PasokonDeacon

2013

To some, Hydlide's redemption. To me, a reminder of what already worked. Revived-lyde, if you will. /dadjoke

Nostalgia is a fickle thing to design around. Lean too hard on it and your game's core will collapse under the pressure of memories. Promise but under-deliver and you'll turn players off in due time. Fairune isn't a lot more than polished pastiche-cum-homage, but I believe it takes the premise of 1984's Hydlide & adjacent games to near its limits. All the old elements are here, just refined for a newer, more critical audience.

Yes, once upon a time in a land not so far away, game fans got a lot of enjoyment from the most basic of adventures with stat progression. Hydlide took its essentials from Tower of Druaga, placing that game's schoolyard secrets manifesto into a home play venue. This makes it difficult, if not frustrating to play today for anyone expecting what most consider intuitive design. That said, I think too many dismiss not just what Hydlide accomplished in its time, but how elegant it was & still is. Sure, you're bumbling around an overworld & dungeons looking for any possible hint towards progress. But in this way, it succeeds in mixing the classic adventure, puzzle, & dungeon crawling genres, creating a journey both timely yet archetypal.

If Hydlide's the role-playing adventure that canon forgot (or too quickly disqualified), then Fairune's the rejuvenation of all T&E Soft's game represented. I had so much fun traversing this small but detailed land, uncovering its oddities and flowing from one power tier to the next. Here, the nostalgia comes less from simply aping its predecessors, hoping for an easy connection to players. Rather, the excellently presented fantasy world & tropes convey a kind of pre-Tolkein fiction, both celebrated & demystified. Out with the enigmatic solutions, in with the peeling skin of what Hydlide sought to achieve.

The final boss becoming a classic arcade shooter is a bit too cute, though. (Even considering Hydlide creator Tokihiro Naito's own penchant for STGs, this was too on-the-nose.) And the game can only immerse you so much into this primordial high fantasy structure without iterating on its mechanics the way Fairune 2 does. But I think Skipmore's original throwback ARPG is a panacea for any discussions revolving around Hydlide & its place in game design history. The original J-PC game made a critical leap from Druaga's coin-feeding gatekeeping to a more palatable, individualized experience you could still share with friends & other gamers. Fairune recaptures the novelty, strangeness, and sekaikan that Hydlide's fans felt in the mid-'80s, just for today's players.

Even if I much prefer the sequel for how it posits a world where Hydlide's sequels didn't overcomplicate themselves to ill end, there's every reason to replay the prequel. Do yourself a favor and try this out for size. It might have you thinking twice about laughing off proto-Zelda examples of the genre.

Nostalgia is a fickle thing to design around. Lean too hard on it and your game's core will collapse under the pressure of memories. Promise but under-deliver and you'll turn players off in due time. Fairune isn't a lot more than polished pastiche-cum-homage, but I believe it takes the premise of 1984's Hydlide & adjacent games to near its limits. All the old elements are here, just refined for a newer, more critical audience.

Yes, once upon a time in a land not so far away, game fans got a lot of enjoyment from the most basic of adventures with stat progression. Hydlide took its essentials from Tower of Druaga, placing that game's schoolyard secrets manifesto into a home play venue. This makes it difficult, if not frustrating to play today for anyone expecting what most consider intuitive design. That said, I think too many dismiss not just what Hydlide accomplished in its time, but how elegant it was & still is. Sure, you're bumbling around an overworld & dungeons looking for any possible hint towards progress. But in this way, it succeeds in mixing the classic adventure, puzzle, & dungeon crawling genres, creating a journey both timely yet archetypal.

If Hydlide's the role-playing adventure that canon forgot (or too quickly disqualified), then Fairune's the rejuvenation of all T&E Soft's game represented. I had so much fun traversing this small but detailed land, uncovering its oddities and flowing from one power tier to the next. Here, the nostalgia comes less from simply aping its predecessors, hoping for an easy connection to players. Rather, the excellently presented fantasy world & tropes convey a kind of pre-Tolkein fiction, both celebrated & demystified. Out with the enigmatic solutions, in with the peeling skin of what Hydlide sought to achieve.

The final boss becoming a classic arcade shooter is a bit too cute, though. (Even considering Hydlide creator Tokihiro Naito's own penchant for STGs, this was too on-the-nose.) And the game can only immerse you so much into this primordial high fantasy structure without iterating on its mechanics the way Fairune 2 does. But I think Skipmore's original throwback ARPG is a panacea for any discussions revolving around Hydlide & its place in game design history. The original J-PC game made a critical leap from Druaga's coin-feeding gatekeeping to a more palatable, individualized experience you could still share with friends & other gamers. Fairune recaptures the novelty, strangeness, and sekaikan that Hydlide's fans felt in the mid-'80s, just for today's players.

Even if I much prefer the sequel for how it posits a world where Hydlide's sequels didn't overcomplicate themselves to ill end, there's every reason to replay the prequel. Do yourself a favor and try this out for size. It might have you thinking twice about laughing off proto-Zelda examples of the genre.

1974

ok 3 2 1 let's jam waggles to Cowboy Bebop as I light up the doobie and duel 'em

You have Kee Games to thank for gaming's original tank controls. I mean, it's in the name. But more than that, Steve Bristow's simpler take on the 1-on-1 vehicular combat of Spacewar! would end up saving Atari. Pong may have started that company's rise to fame, but the Pong market crash around the turn of 1974, plus the successful but loss-leading Gran Trak 10, put Bushnell & Dabney's venture on thin ice. The upstart, rockstar company that had made video games a fad almost met its demise, if not for the efforts of the affiliated company Bristow worked at.

Though technically a subsidiary of Atari, Kee Games had unique management and technical staff, such as experienced coin-op techie Bristow. They profited off of Pong clones while even Atari's originals couldn't, making waves in regions where Atari couldn't distribute. And then Tank happened. It quickly grew in popularity at trade shows and location tests, soon displacing the ailing Pong-likes that had flooded arcade and jukebox venues over the last year and a half. Atari's own Gran Trak 10, a revolution in arcade gaming, struggled to compete. What was so different this time?

Obviously this was and remains a very simple action game. You use two sticks to rotate or move back and forth, much like operating any construction or military treaded vehicle. But like Gran Trak, you weren't just shooting at the other player on an almost entirely black screen. The "course", or maze in Tank's case, let players strategize and tactically move towards and around each other. You could play mind games and take risky shots like never before, not even in then complex faire like Quadrapong. Just as fighting games today each have a meta, Bristow's game encouraged a similar kind of community learning and one-upmanship far beyond mere table tennis. The more complex controls didn't throw arcade-goers off—if anything, that added sense of realism or simulation made it more approachable.

In turn, Tank had finally achieved the "Spacewar! for the public" dream that Pitts & Tuck, Syzygy/Nutting, and then Atari had sought. Kee Games would sell more than a hundred thousand boards and cabinets through 1974 and beyond. Because Atari owned them with 90% company stock, this provided a financial and commercial boon. Tank and Gran Trak would, in tandem, prove that video games were more than a transient trend—coin-op businesses could expect these contraptions to improve, invent, and immerse their customers well beyond Pong.

Tank and its iterative sequels were so foundational for Atari & Kee Games that it would later influence their first multi-game cartridge console. The Atari VCS specifically borrows its iconic joystick design from a Tank II mini-console prototype, and an expanded port of Tank dubbed Combat was the main pack-in launch title alongside the system in 1977. While this may be as rudimentary as vehicular dueling has ever been, even compared to its space-borne predecessors, Tank's earned its place in arcade & video game history.

You have Kee Games to thank for gaming's original tank controls. I mean, it's in the name. But more than that, Steve Bristow's simpler take on the 1-on-1 vehicular combat of Spacewar! would end up saving Atari. Pong may have started that company's rise to fame, but the Pong market crash around the turn of 1974, plus the successful but loss-leading Gran Trak 10, put Bushnell & Dabney's venture on thin ice. The upstart, rockstar company that had made video games a fad almost met its demise, if not for the efforts of the affiliated company Bristow worked at.

Though technically a subsidiary of Atari, Kee Games had unique management and technical staff, such as experienced coin-op techie Bristow. They profited off of Pong clones while even Atari's originals couldn't, making waves in regions where Atari couldn't distribute. And then Tank happened. It quickly grew in popularity at trade shows and location tests, soon displacing the ailing Pong-likes that had flooded arcade and jukebox venues over the last year and a half. Atari's own Gran Trak 10, a revolution in arcade gaming, struggled to compete. What was so different this time?

Obviously this was and remains a very simple action game. You use two sticks to rotate or move back and forth, much like operating any construction or military treaded vehicle. But like Gran Trak, you weren't just shooting at the other player on an almost entirely black screen. The "course", or maze in Tank's case, let players strategize and tactically move towards and around each other. You could play mind games and take risky shots like never before, not even in then complex faire like Quadrapong. Just as fighting games today each have a meta, Bristow's game encouraged a similar kind of community learning and one-upmanship far beyond mere table tennis. The more complex controls didn't throw arcade-goers off—if anything, that added sense of realism or simulation made it more approachable.

In turn, Tank had finally achieved the "Spacewar! for the public" dream that Pitts & Tuck, Syzygy/Nutting, and then Atari had sought. Kee Games would sell more than a hundred thousand boards and cabinets through 1974 and beyond. Because Atari owned them with 90% company stock, this provided a financial and commercial boon. Tank and Gran Trak would, in tandem, prove that video games were more than a transient trend—coin-op businesses could expect these contraptions to improve, invent, and immerse their customers well beyond Pong.

Tank and its iterative sequels were so foundational for Atari & Kee Games that it would later influence their first multi-game cartridge console. The Atari VCS specifically borrows its iconic joystick design from a Tank II mini-console prototype, and an expanded port of Tank dubbed Combat was the main pack-in launch title alongside the system in 1977. While this may be as rudimentary as vehicular dueling has ever been, even compared to its space-borne predecessors, Tank's earned its place in arcade & video game history.

1993

It's no Shitty Shitty Bang Bang, but I'd prefer it be a well-designed puzzler than a mere funny PC-98 meme. Sex 2 ahem

Bit^2's 1993 train-crash avoidance simulator starts you off with an egghead of a railway operator asking you to manually operate their trains. Why? All the company's sensors & computers have gone haywire, and only you have the skills to run it all until it's fixed! Simple enough, just give me the master control panel and—oh, wait, I have to flip every little switch. Every train's gotta pick up their passengers or cargo, then make it safely to the exit. Someone's gonna owe me money after this job.

Chitty Chitty Train leaves you plenty compensated, thankfully. The game's mouse controls are smooth yet precise. Its audiovisuals are rock solid, from jaunty chiptune marches to the intricate pixel art. (Seriously, why doesn't this title get more attention from PC-X8 art rebloggers and art bots?! The eroge picks are getting old, fellas.) And just like you'd expect from a meticulous PC puzzler from this era a la Lemmings, each level offers plenty of challenge. Well-designed challenges, might I add.

We're far from Transport Tycoon and its descendants here, with nary an automatic timetable at hand. Think of it more like an arcade-y, non-sim distillation of A-Train's transit mechanics. All your train scheduling happens through manually clicking on switches, calculating how long different types of cars will travel the circuit you put them on. Quite a few early puzzles give you very limited headroom, stacking multiple moving engines across shared track they'll easily bash heads on. Planning your moves and switch timing is the meta, but a good amount of improvisation can help when least expected. It hardly feels like a train version of Sokoban, where you're so obviously restricted and can only realistically solve the puzzle in a given way.

Best of all, there's a map maker! Creating and sharing your levels via the game disk might have mattered more back in its heyday, but Chitty Chitty Train's such a small game in size that it's trivial now. You can try it out today via PC-98 emulators (hint: check a certain Archive), and I think any fans of old-school logic games will get plenty out of this very overlooked romp. Although the game's always had English menus, the recent fan patch does translate the opening if you're interested.

Bit^2's 1993 train-crash avoidance simulator starts you off with an egghead of a railway operator asking you to manually operate their trains. Why? All the company's sensors & computers have gone haywire, and only you have the skills to run it all until it's fixed! Simple enough, just give me the master control panel and—oh, wait, I have to flip every little switch. Every train's gotta pick up their passengers or cargo, then make it safely to the exit. Someone's gonna owe me money after this job.

Chitty Chitty Train leaves you plenty compensated, thankfully. The game's mouse controls are smooth yet precise. Its audiovisuals are rock solid, from jaunty chiptune marches to the intricate pixel art. (Seriously, why doesn't this title get more attention from PC-X8 art rebloggers and art bots?! The eroge picks are getting old, fellas.) And just like you'd expect from a meticulous PC puzzler from this era a la Lemmings, each level offers plenty of challenge. Well-designed challenges, might I add.

We're far from Transport Tycoon and its descendants here, with nary an automatic timetable at hand. Think of it more like an arcade-y, non-sim distillation of A-Train's transit mechanics. All your train scheduling happens through manually clicking on switches, calculating how long different types of cars will travel the circuit you put them on. Quite a few early puzzles give you very limited headroom, stacking multiple moving engines across shared track they'll easily bash heads on. Planning your moves and switch timing is the meta, but a good amount of improvisation can help when least expected. It hardly feels like a train version of Sokoban, where you're so obviously restricted and can only realistically solve the puzzle in a given way.

Best of all, there's a map maker! Creating and sharing your levels via the game disk might have mattered more back in its heyday, but Chitty Chitty Train's such a small game in size that it's trivial now. You can try it out today via PC-98 emulators (hint: check a certain Archive), and I think any fans of old-school logic games will get plenty out of this very overlooked romp. Although the game's always had English menus, the recent fan patch does translate the opening if you're interested.

1983

Green the putt. Ball the club. Falcom the Nihon. Meme the name.

Before Nintendo & HAL Laboratory codified the bare basics of home golf games—graphical aiming, multi-step power bar, you know the drill—experiments like this obscure Falcom release were the norm. They weren't alone: everyone from Atari to T&E Soft tried their hand at making either casual putt romps or hardcore simulations. Both consoles & micro-computers of the era were hard-pressed to make golf feel fun, even if they could simplify or complexify it. As a regular cassette game coded in BASIC, Computer the Golf always had humble aims, uninterested in changing trends.

I still managed to have a good time despite the archaic mechanics & presentation, however. Each hole's sensibly designed & placed to reflect growing expectations for player skill. Your club variety & multi-step power bar (yes, these existed before Nintendo's Golf!) also make precision shots easier to achieve. For 3500 yen, players would have gotten decent value, especially if you wanted something from Falcom with more of a puzzle feel. There's also the requisite scorecard feature, plus cursor key controls at a time when most PC-88 & FM-7 releases stuck with numpad keys.

The game's code credits Norihiko Yaku as programmer, and very likely the only creator involved. It's hard to remember a time when just one person could make a fully-featured home game, let alone at Falcom prior to their massive '80s successes. I appreciate the quaintness & low stakes of this pre-Xanadu, pre-Ys software you'd just find on the shelf in a bag, sitting next to all those Apple II imports that started the company. Soon you'd have naught but xRPGs & graphic adventures from the studio, all requiring more and more talented people to create. Sorcerian & Legacy of the Wizard make no mention of bourgeois sports; that's for the rest of bubble-era Japan to covet!

Maybe this will remain a footnote, but it's an inoffensive one. It's ultimately one of the best J-PC sports games for its era, right alongside T&E Soft's fully 3D efforts. Paradigm shifts would come with No. 1 Golf on Sharp X1, then Nintendo's Golf and competing pro golf series from Enix & Telenet. The times were a-changin'.

Before Nintendo & HAL Laboratory codified the bare basics of home golf games—graphical aiming, multi-step power bar, you know the drill—experiments like this obscure Falcom release were the norm. They weren't alone: everyone from Atari to T&E Soft tried their hand at making either casual putt romps or hardcore simulations. Both consoles & micro-computers of the era were hard-pressed to make golf feel fun, even if they could simplify or complexify it. As a regular cassette game coded in BASIC, Computer the Golf always had humble aims, uninterested in changing trends.

I still managed to have a good time despite the archaic mechanics & presentation, however. Each hole's sensibly designed & placed to reflect growing expectations for player skill. Your club variety & multi-step power bar (yes, these existed before Nintendo's Golf!) also make precision shots easier to achieve. For 3500 yen, players would have gotten decent value, especially if you wanted something from Falcom with more of a puzzle feel. There's also the requisite scorecard feature, plus cursor key controls at a time when most PC-88 & FM-7 releases stuck with numpad keys.

The game's code credits Norihiko Yaku as programmer, and very likely the only creator involved. It's hard to remember a time when just one person could make a fully-featured home game, let alone at Falcom prior to their massive '80s successes. I appreciate the quaintness & low stakes of this pre-Xanadu, pre-Ys software you'd just find on the shelf in a bag, sitting next to all those Apple II imports that started the company. Soon you'd have naught but xRPGs & graphic adventures from the studio, all requiring more and more talented people to create. Sorcerian & Legacy of the Wizard make no mention of bourgeois sports; that's for the rest of bubble-era Japan to covet!

Maybe this will remain a footnote, but it's an inoffensive one. It's ultimately one of the best J-PC sports games for its era, right alongside T&E Soft's fully 3D efforts. Paradigm shifts would come with No. 1 Golf on Sharp X1, then Nintendo's Golf and competing pro golf series from Enix & Telenet. The times were a-changin'.

1978

And we can try, to understand,

The Atari games' effect on Nam[co]

Whether you're a plumber or a cute dungeon crawler, you're indebted to Nam, you're indebted to Nam. But it's not alright—it's not even okay. And I can't look the other way. Toru Iwatani's first game shows all the growing pains & missteps you'd expect from an arcade developer dabbling in microchip games after years of electromechanical (eremeka) products. It's more than a curio, though. The beginnings of Pac-Man's cheeky fun show up even this early, if you can believe it. Just know it's not the real deal—the Hee Bee Gee Bees, if you will.

Speaking later in his career, an Iwatani then swamped with management duties asserted that "making video games is an act of kindness to others, a tangible gift of happiness." This axiom of purpose comes after his own complaints about the stagnation of '80s game centers, then flush with shoot-em-ups and less-than-innovative software. Around 1987, even Namco's own arcade output had trailed off in mechanical ambition, trading out the derring-do of Dragon Buster for the excellent but conventional Dragon Spirit. One could argue he had rose-tinted glasses this early, ignoring all the clones and production frenzy of Golden Age arcade games like his own. But he's arguing most for elegance and player-first design, something attempted with Gee Bee.

Conceived as a compromise between the pinball tables he wanted to make and Pres. Nakamura & co.'s interest in imports like Breakout, their 1978 debut had ambitions. It's an early go at combining multiple mechanics and score strategies found in Steve Wozniak's creation and post-war pinball designs. Anyone walking by the cab would see the vague, amusing outline of a human face made from barriers & breakables. Together with the requisite comical marquee & paddle, this would have seemed familiar enough to players at the time while enticing them with novelty. What's the bee chipping away at? Are we stinging our selves with delight as the blocks dissipate, our attacks moving faster and faster? That kind of imagination springs forth from even a premise as simple as this.

I'm sad to say that the mind-meld of pinball and electronic squash just wasn't feasible this early on. Gee Bee offers neither the flash and nuances of the best flipper games Chicago could offer, nor the pure and addictive game loop Wozniak wrought from Clean Sweep. Iwatani and his co-developers hamstrung themselves by refusing to commit one way or the other. There's a few too many ways to screw yourself over in Gee Bee, from less intuitive physics to the screen resetting every time you lose a ball. Inability to reach high scores is one thing, but that denial of progress is a buzzkill. All your careful threading of the needle to hit all the NAMCO letters for the multiplier can go to waste in an instant. All the patience needed to clear one upper half, thus blocking the ball from a previously open tunnel, feels like a cruel joke.

If what I'm saying gives you the heebie-jeebies, then don't overthink it. The game's recognizable to modern players, and fun for a little bit at least. But there's just no longevity here except for ardent score seekers. I can see why, for all of Namco's work to promote it, Gee Bee didn't take off at home or abroad. Space Invaders had innovated upon the destructive form of Pong that Breakout started, while this feels like an evolutionary dead-end. Bomb Bee & Cutie Q would try to salvage this with some success, of course. I'm just unsurprised that Iwatani learned from the mistakes made here, keeping that focus on levity & eclectic design in Pac-Man & Libble Rabble. On a technical level, this board still has some positives of note, mainly its fluidity & amount of color vs. the rest of the market. It's worth a try for historic value, and a sneak peek of the game development ethos Iwatani spread to other Namco notables in the coming years.

The Atari games' effect on Nam[co]

Whether you're a plumber or a cute dungeon crawler, you're indebted to Nam, you're indebted to Nam. But it's not alright—it's not even okay. And I can't look the other way. Toru Iwatani's first game shows all the growing pains & missteps you'd expect from an arcade developer dabbling in microchip games after years of electromechanical (eremeka) products. It's more than a curio, though. The beginnings of Pac-Man's cheeky fun show up even this early, if you can believe it. Just know it's not the real deal—the Hee Bee Gee Bees, if you will.

Speaking later in his career, an Iwatani then swamped with management duties asserted that "making video games is an act of kindness to others, a tangible gift of happiness." This axiom of purpose comes after his own complaints about the stagnation of '80s game centers, then flush with shoot-em-ups and less-than-innovative software. Around 1987, even Namco's own arcade output had trailed off in mechanical ambition, trading out the derring-do of Dragon Buster for the excellent but conventional Dragon Spirit. One could argue he had rose-tinted glasses this early, ignoring all the clones and production frenzy of Golden Age arcade games like his own. But he's arguing most for elegance and player-first design, something attempted with Gee Bee.

Conceived as a compromise between the pinball tables he wanted to make and Pres. Nakamura & co.'s interest in imports like Breakout, their 1978 debut had ambitions. It's an early go at combining multiple mechanics and score strategies found in Steve Wozniak's creation and post-war pinball designs. Anyone walking by the cab would see the vague, amusing outline of a human face made from barriers & breakables. Together with the requisite comical marquee & paddle, this would have seemed familiar enough to players at the time while enticing them with novelty. What's the bee chipping away at? Are we stinging our selves with delight as the blocks dissipate, our attacks moving faster and faster? That kind of imagination springs forth from even a premise as simple as this.

I'm sad to say that the mind-meld of pinball and electronic squash just wasn't feasible this early on. Gee Bee offers neither the flash and nuances of the best flipper games Chicago could offer, nor the pure and addictive game loop Wozniak wrought from Clean Sweep. Iwatani and his co-developers hamstrung themselves by refusing to commit one way or the other. There's a few too many ways to screw yourself over in Gee Bee, from less intuitive physics to the screen resetting every time you lose a ball. Inability to reach high scores is one thing, but that denial of progress is a buzzkill. All your careful threading of the needle to hit all the NAMCO letters for the multiplier can go to waste in an instant. All the patience needed to clear one upper half, thus blocking the ball from a previously open tunnel, feels like a cruel joke.

If what I'm saying gives you the heebie-jeebies, then don't overthink it. The game's recognizable to modern players, and fun for a little bit at least. But there's just no longevity here except for ardent score seekers. I can see why, for all of Namco's work to promote it, Gee Bee didn't take off at home or abroad. Space Invaders had innovated upon the destructive form of Pong that Breakout started, while this feels like an evolutionary dead-end. Bomb Bee & Cutie Q would try to salvage this with some success, of course. I'm just unsurprised that Iwatani learned from the mistakes made here, keeping that focus on levity & eclectic design in Pac-Man & Libble Rabble. On a technical level, this board still has some positives of note, mainly its fluidity & amount of color vs. the rest of the market. It's worth a try for historic value, and a sneak peek of the game development ethos Iwatani spread to other Namco notables in the coming years.

1982

So it goes, the repeating blunders of pi(lots). I can't help but laugh every time I hit the green & go boom, knowing it's as much a technical choice as absurd design. Believability aside, it's nice to face consequences for mismanaging your velocity & inertia. Just dodging the targets and naught else would get dull, an adjective I simply can't slap on River Raid.

Carol Shaw knew a good role model when she saw one. Konami's Scramble isn't quite as well-recognized today for the precedents it set, both for arcade shooters & genres beyond. Yet she was quick to adapt that game's scrolling, segmented yet connected world into something the VCS could handle. Making any equivalent of a tiered power-up system was out of the question, but River Raid compensates with its little touches. The skill progression in this title really sneaks up on you, much to my delight.

Acceleration, deceleration, & yanking that yoke—combine that with fuel management, plus the scoring rubric, and it's a lot more to absorb than normal for a VCS shooter. I made it to 50k points before feeling sated, having cleared maybe a couple tens of stages (neatly separated by the bridges you demolish), and I could go for seconds. Maybe some extra time & finesse could have added more of a soundscape here, albeit limited by the POKEY like usual. But there's a completeness, the beginnings of verisimilitude in this genre which you only saw inklings of before on consoles. Scramble's paradigm had come to the Atari.

Shaw's coding smarts are all over this, too. From pseudo-random endless shooting, to the play area using mirrored sections to minimize flickering, River Raid pushes its technical tier even beyond the smooth vertical scrolling. Going from 3D Tic-Tac-Toe to this must have felt triumphant. Her later works for Activision across Intellivision & succeeding Atari consoles carry on the pedigree made clear here. Worry not over fears of River Raid's reputation being outdated or unearned, reader. It's a worthy highlight of the 2600 library which I could fire up anytime in any mood.

Carol Shaw knew a good role model when she saw one. Konami's Scramble isn't quite as well-recognized today for the precedents it set, both for arcade shooters & genres beyond. Yet she was quick to adapt that game's scrolling, segmented yet connected world into something the VCS could handle. Making any equivalent of a tiered power-up system was out of the question, but River Raid compensates with its little touches. The skill progression in this title really sneaks up on you, much to my delight.

Acceleration, deceleration, & yanking that yoke—combine that with fuel management, plus the scoring rubric, and it's a lot more to absorb than normal for a VCS shooter. I made it to 50k points before feeling sated, having cleared maybe a couple tens of stages (neatly separated by the bridges you demolish), and I could go for seconds. Maybe some extra time & finesse could have added more of a soundscape here, albeit limited by the POKEY like usual. But there's a completeness, the beginnings of verisimilitude in this genre which you only saw inklings of before on consoles. Scramble's paradigm had come to the Atari.

Shaw's coding smarts are all over this, too. From pseudo-random endless shooting, to the play area using mirrored sections to minimize flickering, River Raid pushes its technical tier even beyond the smooth vertical scrolling. Going from 3D Tic-Tac-Toe to this must have felt triumphant. Her later works for Activision across Intellivision & succeeding Atari consoles carry on the pedigree made clear here. Worry not over fears of River Raid's reputation being outdated or unearned, reader. It's a worthy highlight of the 2600 library which I could fire up anytime in any mood.

2011

More like a last resort, but hey, gotta use those air miles.

Wuhu Island seems like a downgrade from the charcuterie board that is Pilotwings 64's islands. You're forever going to squint into the twilight while riding thermals, or futzing around behind the volcano in a jetpack thinking "I could be in Little States right now, sneaking into airplane garages for shits 'n' giggles." Thankfully there's still a rock-solid game here, building off PW64's knack for mission design and controls.

Pretty much every vehicle feels as good here, if not better, from the training plane to the pedal glider. (I'm a big fan of the latter, a beefed-up hang glider with more room for error and skillful control). Knocking out the early challenges to organically unlock the second-tier ride types is as fun as you'd hope for. And to their credit, Monster Games understands how to subtly haul you around the island between missions, switching up the scale & sightlines of your aerial trip with ease.

I still think the minigames, fun as they are, aren't anywhere near good as the original game's attack 'copter mission, nor the cannon & hopper you could abuse in PW64. The squirrel suit seems very underutilized for all you could do with it; no "dive through portals!" mission sticks in my mind. And the free-flight mode takes one step forward with collecting the hints, but a gorillion steps back via that time limit. Did they just not understand the appeal of traveling the world in PW64's Birdman suit, or were they just too self-conscious about only having one island to work with?

Except they have the golf island, which also goes relatively ignored aside from the fight against Meca Hawk. Bringing that big 'ol box of bolts back was awesome and hilarious (a set of missions involving it would have been even better). Truth be told, it's only the clever reuse of such limited content in Pilotwings Resort that earns it that last half-star. I love the polished game loop, replaying missions for better ranks, etc. But you'd think Nintendo would have afforded Monster Games a few more months to add more, at least in terms of modes, mission variations, and an unlockable Birdman.

As the last Pilotwings we might ever see, given the corp's disinterest in the franchise, it's a nice stopping point for sure. I'm perhaps a bit biased as this was my early-adopted 3DS exclusive of choice, but it's very much worth a visit to Wuhu on these wings of music if you get the chance. (Or, you know, cross the high seas to reach the island.) At least you'll have some outright jammin' funk & fusion hitting your ears, and an excellent implementation of 3D back when it seemed like just a novelty.

Anyway, either I'm going to end up finding some new indie take on the Pilotwings concept or it's high time someone like me makes a fully-fledged revival of it.

Wuhu Island seems like a downgrade from the charcuterie board that is Pilotwings 64's islands. You're forever going to squint into the twilight while riding thermals, or futzing around behind the volcano in a jetpack thinking "I could be in Little States right now, sneaking into airplane garages for shits 'n' giggles." Thankfully there's still a rock-solid game here, building off PW64's knack for mission design and controls.

Pretty much every vehicle feels as good here, if not better, from the training plane to the pedal glider. (I'm a big fan of the latter, a beefed-up hang glider with more room for error and skillful control). Knocking out the early challenges to organically unlock the second-tier ride types is as fun as you'd hope for. And to their credit, Monster Games understands how to subtly haul you around the island between missions, switching up the scale & sightlines of your aerial trip with ease.

I still think the minigames, fun as they are, aren't anywhere near good as the original game's attack 'copter mission, nor the cannon & hopper you could abuse in PW64. The squirrel suit seems very underutilized for all you could do with it; no "dive through portals!" mission sticks in my mind. And the free-flight mode takes one step forward with collecting the hints, but a gorillion steps back via that time limit. Did they just not understand the appeal of traveling the world in PW64's Birdman suit, or were they just too self-conscious about only having one island to work with?

Except they have the golf island, which also goes relatively ignored aside from the fight against Meca Hawk. Bringing that big 'ol box of bolts back was awesome and hilarious (a set of missions involving it would have been even better). Truth be told, it's only the clever reuse of such limited content in Pilotwings Resort that earns it that last half-star. I love the polished game loop, replaying missions for better ranks, etc. But you'd think Nintendo would have afforded Monster Games a few more months to add more, at least in terms of modes, mission variations, and an unlockable Birdman.

As the last Pilotwings we might ever see, given the corp's disinterest in the franchise, it's a nice stopping point for sure. I'm perhaps a bit biased as this was my early-adopted 3DS exclusive of choice, but it's very much worth a visit to Wuhu on these wings of music if you get the chance. (Or, you know, cross the high seas to reach the island.) At least you'll have some outright jammin' funk & fusion hitting your ears, and an excellent implementation of 3D back when it seemed like just a novelty.

Anyway, either I'm going to end up finding some new indie take on the Pilotwings concept or it's high time someone like me makes a fully-fledged revival of it.

Cold take, but Infogrames really was poison for just about every company & brand it amoeba-ed. Ocean, GT Interactive, Humungous Entertainment...even old ailing Atari (properties, not its people) via the Hasbro Entertainment buyout. All got wrapped up into a top-heavy, mismanaged juggernaut that eventually fell to pieces, only rebuilding well into their Atari SA rebrand.

Atari Anniversary Edition isn't too interesting on its own. The 12 games included were harder to access back then, sure, but the DIY arcade revival & emulation scenes have obviated the issue. (Hence why Atari 50 is so commendable, going well beyond just the usual roster by adding "what if"-style games and supplements galore.) Emulation quality's alright, and it certainly seems playable on every platform it reached. I can think of worse compilations to spend an evening with.

What strikes me, though, is the "anniversary" bit. Anniversary of what, exactly? Centipede? Tempest? Asteroids Deluxe? Those three share equal billing with the other nine, though. Infogrames' idea of matching a lightweight arcade compilation with this much pomp and circumstance is hilarious. No doubt the team at Digital Eclipse liked the paycheck, but who did they think the rainbow armadillo was fooling? My dad, I suppose. It's the one Dreamcast game he played much, and thankfully our local barcade can slake that thirst.

It's a shame that Digital Eclipse didn't get more of a chance to do here what they can now. I suppose that's just corporate reality and the publisher shooting for a quick buck, value be damned. Even DE's earlier PS1 Atari collection had a bonus documentary unlike this. Dark days. All this makes it easier to appreciate the old game compilations we get today, inching closer and closer to the style of box-set release you get from Criterion, Arrow, and other boutique film shops. Let's hope things continue to improve—that curated redistribution of notable classics can further unshackle from the fetters of simple nostalgia.

Atari Anniversary Edition isn't too interesting on its own. The 12 games included were harder to access back then, sure, but the DIY arcade revival & emulation scenes have obviated the issue. (Hence why Atari 50 is so commendable, going well beyond just the usual roster by adding "what if"-style games and supplements galore.) Emulation quality's alright, and it certainly seems playable on every platform it reached. I can think of worse compilations to spend an evening with.

What strikes me, though, is the "anniversary" bit. Anniversary of what, exactly? Centipede? Tempest? Asteroids Deluxe? Those three share equal billing with the other nine, though. Infogrames' idea of matching a lightweight arcade compilation with this much pomp and circumstance is hilarious. No doubt the team at Digital Eclipse liked the paycheck, but who did they think the rainbow armadillo was fooling? My dad, I suppose. It's the one Dreamcast game he played much, and thankfully our local barcade can slake that thirst.

It's a shame that Digital Eclipse didn't get more of a chance to do here what they can now. I suppose that's just corporate reality and the publisher shooting for a quick buck, value be damned. Even DE's earlier PS1 Atari collection had a bonus documentary unlike this. Dark days. All this makes it easier to appreciate the old game compilations we get today, inching closer and closer to the style of box-set release you get from Criterion, Arrow, and other boutique film shops. Let's hope things continue to improve—that curated redistribution of notable classics can further unshackle from the fetters of simple nostalgia.

1974

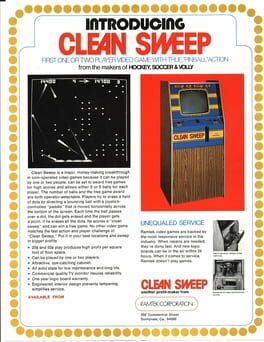

Maybe you've seen the term "TTL" thrown about before, mainly for foundational 1970s arcade games. These pre-integrated circuit boards imposed many limits on creators, from Al Alcorn's team making Pong in '72 to SEGA sending the format off with their impressive racer Monaco GP. But in the years before large-scale ICs became feasible for mass-produced games, why not just stack a bunch of transistors next to each other for old times' sake?

Clean Sweep isn't much of a game beyond its historic significance. The idea of single-player Pong, without a computer to play against, must have seemed absurd back then. Of coursed, the solution was simple: fill the screen with other balls to collect. You work to deprive the play area of its starting flourish, bringing back Pong's negative space as you go. Now the opponent is yourself, both an enabler of on-screen events and the disabler should you fail to reflect projectiles. This makes for a fun experience at first, at least until repetition & self-consciousness set in.

So here's the question: why exactly did this disappear into the annals of '70s game lore while Breakout, its clear descendant, ascended to the pantheon? There's many good answers. Atari had production & distribution leverage outmatching even mighty Ramtek, best known then for their Baseball game. Woz & Jobs' design simply had better physics and kinaesthetics, from the tetchy ball-paddle inertia to the simple pleasures of trapping a ball above the wall, watching it go to work. Most likely, the '76 game just had better timing. Pong clone frenzy was the order of the day in Clean Sweep's time, with Atari's own new products struggling to keep up. Something with more of an identity like Ramtek Baseball would have done better than another space game, or what seemed to the public like a weirder take on solo Pong.

(I find it funny how the other review currently claims Clean Sweep is the clone despite predating Breakout. One could boil either game down to "single-player Pong clone" if they really try. That's a kind of reductive take I try to avoid when possible, even when discussing something this rudimentary.)

If you're intrigued by any of this, download DICE and find a copy of Clean Sweep & other TTL games (like the original Breakout, of course!). I can't think of any arcades that might still own, operate, & maintain this relic today other than Galloping Ghost up near Chicago, sadly. And it's nowhere on modern retro collections for obvious emulation-related reasons. But it paved the way for one of the most significant '70s games, and isn't half-bad to play for a few minutes either.

Clean Sweep isn't much of a game beyond its historic significance. The idea of single-player Pong, without a computer to play against, must have seemed absurd back then. Of coursed, the solution was simple: fill the screen with other balls to collect. You work to deprive the play area of its starting flourish, bringing back Pong's negative space as you go. Now the opponent is yourself, both an enabler of on-screen events and the disabler should you fail to reflect projectiles. This makes for a fun experience at first, at least until repetition & self-consciousness set in.

So here's the question: why exactly did this disappear into the annals of '70s game lore while Breakout, its clear descendant, ascended to the pantheon? There's many good answers. Atari had production & distribution leverage outmatching even mighty Ramtek, best known then for their Baseball game. Woz & Jobs' design simply had better physics and kinaesthetics, from the tetchy ball-paddle inertia to the simple pleasures of trapping a ball above the wall, watching it go to work. Most likely, the '76 game just had better timing. Pong clone frenzy was the order of the day in Clean Sweep's time, with Atari's own new products struggling to keep up. Something with more of an identity like Ramtek Baseball would have done better than another space game, or what seemed to the public like a weirder take on solo Pong.

(I find it funny how the other review currently claims Clean Sweep is the clone despite predating Breakout. One could boil either game down to "single-player Pong clone" if they really try. That's a kind of reductive take I try to avoid when possible, even when discussing something this rudimentary.)

If you're intrigued by any of this, download DICE and find a copy of Clean Sweep & other TTL games (like the original Breakout, of course!). I can't think of any arcades that might still own, operate, & maintain this relic today other than Galloping Ghost up near Chicago, sadly. And it's nowhere on modern retro collections for obvious emulation-related reasons. But it paved the way for one of the most significant '70s games, and isn't half-bad to play for a few minutes either.

1991

Remember when games started with saucy sorceresses blasting both of your pauldron-wearing badasses down into the cursed underworld? Pepperidge Farm remembers.

Nihon Falcom already had a history of making some of the best dungeon-crawling odysseys a Japanese PC player could buy. Brandish kept that legacy relevant, and then some. Modern players can laugh at the snappy, initially jarring over-the-shoulder camera, or wonder where the hell they're going in the game's early labyrinths. But I love how this game rewards an unction of patience, a mentality of adapt or die befitting the premise. What would you do if you were Ares Toraernos, decorated mercenary now marooned in the depths of a fallen kingdom? How would you worm your way out of this hell, beleaguered by monsters, deathtraps, and mysteries on all sides? We peer down into this man's trials by fire, yet are thrown to and thro as he methodically rounds corners into one gauntlet after another. To say nothing of his unwanted nemesis Dela Delon, the aforementioned magical minimally clothed madame hunting you down! This wouldn't be the last time Ares—and you, his far-off companion—has to face the bowels of madness and come out intact.

Speaking of jarring, that camera. It's definitely something you can get used to, unless it gives you genuine motion sickness. (Dramamine works for that…unless you're allergic, in which case I understand.) Swapping between mouse and keyboard controls, something new for a Falcom title of this vintage, also asks for some dexterity. But I don't consider this the kind of filter that you can find in more demanding ARPGs like Sekiro or Ninja Gaiden Black. Getting to grips with Brandish asks for a mix of tenacity, analysis, and maybe a few false starts. It's a breezy play, coming in around 8 to 12 hours, give or take. Replays are even encouraged by the game's own ending sequence, which summarizes your playtime and related stats before awarding a ranking. This system would later pop up in Falcom's own Xanadu Next, a boon sign if any.

Should you try Brandish out for size and the split-second camera snaps throws you off, don't panic! Getting used to it took me some time, and yet it paid off so well. I almost want to pity folks like SNESDrunk who, having played the SNES conversion, wrote this game off entirely because of this aspect. Keep an eye on the map and your compass to reorient when needed—even better if the version you're playing has both on-screen at all times.

I'll let you in on a secret: you should be playing the PC-98 version. Or the PSP remake, if experiencing the minimal albeit charming story matters to you. Yes, only the SNES port was ever localized, but I'd take the PC original over it any day. The awkwardness of the console version stems mainly from its reduced HUD and lack of mouse controls. Brandish's lead developers, first Yoshio Kiya (of Xanadu fame) and then Yukio Takahashi, wanted to move Falcom's game designs beyond simple keyboard or joystick schemes. While both Dinosaur and Popful Mail started off Falcom's 1990s stretch with PC-88 era controls, Brandish & its cousin Lord Monarch would explicitly target mouse users, keeping keyboard as an alternative. I tend to use both options, with keys for strafing and mouse to switch between interactions.

Brandish has you crawling through several multi-floor dungeons, each increasingly challenging and claustrophobic through a variety of means. Like the older, arguably more brutal CRPGs Kiya & co. had made, you have limited resources to work with, from deteriorating weapons to a set number of loot chests per level. One thing you'll always have is a chance to rest—if you aren't maybe fatally interrupted, that is. Resting works here much like in classic Rogue-likes, with harsh consequences should a monster attack you as you sleep. But it's your main way to recover health & mana, and an incentive to learn each part of every dungeon. Finding one-way tunnels with doors is a blessing, and managing your limited-space inventory comes naturally. I think Brandish often feels harder than it is; being able to rest & save progress anywhere plays into this. We're years ahead of actually brutal classics like 1985's Xanadu, or even something contemporary like SEGA's Fatal Labyrinth.

Character advancement is also just as interesting here as in Kiya's earlier works. You have to balance between growing physical and magical strength, as well as health, via how you fight enemies. It's very elegant: striking and killing with weapons raises the former, and doing it with spell scrolls helps the latter. This maps almost dead-on to Xanadu's physical-magical dichotomy, just without that game's emphasis on leveling individual weapon experience. Here you can easily switch between armaments, choosing which mix of speed, power, and animation frames works best. Fire and cure spells come quickly, too, enriching your action economy as early as the Vittorian Ruins. By the time I get to truly challenging areas like the Dark Zone, I've maxed out my stats and can only hope to find better gear for my travails. This brings in a bit of that Ys I feeling, where you know only your skills and wisdom can get you through this struggle, not just grinding.

Wisdom is something the people who built these tunnels clearly lacked. The old king of Vittoria, having plunged him and his people into this condemned netherland, had done a fine job setting up spiky pits, poisonous wells, mechanical log rams…the works! Much of Brandish's joy comes from solving all these navigation micro-puzzles while keeping distance from wandering foes. It's hard to fall out of the game's quick "one more floor!" flow. You're never truly alone, either. Shopkeepers occasionally pop up throughout most dungeons, offering both supplies and musings on their lives and the surrounding lore. A certain woman warlock loves to show up and taunt you, only to get bamboozled by the same hazards you've faced (or are about to!). It may be a crunchy 1990 action-RPG with all the aged aspects that entails, but I'd never accuse Brandish of being lifeless. The sequels would only improve in this sense, adding more and more NPCs and story without ever sacrificing that essential oppressive atmosphere and isolation.

Nothing's quite as gratifying as reaching the king's Fortress, packing more heat than a whole army of knights, fearing not so much the bestiary as you do the conundrums. Why is everything so damn fleshy here? How are these pillars moving around the room in such a bizarre way? Will I have to tango with invisible enemies again, or golems awakening around me as I open a suspicious chest? And where am I going anyway?! Brandish avoids the potential worsts of these questions by equipping you with one of gaming history's best mapping systems. Predating the likes of Etrian Odyssey by more than a decade, the game's minimap demonstrates why this game would always have a tough time converting to console play. This precise mouse-based minimap, with multiple swatches you can use to mark map items & boundaries, is itself quite fun to tinker with. Later games would challenge your map-making skills further, going as far as adding enemies that passively destroy your map over time and space! That's not an issue in this first game, thankfully. Falcom's maybe a bit too nice in that regard.

For that matter, I can't shake the feeling that Falcom, still reeling from their turn-of-the-'90s staff exodus (to new studios like Ancient and Quintet), held back on Brandish's ambitions. Popful Mail shares something of a similar fate: these are two wonderfully made adventures, no doubt, but also compromise in key areas. For the former, difficulty balance and repetition can set in later on. For Ares' first expedition into darkness, it's more so the developer's restraint in making truly complex dungeons. I just wish the complexity of both puzzles and combat areas ramped up quicker here, something the rest of the series fixes. Sure, a lot of folks might get stumped at the3 and 5 floor tiles puzzle in Tower, but there's maybe a couple headscratchers here at best. Likewise, combat's sometimes trivialized by the ease of jumping over and away from foes, many of which lack ranged attacks. I can forgive all of this since the rest is just so good, but the creative compromises I've noticed on replays mean I can't really rate this higher. (Brandish 2, incidentally, gets an extra half star for its ambitions despite introducing some more jank of its own.)

Kudos to the boss designs though, especially later on. I'm especially fond of the Black Widow, Lobster, and final boss fights for how they make use your available space to the maximum. Yes, you fight a gigantic lobster towards the end. Brandish sort of gets the Giant Enemy Crab stamp of approval.

All that said, the original Brandish was as awesome & appropriate a successor to Xanadu's legacy as Falcom fans could have hoped for. Hell, it even reminds me of the best parts from Sorcerian and Drasle Family (aka Legacy of the Wizard). Rare is it that an ARPG this old still feels relevant to modern play-styles, from Souls-style character building to the simple but effective itch.io puzzlers made today. It's telling how only Falcom could effectively bring this series to consoles, despite Koei arguably having more resources at the time for their SNES ports. Kiya, Takahashi, and others soon working on this series would iterate on the rock-solid foundation set here. The real downer is how quickly folks turn away from the series itself because it's either funnier or more convenient to crap on the third-first-person perspective. Few ARPG-dungeon crawler hybrids are as consistent, engrossing, and replayable as this.

The studio's largely moved on to more profitable pastures, with Ys and Trails being such huge tentpole series sucking up their time and resources. My kingdom for even a simple port of Brandish: The Dark Revenant to modern platforms! And my heart to those who give this series a chance.

Nihon Falcom already had a history of making some of the best dungeon-crawling odysseys a Japanese PC player could buy. Brandish kept that legacy relevant, and then some. Modern players can laugh at the snappy, initially jarring over-the-shoulder camera, or wonder where the hell they're going in the game's early labyrinths. But I love how this game rewards an unction of patience, a mentality of adapt or die befitting the premise. What would you do if you were Ares Toraernos, decorated mercenary now marooned in the depths of a fallen kingdom? How would you worm your way out of this hell, beleaguered by monsters, deathtraps, and mysteries on all sides? We peer down into this man's trials by fire, yet are thrown to and thro as he methodically rounds corners into one gauntlet after another. To say nothing of his unwanted nemesis Dela Delon, the aforementioned magical minimally clothed madame hunting you down! This wouldn't be the last time Ares—and you, his far-off companion—has to face the bowels of madness and come out intact.

Speaking of jarring, that camera. It's definitely something you can get used to, unless it gives you genuine motion sickness. (Dramamine works for that…unless you're allergic, in which case I understand.) Swapping between mouse and keyboard controls, something new for a Falcom title of this vintage, also asks for some dexterity. But I don't consider this the kind of filter that you can find in more demanding ARPGs like Sekiro or Ninja Gaiden Black. Getting to grips with Brandish asks for a mix of tenacity, analysis, and maybe a few false starts. It's a breezy play, coming in around 8 to 12 hours, give or take. Replays are even encouraged by the game's own ending sequence, which summarizes your playtime and related stats before awarding a ranking. This system would later pop up in Falcom's own Xanadu Next, a boon sign if any.

Should you try Brandish out for size and the split-second camera snaps throws you off, don't panic! Getting used to it took me some time, and yet it paid off so well. I almost want to pity folks like SNESDrunk who, having played the SNES conversion, wrote this game off entirely because of this aspect. Keep an eye on the map and your compass to reorient when needed—even better if the version you're playing has both on-screen at all times.

I'll let you in on a secret: you should be playing the PC-98 version. Or the PSP remake, if experiencing the minimal albeit charming story matters to you. Yes, only the SNES port was ever localized, but I'd take the PC original over it any day. The awkwardness of the console version stems mainly from its reduced HUD and lack of mouse controls. Brandish's lead developers, first Yoshio Kiya (of Xanadu fame) and then Yukio Takahashi, wanted to move Falcom's game designs beyond simple keyboard or joystick schemes. While both Dinosaur and Popful Mail started off Falcom's 1990s stretch with PC-88 era controls, Brandish & its cousin Lord Monarch would explicitly target mouse users, keeping keyboard as an alternative. I tend to use both options, with keys for strafing and mouse to switch between interactions.

Brandish has you crawling through several multi-floor dungeons, each increasingly challenging and claustrophobic through a variety of means. Like the older, arguably more brutal CRPGs Kiya & co. had made, you have limited resources to work with, from deteriorating weapons to a set number of loot chests per level. One thing you'll always have is a chance to rest—if you aren't maybe fatally interrupted, that is. Resting works here much like in classic Rogue-likes, with harsh consequences should a monster attack you as you sleep. But it's your main way to recover health & mana, and an incentive to learn each part of every dungeon. Finding one-way tunnels with doors is a blessing, and managing your limited-space inventory comes naturally. I think Brandish often feels harder than it is; being able to rest & save progress anywhere plays into this. We're years ahead of actually brutal classics like 1985's Xanadu, or even something contemporary like SEGA's Fatal Labyrinth.

Character advancement is also just as interesting here as in Kiya's earlier works. You have to balance between growing physical and magical strength, as well as health, via how you fight enemies. It's very elegant: striking and killing with weapons raises the former, and doing it with spell scrolls helps the latter. This maps almost dead-on to Xanadu's physical-magical dichotomy, just without that game's emphasis on leveling individual weapon experience. Here you can easily switch between armaments, choosing which mix of speed, power, and animation frames works best. Fire and cure spells come quickly, too, enriching your action economy as early as the Vittorian Ruins. By the time I get to truly challenging areas like the Dark Zone, I've maxed out my stats and can only hope to find better gear for my travails. This brings in a bit of that Ys I feeling, where you know only your skills and wisdom can get you through this struggle, not just grinding.

Wisdom is something the people who built these tunnels clearly lacked. The old king of Vittoria, having plunged him and his people into this condemned netherland, had done a fine job setting up spiky pits, poisonous wells, mechanical log rams…the works! Much of Brandish's joy comes from solving all these navigation micro-puzzles while keeping distance from wandering foes. It's hard to fall out of the game's quick "one more floor!" flow. You're never truly alone, either. Shopkeepers occasionally pop up throughout most dungeons, offering both supplies and musings on their lives and the surrounding lore. A certain woman warlock loves to show up and taunt you, only to get bamboozled by the same hazards you've faced (or are about to!). It may be a crunchy 1990 action-RPG with all the aged aspects that entails, but I'd never accuse Brandish of being lifeless. The sequels would only improve in this sense, adding more and more NPCs and story without ever sacrificing that essential oppressive atmosphere and isolation.

Nothing's quite as gratifying as reaching the king's Fortress, packing more heat than a whole army of knights, fearing not so much the bestiary as you do the conundrums. Why is everything so damn fleshy here? How are these pillars moving around the room in such a bizarre way? Will I have to tango with invisible enemies again, or golems awakening around me as I open a suspicious chest? And where am I going anyway?! Brandish avoids the potential worsts of these questions by equipping you with one of gaming history's best mapping systems. Predating the likes of Etrian Odyssey by more than a decade, the game's minimap demonstrates why this game would always have a tough time converting to console play. This precise mouse-based minimap, with multiple swatches you can use to mark map items & boundaries, is itself quite fun to tinker with. Later games would challenge your map-making skills further, going as far as adding enemies that passively destroy your map over time and space! That's not an issue in this first game, thankfully. Falcom's maybe a bit too nice in that regard.

For that matter, I can't shake the feeling that Falcom, still reeling from their turn-of-the-'90s staff exodus (to new studios like Ancient and Quintet), held back on Brandish's ambitions. Popful Mail shares something of a similar fate: these are two wonderfully made adventures, no doubt, but also compromise in key areas. For the former, difficulty balance and repetition can set in later on. For Ares' first expedition into darkness, it's more so the developer's restraint in making truly complex dungeons. I just wish the complexity of both puzzles and combat areas ramped up quicker here, something the rest of the series fixes. Sure, a lot of folks might get stumped at the

Kudos to the boss designs though, especially later on. I'm especially fond of the Black Widow, Lobster, and final boss fights for how they make use your available space to the maximum. Yes, you fight a gigantic lobster towards the end. Brandish sort of gets the Giant Enemy Crab stamp of approval.

All that said, the original Brandish was as awesome & appropriate a successor to Xanadu's legacy as Falcom fans could have hoped for. Hell, it even reminds me of the best parts from Sorcerian and Drasle Family (aka Legacy of the Wizard). Rare is it that an ARPG this old still feels relevant to modern play-styles, from Souls-style character building to the simple but effective itch.io puzzlers made today. It's telling how only Falcom could effectively bring this series to consoles, despite Koei arguably having more resources at the time for their SNES ports. Kiya, Takahashi, and others soon working on this series would iterate on the rock-solid foundation set here. The real downer is how quickly folks turn away from the series itself because it's either funnier or more convenient to crap on the third-first-person perspective. Few ARPG-dungeon crawler hybrids are as consistent, engrossing, and replayable as this.

The studio's largely moved on to more profitable pastures, with Ys and Trails being such huge tentpole series sucking up their time and resources. My kingdom for even a simple port of Brandish: The Dark Revenant to modern platforms! And my heart to those who give this series a chance.

1973

Lemonade Stand became a staple on Woz & Jobs' iconic people's computer, either as an activity for one classroom to a PC, or just another doodad at home. It's the first notable translation of Hamurabi's numbers game into a simpler, more immediate package, among many others up till today. While that '68 precursor evolved over time through successors like Santa Paravia en Fiumaccio, Jamison's take on the concept meant distilling its profits-and-losses text interactions and formulas to their essence. We're not planning for the survival and growth of a Mesopotamian city, just trying to run daily profits and manage assets for the local beverage counter. All the player's worried about are how many drinks to make, how many ad signs to buy, and how much to charge customers for a cup. It's as straightforward as it sounds, with only the occasional thunderstorm or street market threatening your sales.

Yes, this sounds as simplistic and repetitive as it is. Maybe that's the point, though. Running shop isn't as glamorous as it looks, even in this most accessible form. Players merely need to hunt and peck some keys, then watch the results fly by. There's some cute lil' intermissions for each new day (or inclement weather), accompanied by beeper sound arrangements of tunes from Singin' in the Rain and other classics. By and large, though, the game's beaten once you eliminate obviously bad or sub-optimal mathematical choices, eventually finding the optimal sales formulas for each scenario. Doing this on your first go, all within 12 days in most versions, is a bit more of a challenge, but irrelevant when it's so easy to just start over and steamroll past the RNG for a high cash total.

Back then, even this all-ages rendition of the resource management experience first digitized in Hamurabi would have seemed tricky, or at least addictive. It promotes a 1-to-1 narrative of modern capitalism as rational, mostly predictable, and viable at any rung of society. After all, if a mere kid can solicit this much money from passers-by on the sidewalk during a heat wave, then what's stopping you from making it onto Shark Tank, huh?! Well?! Let's just overlook any possibility of, oh I don't know, selling a bad product while your competitors run you out with any mixture of better or more cunning practices. Lemonade Stand doesn't wants its K-6 audience to consider bad guys robbing your startup business, or the HOA banning this (and garage sales, and solar panels, and [insert cool thing here]) entirely. Nice sentiments are nice, but trying to sugarcoat capitalism only works for so long. It's one thing if I'm playing a hyper-detailed and demanding economy sim, of course. I never expected any trenchant critique of, or answer to, the social-economic hierarchy failing us for the benefit of a few. MECC themselves would do that way later with Logical Journey of the Zoombinis, thankfully.

It's no secret that the lemonade stand's been a trojan-horse metaphor normalizing the American Dream to kids for who knows how long. The concept, its connotations, and all that pop culture imagery was practically inescapable for me, growing up in sunbaked suburban Texas. I never ran such an establishment, being too shy and awkward to exercise that entrepreneurial spirit still reinforced today. Moreover, it seemed increasingly irrelevant—theoretically sound, but way harder than it looks in practice. Girl Scout cookies are the closest equivalent I see in my area nowadays, and it's telling how the most successful kids only sell those thousands of batches because it's their parents' side-gig. The myth of the all-American lemonade stand and its variations dates back to a pre-Internet, pre-9/11 era of good feelings and busy neighborhoods which I've only had the smallest taste of as a late millennial.

Emulating this now is easy-peasy thanks to the Internet Archive. I played this on lunch break, even knowing pretty much exactly how it would go. The more interesting thing is to imagine those coat-swaddled students piling into class, early on a snowy Midwestern morning, expecting the same 'ol usual as their teacher introduces this odd monitor and keyboard to them all. The CRT's green glow fades into view, the floppy disk drive whirrs excitedly, and this impressionable set of youngsters get their first peek into the Information Age at their fingertips. Lemonade Stand always worked best as an educational tool, letting everyone share this technology which you once needed a teletype and printer to enjoy. By selling these games and Apple IIs to so many faculty, MECC themselves promoted a unique edu-tech model that itself mirrors the allegory of the kid's streetside booth. I'm glad to see that history's vindicated the story-driven, more ambiguous paradigm of Oregon Trail and other adventurous software, but I think this game represents the organization's classic era best. Pixel pedagogy would only go up in design efficacy and ambition from here, not that it's bad place to start—just one that's happy to date itself, a self-deprecating lesson if any.

1975

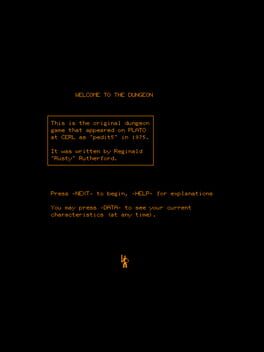

The definite article, or it would be if the mythical, swiftly deleted m199h PLATO game was as stat-heavy as alumni remember. All these old mainframe games ran the risk of removal and erasure, even programs we recognize now as essential in the history of interactive media. Like the souls of doomed adventurers lost in the dark, the most accessible of '60s and '70s computer video software lived and died on the whims of plucky creators vs. system operators and their bosses trying to maintain their services. Students at colleges using the now obsolete PLATO educational network and timesharing infrastructure made amazing time-wasters under these conditions. From them we got pivotal text-and-image pioneers in genres ranging from space sims to, of course, role-playing adventures.

The Dungeon, or pedit5 as it's known, was the first fully-featured dungeon crawling computerized role-playing game, made less than a year after the first edition of TSR's Dungeons & Dragons. You can play it today thanks to cyber, a modern PLATO emulator and network with pre-made demo user logins for anyone who'd like to try PLATO software. So I decided to get some quality time with the close ancestors of games like Beneath Apple Manor, Akalabeth, Rogue, and then the Ultima & Wizardry pantheons leading into today.

Building a character, or just choosing one of the legacy adventurers saved on cyber1, takes relatively little effort. It's nice to play with a cleaned-up, simplified form of the original D&D's character creation framework, needing only a few stats and some items to get started. pedit5, like most PLATO games preserved today, has a short, fairly usable manual you can consult before playing. It's not long before your stick-figure spelunker gets dropped into a series of eventful corridors, wireframe-thin as they are.

pedit5's main problems come from a mix of simplistic mechanics and the inability to escape death. Luck is definitely not on anyone's side here, except the monsters who will jump you and unceremoniously win or die. Combat's entirely automated past your decision to flee or fight, and more attention goes to finding secret doors and using spells out of battle. This auto-combat system is a kind of handwaving—designer Rusty Rutherford's way of saying he couldn't adapt the tabletop game's encounter mechanics. (It's also possible he just didn't have time to, being a student and having to evade PLATO's sys-ops while coding the game in a public channel.) Still, it's very unsatisfying to win a few scuffles, then get downed by the last monster you expect, only to try this non-randomized set of dungeon floors again.

There's still a good enough base here that later PLATO RPGs, mainly dnd and pedit5's successor orthanc, would use to great effect. As is, Rutherford's game was the spark others needed to try out TSR's revolutionary story-wargame system and make their own versions to play and share. This mirrored the tabletop market's own reactions to D&D, with competitors like Tunnels & Trolls + RuneQuest arriving not long. Graduates from the US Midwest who'd sunk their years into PLATO projects like this would themselves make games for the first wave of personal computers. Ever wonder how we got from scrappy little rulebooks to the likes of Final Fantasy? It all comes back to works like The Dungeon.

Shout-outs to whoever made the Spock character, among other pop culture personas you can choose to play. You don't see any of this reflected in the game's graphics, though they're nice and pristine compared to anything the initial batch of Apple II, TRS-80, and Commodore PET games could offer. Give pedit5 a try, or its improved sequel orthanc, but don't feel obligated to clear The Dungeon. I'm more interested in getting to the bottom of other PLATO classics, anyway.

The Dungeon, or pedit5 as it's known, was the first fully-featured dungeon crawling computerized role-playing game, made less than a year after the first edition of TSR's Dungeons & Dragons. You can play it today thanks to cyber, a modern PLATO emulator and network with pre-made demo user logins for anyone who'd like to try PLATO software. So I decided to get some quality time with the close ancestors of games like Beneath Apple Manor, Akalabeth, Rogue, and then the Ultima & Wizardry pantheons leading into today.

Building a character, or just choosing one of the legacy adventurers saved on cyber1, takes relatively little effort. It's nice to play with a cleaned-up, simplified form of the original D&D's character creation framework, needing only a few stats and some items to get started. pedit5, like most PLATO games preserved today, has a short, fairly usable manual you can consult before playing. It's not long before your stick-figure spelunker gets dropped into a series of eventful corridors, wireframe-thin as they are.

pedit5's main problems come from a mix of simplistic mechanics and the inability to escape death. Luck is definitely not on anyone's side here, except the monsters who will jump you and unceremoniously win or die. Combat's entirely automated past your decision to flee or fight, and more attention goes to finding secret doors and using spells out of battle. This auto-combat system is a kind of handwaving—designer Rusty Rutherford's way of saying he couldn't adapt the tabletop game's encounter mechanics. (It's also possible he just didn't have time to, being a student and having to evade PLATO's sys-ops while coding the game in a public channel.) Still, it's very unsatisfying to win a few scuffles, then get downed by the last monster you expect, only to try this non-randomized set of dungeon floors again.

There's still a good enough base here that later PLATO RPGs, mainly dnd and pedit5's successor orthanc, would use to great effect. As is, Rutherford's game was the spark others needed to try out TSR's revolutionary story-wargame system and make their own versions to play and share. This mirrored the tabletop market's own reactions to D&D, with competitors like Tunnels & Trolls + RuneQuest arriving not long. Graduates from the US Midwest who'd sunk their years into PLATO projects like this would themselves make games for the first wave of personal computers. Ever wonder how we got from scrappy little rulebooks to the likes of Final Fantasy? It all comes back to works like The Dungeon.

Shout-outs to whoever made the Spock character, among other pop culture personas you can choose to play. You don't see any of this reflected in the game's graphics, though they're nice and pristine compared to anything the initial batch of Apple II, TRS-80, and Commodore PET games could offer. Give pedit5 a try, or its improved sequel orthanc, but don't feel obligated to clear The Dungeon. I'm more interested in getting to the bottom of other PLATO classics, anyway.

1982

Two years before the birth of my favorite PBS documentary series, two monumental arcade shooters released in Japanese game centers. We mostly talk about Namco's Xevious today, but that's not to say Taito's Front Line is just a footnote. Real-time games had toyed with replicating the modern ground combat experience before, from Konami's tank excursion Strategy-X to the more tactical, stealth-focused Castle Wolfenstein by Silas Warner. The former stuck true to the reflexes-driven loop of contemporary vehicle action, whereas the latter hinted at a more realistic approach, boiling the essentials of wargame combat down into an accessible format. It's really Taito's game that first united vehicular and infantry play into a cohesive whole, albeit with many rough edges and quite the jump in difficulty.

Front Line stars a non-descript 20th-century doughboy thrust into the action, with no squad or commanding officers to lead you through the battlefield. This front observer's got just a regular automatic rifle and seemingly no end of grenades, but also an aptitude with commandeering armored cannons on treads. Fighting through interminable waves of conspicuously Axis-like troops and juggernauts requires players to manage their distance, time shots and lobs correctly, and find a sustainable rhythm in the heat of battle.