PasokonDeacon

1985

Or, as my backronym addled brain would tell me: Truly Hard, Early eXceptional DOS-era Evil Robodungeon. 1 mecha, 2 transformations, 15 complex levels, and infinite loops. Better start jetting and blasting.

Thexder was to PC-88 what Super Mario Bros. was to NES. Game Arts hit the motherlode when releasing their debut, a PC-88 action dungeon-crawler modeled after Atari's vector game Major Havoc. 1985 saw a major upswing in adoption of the PC-88, then NEC's beefiest 8-bit home computer. (Hey, guess which platform isn't associated with Thexder on IGDB yet? That's right, the one it was originally made for! Go team! /seething) With a new upgraded model on the horizon, these ex-ASCII programmers formed Game Arts with hopes of making an arcade classic for the home player. Hibiki Godai and Satoshi Uesaka's final game ended up becoming the PC-88's killer app, selling the faster mkIISR models in droves.

Suffice to say, both Square and Sierra On-Line were impressed enough to make their own ports, the former to MSX and Famicom while the latter brought Thexder overseas to IBM-compatible PCs. The DOS port thankfully rebalances the often harsh difficulty of the original. You take less damage and have an easier time collecting health & power-ups, that's for sure. While Thexder '85 is quite fun and beatable, it's also as brutal as you'd expect for an early foray into multi-stage mecha action with stats and memorization. Game Arts clearly wanted their players to clear at least the first loop, but it's tough going until you know some secrets and enemy patterns. I've beaten the DOS version a couple times now, so try that first if you want a faithful but accessible experience.

The whole appeal of Thexder comes from its mech-to-plane dynamics, where you swap between forms to use either the former's auto-targeting laser or the latter's speed and smaller size. Both modes let you navigate each techno-industrial maze while eliminating hordes of varied enemies, plus nabbing repair pick-ups along the way. Early stages ease you into the mechanics about as well as Nintendo's own games from the time, all before changing scenery and heading into caves full of nastiness. I always get a palpable sense of "where the hell is this mission taking me?" the closer I get to the end, even knowing the few boss encounters due to arrive. Having to weigh tradeoffs between your forms, plus carefully proceeding through hazardous areas you may or may not know, adds a satisfying tension to Game Arts' labyrinths. It may be a ruthless one to start with, but clearing it remains fulfilling, like defeating the Tower of Druaga which players would have been familiar with at the time.

It's awesome to see how effectively the team adapted Major Havoc into a richer adventure. The evolution from 1984's few screens' worth of level design, to Thexder having 4x that amount a level on average…games were improving so damn fast in that era. What might seem quaint or downright hostile was innovative back then, and shows its cleverness even today.

With a catchy musical theme and colorful, fluid scrolling visuals at a time when the PC-88 lent itself best to static adventure and sim./strategy titles, Thexder stood out. It proved that talented developers could squeeze anything out of NEC's hobbyist system, from intense arcade-style titles like this to more elaborate sagas like Ys or Uncharted Waters. And it gave new system owners the meaty, multi-playthrough software they needed at a time when Nintendo's Famicom and the arcades were far eclipsing Japanese PC games in immediate appeal. The era of simplistic, monochrome PC-8001 games was out; the FM-synth wielding, level-scrolling PC-88 releases were coming hard and fast. Game Arts led the charge with Thexder, Cuby Panic, and Silpheed, all of which earned their classic status in the midst of the J-PC gaming golden age.

Thexder was to PC-88 what Super Mario Bros. was to NES. Game Arts hit the motherlode when releasing their debut, a PC-88 action dungeon-crawler modeled after Atari's vector game Major Havoc. 1985 saw a major upswing in adoption of the PC-88, then NEC's beefiest 8-bit home computer. (Hey, guess which platform isn't associated with Thexder on IGDB yet? That's right, the one it was originally made for! Go team! /seething) With a new upgraded model on the horizon, these ex-ASCII programmers formed Game Arts with hopes of making an arcade classic for the home player. Hibiki Godai and Satoshi Uesaka's final game ended up becoming the PC-88's killer app, selling the faster mkIISR models in droves.

Suffice to say, both Square and Sierra On-Line were impressed enough to make their own ports, the former to MSX and Famicom while the latter brought Thexder overseas to IBM-compatible PCs. The DOS port thankfully rebalances the often harsh difficulty of the original. You take less damage and have an easier time collecting health & power-ups, that's for sure. While Thexder '85 is quite fun and beatable, it's also as brutal as you'd expect for an early foray into multi-stage mecha action with stats and memorization. Game Arts clearly wanted their players to clear at least the first loop, but it's tough going until you know some secrets and enemy patterns. I've beaten the DOS version a couple times now, so try that first if you want a faithful but accessible experience.

The whole appeal of Thexder comes from its mech-to-plane dynamics, where you swap between forms to use either the former's auto-targeting laser or the latter's speed and smaller size. Both modes let you navigate each techno-industrial maze while eliminating hordes of varied enemies, plus nabbing repair pick-ups along the way. Early stages ease you into the mechanics about as well as Nintendo's own games from the time, all before changing scenery and heading into caves full of nastiness. I always get a palpable sense of "where the hell is this mission taking me?" the closer I get to the end, even knowing the few boss encounters due to arrive. Having to weigh tradeoffs between your forms, plus carefully proceeding through hazardous areas you may or may not know, adds a satisfying tension to Game Arts' labyrinths. It may be a ruthless one to start with, but clearing it remains fulfilling, like defeating the Tower of Druaga which players would have been familiar with at the time.

It's awesome to see how effectively the team adapted Major Havoc into a richer adventure. The evolution from 1984's few screens' worth of level design, to Thexder having 4x that amount a level on average…games were improving so damn fast in that era. What might seem quaint or downright hostile was innovative back then, and shows its cleverness even today.

With a catchy musical theme and colorful, fluid scrolling visuals at a time when the PC-88 lent itself best to static adventure and sim./strategy titles, Thexder stood out. It proved that talented developers could squeeze anything out of NEC's hobbyist system, from intense arcade-style titles like this to more elaborate sagas like Ys or Uncharted Waters. And it gave new system owners the meaty, multi-playthrough software they needed at a time when Nintendo's Famicom and the arcades were far eclipsing Japanese PC games in immediate appeal. The era of simplistic, monochrome PC-8001 games was out; the FM-synth wielding, level-scrolling PC-88 releases were coming hard and fast. Game Arts led the charge with Thexder, Cuby Panic, and Silpheed, all of which earned their classic status in the midst of the J-PC gaming golden age.

1979

As said by a wise old sage: "be rootin', be tootin', and by Kong be shootin'...but most of all, be kind."

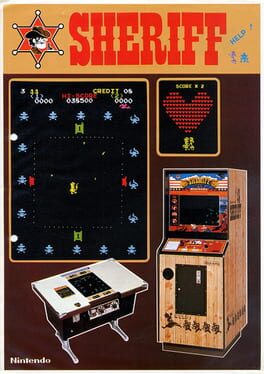

Everyone remembered the OK Corral differently. The Earps and feuding families each had their self-serving accounts of the shootout. John Ford, Stuart Lake, and other myth-makers turned the participants into legends, models of masculinity, freedom-seekers, and a long-lost Old West But the truth's rarely so glamorous or controversial. Just as the OK Corral gunfight never took place in the corral itself, Nintendo's Sheriff was never just the handiwork of a newly-hired Shigeru Miyamoto. How vexing it is that the echoes of Western mythologizing reach this far!

I am exaggerating a bit with regards to how Nintendo fans & gamers at large view this game. Miyamoto's almost always discussed in relation to Sheriff as an artist & assistant designer, not the producer (that'll be Genyo Takeda, later of StarTropics fame). That's not to diminish what the famous creator did contribute. While Nintendo largely put out clones and what I'd charitably call "experiments" by this point, their '79 twin-stick shooter defies that trend. It's still a bit rough-hewn, like any old cowboy, yet very fun and replayable.

Compared to earlier efforts like Western Gun & Boot Hill, there's more creative bending of Wild West stereotypes here, to mixed results. Though not the first major arcade game with an intermission, the scenes here are cute, a sign that the Not Yet Very Big N's developers were quick to match their competition. I do take umbrage with translating Space Invaders' aliens to bandits, though. Sure, this long predates modern discussions about negative stereotyping in games media, but that hardly disqualifies it. Let's just say that this game's rather unkind to its characters, from the doofy-looking lawman to his blatant damsel-in-distress & beyond. Respect to the condor, though. That's some gumption, flying above the fray on this baleful night, just askin' fer a plummet.

The brilliant part here is giving you solid twin-stick controls for moving & shooting well ahead of Midway's Robotron 2084. The dim bit is those enemy bullets, slow as molasses and firing only in cardinal directions. Normally you or the operator could just flip a DIP switch to raise the difficulty, but those options are absent too. What results is a fun, but relatively easy take on the Invaders template, one which rewards you a bit too much prior to developing the skills encouraged in Taito's originals. For example, it's much easier to aggressively fire here than to take cover, given the easily ignorable shields & posts. Your dexterity here compared to Space Invaders, or even Galaxian, tends to outweigh your opponents, for better and worse.

A counter-example comes when a few bandits charge into the corral, able to lunge at you if you trot too close. This spike in danger is exciting, an alternative to Galaxian's waves system which similarly revolutionizes your play-space. Where once you could just snipe at leisure, now you have to keep distance or get stabbed in the back! Of course, ranged exchanges were all that happened at the OK Corral. A little artistic liberty playing up the tropes can work out after all. Perhaps our strapping Roy Rogers believes in good 'ol fashioned marksmanship; he's a fool to deny himself fisticuffs, but a brave one.

When I'm not gunning down the circle of knives or playing matador with them, I think about how simple but compelling the game's premise is. We've gone from one Wild West tropset (the Mexican standoffs seen in Gunman & its ilk) to another, more politically charged one. You may be a lone marshall, but not much more than a deputized gang shooter. The game inadvertently conveys a message of liquid morality & primacy of who's more immediately anthropomorphic—empowering the Stetson hat over the sombrero. All basic American History 101 stuff, but displayed this vividly, this blatantly in a game this early? This seems less so Miyamoto's charm, more so his accidental wit.

Life's just too easy for the Wyatt Earps of this fictionalized, simplistic world. Another round in the corral, another kiss in the saloon, rinse and repeat. Maybe I'm giving too much credit to a one-and-done go at complexifying the paradigm Taito started, but it's filling food for thought. I highly recommend at least trying Sheriff today just to experience its odd thrills & ersatz yet perceptive view of the corral shootout tradition. The Fords & Miyamotos of the world, working with film & video games in their infancy, had a knack for making the most of limited possibilities. For all my misgivings, the distorted tales of the Old West are ample fodder for a destructive ride on the joysticks. Sheriff's team would go on to make works as iconic as Donkey Kong, so why downplay their earliest attempts to work with material as iconic as this?

I'm sure Sheriff will came back 'round these parts, like a tumbleweed hops from Hollywood ghost towns to the raster screen. Don't lemme see ya causin' trouble in The Old MAME, son.

Everyone remembered the OK Corral differently. The Earps and feuding families each had their self-serving accounts of the shootout. John Ford, Stuart Lake, and other myth-makers turned the participants into legends, models of masculinity, freedom-seekers, and a long-lost Old West But the truth's rarely so glamorous or controversial. Just as the OK Corral gunfight never took place in the corral itself, Nintendo's Sheriff was never just the handiwork of a newly-hired Shigeru Miyamoto. How vexing it is that the echoes of Western mythologizing reach this far!

I am exaggerating a bit with regards to how Nintendo fans & gamers at large view this game. Miyamoto's almost always discussed in relation to Sheriff as an artist & assistant designer, not the producer (that'll be Genyo Takeda, later of StarTropics fame). That's not to diminish what the famous creator did contribute. While Nintendo largely put out clones and what I'd charitably call "experiments" by this point, their '79 twin-stick shooter defies that trend. It's still a bit rough-hewn, like any old cowboy, yet very fun and replayable.

Compared to earlier efforts like Western Gun & Boot Hill, there's more creative bending of Wild West stereotypes here, to mixed results. Though not the first major arcade game with an intermission, the scenes here are cute, a sign that the Not Yet Very Big N's developers were quick to match their competition. I do take umbrage with translating Space Invaders' aliens to bandits, though. Sure, this long predates modern discussions about negative stereotyping in games media, but that hardly disqualifies it. Let's just say that this game's rather unkind to its characters, from the doofy-looking lawman to his blatant damsel-in-distress & beyond. Respect to the condor, though. That's some gumption, flying above the fray on this baleful night, just askin' fer a plummet.

The brilliant part here is giving you solid twin-stick controls for moving & shooting well ahead of Midway's Robotron 2084. The dim bit is those enemy bullets, slow as molasses and firing only in cardinal directions. Normally you or the operator could just flip a DIP switch to raise the difficulty, but those options are absent too. What results is a fun, but relatively easy take on the Invaders template, one which rewards you a bit too much prior to developing the skills encouraged in Taito's originals. For example, it's much easier to aggressively fire here than to take cover, given the easily ignorable shields & posts. Your dexterity here compared to Space Invaders, or even Galaxian, tends to outweigh your opponents, for better and worse.

A counter-example comes when a few bandits charge into the corral, able to lunge at you if you trot too close. This spike in danger is exciting, an alternative to Galaxian's waves system which similarly revolutionizes your play-space. Where once you could just snipe at leisure, now you have to keep distance or get stabbed in the back! Of course, ranged exchanges were all that happened at the OK Corral. A little artistic liberty playing up the tropes can work out after all. Perhaps our strapping Roy Rogers believes in good 'ol fashioned marksmanship; he's a fool to deny himself fisticuffs, but a brave one.

When I'm not gunning down the circle of knives or playing matador with them, I think about how simple but compelling the game's premise is. We've gone from one Wild West tropset (the Mexican standoffs seen in Gunman & its ilk) to another, more politically charged one. You may be a lone marshall, but not much more than a deputized gang shooter. The game inadvertently conveys a message of liquid morality & primacy of who's more immediately anthropomorphic—empowering the Stetson hat over the sombrero. All basic American History 101 stuff, but displayed this vividly, this blatantly in a game this early? This seems less so Miyamoto's charm, more so his accidental wit.

Life's just too easy for the Wyatt Earps of this fictionalized, simplistic world. Another round in the corral, another kiss in the saloon, rinse and repeat. Maybe I'm giving too much credit to a one-and-done go at complexifying the paradigm Taito started, but it's filling food for thought. I highly recommend at least trying Sheriff today just to experience its odd thrills & ersatz yet perceptive view of the corral shootout tradition. The Fords & Miyamotos of the world, working with film & video games in their infancy, had a knack for making the most of limited possibilities. For all my misgivings, the distorted tales of the Old West are ample fodder for a destructive ride on the joysticks. Sheriff's team would go on to make works as iconic as Donkey Kong, so why downplay their earliest attempts to work with material as iconic as this?

I'm sure Sheriff will came back 'round these parts, like a tumbleweed hops from Hollywood ghost towns to the raster screen. Don't lemme see ya causin' trouble in The Old MAME, son.

1994

The rose campion, a perennial pink-ish carnation found throughout temperate regions, has long been the study of biologists and botanists, from Darwin to Mendel. Now called silene coronaria, it formerly bore the designation lychnis, associated with a herbivorous moth of the same name, both fragile and humble. In this sense, this duo's unlikely contributions to modern life sciences mirror that of the original Korean PC platformer sharing the moniker, itself a key release for its field. I wish I could more easily recommend Softmax's first release beyond its historic significance, as the game itself is frustratingly unpolished and shows so much missed potential. But like its namesake, one shouldn't expect too much from what's just the beginnings of these ludo-scientists' forays into genres once untenable in this realm.

Video games in South Korea during the early '90s (well before today's glut of MMOs and mobile Skinner boxes) fell into two boxes: action-packed arcade releases and slower, more story-driven xRPGs and puzzlers on IBM-compatible PCs. The relative lack of consoles in the country—first because of low-quality bootlegs and second due to government bans on certain Japanese exports in the aftermath of WWII—meant that home enthusiasts needed a desktop computer to try anything outside the game centers. Anyone in the Anglosphere from that era can attest to so many CGA-/EGA-age struggles with rendering fast scrolling scenes and action, a feat relegated to works like Commander Keen or the occasional shoot-em-up such as Dragon Force: The Day 3. Even ambitious early iterations on JP-imported genres like the action-RPG suffered from choppy performance and limited colors, as was the case for Zinnia. VGA video and graphics accelerators, plus the rise of Windows 95 and GPUs, meant that PC compatibles could finally compete with TV hardware on arcade-like visuals and the aspirations that made possible. Lychnis was arguably the first non-STG Korean home title to herald this change.

Made by Artcraft, a grassroots team led by Hyak-kun Kim (later head of Gravity, creators of Ragnarok Online) and Yeon-kyu Choe (main director at publisher Softmax, leading tentpole series like War of Genesis), this was hardly an auspicious project. Yes, proving that VGA-equipped PCs just entering the market could handle something akin to Super Mario World was a challenge, but they didn't have much time or budget to make this a reality. And that shows throughout most of Lychnis' 15 levels, varying wildly in design quality, variety, and conveyance to players. I suspect that, like so many Korean PC games up through the turn of the millennium, this didn't get much playtesting beyond the developers themselves, who obviously knew how to play their own game quite well. Nor does this floppy-only game always play ball in DOSBox; whatever you do, keep the sound effects set to PC speaker, or this thing will just crash before you can even get past the vanity plate!

Still, the Falcom-esque opening sequence and fantasy artwork, vibrant and rich with that signature '90s D&D-inspired look, shows a lot of promise for new players. Same goes for the AdLib FM-synth soundtrack and crunchy PCM sound throughout your playthrough, with bubbly driving melodies fitting each world and a solid amount of aural feedback during tough action or platforming. There's a surprising amount of polish clashing against jank, which made my experience all the more beguiling. How could a team this evidently talented drop the ball in some very key areas? Was this the result of a rocky dev cycle, perhaps the main reason why Kim and Choe both splintered after this game and brought different friends to different companies? Just as the moth feeds upon the flower, this experiment in translating arcade and console play to monitor and keyboard was just one more casualty that would repeat itself, followed by other small studios making action/platformer/etc. debuts before working towards beefier software.

Lychnis drew in crowds of malnourished PC gamers with its heavy amount of smooth vertical and horizontal scrolling, harkening to the likes of Sonic and other mascots. (There's even a porcupine baddie early in the game which feels like an ode to SEGA's superstar.) Its premise also has a cute young adult appeal, with you choosing either the wall-jumping titular character in knight's armor, or his friend Iris, a cheeky mage with a very useful double jump and projectiles. Either way, we're off to defeat an evil sorcerer hell-bent on reviving ancient powers to conquer the continent of Laurasia. The worlds we visit reflect that treacherous journey away from home, starting in verdant fields, hills, and skies before ending within Sakiski's dread citadel full of traps and monsters. Anyone who's played a classic Ys story should recognize the similarities, and parts of this adventure brought Adol's trials in Esteria or Felghana to mind.

However, this still most resembles a platformer more like Wardner, Rastan, or the aforementioned Mario titles on Super Nintendo. The game loop consists of reaching each level's crystalline endpoint and then visiting the shop if you've acquired the requisite keycard. Pro tip: raise max continues to 5 and lives to 7. Lychnis doesn't ramp up its difficult right from the get-go, but World 1-3 presents the first big challenge, an arduous auto-scrolling climb from trees to clouds with no checkpoints whatsoever. I couldn't help but feel the designers struggled to decide if this would focus on 1CC play or heavy continues usage. There's a couple levels, both auto-scrollers, placed around mid-game which are very clearly meant to force Game Overs upon unsuspecting players who aren't concentrating and memorizing. Your lack of control per jump makes Iris the easy pick just for having more opportunities to correct trajectory, both for gaps and to keep distance from enemies and their attacks. Progressing through stages rarely feels that confusing in a navigation sense, but most present puzzles of varying efficacy which can impede you and lead to retries. With no saves or passwords, nor ways to gain continues or lives through high scores, this journey's very unforgiving for most today.

Thankfully there's only one case of multiple dubiously engineered levels in a row, unfortunately coming a bit early with 2-2 and 2-3. The former's just outright broken unless you play a certain way, having to time your attacks and positioning upon each set of mine-carts as tons of obstacles threaten to knock you off. Someone in the office must have had a penchant for auto-scrollers, which live up to their foul reputation whenever they appear here. (I'll cut 3-3 some slack for having a more unique combat-heavy approach, plus being a lot shorter, but it's still a waste of space vs. a fully fleshed-out exploratory jaunt across the seas.) 2-3, meanwhile, shows how masochistic Lychnis can get, with many blind jumps, sudden bursts of enemies from off-screen knocking you down bottomless pits, and lava eruptions casting extra hazards down upon you for insult to injury. Contrast this with the demanding but far fairer platforming gauntlets in 2-1, 3-2, and all of World 4's surprisingly non-slippery icy reaches. "All over the place" describes the content on offer here, and I could hardly accuse Artcraft of, um, crafting a boring or indistinct trip across these biomes.

What Lychnis does excel at is its pacing and means of livening up potential filler via an upgrades system. Thoroughly exploring stages, and clearing as many enemies and chests as you can find, builds up your coffers over time. Survive long enough, farm those 1-Ups and gold sacks, and eventually those top-tier weapons and armor are affordable, plus the ever nifty elixir that refills your life once between shops. This learn-die-hoard-buy loop takes most of the sting away from otherwise mirthless runs through these worlds, but is unfortunately tied to the game's most egregious failing: its one and only boss fight. Ever wonder how the rock-paper-scissors encounters from classic Alex Kidd games could get worse?! This game manages it by basically having you play slots with the big bad, where one either matches all symbols for damage or fails and takes a beating themselves. Only having the best gear makes this climactic moment reliably winnable, which I think is a step too far towards punishing all players, even the most skilled. It sucks because I kind of enjoy 5-3 right before, a very dungeon crawler-esque finale with lots of mooks to juggle and careful resource management. The ending sequence itself is as nice and triumphant as I'd expect, but what came right before was a killjoy.

I've shown a lot of mixed feelings for this so far, yet I still would recommend Lychnis to any classic 2D bump-and-jump aficionados who can appreciate the history behind this Frankenstein. For all my misgivings, it still felt to satisfying to learn the ins and outs, optimize my times, and somewhat put to rest that sorcerer's curse of not having played many Korean PC games. Of course, both Softmax and its offshoot Gravity would soon well surpass this impressive but unready foundation, whose success led to the frenetic sci-fi blockbuster Antman 2 and idiosyncratic pre-StarCraft strategy faire like Panthalassa. I suspect this thorny rose among Korean classics won't rank with many others waiting in my backlog, not that it's done a disservice by those later games fulfilling Artcraft's vision and promises of DOS-/Windows-era software finally reaching the mainstream. The biggest shame is how fragile that region's games industry has always been, from early dalliances with bootlegs and largely text-driven titles to the market constricting massively towards MMOs and other stuff built only for Internet cafes (no shade to those, though).

Just about the biggest advantage these classic Korean floppy and CD releases have over, say, anything for PC-98 is their ease of emulation. Lychnis remains abandonware, the result of its publisher not caring to re-release or even remaster this for Steam and other distributors. Free downloads are just a hop and a skip away, though none of these games have anything like the GOG treatment. With recent news of Project EGG bringing classic Japanese PC games to Switch, though, perhaps there's a chance that other East Asian gems and curiosities can find a place in the sun once more. Well, I can dream.

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Mar. 14 - 20, 2023 LATE

Video games in South Korea during the early '90s (well before today's glut of MMOs and mobile Skinner boxes) fell into two boxes: action-packed arcade releases and slower, more story-driven xRPGs and puzzlers on IBM-compatible PCs. The relative lack of consoles in the country—first because of low-quality bootlegs and second due to government bans on certain Japanese exports in the aftermath of WWII—meant that home enthusiasts needed a desktop computer to try anything outside the game centers. Anyone in the Anglosphere from that era can attest to so many CGA-/EGA-age struggles with rendering fast scrolling scenes and action, a feat relegated to works like Commander Keen or the occasional shoot-em-up such as Dragon Force: The Day 3. Even ambitious early iterations on JP-imported genres like the action-RPG suffered from choppy performance and limited colors, as was the case for Zinnia. VGA video and graphics accelerators, plus the rise of Windows 95 and GPUs, meant that PC compatibles could finally compete with TV hardware on arcade-like visuals and the aspirations that made possible. Lychnis was arguably the first non-STG Korean home title to herald this change.

Made by Artcraft, a grassroots team led by Hyak-kun Kim (later head of Gravity, creators of Ragnarok Online) and Yeon-kyu Choe (main director at publisher Softmax, leading tentpole series like War of Genesis), this was hardly an auspicious project. Yes, proving that VGA-equipped PCs just entering the market could handle something akin to Super Mario World was a challenge, but they didn't have much time or budget to make this a reality. And that shows throughout most of Lychnis' 15 levels, varying wildly in design quality, variety, and conveyance to players. I suspect that, like so many Korean PC games up through the turn of the millennium, this didn't get much playtesting beyond the developers themselves, who obviously knew how to play their own game quite well. Nor does this floppy-only game always play ball in DOSBox; whatever you do, keep the sound effects set to PC speaker, or this thing will just crash before you can even get past the vanity plate!

Still, the Falcom-esque opening sequence and fantasy artwork, vibrant and rich with that signature '90s D&D-inspired look, shows a lot of promise for new players. Same goes for the AdLib FM-synth soundtrack and crunchy PCM sound throughout your playthrough, with bubbly driving melodies fitting each world and a solid amount of aural feedback during tough action or platforming. There's a surprising amount of polish clashing against jank, which made my experience all the more beguiling. How could a team this evidently talented drop the ball in some very key areas? Was this the result of a rocky dev cycle, perhaps the main reason why Kim and Choe both splintered after this game and brought different friends to different companies? Just as the moth feeds upon the flower, this experiment in translating arcade and console play to monitor and keyboard was just one more casualty that would repeat itself, followed by other small studios making action/platformer/etc. debuts before working towards beefier software.

Lychnis drew in crowds of malnourished PC gamers with its heavy amount of smooth vertical and horizontal scrolling, harkening to the likes of Sonic and other mascots. (There's even a porcupine baddie early in the game which feels like an ode to SEGA's superstar.) Its premise also has a cute young adult appeal, with you choosing either the wall-jumping titular character in knight's armor, or his friend Iris, a cheeky mage with a very useful double jump and projectiles. Either way, we're off to defeat an evil sorcerer hell-bent on reviving ancient powers to conquer the continent of Laurasia. The worlds we visit reflect that treacherous journey away from home, starting in verdant fields, hills, and skies before ending within Sakiski's dread citadel full of traps and monsters. Anyone who's played a classic Ys story should recognize the similarities, and parts of this adventure brought Adol's trials in Esteria or Felghana to mind.

However, this still most resembles a platformer more like Wardner, Rastan, or the aforementioned Mario titles on Super Nintendo. The game loop consists of reaching each level's crystalline endpoint and then visiting the shop if you've acquired the requisite keycard. Pro tip: raise max continues to 5 and lives to 7. Lychnis doesn't ramp up its difficult right from the get-go, but World 1-3 presents the first big challenge, an arduous auto-scrolling climb from trees to clouds with no checkpoints whatsoever. I couldn't help but feel the designers struggled to decide if this would focus on 1CC play or heavy continues usage. There's a couple levels, both auto-scrollers, placed around mid-game which are very clearly meant to force Game Overs upon unsuspecting players who aren't concentrating and memorizing. Your lack of control per jump makes Iris the easy pick just for having more opportunities to correct trajectory, both for gaps and to keep distance from enemies and their attacks. Progressing through stages rarely feels that confusing in a navigation sense, but most present puzzles of varying efficacy which can impede you and lead to retries. With no saves or passwords, nor ways to gain continues or lives through high scores, this journey's very unforgiving for most today.

Thankfully there's only one case of multiple dubiously engineered levels in a row, unfortunately coming a bit early with 2-2 and 2-3. The former's just outright broken unless you play a certain way, having to time your attacks and positioning upon each set of mine-carts as tons of obstacles threaten to knock you off. Someone in the office must have had a penchant for auto-scrollers, which live up to their foul reputation whenever they appear here. (I'll cut 3-3 some slack for having a more unique combat-heavy approach, plus being a lot shorter, but it's still a waste of space vs. a fully fleshed-out exploratory jaunt across the seas.) 2-3, meanwhile, shows how masochistic Lychnis can get, with many blind jumps, sudden bursts of enemies from off-screen knocking you down bottomless pits, and lava eruptions casting extra hazards down upon you for insult to injury. Contrast this with the demanding but far fairer platforming gauntlets in 2-1, 3-2, and all of World 4's surprisingly non-slippery icy reaches. "All over the place" describes the content on offer here, and I could hardly accuse Artcraft of, um, crafting a boring or indistinct trip across these biomes.

What Lychnis does excel at is its pacing and means of livening up potential filler via an upgrades system. Thoroughly exploring stages, and clearing as many enemies and chests as you can find, builds up your coffers over time. Survive long enough, farm those 1-Ups and gold sacks, and eventually those top-tier weapons and armor are affordable, plus the ever nifty elixir that refills your life once between shops. This learn-die-hoard-buy loop takes most of the sting away from otherwise mirthless runs through these worlds, but is unfortunately tied to the game's most egregious failing: its one and only boss fight. Ever wonder how the rock-paper-scissors encounters from classic Alex Kidd games could get worse?! This game manages it by basically having you play slots with the big bad, where one either matches all symbols for damage or fails and takes a beating themselves. Only having the best gear makes this climactic moment reliably winnable, which I think is a step too far towards punishing all players, even the most skilled. It sucks because I kind of enjoy 5-3 right before, a very dungeon crawler-esque finale with lots of mooks to juggle and careful resource management. The ending sequence itself is as nice and triumphant as I'd expect, but what came right before was a killjoy.

I've shown a lot of mixed feelings for this so far, yet I still would recommend Lychnis to any classic 2D bump-and-jump aficionados who can appreciate the history behind this Frankenstein. For all my misgivings, it still felt to satisfying to learn the ins and outs, optimize my times, and somewhat put to rest that sorcerer's curse of not having played many Korean PC games. Of course, both Softmax and its offshoot Gravity would soon well surpass this impressive but unready foundation, whose success led to the frenetic sci-fi blockbuster Antman 2 and idiosyncratic pre-StarCraft strategy faire like Panthalassa. I suspect this thorny rose among Korean classics won't rank with many others waiting in my backlog, not that it's done a disservice by those later games fulfilling Artcraft's vision and promises of DOS-/Windows-era software finally reaching the mainstream. The biggest shame is how fragile that region's games industry has always been, from early dalliances with bootlegs and largely text-driven titles to the market constricting massively towards MMOs and other stuff built only for Internet cafes (no shade to those, though).

Just about the biggest advantage these classic Korean floppy and CD releases have over, say, anything for PC-98 is their ease of emulation. Lychnis remains abandonware, the result of its publisher not caring to re-release or even remaster this for Steam and other distributors. Free downloads are just a hop and a skip away, though none of these games have anything like the GOG treatment. With recent news of Project EGG bringing classic Japanese PC games to Switch, though, perhaps there's a chance that other East Asian gems and curiosities can find a place in the sun once more. Well, I can dream.

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Mar. 14 - 20, 2023 LATE

1980

tim rogers voice I Was a Sierra On-Line Poser smashes keyboard on stage and plays foosball with the keycaps

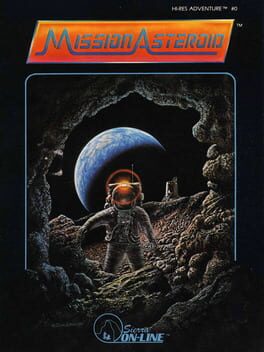

Like many others who love media history but struggle to get into or make time for certain parts of it, the formative parser-driven adventure games like Wander, Colossal Cave Adventure, and Sierra On-Line's classics like Mystery House have eluded me. But I'm also guilty of just not going for them like a hunter chases flock, or a prospector dives for gold. To have this apathy, despite knowing pretty much all these games are easily playable on Internet Archive, ate at me until recently. Something's clicked—probably just the satisfaction of completing Myst last month after years of never clearing the first island. But that's enough to get me committed to trying these ramshackle first attempts at conjuring immersive worlds on the earliest home computer platforms.

Mission Asteroid had a simple, er, mission: introduce any and all possible Apple II users to the graphic text adventure. Roberta Williams knew this didn't have to be as intricate as her Agatha Christie-esque first game, nor as fanciful as The Wizard and the Princess. A solid, pulp-y "save the Earth!" story could get you used to the studio's text parser, thinking up valid verb combinations, and managing your time and patience wisely. No matter how much this game continues to age like an indescribable beverage, it still fulfills those criteria. That's a nice way of saying this 1980 release had much less bullshit puzzling and navigation than its peers.

What the Williams duo would have called "simple" or "entry-level" then is considered hard to parse today dodges tomatoes after that pun. You've got the usual N-S-E-W compass commands, sure, but also instances of having to enter door rather than just go north through it. The two-word restriction on your interactions becomes painfully clear when trying to do something as straightforward as insert a floppy disk into the mission HQ Apple II. You type take disk, carriage return, and then insert disk (repeat), only for the game to ask where you're inserting this thing. There's no death branch here if you specify the wrong target or anything, just needless busywork compounded by the parser system.

Yet, for all the grief these simplistic parsers give me, there's still the fun of tinkering with what hidden-in-plain-sight options you can type in. All the gizmos in your space rocket can either doom you or take you on a disorienting ride through Earth orbit, controlled only by your type-in commands. Wandering the asteroid itself becomes a tense adventure as you likely know from harsh experience that the air supply's time-limited. Once the game lifts its tutorializing gaze from you, Mission Asteroid feels like an organic interplay between you, the reader asking questions, and the ghost of a game master hiding in the machine. It's easier now to see how Roberta, Ken, and others who'd soon join On-Line Systems could champion this genre framework.

Obviously there's not much to look at in this now, with its rudimentary VersaWriter drawings and lack of sound design. At the end of the day, most of the puzzles are either too simple to satisfy or convoluted enough to irritate me a bit too much. But I can gladly say that Mission Asteroid's an easier way to start playing turn-of-the-'80s graphic text stories than I've been told. It gets you into the necessary frame of mind with relatively little condescending scenarios or design language. The truly brutal riddles and cat's cradles of contemporary text adventures are reduced in scope, tightening up the pace. One gets to have a just-filling-enough time with the genre here before it overstays its welcome, either by avoiding a glut of bad ends or treating the player's time with more respect. I sense and can only speculate that Roberta's need to finish this romp for the holidays, capitalizing on Mystery House's success, left less room for potentially harmful experiments or indulgence.

So it's the definition of mid, yet I can't hold that against this game in retrospect. There's much worse one could try from that era, ranging from Scott Adams' pioneering all-text enigmas to their slapdash imitators on TRS-80 or Commodore PET (take your pick of PC cheaper than the Apple ][+). Given how Mission Asteroid itself avoids some of the amateur mistakes in Mystery House I hear about, I'm not content slapping this with a 2-star and calling it there. Whether or not it's a labor of love on par with Sierra On-Line's adventures soon to come, this little ditty of a day's work blowing up an asteroid punches above its weight class where it counts. Some higher being oughta know we got more than we asked for when Michael Bay's people adapted the premise almost two decades later. Keep it simple, Sierra!

Like many others who love media history but struggle to get into or make time for certain parts of it, the formative parser-driven adventure games like Wander, Colossal Cave Adventure, and Sierra On-Line's classics like Mystery House have eluded me. But I'm also guilty of just not going for them like a hunter chases flock, or a prospector dives for gold. To have this apathy, despite knowing pretty much all these games are easily playable on Internet Archive, ate at me until recently. Something's clicked—probably just the satisfaction of completing Myst last month after years of never clearing the first island. But that's enough to get me committed to trying these ramshackle first attempts at conjuring immersive worlds on the earliest home computer platforms.

Mission Asteroid had a simple, er, mission: introduce any and all possible Apple II users to the graphic text adventure. Roberta Williams knew this didn't have to be as intricate as her Agatha Christie-esque first game, nor as fanciful as The Wizard and the Princess. A solid, pulp-y "save the Earth!" story could get you used to the studio's text parser, thinking up valid verb combinations, and managing your time and patience wisely. No matter how much this game continues to age like an indescribable beverage, it still fulfills those criteria. That's a nice way of saying this 1980 release had much less bullshit puzzling and navigation than its peers.

What the Williams duo would have called "simple" or "entry-level" then is considered hard to parse today dodges tomatoes after that pun. You've got the usual N-S-E-W compass commands, sure, but also instances of having to enter door rather than just go north through it. The two-word restriction on your interactions becomes painfully clear when trying to do something as straightforward as insert a floppy disk into the mission HQ Apple II. You type take disk, carriage return, and then insert disk (repeat), only for the game to ask where you're inserting this thing. There's no death branch here if you specify the wrong target or anything, just needless busywork compounded by the parser system.

Yet, for all the grief these simplistic parsers give me, there's still the fun of tinkering with what hidden-in-plain-sight options you can type in. All the gizmos in your space rocket can either doom you or take you on a disorienting ride through Earth orbit, controlled only by your type-in commands. Wandering the asteroid itself becomes a tense adventure as you likely know from harsh experience that the air supply's time-limited. Once the game lifts its tutorializing gaze from you, Mission Asteroid feels like an organic interplay between you, the reader asking questions, and the ghost of a game master hiding in the machine. It's easier now to see how Roberta, Ken, and others who'd soon join On-Line Systems could champion this genre framework.

Obviously there's not much to look at in this now, with its rudimentary VersaWriter drawings and lack of sound design. At the end of the day, most of the puzzles are either too simple to satisfy or convoluted enough to irritate me a bit too much. But I can gladly say that Mission Asteroid's an easier way to start playing turn-of-the-'80s graphic text stories than I've been told. It gets you into the necessary frame of mind with relatively little condescending scenarios or design language. The truly brutal riddles and cat's cradles of contemporary text adventures are reduced in scope, tightening up the pace. One gets to have a just-filling-enough time with the genre here before it overstays its welcome, either by avoiding a glut of bad ends or treating the player's time with more respect. I sense and can only speculate that Roberta's need to finish this romp for the holidays, capitalizing on Mystery House's success, left less room for potentially harmful experiments or indulgence.

So it's the definition of mid, yet I can't hold that against this game in retrospect. There's much worse one could try from that era, ranging from Scott Adams' pioneering all-text enigmas to their slapdash imitators on TRS-80 or Commodore PET (take your pick of PC cheaper than the Apple ][+). Given how Mission Asteroid itself avoids some of the amateur mistakes in Mystery House I hear about, I'm not content slapping this with a 2-star and calling it there. Whether or not it's a labor of love on par with Sierra On-Line's adventures soon to come, this little ditty of a day's work blowing up an asteroid punches above its weight class where it counts. Some higher being oughta know we got more than we asked for when Michael Bay's people adapted the premise almost two decades later. Keep it simple, Sierra!

2014

funny how the one MOBA I've ever played only caught my eye because the devs conceived it as a modernized Herzog Zwei, except that's something they kinda got away from over time...

I played this back during its alpha phase, before Ubisoft brought it to consoles. Nothing tells me what pushed these guys into trying silly things like a VR port when they could have changed up the core modes, or anything to make this stand out from the crowd. Granted, someone more active in the beta and release periods would know more about whether or not this ended up and remained fun to play. This was also the only time I ever played a Chrome Store game, something the IGDB/Backloggd page won't tell you about its origins. That period of web-based free-to-play games seems to have waned, or just folded into the background as everyone and their mother does that stuff via Roblox instead. Funny how these trends come and go, only as prescient or permanent as the market and its manipulators demand.

Basically, imagine the aforementioned Tecno Soft RTS for Mega Drive, just with distinct factions and heroes + the usual mess of loadout management and heavy micro associated with this genre. Something tells me that I gravitated towards AirMech to fill the Battle.net gap in my soul, not having a Windows PC good enough for StarCraft II and having no idea (at the time) how to get classic Blizzard online games going. The ease of matching with relatively equally skilled players early on helped here, as I generally won and lost games in that desirable tug-of-war pattern you'd hope for. Quickly managing unit groups, keeping up pressure in lanes and the neat lil' alleys on each map, all while doing plenty of your own shooting and distraction using the hero unit-meets-cursor...this had a lot going for it.

There's a bit of a trend with very beloved and played free-to-play classics getting, erm, "classic" fan remasters years down the line, e.g. RuneScape or Team Fortress 2. But because AirMech was always closed source and never had that level of traction (some would argue distinction in this crowded genre), there's no way for me to revisit the pre-buyout era and place my memories on trial. What I've seen from AirMech Arena, meanwhile, seems more soulless and bereft of unique or meaningful mechanics and community. It's very easy to just play Herzog Zwei online via emulators or the SEGA Ages release on Switch, too, and that's held up both in legacy and playability. So the niche this web-MOBA/-RTS experiment tried to address is now flush with alternatives, let alone the origins they all point to.

Maybe this just sounds like excuses for me not to download the damn thing and give it a whirl. All I know is this led me to playing Caveman 2 Cosmos and saving up more for my 3DS library at the time. The beta didn't exactly develop that fast, and when it did, the general concept and game loop started favoring ride-or-die players over those like me who just wanted to occasionally hop in and have a blast. Balancing for both invested regulars and casual fans is a bitch and a half, yet I also can't imagine this would have been fun if imbalanced towards skilled folks constantly redefining the meta. The extensive mod-ability and "anything goes" attitude of classic Battle.net games definitely wasn't and isn't a thing for AirMech, nor do I suspect the developers ever wanted that. If it's a focused, overly polished RTS-MOBA you're looking for, I'm sure there's worse out there, but this no longer has that scrappy, Herzog-like simplicity that I crave.

The premise still has a lot of potential, even if Carbon Games seems content with where they've brought the series so far. I'd love to have a more story-focused, singleplayer-friendly variation, something which spiritual predecessors like NetStorm surely could have used. Until then, eh. This one's just here, sitting in the back of my community college neurons, taunting me with what could have been.

I played this back during its alpha phase, before Ubisoft brought it to consoles. Nothing tells me what pushed these guys into trying silly things like a VR port when they could have changed up the core modes, or anything to make this stand out from the crowd. Granted, someone more active in the beta and release periods would know more about whether or not this ended up and remained fun to play. This was also the only time I ever played a Chrome Store game, something the IGDB/Backloggd page won't tell you about its origins. That period of web-based free-to-play games seems to have waned, or just folded into the background as everyone and their mother does that stuff via Roblox instead. Funny how these trends come and go, only as prescient or permanent as the market and its manipulators demand.

Basically, imagine the aforementioned Tecno Soft RTS for Mega Drive, just with distinct factions and heroes + the usual mess of loadout management and heavy micro associated with this genre. Something tells me that I gravitated towards AirMech to fill the Battle.net gap in my soul, not having a Windows PC good enough for StarCraft II and having no idea (at the time) how to get classic Blizzard online games going. The ease of matching with relatively equally skilled players early on helped here, as I generally won and lost games in that desirable tug-of-war pattern you'd hope for. Quickly managing unit groups, keeping up pressure in lanes and the neat lil' alleys on each map, all while doing plenty of your own shooting and distraction using the hero unit-meets-cursor...this had a lot going for it.

There's a bit of a trend with very beloved and played free-to-play classics getting, erm, "classic" fan remasters years down the line, e.g. RuneScape or Team Fortress 2. But because AirMech was always closed source and never had that level of traction (some would argue distinction in this crowded genre), there's no way for me to revisit the pre-buyout era and place my memories on trial. What I've seen from AirMech Arena, meanwhile, seems more soulless and bereft of unique or meaningful mechanics and community. It's very easy to just play Herzog Zwei online via emulators or the SEGA Ages release on Switch, too, and that's held up both in legacy and playability. So the niche this web-MOBA/-RTS experiment tried to address is now flush with alternatives, let alone the origins they all point to.

Maybe this just sounds like excuses for me not to download the damn thing and give it a whirl. All I know is this led me to playing Caveman 2 Cosmos and saving up more for my 3DS library at the time. The beta didn't exactly develop that fast, and when it did, the general concept and game loop started favoring ride-or-die players over those like me who just wanted to occasionally hop in and have a blast. Balancing for both invested regulars and casual fans is a bitch and a half, yet I also can't imagine this would have been fun if imbalanced towards skilled folks constantly redefining the meta. The extensive mod-ability and "anything goes" attitude of classic Battle.net games definitely wasn't and isn't a thing for AirMech, nor do I suspect the developers ever wanted that. If it's a focused, overly polished RTS-MOBA you're looking for, I'm sure there's worse out there, but this no longer has that scrappy, Herzog-like simplicity that I crave.

The premise still has a lot of potential, even if Carbon Games seems content with where they've brought the series so far. I'd love to have a more story-focused, singleplayer-friendly variation, something which spiritual predecessors like NetStorm surely could have used. Until then, eh. This one's just here, sitting in the back of my community college neurons, taunting me with what could have been.

1983

WOW! YOU LOSE!! (by playing the downgraded Famicom port of a 1983 game?)

Bokosuka Wars was to Japan's real-time sim/strategy genres what Utopia, Stonkers, & Cytron Masters were to '80s Western PC RTSes. I'd argue this game was more important than them simply for its influence on Tecno Soft's Herzog series, which itself inspired Westwood developers who'd later make the seminal Dune II. That's a lot of words to say this isn't some throwaway footnote in the Famicom library. Japanese PC game conversions to Nintendo's machine were a big event in those early years, and Bokosuka Wars had a genuine wow factor that still matters.

ASCII published this lone creation by Koji Sumii (today a traditional craftsman & puppeteer) on cassette for Sharp's X1 micro-computer back in '83 to much acclaim. It got an expansion/sequel the year later and ports to other PCs before reaching the Famicom. Despite a modern sequel being well-received, the Nintendo rendition has gone down in kusoge history. After all, why try & play this experimental proto-RTS on its own terms when you can bumble into an early wipe & laugh at the game over screen? /s

Context aside, I still have a lot of fun with the PC original, which combines basic real-time strategy mechanics with a light RNG layer & simple to understand progression. Unlike the Famicom port where you start with no soldiers at all, the X1 original gives you a big starting squad. This lets you get used to the controls & your units' frailty before you dive headfirst into the front-lines. Learning how to make new units from trees, plus how to quickly reposition grunts in front of you to do battles, becomes second nature after a while. I wouldn't call this an easy game, but it's hardly as ill-designed or inscrutable as retro discussions make it out to be.

I'd mainly recommend playing this if you're interested in the RTS genre's history or would enjoy a simple, sometimes frustrating but ultimately compelling arcade wargame. The X1 version's not too hard to find out in the digital wilderness, but I wish it was officially accessible via a modern remake or even through Project EGG for PC users. It's an important & distinctive piece of software which paved the way not just for Herzog (Zwei) & Dune II, but other oddities like Kure Software's Silver Ghost & First Queen series.

Bokosuka Wars was to Japan's real-time sim/strategy genres what Utopia, Stonkers, & Cytron Masters were to '80s Western PC RTSes. I'd argue this game was more important than them simply for its influence on Tecno Soft's Herzog series, which itself inspired Westwood developers who'd later make the seminal Dune II. That's a lot of words to say this isn't some throwaway footnote in the Famicom library. Japanese PC game conversions to Nintendo's machine were a big event in those early years, and Bokosuka Wars had a genuine wow factor that still matters.

ASCII published this lone creation by Koji Sumii (today a traditional craftsman & puppeteer) on cassette for Sharp's X1 micro-computer back in '83 to much acclaim. It got an expansion/sequel the year later and ports to other PCs before reaching the Famicom. Despite a modern sequel being well-received, the Nintendo rendition has gone down in kusoge history. After all, why try & play this experimental proto-RTS on its own terms when you can bumble into an early wipe & laugh at the game over screen? /s

Context aside, I still have a lot of fun with the PC original, which combines basic real-time strategy mechanics with a light RNG layer & simple to understand progression. Unlike the Famicom port where you start with no soldiers at all, the X1 original gives you a big starting squad. This lets you get used to the controls & your units' frailty before you dive headfirst into the front-lines. Learning how to make new units from trees, plus how to quickly reposition grunts in front of you to do battles, becomes second nature after a while. I wouldn't call this an easy game, but it's hardly as ill-designed or inscrutable as retro discussions make it out to be.

I'd mainly recommend playing this if you're interested in the RTS genre's history or would enjoy a simple, sometimes frustrating but ultimately compelling arcade wargame. The X1 version's not too hard to find out in the digital wilderness, but I wish it was officially accessible via a modern remake or even through Project EGG for PC users. It's an important & distinctive piece of software which paved the way not just for Herzog (Zwei) & Dune II, but other oddities like Kure Software's Silver Ghost & First Queen series.

2003

Credit where it's due: at least the Game Boy Camera and SEGA's DreamEye got treated with enough dignity to never suffer a minigame collection this lame.

More credit goes to London Studio for injecting some much-needed, if dated amount of personality where it counts. I'll always fondly remember unpacking this honestly not terrible webcam (Logitech wasn't much better in '03), then loading into the cheeky, very post-Psygnosis tutorial movie explaining how to use the peripheral. Watching what might as well be the queen mother and her clones dancing to stock library disco as the Stanley Parable narrator goodbye-s you is still surreal. I wish the game itself had as much family-friendly anarchy. Part of me wants to argue the inconsistent art direction between minigames brings this closer to WarioWare or a modern game jam, but it's just not there.

With 12 minigames of varying quality on offer, Sony's making a go at matching its competitors in silly gimmickry. A good chunk of the experience revolves around variations on whack-a-mole, or something like those Moorhuhn (Crazy Chicken) shovelware titles you see every now and then. This whole idea of pairing a novel, limited but intriguing add-on console toy with what amounts to a prototype Carnival Games worked at the time. The folks & I had a solid time looking stupid in front of the TV, though my sister stuck mostly to our metal DDR pad since those games had far more substance. Little did we know this would have us wibblin' and wobblin' in the living room some years later—that was Wii Sports, though, which remains far more replayable in 2023.

EyeToy Play is fun enough for what it is, a serviceable pack-in game which took the safe route with proving that this idea could even work. Nintendo's aforementioned handheld lens toy has somehow managed to age better by dint of offering a uniquely lo-fi experience, though. Going from harsh but exotic monochrome games and photo printing to the blurry, often out-of-focus mess EyeToy provides seems a bit underwhelming nowadays. What I really lament, though, is the C-rate Y2K aesthetic dominating this collection. (Half of the game looks like it's recycling unused Psybadek concepts, mashing them up with Gorillaz and other post-Y2K intercontinental mascot designs.) It just reminds me too much of when these developers, a mix of ex-Psygnosis fellas and The Getaway's team, had more creative projects to work on.

Again, this isn't a strictly bad game. Most minigames work properly with the EyeToy in most room settings, and it's a bit amusing to wave your arms around, a kind of bastardized ParaPara Paradise or Samba de Amigo for the new era. Just temper your expectations if you collect one of these square, googly things and stick this in your PS2. I'd personally rather play SEGA Superstars if only for the IP variety and actual Samba de Amigo experience. However, the lack of ambition and increasingly quaint presentation behind this pack-in was kind of the point. If it was too good a free disc to keep playing, would you have bought all those other EyeToy games coming later? Consider how Nintendo fell into that trap later, with Wii Sports & Play offering enough for most owners to just skip out on following minigame collections (or settle for the bargain bin equivalents).

See, this is exactly what Thursday does to an oldhead like me. I get vaguely nostalgic thoughts about what passed muster for party night amusement at the end of elementary school, and then I think harder about what this was actually like. Youngsters have it so much easier in these social media dog days. EyeToy: Play was the offline TikTok dance simulator of its day, cheaper than a ParaPara cab every weekend but not much more advanced than some plastic maracas. Games like this fall through the cracks of half-remembered cringe and convenient historic amnesia—some would say for the better. I just feel sorry for all the UK devs Sony chopped into teams like London Studio, who then had to take any mid project they could get by their corporate sponsor. tl;dr Where the hell's the Wipeout minigame in this set?!

More credit goes to London Studio for injecting some much-needed, if dated amount of personality where it counts. I'll always fondly remember unpacking this honestly not terrible webcam (Logitech wasn't much better in '03), then loading into the cheeky, very post-Psygnosis tutorial movie explaining how to use the peripheral. Watching what might as well be the queen mother and her clones dancing to stock library disco as the Stanley Parable narrator goodbye-s you is still surreal. I wish the game itself had as much family-friendly anarchy. Part of me wants to argue the inconsistent art direction between minigames brings this closer to WarioWare or a modern game jam, but it's just not there.

With 12 minigames of varying quality on offer, Sony's making a go at matching its competitors in silly gimmickry. A good chunk of the experience revolves around variations on whack-a-mole, or something like those Moorhuhn (Crazy Chicken) shovelware titles you see every now and then. This whole idea of pairing a novel, limited but intriguing add-on console toy with what amounts to a prototype Carnival Games worked at the time. The folks & I had a solid time looking stupid in front of the TV, though my sister stuck mostly to our metal DDR pad since those games had far more substance. Little did we know this would have us wibblin' and wobblin' in the living room some years later—that was Wii Sports, though, which remains far more replayable in 2023.

EyeToy Play is fun enough for what it is, a serviceable pack-in game which took the safe route with proving that this idea could even work. Nintendo's aforementioned handheld lens toy has somehow managed to age better by dint of offering a uniquely lo-fi experience, though. Going from harsh but exotic monochrome games and photo printing to the blurry, often out-of-focus mess EyeToy provides seems a bit underwhelming nowadays. What I really lament, though, is the C-rate Y2K aesthetic dominating this collection. (Half of the game looks like it's recycling unused Psybadek concepts, mashing them up with Gorillaz and other post-Y2K intercontinental mascot designs.) It just reminds me too much of when these developers, a mix of ex-Psygnosis fellas and The Getaway's team, had more creative projects to work on.

Again, this isn't a strictly bad game. Most minigames work properly with the EyeToy in most room settings, and it's a bit amusing to wave your arms around, a kind of bastardized ParaPara Paradise or Samba de Amigo for the new era. Just temper your expectations if you collect one of these square, googly things and stick this in your PS2. I'd personally rather play SEGA Superstars if only for the IP variety and actual Samba de Amigo experience. However, the lack of ambition and increasingly quaint presentation behind this pack-in was kind of the point. If it was too good a free disc to keep playing, would you have bought all those other EyeToy games coming later? Consider how Nintendo fell into that trap later, with Wii Sports & Play offering enough for most owners to just skip out on following minigame collections (or settle for the bargain bin equivalents).

See, this is exactly what Thursday does to an oldhead like me. I get vaguely nostalgic thoughts about what passed muster for party night amusement at the end of elementary school, and then I think harder about what this was actually like. Youngsters have it so much easier in these social media dog days. EyeToy: Play was the offline TikTok dance simulator of its day, cheaper than a ParaPara cab every weekend but not much more advanced than some plastic maracas. Games like this fall through the cracks of half-remembered cringe and convenient historic amnesia—some would say for the better. I just feel sorry for all the UK devs Sony chopped into teams like London Studio, who then had to take any mid project they could get by their corporate sponsor. tl;dr Where the hell's the Wipeout minigame in this set?!

PoPoLoCrops! FarmPG cuteness from start to finish. Add a tad of Ghibli-esque darkness on the fringes, perhaps. It's an odd way to start my PoPoLoCrois journey, but far from an unfitting one. I had worries about how well the Story of Seasons systems would integrate with what's otherwise a regular series entry, spinoff status aside. So I'm glad to say that you neither have to rely on farming too much, nor simply ignore it for other items & buffs. Good QoL features & menu design helps out here, but also the strong pacing elsewhere.

The whole premise of a foreign country's purported leaders being parasitic conquerors of both your home & theirs gets things rolling. You go from a fun if slight celebration of Pietro's accomplishments to date (something I'll be more familiar with later) to getting marooned in a strange land, fighting on the backfoot. Early dungeons & world traversal hardly take much time. This definitely feels more like a JRPG for fans of towns & characters, less so encounters. Much of the game loop teeters between quick trips to your ranch (economy) & engaging with story areas and events.

Sorry Pokemon, but this adventure has the superior Galar(iland) region. Epics & Marvelous do a stellar job of balancing the new cast, populace, & worldbuilding with returning parts of the PoPoLoCrois world. I had such a smile on my face when finally getting to fight alongside a distraught GamiGami trying to regain his big bad status. Or how about realizing who the conspicuous wolf at your side really is? (An old friend indeed!) All the towns are fun to explore & talk your way through, and I certainly can't recall any bad dungeons...just some less than interesting ones.

While the farming & story elements have a satisfying synergy, the combat here is almost as standard as it gets for a modern handheld JRPG. Not a bad thing, but it's hard for me to get excited about this when something like The Alliance Alive arrived shortly after on this system. The most notable aspect is the grid-based movement & diversity of AoE/position-based abilities on offer. It's mostly harmless, and the difficulty balance is solid. Just don't get into this for the sake of challenging battles. You can mess with the optional ranch battles for a bit more loot & leveling, but I never finished that side-mode.

I hope this gets a proper remaster at some point. It's way more PoPoLoCrois than Story of Seasons, for the better I'd argue. Among XSEED's other localizations, this remains one of the most unsung, and changing that would be awesome.

The whole premise of a foreign country's purported leaders being parasitic conquerors of both your home & theirs gets things rolling. You go from a fun if slight celebration of Pietro's accomplishments to date (something I'll be more familiar with later) to getting marooned in a strange land, fighting on the backfoot. Early dungeons & world traversal hardly take much time. This definitely feels more like a JRPG for fans of towns & characters, less so encounters. Much of the game loop teeters between quick trips to your ranch (economy) & engaging with story areas and events.

Sorry Pokemon, but this adventure has the superior Galar(iland) region. Epics & Marvelous do a stellar job of balancing the new cast, populace, & worldbuilding with returning parts of the PoPoLoCrois world. I had such a smile on my face when finally getting to fight alongside a distraught GamiGami trying to regain his big bad status. Or how about realizing who the conspicuous wolf at your side really is? (An old friend indeed!) All the towns are fun to explore & talk your way through, and I certainly can't recall any bad dungeons...just some less than interesting ones.

While the farming & story elements have a satisfying synergy, the combat here is almost as standard as it gets for a modern handheld JRPG. Not a bad thing, but it's hard for me to get excited about this when something like The Alliance Alive arrived shortly after on this system. The most notable aspect is the grid-based movement & diversity of AoE/position-based abilities on offer. It's mostly harmless, and the difficulty balance is solid. Just don't get into this for the sake of challenging battles. You can mess with the optional ranch battles for a bit more loot & leveling, but I never finished that side-mode.

I hope this gets a proper remaster at some point. It's way more PoPoLoCrois than Story of Seasons, for the better I'd argue. Among XSEED's other localizations, this remains one of the most unsung, and changing that would be awesome.

2000

Welcome to driving schools, pirate ships, dragon coasters...the stuff plastic dreams are made of. Too bad you have to run the place.

Maybe it's not so bad—in fact, it's comically easy. You do have a semblance of time limits in the later missions, but building and maintaining parks is very straightforward. I wish the developers hadn't missed the boat on RollerCoaster Tycoon's additions to the park tycoon format; this one's much closer to Theme Park. While I don't have anything against Bullfrog's game, Chris Sawyer had quickly advanced the genre's complexity without sacrificing accessibility for new players. Most importantly, RCT & its ilk were much more about creatively designing & planning your realm, not just working with repetitive prefabs.

This makes Legoland a solid enough Windows 9x tycoon romp, but a rather shallow one too. It's fine when you're starting with tutorials offering limited attractions, scenery, and staff to manage, yet it doesn't ramp up much beyond that. A lot of the budget instead went to making as sleek & colorful a package as Lego Media could muster, with memorable FMV movies and the like. Music & sound design's also pleasant on the ears, so I can't complain there. As a kid, this seemed like the coolest game, a better structured alternative to Lego Creator that also let me feel like I was at the parks.

Assuming you can get it running on your PC (I fear for Steam Deck users...), Legoland's a reliably entertaining example of how diverse Lego games once were. Its controls & QoL features are definitely dated, but you're rarely if ever challenged to the point that you'll need modern streamlining. (Not that I'd ever complain about folks modding this game to a higher tier than it currently sits in!) Temper you expectations, though. The repetition, somewhat low amount of content, & constrained potential for sandbox play makes this more of a one-and-done for me.

P.S. The game's spokesperson & tutorial guy wouldn't last a day on social media. What a clown.

Maybe it's not so bad—in fact, it's comically easy. You do have a semblance of time limits in the later missions, but building and maintaining parks is very straightforward. I wish the developers hadn't missed the boat on RollerCoaster Tycoon's additions to the park tycoon format; this one's much closer to Theme Park. While I don't have anything against Bullfrog's game, Chris Sawyer had quickly advanced the genre's complexity without sacrificing accessibility for new players. Most importantly, RCT & its ilk were much more about creatively designing & planning your realm, not just working with repetitive prefabs.

This makes Legoland a solid enough Windows 9x tycoon romp, but a rather shallow one too. It's fine when you're starting with tutorials offering limited attractions, scenery, and staff to manage, yet it doesn't ramp up much beyond that. A lot of the budget instead went to making as sleek & colorful a package as Lego Media could muster, with memorable FMV movies and the like. Music & sound design's also pleasant on the ears, so I can't complain there. As a kid, this seemed like the coolest game, a better structured alternative to Lego Creator that also let me feel like I was at the parks.

Assuming you can get it running on your PC (I fear for Steam Deck users...), Legoland's a reliably entertaining example of how diverse Lego games once were. Its controls & QoL features are definitely dated, but you're rarely if ever challenged to the point that you'll need modern streamlining. (Not that I'd ever complain about folks modding this game to a higher tier than it currently sits in!) Temper you expectations, though. The repetition, somewhat low amount of content, & constrained potential for sandbox play makes this more of a one-and-done for me.

P.S. The game's spokesperson & tutorial guy wouldn't last a day on social media. What a clown.

2001

For the people, it was just another exhilarating day, punching and rocketing through a deformed, deranged B-movie. For a decorated Pangea Software, this was maybe their most passionate, prestigious creation. Brian Greenstone and his frequent co-developers had the notion to refine their previous Macintosh action platformers, Nanosaur and Bugdom, into nostalgia for cheesy, laughable Hollywood science fantasy films. As the 2000s got started, this studio wasn't as pressured to prove the PowerPC Mac's polygonal potential, but Otto Matic still fits in with its other pack-in game brethren. All that's changed is Greenstone's attention to detail and playability, previously more of a secondary concern. This Flash Gordon reel gone wrong doesn't deviate from the collect-a-thon adventure template of its predecessors, yet it delivers on the promises they'd made but couldn't quite realize. Greenstone had finally delivered; the eponymous hero had arrived in both style and substance.

Players boot into a cosmos of theremins, campy orchestration, big-brained extraterrestrials, provincialUFO bait humans awaiting doom, and this dorky but capable android who kind of resembles Rayman. Start a new game and you're greeted with something rather familiar, yet different: simple keyboard-mouse controls, hostages to rescue, plentiful cartoon violence, and a designer's mean streak hiding in plain sight. The delight's in the details, as Otto has an assortment of weapons and power-ups with which to defeat the alien invaders and warp these humans to safety. It's just as likely you'll fall into a puddle and short-circuit, though, or mistime a long distance jump-jet only to fall into an abyss. What I really liked in even the earliest Pangea soft I've tried, Mighty Mike, is this disarming aesthetic tied closely with such dangers. I hesitate to claim this mix of Ed Wood, Forbidden Planet, and '90s mascot platformers will appeal to everyone (some find it disturbing, let alone off-putting), but it's far from forgettable in a sea of similar titles. It helps that the modern open-source port's as usable as others.

The dichotomy between Otto Matic's importance for modern Mac gaming and its selfish genre reverence isn't lost on me. One wouldn't guess this simple 10-stage, single-sitting affair could offer much more than Pangea's other single-player romps. On top of its release as a bundled app, they turned to Aspyr for pressing and publishing a retail version, followed by the standard Windows ports. Accordingly, the evolution of Greenstone's 3D games always ran in tandem with Apple's revival and continuation of their Y2K-era consumer offerings. His yearly releases demanded either using the most recent new desktop or laptop Macs, or some manner of upgrade for anyone wielding an expandable Power Mac. Fans of Nanosaur already couldn't play it on a 2001 model unless they booted into Mac OS 9, for example, while the likes of Billy Western would arrive a year later solely for Mac OS X. The studio's progress from one-man demo team to purveyor of epoch-defining commercial games feels almost fated.