A Farewell to Ice, Extinction Rebellion's This is Not a Drill, Nathaniel Rich's Losing Earth, and David Wallace-Wells' The Uninhabitable Earth.

I scared my therapist with my talk of climate catastrophe.

That's not to say that I'm entirely past that phase of my life. I still regularly check the NSIDC and Climate Reanalyzer. I read IPCC reports. But I'm a little better informed now on the realities of climate collapse. I know shit is currently hitting the fan. But I also know that, no matter what happens, I lived, and I was here. I know it isn't my fault. I know that my efforts to save some fragment of the planet might be in vain, but it can still make me feel better. I do litter clean-up on the side of the roads near me. They still fill with trash after, but for a brief moment in time they look beautiful.

And while I can push to the side of my brain those qualms about sea ice and desertification and microplastics, I can never get the smoke out of my head, out of my nose, out of my lungs.