PasokonDeacon

1978

And we can try, to understand,

The Atari games' effect on Nam[co]

Whether you're a plumber or a cute dungeon crawler, you're indebted to Nam, you're indebted to Nam. But it's not alright—it's not even okay. And I can't look the other way. Toru Iwatani's first game shows all the growing pains & missteps you'd expect from an arcade developer dabbling in microchip games after years of electromechanical (eremeka) products. It's more than a curio, though. The beginnings of Pac-Man's cheeky fun show up even this early, if you can believe it. Just know it's not the real deal—the Hee Bee Gee Bees, if you will.

Speaking later in his career, an Iwatani then swamped with management duties asserted that "making video games is an act of kindness to others, a tangible gift of happiness." This axiom of purpose comes after his own complaints about the stagnation of '80s game centers, then flush with shoot-em-ups and less-than-innovative software. Around 1987, even Namco's own arcade output had trailed off in mechanical ambition, trading out the derring-do of Dragon Buster for the excellent but conventional Dragon Spirit. One could argue he had rose-tinted glasses this early, ignoring all the clones and production frenzy of Golden Age arcade games like his own. But he's arguing most for elegance and player-first design, something attempted with Gee Bee.

Conceived as a compromise between the pinball tables he wanted to make and Pres. Nakamura & co.'s interest in imports like Breakout, their 1978 debut had ambitions. It's an early go at combining multiple mechanics and score strategies found in Steve Wozniak's creation and post-war pinball designs. Anyone walking by the cab would see the vague, amusing outline of a human face made from barriers & breakables. Together with the requisite comical marquee & paddle, this would have seemed familiar enough to players at the time while enticing them with novelty. What's the bee chipping away at? Are we stinging our selves with delight as the blocks dissipate, our attacks moving faster and faster? That kind of imagination springs forth from even a premise as simple as this.

I'm sad to say that the mind-meld of pinball and electronic squash just wasn't feasible this early on. Gee Bee offers neither the flash and nuances of the best flipper games Chicago could offer, nor the pure and addictive game loop Wozniak wrought from Clean Sweep. Iwatani and his co-developers hamstrung themselves by refusing to commit one way or the other. There's a few too many ways to screw yourself over in Gee Bee, from less intuitive physics to the screen resetting every time you lose a ball. Inability to reach high scores is one thing, but that denial of progress is a buzzkill. All your careful threading of the needle to hit all the NAMCO letters for the multiplier can go to waste in an instant. All the patience needed to clear one upper half, thus blocking the ball from a previously open tunnel, feels like a cruel joke.

If what I'm saying gives you the heebie-jeebies, then don't overthink it. The game's recognizable to modern players, and fun for a little bit at least. But there's just no longevity here except for ardent score seekers. I can see why, for all of Namco's work to promote it, Gee Bee didn't take off at home or abroad. Space Invaders had innovated upon the destructive form of Pong that Breakout started, while this feels like an evolutionary dead-end. Bomb Bee & Cutie Q would try to salvage this with some success, of course. I'm just unsurprised that Iwatani learned from the mistakes made here, keeping that focus on levity & eclectic design in Pac-Man & Libble Rabble. On a technical level, this board still has some positives of note, mainly its fluidity & amount of color vs. the rest of the market. It's worth a try for historic value, and a sneak peek of the game development ethos Iwatani spread to other Namco notables in the coming years.

The Atari games' effect on Nam[co]

Whether you're a plumber or a cute dungeon crawler, you're indebted to Nam, you're indebted to Nam. But it's not alright—it's not even okay. And I can't look the other way. Toru Iwatani's first game shows all the growing pains & missteps you'd expect from an arcade developer dabbling in microchip games after years of electromechanical (eremeka) products. It's more than a curio, though. The beginnings of Pac-Man's cheeky fun show up even this early, if you can believe it. Just know it's not the real deal—the Hee Bee Gee Bees, if you will.

Speaking later in his career, an Iwatani then swamped with management duties asserted that "making video games is an act of kindness to others, a tangible gift of happiness." This axiom of purpose comes after his own complaints about the stagnation of '80s game centers, then flush with shoot-em-ups and less-than-innovative software. Around 1987, even Namco's own arcade output had trailed off in mechanical ambition, trading out the derring-do of Dragon Buster for the excellent but conventional Dragon Spirit. One could argue he had rose-tinted glasses this early, ignoring all the clones and production frenzy of Golden Age arcade games like his own. But he's arguing most for elegance and player-first design, something attempted with Gee Bee.

Conceived as a compromise between the pinball tables he wanted to make and Pres. Nakamura & co.'s interest in imports like Breakout, their 1978 debut had ambitions. It's an early go at combining multiple mechanics and score strategies found in Steve Wozniak's creation and post-war pinball designs. Anyone walking by the cab would see the vague, amusing outline of a human face made from barriers & breakables. Together with the requisite comical marquee & paddle, this would have seemed familiar enough to players at the time while enticing them with novelty. What's the bee chipping away at? Are we stinging our selves with delight as the blocks dissipate, our attacks moving faster and faster? That kind of imagination springs forth from even a premise as simple as this.

I'm sad to say that the mind-meld of pinball and electronic squash just wasn't feasible this early on. Gee Bee offers neither the flash and nuances of the best flipper games Chicago could offer, nor the pure and addictive game loop Wozniak wrought from Clean Sweep. Iwatani and his co-developers hamstrung themselves by refusing to commit one way or the other. There's a few too many ways to screw yourself over in Gee Bee, from less intuitive physics to the screen resetting every time you lose a ball. Inability to reach high scores is one thing, but that denial of progress is a buzzkill. All your careful threading of the needle to hit all the NAMCO letters for the multiplier can go to waste in an instant. All the patience needed to clear one upper half, thus blocking the ball from a previously open tunnel, feels like a cruel joke.

If what I'm saying gives you the heebie-jeebies, then don't overthink it. The game's recognizable to modern players, and fun for a little bit at least. But there's just no longevity here except for ardent score seekers. I can see why, for all of Namco's work to promote it, Gee Bee didn't take off at home or abroad. Space Invaders had innovated upon the destructive form of Pong that Breakout started, while this feels like an evolutionary dead-end. Bomb Bee & Cutie Q would try to salvage this with some success, of course. I'm just unsurprised that Iwatani learned from the mistakes made here, keeping that focus on levity & eclectic design in Pac-Man & Libble Rabble. On a technical level, this board still has some positives of note, mainly its fluidity & amount of color vs. the rest of the market. It's worth a try for historic value, and a sneak peek of the game development ethos Iwatani spread to other Namco notables in the coming years.

1974

ok 3 2 1 let's jam waggles to Cowboy Bebop as I light up the doobie and duel 'em

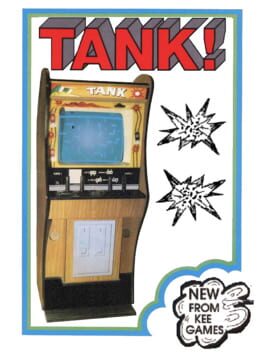

You have Kee Games to thank for gaming's original tank controls. I mean, it's in the name. But more than that, Steve Bristow's simpler take on the 1-on-1 vehicular combat of Spacewar! would end up saving Atari. Pong may have started that company's rise to fame, but the Pong market crash around the turn of 1974, plus the successful but loss-leading Gran Trak 10, put Bushnell & Dabney's venture on thin ice. The upstart, rockstar company that had made video games a fad almost met its demise, if not for the efforts of the affiliated company Bristow worked at.

Though technically a subsidiary of Atari, Kee Games had unique management and technical staff, such as experienced coin-op techie Bristow. They profited off of Pong clones while even Atari's originals couldn't, making waves in regions where Atari couldn't distribute. And then Tank happened. It quickly grew in popularity at trade shows and location tests, soon displacing the ailing Pong-likes that had flooded arcade and jukebox venues over the last year and a half. Atari's own Gran Trak 10, a revolution in arcade gaming, struggled to compete. What was so different this time?

Obviously this was and remains a very simple action game. You use two sticks to rotate or move back and forth, much like operating any construction or military treaded vehicle. But like Gran Trak, you weren't just shooting at the other player on an almost entirely black screen. The "course", or maze in Tank's case, let players strategize and tactically move towards and around each other. You could play mind games and take risky shots like never before, not even in then complex faire like Quadrapong. Just as fighting games today each have a meta, Bristow's game encouraged a similar kind of community learning and one-upmanship far beyond mere table tennis. The more complex controls didn't throw arcade-goers off—if anything, that added sense of realism or simulation made it more approachable.

In turn, Tank had finally achieved the "Spacewar! for the public" dream that Pitts & Tuck, Syzygy/Nutting, and then Atari had sought. Kee Games would sell more than a hundred thousand boards and cabinets through 1974 and beyond. Because Atari owned them with 90% company stock, this provided a financial and commercial boon. Tank and Gran Trak would, in tandem, prove that video games were more than a transient trend—coin-op businesses could expect these contraptions to improve, invent, and immerse their customers well beyond Pong.

Tank and its iterative sequels were so foundational for Atari & Kee Games that it would later influence their first multi-game cartridge console. The Atari VCS specifically borrows its iconic joystick design from a Tank II mini-console prototype, and an expanded port of Tank dubbed Combat was the main pack-in launch title alongside the system in 1977. While this may be as rudimentary as vehicular dueling has ever been, even compared to its space-borne predecessors, Tank's earned its place in arcade & video game history.

You have Kee Games to thank for gaming's original tank controls. I mean, it's in the name. But more than that, Steve Bristow's simpler take on the 1-on-1 vehicular combat of Spacewar! would end up saving Atari. Pong may have started that company's rise to fame, but the Pong market crash around the turn of 1974, plus the successful but loss-leading Gran Trak 10, put Bushnell & Dabney's venture on thin ice. The upstart, rockstar company that had made video games a fad almost met its demise, if not for the efforts of the affiliated company Bristow worked at.

Though technically a subsidiary of Atari, Kee Games had unique management and technical staff, such as experienced coin-op techie Bristow. They profited off of Pong clones while even Atari's originals couldn't, making waves in regions where Atari couldn't distribute. And then Tank happened. It quickly grew in popularity at trade shows and location tests, soon displacing the ailing Pong-likes that had flooded arcade and jukebox venues over the last year and a half. Atari's own Gran Trak 10, a revolution in arcade gaming, struggled to compete. What was so different this time?

Obviously this was and remains a very simple action game. You use two sticks to rotate or move back and forth, much like operating any construction or military treaded vehicle. But like Gran Trak, you weren't just shooting at the other player on an almost entirely black screen. The "course", or maze in Tank's case, let players strategize and tactically move towards and around each other. You could play mind games and take risky shots like never before, not even in then complex faire like Quadrapong. Just as fighting games today each have a meta, Bristow's game encouraged a similar kind of community learning and one-upmanship far beyond mere table tennis. The more complex controls didn't throw arcade-goers off—if anything, that added sense of realism or simulation made it more approachable.

In turn, Tank had finally achieved the "Spacewar! for the public" dream that Pitts & Tuck, Syzygy/Nutting, and then Atari had sought. Kee Games would sell more than a hundred thousand boards and cabinets through 1974 and beyond. Because Atari owned them with 90% company stock, this provided a financial and commercial boon. Tank and Gran Trak would, in tandem, prove that video games were more than a transient trend—coin-op businesses could expect these contraptions to improve, invent, and immerse their customers well beyond Pong.

Tank and its iterative sequels were so foundational for Atari & Kee Games that it would later influence their first multi-game cartridge console. The Atari VCS specifically borrows its iconic joystick design from a Tank II mini-console prototype, and an expanded port of Tank dubbed Combat was the main pack-in launch title alongside the system in 1977. While this may be as rudimentary as vehicular dueling has ever been, even compared to its space-borne predecessors, Tank's earned its place in arcade & video game history.

1982

So it goes, the repeating blunders of pi(lots). I can't help but laugh every time I hit the green & go boom, knowing it's as much a technical choice as absurd design. Believability aside, it's nice to face consequences for mismanaging your velocity & inertia. Just dodging the targets and naught else would get dull, an adjective I simply can't slap on River Raid.

Carol Shaw knew a good role model when she saw one. Konami's Scramble isn't quite as well-recognized today for the precedents it set, both for arcade shooters & genres beyond. Yet she was quick to adapt that game's scrolling, segmented yet connected world into something the VCS could handle. Making any equivalent of a tiered power-up system was out of the question, but River Raid compensates with its little touches. The skill progression in this title really sneaks up on you, much to my delight.

Acceleration, deceleration, & yanking that yoke—combine that with fuel management, plus the scoring rubric, and it's a lot more to absorb than normal for a VCS shooter. I made it to 50k points before feeling sated, having cleared maybe a couple tens of stages (neatly separated by the bridges you demolish), and I could go for seconds. Maybe some extra time & finesse could have added more of a soundscape here, albeit limited by the POKEY like usual. But there's a completeness, the beginnings of verisimilitude in this genre which you only saw inklings of before on consoles. Scramble's paradigm had come to the Atari.

Shaw's coding smarts are all over this, too. From pseudo-random endless shooting, to the play area using mirrored sections to minimize flickering, River Raid pushes its technical tier even beyond the smooth vertical scrolling. Going from 3D Tic-Tac-Toe to this must have felt triumphant. Her later works for Activision across Intellivision & succeeding Atari consoles carry on the pedigree made clear here. Worry not over fears of River Raid's reputation being outdated or unearned, reader. It's a worthy highlight of the 2600 library which I could fire up anytime in any mood.

Carol Shaw knew a good role model when she saw one. Konami's Scramble isn't quite as well-recognized today for the precedents it set, both for arcade shooters & genres beyond. Yet she was quick to adapt that game's scrolling, segmented yet connected world into something the VCS could handle. Making any equivalent of a tiered power-up system was out of the question, but River Raid compensates with its little touches. The skill progression in this title really sneaks up on you, much to my delight.

Acceleration, deceleration, & yanking that yoke—combine that with fuel management, plus the scoring rubric, and it's a lot more to absorb than normal for a VCS shooter. I made it to 50k points before feeling sated, having cleared maybe a couple tens of stages (neatly separated by the bridges you demolish), and I could go for seconds. Maybe some extra time & finesse could have added more of a soundscape here, albeit limited by the POKEY like usual. But there's a completeness, the beginnings of verisimilitude in this genre which you only saw inklings of before on consoles. Scramble's paradigm had come to the Atari.

Shaw's coding smarts are all over this, too. From pseudo-random endless shooting, to the play area using mirrored sections to minimize flickering, River Raid pushes its technical tier even beyond the smooth vertical scrolling. Going from 3D Tic-Tac-Toe to this must have felt triumphant. Her later works for Activision across Intellivision & succeeding Atari consoles carry on the pedigree made clear here. Worry not over fears of River Raid's reputation being outdated or unearned, reader. It's a worthy highlight of the 2600 library which I could fire up anytime in any mood.

1983

Green the putt. Ball the club. Falcom the Nihon. Meme the name.

Before Nintendo & HAL Laboratory codified the bare basics of home golf games—graphical aiming, multi-step power bar, you know the drill—experiments like this obscure Falcom release were the norm. They weren't alone: everyone from Atari to T&E Soft tried their hand at making either casual putt romps or hardcore simulations. Both consoles & micro-computers of the era were hard-pressed to make golf feel fun, even if they could simplify or complexify it. As a regular cassette game coded in BASIC, Computer the Golf always had humble aims, uninterested in changing trends.

I still managed to have a good time despite the archaic mechanics & presentation, however. Each hole's sensibly designed & placed to reflect growing expectations for player skill. Your club variety & multi-step power bar (yes, these existed before Nintendo's Golf!) also make precision shots easier to achieve. For 3500 yen, players would have gotten decent value, especially if you wanted something from Falcom with more of a puzzle feel. There's also the requisite scorecard feature, plus cursor key controls at a time when most PC-88 & FM-7 releases stuck with numpad keys.

The game's code credits Norihiko Yaku as programmer, and very likely the only creator involved. It's hard to remember a time when just one person could make a fully-featured home game, let alone at Falcom prior to their massive '80s successes. I appreciate the quaintness & low stakes of this pre-Xanadu, pre-Ys software you'd just find on the shelf in a bag, sitting next to all those Apple II imports that started the company. Soon you'd have naught but xRPGs & graphic adventures from the studio, all requiring more and more talented people to create. Sorcerian & Legacy of the Wizard make no mention of bourgeois sports; that's for the rest of bubble-era Japan to covet!

Maybe this will remain a footnote, but it's an inoffensive one. It's ultimately one of the best J-PC sports games for its era, right alongside T&E Soft's fully 3D efforts. Paradigm shifts would come with No. 1 Golf on Sharp X1, then Nintendo's Golf and competing pro golf series from Enix & Telenet. The times were a-changin'.

Before Nintendo & HAL Laboratory codified the bare basics of home golf games—graphical aiming, multi-step power bar, you know the drill—experiments like this obscure Falcom release were the norm. They weren't alone: everyone from Atari to T&E Soft tried their hand at making either casual putt romps or hardcore simulations. Both consoles & micro-computers of the era were hard-pressed to make golf feel fun, even if they could simplify or complexify it. As a regular cassette game coded in BASIC, Computer the Golf always had humble aims, uninterested in changing trends.

I still managed to have a good time despite the archaic mechanics & presentation, however. Each hole's sensibly designed & placed to reflect growing expectations for player skill. Your club variety & multi-step power bar (yes, these existed before Nintendo's Golf!) also make precision shots easier to achieve. For 3500 yen, players would have gotten decent value, especially if you wanted something from Falcom with more of a puzzle feel. There's also the requisite scorecard feature, plus cursor key controls at a time when most PC-88 & FM-7 releases stuck with numpad keys.

The game's code credits Norihiko Yaku as programmer, and very likely the only creator involved. It's hard to remember a time when just one person could make a fully-featured home game, let alone at Falcom prior to their massive '80s successes. I appreciate the quaintness & low stakes of this pre-Xanadu, pre-Ys software you'd just find on the shelf in a bag, sitting next to all those Apple II imports that started the company. Soon you'd have naught but xRPGs & graphic adventures from the studio, all requiring more and more talented people to create. Sorcerian & Legacy of the Wizard make no mention of bourgeois sports; that's for the rest of bubble-era Japan to covet!

Maybe this will remain a footnote, but it's an inoffensive one. It's ultimately one of the best J-PC sports games for its era, right alongside T&E Soft's fully 3D efforts. Paradigm shifts would come with No. 1 Golf on Sharp X1, then Nintendo's Golf and competing pro golf series from Enix & Telenet. The times were a-changin'.

2013

To some, Hydlide's redemption. To me, a reminder of what already worked. Revived-lyde, if you will. /dadjoke

Nostalgia is a fickle thing to design around. Lean too hard on it and your game's core will collapse under the pressure of memories. Promise but under-deliver and you'll turn players off in due time. Fairune isn't a lot more than polished pastiche-cum-homage, but I believe it takes the premise of 1984's Hydlide & adjacent games to near its limits. All the old elements are here, just refined for a newer, more critical audience.

Yes, once upon a time in a land not so far away, game fans got a lot of enjoyment from the most basic of adventures with stat progression. Hydlide took its essentials from Tower of Druaga, placing that game's schoolyard secrets manifesto into a home play venue. This makes it difficult, if not frustrating to play today for anyone expecting what most consider intuitive design. That said, I think too many dismiss not just what Hydlide accomplished in its time, but how elegant it was & still is. Sure, you're bumbling around an overworld & dungeons looking for any possible hint towards progress. But in this way, it succeeds in mixing the classic adventure, puzzle, & dungeon crawling genres, creating a journey both timely yet archetypal.

If Hydlide's the role-playing adventure that canon forgot (or too quickly disqualified), then Fairune's the rejuvenation of all T&E Soft's game represented. I had so much fun traversing this small but detailed land, uncovering its oddities and flowing from one power tier to the next. Here, the nostalgia comes less from simply aping its predecessors, hoping for an easy connection to players. Rather, the excellently presented fantasy world & tropes convey a kind of pre-Tolkein fiction, both celebrated & demystified. Out with the enigmatic solutions, in with the peeling skin of what Hydlide sought to achieve.

The final boss becoming a classic arcade shooter is a bit too cute, though. (Even considering Hydlide creator Tokihiro Naito's own penchant for STGs, this was too on-the-nose.) And the game can only immerse you so much into this primordial high fantasy structure without iterating on its mechanics the way Fairune 2 does. But I think Skipmore's original throwback ARPG is a panacea for any discussions revolving around Hydlide & its place in game design history. The original J-PC game made a critical leap from Druaga's coin-feeding gatekeeping to a more palatable, individualized experience you could still share with friends & other gamers. Fairune recaptures the novelty, strangeness, and sekaikan that Hydlide's fans felt in the mid-'80s, just for today's players.

Even if I much prefer the sequel for how it posits a world where Hydlide's sequels didn't overcomplicate themselves to ill end, there's every reason to replay the prequel. Do yourself a favor and try this out for size. It might have you thinking twice about laughing off proto-Zelda examples of the genre.

Nostalgia is a fickle thing to design around. Lean too hard on it and your game's core will collapse under the pressure of memories. Promise but under-deliver and you'll turn players off in due time. Fairune isn't a lot more than polished pastiche-cum-homage, but I believe it takes the premise of 1984's Hydlide & adjacent games to near its limits. All the old elements are here, just refined for a newer, more critical audience.

Yes, once upon a time in a land not so far away, game fans got a lot of enjoyment from the most basic of adventures with stat progression. Hydlide took its essentials from Tower of Druaga, placing that game's schoolyard secrets manifesto into a home play venue. This makes it difficult, if not frustrating to play today for anyone expecting what most consider intuitive design. That said, I think too many dismiss not just what Hydlide accomplished in its time, but how elegant it was & still is. Sure, you're bumbling around an overworld & dungeons looking for any possible hint towards progress. But in this way, it succeeds in mixing the classic adventure, puzzle, & dungeon crawling genres, creating a journey both timely yet archetypal.

If Hydlide's the role-playing adventure that canon forgot (or too quickly disqualified), then Fairune's the rejuvenation of all T&E Soft's game represented. I had so much fun traversing this small but detailed land, uncovering its oddities and flowing from one power tier to the next. Here, the nostalgia comes less from simply aping its predecessors, hoping for an easy connection to players. Rather, the excellently presented fantasy world & tropes convey a kind of pre-Tolkein fiction, both celebrated & demystified. Out with the enigmatic solutions, in with the peeling skin of what Hydlide sought to achieve.

The final boss becoming a classic arcade shooter is a bit too cute, though. (Even considering Hydlide creator Tokihiro Naito's own penchant for STGs, this was too on-the-nose.) And the game can only immerse you so much into this primordial high fantasy structure without iterating on its mechanics the way Fairune 2 does. But I think Skipmore's original throwback ARPG is a panacea for any discussions revolving around Hydlide & its place in game design history. The original J-PC game made a critical leap from Druaga's coin-feeding gatekeeping to a more palatable, individualized experience you could still share with friends & other gamers. Fairune recaptures the novelty, strangeness, and sekaikan that Hydlide's fans felt in the mid-'80s, just for today's players.

Even if I much prefer the sequel for how it posits a world where Hydlide's sequels didn't overcomplicate themselves to ill end, there's every reason to replay the prequel. Do yourself a favor and try this out for size. It might have you thinking twice about laughing off proto-Zelda examples of the genre.