Cadensia

BACKER

2012

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (18th Apr. – 24th Apr., 2023).

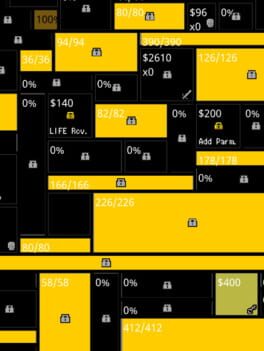

There is something charming about Yoshio Ishī's minimalist style. The Hoshi Saga series proposed micro-puzzles from which silent poetry emerged. A few mouse clicks were enough to explore paper miniatures reminiscent of children's dioramas. The pronounced texture of the washi paper underlines the artificial quality of the puzzles and their ephemeral nature. Parameters goes in a completely opposite direction, as with a much colder concept. Instead of building a sensory and kinetic experience, Ishī boils down the components of dungeon crawlers to their bare essentials, encapsulating exploration, combat and grinding into a minimalist interaction. In some ways, Parameters is an attempt to return to the fundamentals of the genre, but without the ruggedness of the old games.

The progression is intuitive: to increase one's stats, to be able to face the more difficult boxes, it is necessary to gain experience, either by killing enemy blocks or by exploring empty ones. Some are accessible from the start, while others are locked. To open them, the player must use an iron key found on enemies. Parameters flows naturally and, as waverly_khitryy notes, is similar to an idle game in that the number of actions the player can perform in quick succession is limited by an energy bar. After a couple of clicks, the player has to wait for a short time before interacting further with the blocks. The game appears to be a sort of meditation on the dungeon crawler theme, but Parameters offers few subtleties beyond these basic elements. The various resources and statistics affect the progression, but there is no need for the player to devise any kind of strategy.

The order in which the blocks are explored or fought never matters, as a quick gold grind is enough to increase the various stats, bypassing the need for a level-up. This would not be a problem if the title offered some variation in the distribution of the blocks: Parameters, however, is a fixed experience. The board is always the same, with the same numerical values. One might have thought that the arrangement of the blocks was meaningful, that the chests could only be opened after exploring all the adjacent boxes, but this is not the case. Apart from the slight gratification of seeing the numbers increase, the experience is quite mind-numbing. Death is never punishing, as the player slowly regains his life, but it can lead to incompressible downtime. Again, this is not a problem in a meditative experience, but it also encourages the stultifying gold grind to buy equipment, which undermines any semblance of tension.

Parameters can be seen as a good imitation of the dungeon crawler gameplay loop, turning the passive sequences into mild dopamine rushes driven by the desire to complete the grid. But because they are drowned in an overly smoothed-out experience, they become more awkward than anything else, despite the game's brevity. For the rest, the title does not try to pretend to be what it is not: it is indeed a minimalist experience, in every sense of the word.

There is something charming about Yoshio Ishī's minimalist style. The Hoshi Saga series proposed micro-puzzles from which silent poetry emerged. A few mouse clicks were enough to explore paper miniatures reminiscent of children's dioramas. The pronounced texture of the washi paper underlines the artificial quality of the puzzles and their ephemeral nature. Parameters goes in a completely opposite direction, as with a much colder concept. Instead of building a sensory and kinetic experience, Ishī boils down the components of dungeon crawlers to their bare essentials, encapsulating exploration, combat and grinding into a minimalist interaction. In some ways, Parameters is an attempt to return to the fundamentals of the genre, but without the ruggedness of the old games.

The progression is intuitive: to increase one's stats, to be able to face the more difficult boxes, it is necessary to gain experience, either by killing enemy blocks or by exploring empty ones. Some are accessible from the start, while others are locked. To open them, the player must use an iron key found on enemies. Parameters flows naturally and, as waverly_khitryy notes, is similar to an idle game in that the number of actions the player can perform in quick succession is limited by an energy bar. After a couple of clicks, the player has to wait for a short time before interacting further with the blocks. The game appears to be a sort of meditation on the dungeon crawler theme, but Parameters offers few subtleties beyond these basic elements. The various resources and statistics affect the progression, but there is no need for the player to devise any kind of strategy.

The order in which the blocks are explored or fought never matters, as a quick gold grind is enough to increase the various stats, bypassing the need for a level-up. This would not be a problem if the title offered some variation in the distribution of the blocks: Parameters, however, is a fixed experience. The board is always the same, with the same numerical values. One might have thought that the arrangement of the blocks was meaningful, that the chests could only be opened after exploring all the adjacent boxes, but this is not the case. Apart from the slight gratification of seeing the numbers increase, the experience is quite mind-numbing. Death is never punishing, as the player slowly regains his life, but it can lead to incompressible downtime. Again, this is not a problem in a meditative experience, but it also encourages the stultifying gold grind to buy equipment, which undermines any semblance of tension.

Parameters can be seen as a good imitation of the dungeon crawler gameplay loop, turning the passive sequences into mild dopamine rushes driven by the desire to complete the grid. But because they are drowned in an overly smoothed-out experience, they become more awkward than anything else, despite the game's brevity. For the rest, the title does not try to pretend to be what it is not: it is indeed a minimalist experience, in every sense of the word.

2023

'I was Don Quixote of La Mancha, I am now, as I said, Alonso Quixano the Good; and may my repentance and sincerity restore me to the esteem you used to have for me.'

– Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quijote de la Mancha, 1605.

Played with BertKnot.

Heinrich Heine, the last herald of German Romanticism and its gravedigger, was greatly inspired by Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quijote (1605). Just as the character fought against windmills to restore the grandeur of a picaresque chivalry, Heine fought against the established and conservative order. His idealistic passions led him to support the proponents of the French Revolution, but he also cultivated a deep spiritualism. Stirred by his inner paradoxes, Heine found in Don Quijote a way to reconcile his fragmented positions, embracing the biting irony of Cervantes. [1] In Die romantische Schule (1833), he compared the German and French branches of Romanticism in an attempt to identify their characteristics, achievements and shortcomings. In particular, Heine was highly suspicious of the propensity to recapture medieval spirituality, trapping Romanticism in adoration of the past to the detriment of contemporary experiences – found in the revolutionary cycles of the 19th century among others. In Baudelaire's words, what Heine wanted was 'to plunge into the depths of the Unknown and find something new' [2].

Striving for modernity: a proactive and more dynamic gameplay

Heine emphasised the extent to which Cervantes, by abolishing the picaresque tradition, opened a door for the modern novel and its new sensibilities: 'This is what the great poets will always do: they create something new by destroying the old: they never deny without affirming'. The characteristic strength of Don Quijote is that it genuinely celebrates the humanity and complexity of the hidalgo of La Mancha, rather than denying it altogether. Don Quijote's laughter is that of a man who sees his inability to fully live the role he has chosen for himself. The tragicomedy of the novel is born in the acute awareness of someone who knows that he is deceiving himself. Cervantes inaugurates a new tradition that does not completely reject the old, but draws lessons from it to create modernity: what matters is that something new is created. Resident Evil 4 (2023) also attempts to offer a fresh way of experiencing the classic title, which has proved to be one of the most fundamental in video game history and continues to be cited as a significant influence by many modern designers. Unlike Cervantes and all the writers he inspired, from Heine to Faulkner, this project does not manage to break free from the shackles imposed by the franchise, highlighting structural problems that are already apparent or are yet to come.

From the very first minutes, Resident Evil 4 (2023) establishes a much more serious tone and a more dynamic gameplay than its predecessor. These elements can be seen as an expression of the franchise's maturity and an attempt to modernise the title. These changes clearly affect the way the player interacts with the game. Combat sequences feel longer and more intense, becoming real tests of endurance that challenge the player's ability to manoeuvre in the arena and strategically engage the hordes of enemies. Encounters must take into account the new ability to shoot while moving and the greater versatility offered by the knife and its powerful parries. The player must move constantly, both to manage several fronts at once and to create space between Leon and the many enemies; as their grapple has a very high priority and the character's i-frames seem to have been shortened, it is essential to move wisely, as even knife parries cannot solve all situations.

This aggressive gameplay tends to work very well and keeps the player fully engaged while fighting. Some sequences can drag on – particularly towards the end of the game – but there is real enjoyment to be had from using heavy weapons, parrying attacks with the knife and delivering devastating high kicks. However, the title delivers its experience without fanfare when it tries to stick too closely to the source material. Bosses such as El Gigante come across as decent, while others are simply disappointing for want of ideas. Del Lago is vapid, full of archaisms that no longer elicit the same expressions of surprise as they did in 2005. The new gameplay would have encouraged more interaction with the environment; unfortunately, only the barrels are used and a certain visual fatigue can set in. Leon's kicks dominate the fights, and the rare German Supplex is only a tiny breath of fresh air. Because Resident Evil 4 (2023) stubbornly sticks to a very effective but rather simplistic combat formula, it suffers greatly in its later hours: KB0 has gone to great lengths to highlight the repetitive nature of the title, by analysing specific gameplay elements, and it seems superfluous to revisit them. Instead, it is the additions, such as the stealth sequence with the Garrador, that provide the necessary variety in a modernisation project.

Unambitious atmosphere and unflattering melodrama

To continue the Cervantes analogy, Resident Evil 4 (2023) may seem disappointing, taking no risks and offering no ambition for the future. What appear to be design updates to the original title are ultimately nothing more than bland gameplay elements from Resident Evil 5 (2008) and Resident Evil 6 (2012), whose remakes seem obvious given that the formula works commercially for Capcom. Unlike the attempt of Final Fantasy VII Remake (2020), which reinterpreted the original material in a durable way, Resident Evil 4 (2023) feels half-hearted, driven only by a desire to homogenise. This is not to say that the title is unpleasant, but it comes across as a technically accomplished but unexceptional product. The game presents itself as the ultimate version, which was not the case with the previous remakes, but it never manages to replace the original title, whose unique atmosphere cannot be imitated.

Perhaps because the environments are so detailed, silence no longer manages to conjure up its eerie strangeness; there is no room left for the player's imagination, and the first third of the game loses its evocative power. The view of the church in Resident Evil 4 (2023) is a clean gothic shot, but it is particularly plain. The golden light of the sun breaking through the clouds gives the place of worship a dignified and monumental nobility, rather than the tumultuous grime of the original. In 2005, the emphasis was on the cemetery rather than the building: this change of focus is representative of the game's approach, which is a little too forceful in directing the player's gaze. The atmosphere is sanitised by a multitude of details that do not convey anything. The decision to rely on notes to tell a story is an admission of failure by the title, which fails to put its great technical potential at the service of a subtle narration.

Resident Evil 4 (2023) is more serious and explores some of the characters more thoroughly. Krauser's backstory has been changed to make him a more coherent antagonist, but it is Luis Sera who benefits most from the remake's rewrite. Instead of being a superfluous companion, he is more directly involved in the story, as a series of dialogues and notes reveal the mask he wears to hide his embarrassment and guilt. Luis Sera is Don Quijote, whose adventures have lulled his childhood. Just as the hidalgo of La Mancha dreams of fantastic adventures beyond common understanding, Luis Sera succumbs to the sirens of unethical science. Both understand their mistake and try to make amends; they also share an honest laugh that reflects a partially assumed disenchantment. Resident Evil 4 (2023) shows genuine respect for the character, who inspires real sympathy in Leon and Ashley – perhaps a little too much – and whose code of conduct follows that of the picaresque hero. Krauser and Luis's rewrite could have taken the franchise in a new direction, one that looks at what defines humanity through the complex dilemmas it faces. The 'Resident Evil' title has historically pointed in that direction: a more intimate, character-driven horror.

The conservative roots of the series: from one sexualisation to another

Unfortunately, Resident Evil 4 (2023) does not seem to have realised this potential and justifies the rewriting of the characters for the sake of consistency. The only concern was to freshen up the game's narrative by cutting out the implausible passages. For example, Saddler only appears physically at the end of the game, which allowed for the removal of all his theatrical entrances, where he decided to stand in Leon's way but never kill him. Other changes have clearly been made to remove all the paedophile connotations of the original version. Ashley, still in her early twenties, goes from being a teenage girl to a young woman with a mesmerising face who openly plays on her charm. The majority of critics have seen this transformation in a positive light, never stopping to consider the retrograde representation it still constitutes. Is this because they are convinced of the importance of preserving the misogynistic frivolity of the original title? In any case, Ashley remains an objectified character, always driven by the desire to prove her – sexual – worth to Leon. Her teasing posture during the shooting mini-game is a poor choice, especially after the game's strong emphasis on the Illuminados' abhorrent tactility when dealing with her. The perspective of Resident Evil 4 (2023) is eminently perverse, extending far beyond a mere male gaze.

The franchise has always had a problem with its representation of women, relying on the figure of more or less strong women to fulfil male fantasies; what is particularly disappointing about Ashley's treatment is that it is yet another missed opportunity to provide depth to her character – just as Luis and Krauser were given. Instead of a proper treatment, she has simply been melted into a new sexualising archetype, while her function, for the plot and the audience, remains the same. This frustration is reinforced by Genevieve Buechner's convincing voice acting, which underlines the confidence she gradually gains during her adventure with Leon. But this confidence is immediately squandered by the game, which insists on her powerlessness. The section in which she is playable is pleasant and shows a heroine in the making, but she loses her agency extremely quickly, save for rare exceptions. Likewise, despite a veneer of respect, with Leon speaking Spanish once, the title stubbornly sticks to cultural clichés under the guise of humour, boding ill for the Resident Evil 5 remake.

For many people, Resident Evil 4 (2023) is a way to experience a legendary and beloved title after discovering the franchise with the recent remakes, Resident Evil 7 (2017) or Resident Evil Village (2021). They will not be confused, thanks to a grammar similar to the titles released in recent years. Unsurprisingly, many players have praised the game, saying that they understand why the original title is considered so valuable, even though they are only experiencing it through a standardised proxy. There is a certain irony in the fates of the Resident Evil 4 games, both of which, twenty years apart, confirm the franchise's transition into a new direction. In the case of the original, it was certainly a new modernity, whether one liked it or not, that caused the entire industry to adapt to a bold move. The remake is less about pushing the boundaries of the genre and more about obsequiously conforming to established formulas. Resident Evil 4 (2023) is a pleasure to play, because it borrows everything that is pleasing in the current grammar of game design, from combat dynamism to the importance of melee and parries. It all fits together elegantly, exploiting the strengths of the original level design to create a fresh experience. But it is a sterilised one, rejecting any idiosyncrasy, any stylistic boldness, any poetic imperfection. The strong sections generally remain strong, the weaker passages stay that way; the title never plunges into the unknown, never reveals anything new. The only daring thing about Resident Evil 4 (2023) is that it paves the way for the unnecessary remakes of the subsequent titles, with no guarantee that the sexism and racism that run through them will be amended. In the end, Don Quijote was only a misunderstood reference, never a model.

__________

[1] D. van Maelsaeke, ‘The Paradox of Humour: A Comparative Study of ‘Don Quixote’’, in Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, no. 28, 1967, pp. 24-42.

[2] Charles Baudelaire, ‘Le Voyage’, in Les Fleurs du mal, Poulet-Malassis et de Broise, Paris, 1861 : ‘Verse-nous ton poison pour qu'il nous réconforte ! / Nous voulons, tant ce feu nous brûle le cerveau, / Plonger au fond du gouffre, Enfer ou Ciel, qu'importe ? / Au fond de l'Inconnu pour trouver du nouveau !’

[3] Heinrich Heine, ‘Einleitung von Heinrich Heine’, in Miguel de Cervantes, Der sinnreiche Junker Don Quixote von La Mancha, Brodhagsche Buchhandlung, Stuttgart, 1837 : ‘So pflegen immer große Poeten zu verfahren: sie begründen zugleich etwas Neues, indem sie das Alte zerstören; sie negieren nie, ohne etwas zu bejahen.’

– Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quijote de la Mancha, 1605.

Played with BertKnot.

Heinrich Heine, the last herald of German Romanticism and its gravedigger, was greatly inspired by Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quijote (1605). Just as the character fought against windmills to restore the grandeur of a picaresque chivalry, Heine fought against the established and conservative order. His idealistic passions led him to support the proponents of the French Revolution, but he also cultivated a deep spiritualism. Stirred by his inner paradoxes, Heine found in Don Quijote a way to reconcile his fragmented positions, embracing the biting irony of Cervantes. [1] In Die romantische Schule (1833), he compared the German and French branches of Romanticism in an attempt to identify their characteristics, achievements and shortcomings. In particular, Heine was highly suspicious of the propensity to recapture medieval spirituality, trapping Romanticism in adoration of the past to the detriment of contemporary experiences – found in the revolutionary cycles of the 19th century among others. In Baudelaire's words, what Heine wanted was 'to plunge into the depths of the Unknown and find something new' [2].

Striving for modernity: a proactive and more dynamic gameplay

Heine emphasised the extent to which Cervantes, by abolishing the picaresque tradition, opened a door for the modern novel and its new sensibilities: 'This is what the great poets will always do: they create something new by destroying the old: they never deny without affirming'. The characteristic strength of Don Quijote is that it genuinely celebrates the humanity and complexity of the hidalgo of La Mancha, rather than denying it altogether. Don Quijote's laughter is that of a man who sees his inability to fully live the role he has chosen for himself. The tragicomedy of the novel is born in the acute awareness of someone who knows that he is deceiving himself. Cervantes inaugurates a new tradition that does not completely reject the old, but draws lessons from it to create modernity: what matters is that something new is created. Resident Evil 4 (2023) also attempts to offer a fresh way of experiencing the classic title, which has proved to be one of the most fundamental in video game history and continues to be cited as a significant influence by many modern designers. Unlike Cervantes and all the writers he inspired, from Heine to Faulkner, this project does not manage to break free from the shackles imposed by the franchise, highlighting structural problems that are already apparent or are yet to come.

From the very first minutes, Resident Evil 4 (2023) establishes a much more serious tone and a more dynamic gameplay than its predecessor. These elements can be seen as an expression of the franchise's maturity and an attempt to modernise the title. These changes clearly affect the way the player interacts with the game. Combat sequences feel longer and more intense, becoming real tests of endurance that challenge the player's ability to manoeuvre in the arena and strategically engage the hordes of enemies. Encounters must take into account the new ability to shoot while moving and the greater versatility offered by the knife and its powerful parries. The player must move constantly, both to manage several fronts at once and to create space between Leon and the many enemies; as their grapple has a very high priority and the character's i-frames seem to have been shortened, it is essential to move wisely, as even knife parries cannot solve all situations.

This aggressive gameplay tends to work very well and keeps the player fully engaged while fighting. Some sequences can drag on – particularly towards the end of the game – but there is real enjoyment to be had from using heavy weapons, parrying attacks with the knife and delivering devastating high kicks. However, the title delivers its experience without fanfare when it tries to stick too closely to the source material. Bosses such as El Gigante come across as decent, while others are simply disappointing for want of ideas. Del Lago is vapid, full of archaisms that no longer elicit the same expressions of surprise as they did in 2005. The new gameplay would have encouraged more interaction with the environment; unfortunately, only the barrels are used and a certain visual fatigue can set in. Leon's kicks dominate the fights, and the rare German Supplex is only a tiny breath of fresh air. Because Resident Evil 4 (2023) stubbornly sticks to a very effective but rather simplistic combat formula, it suffers greatly in its later hours: KB0 has gone to great lengths to highlight the repetitive nature of the title, by analysing specific gameplay elements, and it seems superfluous to revisit them. Instead, it is the additions, such as the stealth sequence with the Garrador, that provide the necessary variety in a modernisation project.

Unambitious atmosphere and unflattering melodrama

To continue the Cervantes analogy, Resident Evil 4 (2023) may seem disappointing, taking no risks and offering no ambition for the future. What appear to be design updates to the original title are ultimately nothing more than bland gameplay elements from Resident Evil 5 (2008) and Resident Evil 6 (2012), whose remakes seem obvious given that the formula works commercially for Capcom. Unlike the attempt of Final Fantasy VII Remake (2020), which reinterpreted the original material in a durable way, Resident Evil 4 (2023) feels half-hearted, driven only by a desire to homogenise. This is not to say that the title is unpleasant, but it comes across as a technically accomplished but unexceptional product. The game presents itself as the ultimate version, which was not the case with the previous remakes, but it never manages to replace the original title, whose unique atmosphere cannot be imitated.

Perhaps because the environments are so detailed, silence no longer manages to conjure up its eerie strangeness; there is no room left for the player's imagination, and the first third of the game loses its evocative power. The view of the church in Resident Evil 4 (2023) is a clean gothic shot, but it is particularly plain. The golden light of the sun breaking through the clouds gives the place of worship a dignified and monumental nobility, rather than the tumultuous grime of the original. In 2005, the emphasis was on the cemetery rather than the building: this change of focus is representative of the game's approach, which is a little too forceful in directing the player's gaze. The atmosphere is sanitised by a multitude of details that do not convey anything. The decision to rely on notes to tell a story is an admission of failure by the title, which fails to put its great technical potential at the service of a subtle narration.

Resident Evil 4 (2023) is more serious and explores some of the characters more thoroughly. Krauser's backstory has been changed to make him a more coherent antagonist, but it is Luis Sera who benefits most from the remake's rewrite. Instead of being a superfluous companion, he is more directly involved in the story, as a series of dialogues and notes reveal the mask he wears to hide his embarrassment and guilt. Luis Sera is Don Quijote, whose adventures have lulled his childhood. Just as the hidalgo of La Mancha dreams of fantastic adventures beyond common understanding, Luis Sera succumbs to the sirens of unethical science. Both understand their mistake and try to make amends; they also share an honest laugh that reflects a partially assumed disenchantment. Resident Evil 4 (2023) shows genuine respect for the character, who inspires real sympathy in Leon and Ashley – perhaps a little too much – and whose code of conduct follows that of the picaresque hero. Krauser and Luis's rewrite could have taken the franchise in a new direction, one that looks at what defines humanity through the complex dilemmas it faces. The 'Resident Evil' title has historically pointed in that direction: a more intimate, character-driven horror.

The conservative roots of the series: from one sexualisation to another

Unfortunately, Resident Evil 4 (2023) does not seem to have realised this potential and justifies the rewriting of the characters for the sake of consistency. The only concern was to freshen up the game's narrative by cutting out the implausible passages. For example, Saddler only appears physically at the end of the game, which allowed for the removal of all his theatrical entrances, where he decided to stand in Leon's way but never kill him. Other changes have clearly been made to remove all the paedophile connotations of the original version. Ashley, still in her early twenties, goes from being a teenage girl to a young woman with a mesmerising face who openly plays on her charm. The majority of critics have seen this transformation in a positive light, never stopping to consider the retrograde representation it still constitutes. Is this because they are convinced of the importance of preserving the misogynistic frivolity of the original title? In any case, Ashley remains an objectified character, always driven by the desire to prove her – sexual – worth to Leon. Her teasing posture during the shooting mini-game is a poor choice, especially after the game's strong emphasis on the Illuminados' abhorrent tactility when dealing with her. The perspective of Resident Evil 4 (2023) is eminently perverse, extending far beyond a mere male gaze.

The franchise has always had a problem with its representation of women, relying on the figure of more or less strong women to fulfil male fantasies; what is particularly disappointing about Ashley's treatment is that it is yet another missed opportunity to provide depth to her character – just as Luis and Krauser were given. Instead of a proper treatment, she has simply been melted into a new sexualising archetype, while her function, for the plot and the audience, remains the same. This frustration is reinforced by Genevieve Buechner's convincing voice acting, which underlines the confidence she gradually gains during her adventure with Leon. But this confidence is immediately squandered by the game, which insists on her powerlessness. The section in which she is playable is pleasant and shows a heroine in the making, but she loses her agency extremely quickly, save for rare exceptions. Likewise, despite a veneer of respect, with Leon speaking Spanish once, the title stubbornly sticks to cultural clichés under the guise of humour, boding ill for the Resident Evil 5 remake.

For many people, Resident Evil 4 (2023) is a way to experience a legendary and beloved title after discovering the franchise with the recent remakes, Resident Evil 7 (2017) or Resident Evil Village (2021). They will not be confused, thanks to a grammar similar to the titles released in recent years. Unsurprisingly, many players have praised the game, saying that they understand why the original title is considered so valuable, even though they are only experiencing it through a standardised proxy. There is a certain irony in the fates of the Resident Evil 4 games, both of which, twenty years apart, confirm the franchise's transition into a new direction. In the case of the original, it was certainly a new modernity, whether one liked it or not, that caused the entire industry to adapt to a bold move. The remake is less about pushing the boundaries of the genre and more about obsequiously conforming to established formulas. Resident Evil 4 (2023) is a pleasure to play, because it borrows everything that is pleasing in the current grammar of game design, from combat dynamism to the importance of melee and parries. It all fits together elegantly, exploiting the strengths of the original level design to create a fresh experience. But it is a sterilised one, rejecting any idiosyncrasy, any stylistic boldness, any poetic imperfection. The strong sections generally remain strong, the weaker passages stay that way; the title never plunges into the unknown, never reveals anything new. The only daring thing about Resident Evil 4 (2023) is that it paves the way for the unnecessary remakes of the subsequent titles, with no guarantee that the sexism and racism that run through them will be amended. In the end, Don Quijote was only a misunderstood reference, never a model.

__________

[1] D. van Maelsaeke, ‘The Paradox of Humour: A Comparative Study of ‘Don Quixote’’, in Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, no. 28, 1967, pp. 24-42.

[2] Charles Baudelaire, ‘Le Voyage’, in Les Fleurs du mal, Poulet-Malassis et de Broise, Paris, 1861 : ‘Verse-nous ton poison pour qu'il nous réconforte ! / Nous voulons, tant ce feu nous brûle le cerveau, / Plonger au fond du gouffre, Enfer ou Ciel, qu'importe ? / Au fond de l'Inconnu pour trouver du nouveau !’

[3] Heinrich Heine, ‘Einleitung von Heinrich Heine’, in Miguel de Cervantes, Der sinnreiche Junker Don Quixote von La Mancha, Brodhagsche Buchhandlung, Stuttgart, 1837 : ‘So pflegen immer große Poeten zu verfahren: sie begründen zugleich etwas Neues, indem sie das Alte zerstören; sie negieren nie, ohne etwas zu bejahen.’

1984

‘If it be true that good wine needs no bush, ‘tis true that a good play needs no Epilogue. And [yet] good plays prove the better by the help of good Epilogues.’

– Rosalind, in William Shakespeare, As You Like It, Epilogue, 4-7.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (11th Apr. – 17th Apr., 2023).

Already accustomed to paraludic experimentation with PiMania (1982), a video game that doubled as a real-world treasure hunt and foreshadowed contemporary alternate-reality games, Croucher became convinced that the ZX81 was above all a creative platform for art with unlimited potential. In 1981, Welsh women protested against the storage of nuclear missiles at Greenham Common airbase, leading to a long escalation of the movement in the months and years that followed. The establishment of the Greenham Common camp was a key event in the English protest register of the 1980s. Mel Croucher, who was close to these circles and married to one of the protesters [1], imbued his artistic project Deus Ex Machina with the typical themes of the time: the game tells the story of a man's life under a dystopian and totalitarian regime through a sensory and artistic experience.

The title must be played together with a tape containing the title's soundtrack. From the start, the player must follow the audio instructions and synchronise the two components before immersing themselves in a psychedelic universe. The music takes full inspiration from Pink Floyd and Frank Zappa, mixing sung passages with theatrical narration, while the script takes Shakespearean passages and alters them to fit a dystopian aesthetic. Deus Ex Machina, for example, quotes Jaques' 'Seven Ages of Man' monologue in As You Like It (c. 1599). Misinterpretations have seen the famous monologue as a moralising critique of Orlando's behaviour in foolishly falling in love, rather than demonstrating the moral excellence of the Duke Senior. This overlooks the fact that As You Like It is a comedy, and that the passionate winds of love blow through the play: Orlando is not a character merely in love with romance, but a complex figure driven by authentic emotions. Most of the characters in the play are also imbued with genuine personalities.

On the contrary, Jaques is the only 'character', as he resembles the malcontents of Elizabeth I's reign, whose dissenting thoughts and potentially subversive actions are feared by the royal power. A great traveller, he is convinced that there are no universal values and that belief in anything – including love – is a sign of immaturity and folly. He shows little inclination to denigrate the foreigner, something Rosalind criticises him for – since xenophobia was a characteristic feature of English identity under the Tudors. Jaques is a counterbalance to the romanticism of the other characters in As You Like It. He is never sentimental or idealistic, preferring to wallow in cynical dilettantism. Yet Jaques, the eternal witness, is nowhere near as unpleasant as Shakespeare's other villains, far from the vile and contemptible Thersites (Troilus and Cressida, c. 1602) and Iago (Othello, c. 1603). One explanation could be that Shakespeare put himself into Jaques. Perhaps the playwright was bitter about his inability to conjure poetic magic outside the stage; Elizabethan society looked down on artists, and Jaques's tirades and his belief that the world is a stage should be seen as a self-effacing expression of artistic regret. [2]

Mel Croucher seems to have had the same creative drive, seeing potential in all forms of expression and believing that the world is indeed a playground for artistic experimentation. It is not surprising, then, that he also uses Prospero's speech in Act IV of The Tempest (c. 1610) before he decides to renounce magic. Just as the disappearance of magic in The Tempest allows Prospero to see the world more clearly, the end of the sensory experience in Deus Ex Machina invites the player to consider it in a broader context. This is not a simple video game, but a lively, vibrant and boundless artistic production, as the recommencement at the end of the title demonstrates. In Shakespeare's time, the baroque meraviglia took precedence over the supernatural miracle. In The Tempest, the idea of wonder is ever present, but it shifts from Prospero's magic to the possibility of social harmony and gentle human relationships. [3] Similarly, Croucher moves from the wonder the player can experience in Deus Ex Machina to a wonder for art in general, which is consubstantial to existence.

waverly_khitryy insisted on the transient nature of Deus Ex Machina, an analysis that I fully share. Croucher embraces the poetic and artistically curious voices of Jaques, Prospero and Shakespeare, blending them with his own experience and the cultural imagination of a protesting 1980s Britain. Orwellian accents sit alongside a veritable panorama of visual and auditive ideas: Croucher creates contrasts and uses mock interactivity to capture the player's attention. This ode to the ephemeral is above all an artistic statement whose contours are inevitably political. Because it makes no concessions, Deus Ex Machina is a unique avant-garde experience whose roughness is matched by an unusual creative exuberance.

__________

[1] Mel Croucher, Deus Ex Machina: The Best Game You Never Played in Your Life, Acorn Books, London, 2014, p. 45.

[2] William Shakespeare, Comédies, vol. II, ed. Jean-Michel Déprats, Gisèle Venet, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 2016, pp. 1534-1535.

[3] William Shakespeare, Comédies, vol. III, ed. Jean-Michel Déprats, Gisèle Venet, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 2016, pp. 1682-1683.

– Rosalind, in William Shakespeare, As You Like It, Epilogue, 4-7.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (11th Apr. – 17th Apr., 2023).

Already accustomed to paraludic experimentation with PiMania (1982), a video game that doubled as a real-world treasure hunt and foreshadowed contemporary alternate-reality games, Croucher became convinced that the ZX81 was above all a creative platform for art with unlimited potential. In 1981, Welsh women protested against the storage of nuclear missiles at Greenham Common airbase, leading to a long escalation of the movement in the months and years that followed. The establishment of the Greenham Common camp was a key event in the English protest register of the 1980s. Mel Croucher, who was close to these circles and married to one of the protesters [1], imbued his artistic project Deus Ex Machina with the typical themes of the time: the game tells the story of a man's life under a dystopian and totalitarian regime through a sensory and artistic experience.

The title must be played together with a tape containing the title's soundtrack. From the start, the player must follow the audio instructions and synchronise the two components before immersing themselves in a psychedelic universe. The music takes full inspiration from Pink Floyd and Frank Zappa, mixing sung passages with theatrical narration, while the script takes Shakespearean passages and alters them to fit a dystopian aesthetic. Deus Ex Machina, for example, quotes Jaques' 'Seven Ages of Man' monologue in As You Like It (c. 1599). Misinterpretations have seen the famous monologue as a moralising critique of Orlando's behaviour in foolishly falling in love, rather than demonstrating the moral excellence of the Duke Senior. This overlooks the fact that As You Like It is a comedy, and that the passionate winds of love blow through the play: Orlando is not a character merely in love with romance, but a complex figure driven by authentic emotions. Most of the characters in the play are also imbued with genuine personalities.

On the contrary, Jaques is the only 'character', as he resembles the malcontents of Elizabeth I's reign, whose dissenting thoughts and potentially subversive actions are feared by the royal power. A great traveller, he is convinced that there are no universal values and that belief in anything – including love – is a sign of immaturity and folly. He shows little inclination to denigrate the foreigner, something Rosalind criticises him for – since xenophobia was a characteristic feature of English identity under the Tudors. Jaques is a counterbalance to the romanticism of the other characters in As You Like It. He is never sentimental or idealistic, preferring to wallow in cynical dilettantism. Yet Jaques, the eternal witness, is nowhere near as unpleasant as Shakespeare's other villains, far from the vile and contemptible Thersites (Troilus and Cressida, c. 1602) and Iago (Othello, c. 1603). One explanation could be that Shakespeare put himself into Jaques. Perhaps the playwright was bitter about his inability to conjure poetic magic outside the stage; Elizabethan society looked down on artists, and Jaques's tirades and his belief that the world is a stage should be seen as a self-effacing expression of artistic regret. [2]

Mel Croucher seems to have had the same creative drive, seeing potential in all forms of expression and believing that the world is indeed a playground for artistic experimentation. It is not surprising, then, that he also uses Prospero's speech in Act IV of The Tempest (c. 1610) before he decides to renounce magic. Just as the disappearance of magic in The Tempest allows Prospero to see the world more clearly, the end of the sensory experience in Deus Ex Machina invites the player to consider it in a broader context. This is not a simple video game, but a lively, vibrant and boundless artistic production, as the recommencement at the end of the title demonstrates. In Shakespeare's time, the baroque meraviglia took precedence over the supernatural miracle. In The Tempest, the idea of wonder is ever present, but it shifts from Prospero's magic to the possibility of social harmony and gentle human relationships. [3] Similarly, Croucher moves from the wonder the player can experience in Deus Ex Machina to a wonder for art in general, which is consubstantial to existence.

waverly_khitryy insisted on the transient nature of Deus Ex Machina, an analysis that I fully share. Croucher embraces the poetic and artistically curious voices of Jaques, Prospero and Shakespeare, blending them with his own experience and the cultural imagination of a protesting 1980s Britain. Orwellian accents sit alongside a veritable panorama of visual and auditive ideas: Croucher creates contrasts and uses mock interactivity to capture the player's attention. This ode to the ephemeral is above all an artistic statement whose contours are inevitably political. Because it makes no concessions, Deus Ex Machina is a unique avant-garde experience whose roughness is matched by an unusual creative exuberance.

__________

[1] Mel Croucher, Deus Ex Machina: The Best Game You Never Played in Your Life, Acorn Books, London, 2014, p. 45.

[2] William Shakespeare, Comédies, vol. II, ed. Jean-Michel Déprats, Gisèle Venet, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 2016, pp. 1534-1535.

[3] William Shakespeare, Comédies, vol. III, ed. Jean-Michel Déprats, Gisèle Venet, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 2016, pp. 1682-1683.

1991

‘Someday, surely, you will lead the ship that is sinking in darkness into the light.’

By the turn of the 1990s, Squaresoft was working on several projects at once; in addition to Seiken Densetsu: The Emergence of Excalibur, the company planned to release two Final Fantasy games in 1991: Final Fantasy IV would be the last title for the Famicom, while Final Fantasy V would introduce the franchise to the Super Famicom. These numerous projects were cancelled while still in pre-production. Seiken Densetsu was nipped in the bud – the title was given to Gemma Knights, which became Seiken Densetsu: Final Fantasy Gaiden (1991), explaining the rather unexpected gameplay. As for Final Fantasy IV, little work had been done on it, and its cancellation was not an issue: Final Fantasy V took the title of Final Fantasy IV and combined all the efforts. After Final Fantasy III (1990), which was criticised by fans for its high difficulty and its two particularly treacherous final dungeons, Hironobu Sakaguchi's team decided to adopt a less old-fashioned approach, focusing on the new capabilities of the Super Famicom to embrace the franchise's cinematic ambitions. The gamble seemed to pay off, as the game was an exceptional critical success upon its release.

The opening cutscene: narrative ambitions around key characters

The player assumes the role of Cecil, commander of Baron's Red Wings, as he prepares to launch a raid on Mysidia to seize its Crystal. He is acting on the orders of the King of Baron, who is determined to collect the four Crystals divided between the different kingdoms: the violence of the raids weighs heavily on the shoulders of the Dark Knight, who begins to doubt his mission – a fact that does not go unnoticed by the Seneschal. Cecil is then stripped of his duties and sent to the village of Mist to kill a monster in the company of Kain, his best friend, much to Rosa's dismay. Although Final Fantasy IV retains the franchise's in medias res approach, it is also characterised by a more meticulous direction. The long introductory cutscene, interspersed with scripted battles, is accompanied by 'Red Wings', a fierce and percussive military march, as innocent people are slaughtered by Cecil and his soldiers. The triplets follow each other with force, giving the melody a sinister quality derived from Cecil's theme. The melodic motif is extremely dissonant, but finds small tonal resolutions here and there, foreshadowing the ethical doubts of the Dark Knight. This musical track should be contrasted with the discussion between Cecil and Rosa, which features the famous 'Theme of Love'.

This exemplary composition has become a classic representative of the series for its ability to evoke a plaintive and lovelorn nostalgia. This certainly explains why the second version, rearranged for the DS port, was included in the 2008 Kyoiku geijutsu sha recorder textbook for schoolchildren. The track follows the IVmaj⁷ – V⁷ – iii⁷ – vi progression favoured in Japanese compositions, yet begins with an ii⁷ chord, which not only allows for a cyclical progression, but also gives it a unique melancholic quality. This musical piece can be interpreted in many ways. With its very soft and soothing timbre, it is a perfect candidate to be Rosa's theme, heralding a long tradition for the series. The mournful motifs and lyrics of the two sung versions – Hikari no naka e (1994) and Tsuki no akari (2007) – position it rather within Kain's sorrows. Either way, this song immediately articulates the pain brewing in the love triangle of Baron's three characters, who are unable to express their deepest feelings. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the title's most poignant moments are always silent, with all communication taking place through sprite animation or music. Thus, from the very first minutes, Final Fantasy IV sets its stakes by emphasising the importance of the characters and their personalities, bringing it closer to Final Fantasy II (1988).

The melodramatic nature of the scenario

The idea of rebellion against an established order is present in Cecil's departure from Baron and his search for identity as he attempts to atone for the sins he committed with the Dark Knight's bloody sword. Final Fantasy IV depicts this introspection through a class change, but also through the cycle of tragedy that befalls the Overworld: the game repeatedly features ruins and a world destroyed by the ravages of war. This idea was also used in The Legend of Zelda (1986), with humanity forced to retreat into caves and tombs to survive monster attacks. However, Final Fantasy IV places the burden of responsibility on Cecil, the unsuspecting bearer of the fires of desolation. Baron, Mist, Damcyan and many other cities in the game lie in ruins throughout the adventure, an illustration of human cruelty – but also a sign of their resilience. Unlike Link in his first game, who single-handedly carries all of Hyrule's hopes, Cecil is written as a somewhat apprehensive and insecure character, forcing the rest of the cast to push him forward. Despite the pain he more or less directly inflicts on his companions, they are always there to help him make the right decisions and live up to his new code of ethics.

To compensate for the highly melodramatic nature of the script, Final Fantasy IV is more willing than previous titles to use good-natured humour, which helps to ease the tension. While Golbez, Rydia and Kain are constant reminders of Cecil's sins, characters such as Cid, Polom, Porom and Edge give the title some breathing room thanks to their sharper personalities, whose clichéd writing still manages to charm. The duo of Polom and Porom crystallise the hope for a better world, between childish arrogance and a strong sense of responsibility. Even if it does not achieve full narrative coherence, the world of Final Fantasy IV is teeming with life, both in its joys and its sorrows. The game is particularly effective at showing the characters' helplessness in the face of the reality of existence: this is often staged through scripted battles that function as pseudo-cutscenes in which interaction is possible, whether or not actions have real consequences. The sequence with Edge's parents is exemplary in this regard, managing to evoke the appropriate degree of dread and sadness and allowing the player to choose their actions: the ability to attack desperately or refuse to raise their weapons is a meaningful option.

Underused characters and a world lacking depth

Nevertheless, it is unfortunate that some narrative threads are resolved too hastily or lack subtlety. The first half of the game unfolds very quickly, leaving no time for dramatic tension to build. While Kain's troubled emotions are well portrayed through his silence and ever-downcast eyes, Rosa does not manage to conjure up the same complexity of character, something that writer Takashi Tokita actually laments. [1] She borrows all the traditional symbolism of Japanese beauty – the well-known triptych of moon, snow and flowers (setsu gekka) – in her design and way of expressing herself, but there are hints of agency thrown in here and there: at the beginning of the game, she admonishes Cecil with the famous 'Cecil is not a coward, not the Cecil I love', which puts her in the role of judge and upholder of an ethical code. She does come across as a little forceful – presumably due to the difficulty of communicating subtle emotions with the technical limitations of the time – when she asks Rydia to use Fire. Throughout the game, Rosa embodies the gentleness of the moon, providing a counterpoint to the Red Moon that hangs mysteriously and ominously in the night sky – a sort of representation of Cecil's spilt blood. Final Fantasy IV further develops the opposition between worlds that seem irreconcilable, but must learn to cooperate in order to find balance. The Dark Crystals return from Final Fantasy III to contrast with the Light Crystals, but there are also parallels between the races of the Blue Planet and the Lunarians; the inhabitants of the Overworld and Underworld; the humanoid races and the mythical Eidolons.

Unfortunately, all of these themes, although apparent during the adventure, are generally not explored. Rosa too often remains a damsel in distress, acting as a catalyst for the development of Cecil and Kain, while the Lunarians' background is left aside, except for a few mentions at the end of the game. Admittedly, some scenes remain compelling, such as Cecil's return to Mysidia and his interactions with the inhabitants, but they are in the minority. The game focuses mainly on the relationships between the main characters and less on the world around them, with the exception of the ruins' aesthetics. The emphasis on pseudo-erotic scenes with all the dancers, in the spirit of Dragon Quest, is also a puzzling and unwelcome touch. Final Fantasy IV does not manage to completely imbue its universe with a coherent poetic aura, often leaving it to the soundtrack to fill in the gaps in the script. Edward's sequences, in particular, are carried by the superb 'Castle Damcyan', whose pathetic and tired tone serves to underline the prince's difficult grief. Similarly, the sense of adventure is mostly underlined by the sweeping arpeggios and modal mixtures of the 'Overworld Theme', which borrows heavily from the 'Prelude'.

The ATB system and the new dynamics of combat

The narrative ambitions are largely based on a new gameplay system that alters the structure of the story. In a sort of evolution of the Final Fantasy III concept, up to five characters can form a team, and Final Fantasy IV does not hesitate to add or remove team members in order to vary gameplay styles and prepare its narrative twists. While this feature is functional, it can also be a bit contrived, as the player can lose equipment when a character leaves the team. Nevertheless, the game has good mechanical variety and the idea of having fixed archetypes, as opposed to the job system, works well. The ATB system provides the necessary amount of flexibility and tension in combat without ever being too punishing. The player is encouraged to truly master the tools of all characters, rather than spamming the same option just to move on to the next character. This philosophy can put the player in a corner, as Final Fantasy IV has a large number of enemies – even common ones – that can counter attacks under certain conditions: using Black Magic on a particular enemy can be fatal, as it would trigger a powerful counter-attack that takes precedence over the ATB initiative order.

The player has to memorise the actions of most enemies and pay attention to the effects they can produce. The approach is very effective on bosses, where the task is to identify the lethal gimmick as quickly as possible, but poses more problems on standard enemies. Every fight can be an uphill battle, quickly draining the player's mental resources. Some of the dungeons feel particularly sluggish and make for cruel challenges, just to get to the boss. The last dungeon is theoretically less extensive than its Final Fantasy III counterpart, but some of the standard enemies, formerly bosses, can easily erode the player's patience. Although Save Points are available and make progression more convenient, it is a challenge that may put off less dedicated players, for whom grinding may seem a more pleasant option.

Questionable ergonomics and asymmetric progression

While Final Fantasy IV has many more tools to build interesting battles, the game is undermined by its poor inventory system. The title's emphasis on elemental resistances, buffs and debuffs encourages the player to stock up on as many consumables as possible in order to be flexible in different situations. However, the inventory is limited to 48 slots. It is therefore impossible to have a transversal arsenal, especially as some slots have to be saved for the equipment of characters who leave and return to the party. Should one save a caster's robe for Rydia, who will be returning to the party, or would one rather have an extra slot? Questions like these break up the pace of progression: until the very end of the game, it is impossible to call the Fat Chocobo outside of a few fixed locations to transfer items to the reserve. Final Fantasy IV thus reinforces the stigma of not using consumables, which are often vulgarly abandoned. The peculiarity of Lodestone Cavern, forcing the use of certain types of equipment, makes this even worse.

Similarly, the constant switching of characters brings up the issue of experience grinding: even though Final Fantasy IV is relatively forgiving until the final hours, there are sections that are more difficult as a result of a more fragile team composition dominated by mages. These moments are conducive to grinding, but they only apply to the characters currently on the team. Although not dramatic, a certain asymmetry can arise and, in the GBA and later versions, certain characters are relegated to the bench, as it is possible to modify the party for the final section of the game. Yang and Rydia seem to be the most flexible powerhouses, while Edward, Kain and Cid struggle to dramatically increase their damage output compared to other characters.

Also worth noting is the presence of side content, which is unlocked after the Tower of Babil. Players can explore the world and undertake a range of quests and battles to increase the party's power. These sequences are a welcome respite from the hectic pace of the story, but they remain relatively minor, though important for their rewards. The optional dungeons in the GBA version are generally mediocre: the Cave of Trials is a series of forgettable floors that allow the player to face five bosses with the characters available after the Tower of Babil. The Lunar Ruins introduces a long dungeon with randomised floors, enabling access to the Trials of the characters present in the party during the final boss fight. These scenarios vary in quality – Kain is certainly the most interesting and Edge the most frustrating – and provide the most powerful equipment in the game. The problem comes mainly from the floors in between, which are hardly appealing to explore, usually lacklustre puzzles or the rooms from previous dungeons, especially as it takes several runs to complete all the challenges. The highlight is undoubtedly the battle against the superboss, which is far easier to digest than the floor exploration. Special mention should be made of the Pink Tail and Rydia's summons, which involve a gruelling grinding experience representative of the worst JRPGs have to offer, due to their abysmal drop rate.

The transition to the Super Famicom allowed Final Fantasy IV to develop greater ambitions and acquire the technical tools necessary to better present its story and combat. This first attempt is productive and full of brilliant compositional strokes, but the title lacks coherence and fails to establish an effective rhythm over the course of its adventure. The multiplication of environments, even though it is a characteristic of the genre, forces certain narrative concessions and relegates certain characters to the background. Nevertheless, Final Fantasy IV in its own way embodies the peculiar magic of old-school Final Fantasy. Its antagonists are memorable, and it is commendable that they were only minimally altered for their inclusion in Final Fantasy XIV: Endwalker (2021). Final Fantasy IV may lack subtle poetry, but ten years after I first discovered it, the title retains its charm, despite the mediocre and plain graphical assets of the PSP version.

__________

[1] ‘FINAL FANTASY IV 30th Anniversary Special Interview!’, in Final Fantasy Portal Site, 16th June 2021, consulted on 11th April 2023.

By the turn of the 1990s, Squaresoft was working on several projects at once; in addition to Seiken Densetsu: The Emergence of Excalibur, the company planned to release two Final Fantasy games in 1991: Final Fantasy IV would be the last title for the Famicom, while Final Fantasy V would introduce the franchise to the Super Famicom. These numerous projects were cancelled while still in pre-production. Seiken Densetsu was nipped in the bud – the title was given to Gemma Knights, which became Seiken Densetsu: Final Fantasy Gaiden (1991), explaining the rather unexpected gameplay. As for Final Fantasy IV, little work had been done on it, and its cancellation was not an issue: Final Fantasy V took the title of Final Fantasy IV and combined all the efforts. After Final Fantasy III (1990), which was criticised by fans for its high difficulty and its two particularly treacherous final dungeons, Hironobu Sakaguchi's team decided to adopt a less old-fashioned approach, focusing on the new capabilities of the Super Famicom to embrace the franchise's cinematic ambitions. The gamble seemed to pay off, as the game was an exceptional critical success upon its release.

The opening cutscene: narrative ambitions around key characters

The player assumes the role of Cecil, commander of Baron's Red Wings, as he prepares to launch a raid on Mysidia to seize its Crystal. He is acting on the orders of the King of Baron, who is determined to collect the four Crystals divided between the different kingdoms: the violence of the raids weighs heavily on the shoulders of the Dark Knight, who begins to doubt his mission – a fact that does not go unnoticed by the Seneschal. Cecil is then stripped of his duties and sent to the village of Mist to kill a monster in the company of Kain, his best friend, much to Rosa's dismay. Although Final Fantasy IV retains the franchise's in medias res approach, it is also characterised by a more meticulous direction. The long introductory cutscene, interspersed with scripted battles, is accompanied by 'Red Wings', a fierce and percussive military march, as innocent people are slaughtered by Cecil and his soldiers. The triplets follow each other with force, giving the melody a sinister quality derived from Cecil's theme. The melodic motif is extremely dissonant, but finds small tonal resolutions here and there, foreshadowing the ethical doubts of the Dark Knight. This musical track should be contrasted with the discussion between Cecil and Rosa, which features the famous 'Theme of Love'.

This exemplary composition has become a classic representative of the series for its ability to evoke a plaintive and lovelorn nostalgia. This certainly explains why the second version, rearranged for the DS port, was included in the 2008 Kyoiku geijutsu sha recorder textbook for schoolchildren. The track follows the IVmaj⁷ – V⁷ – iii⁷ – vi progression favoured in Japanese compositions, yet begins with an ii⁷ chord, which not only allows for a cyclical progression, but also gives it a unique melancholic quality. This musical piece can be interpreted in many ways. With its very soft and soothing timbre, it is a perfect candidate to be Rosa's theme, heralding a long tradition for the series. The mournful motifs and lyrics of the two sung versions – Hikari no naka e (1994) and Tsuki no akari (2007) – position it rather within Kain's sorrows. Either way, this song immediately articulates the pain brewing in the love triangle of Baron's three characters, who are unable to express their deepest feelings. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the title's most poignant moments are always silent, with all communication taking place through sprite animation or music. Thus, from the very first minutes, Final Fantasy IV sets its stakes by emphasising the importance of the characters and their personalities, bringing it closer to Final Fantasy II (1988).

The melodramatic nature of the scenario

The idea of rebellion against an established order is present in Cecil's departure from Baron and his search for identity as he attempts to atone for the sins he committed with the Dark Knight's bloody sword. Final Fantasy IV depicts this introspection through a class change, but also through the cycle of tragedy that befalls the Overworld: the game repeatedly features ruins and a world destroyed by the ravages of war. This idea was also used in The Legend of Zelda (1986), with humanity forced to retreat into caves and tombs to survive monster attacks. However, Final Fantasy IV places the burden of responsibility on Cecil, the unsuspecting bearer of the fires of desolation. Baron, Mist, Damcyan and many other cities in the game lie in ruins throughout the adventure, an illustration of human cruelty – but also a sign of their resilience. Unlike Link in his first game, who single-handedly carries all of Hyrule's hopes, Cecil is written as a somewhat apprehensive and insecure character, forcing the rest of the cast to push him forward. Despite the pain he more or less directly inflicts on his companions, they are always there to help him make the right decisions and live up to his new code of ethics.

To compensate for the highly melodramatic nature of the script, Final Fantasy IV is more willing than previous titles to use good-natured humour, which helps to ease the tension. While Golbez, Rydia and Kain are constant reminders of Cecil's sins, characters such as Cid, Polom, Porom and Edge give the title some breathing room thanks to their sharper personalities, whose clichéd writing still manages to charm. The duo of Polom and Porom crystallise the hope for a better world, between childish arrogance and a strong sense of responsibility. Even if it does not achieve full narrative coherence, the world of Final Fantasy IV is teeming with life, both in its joys and its sorrows. The game is particularly effective at showing the characters' helplessness in the face of the reality of existence: this is often staged through scripted battles that function as pseudo-cutscenes in which interaction is possible, whether or not actions have real consequences. The sequence with Edge's parents is exemplary in this regard, managing to evoke the appropriate degree of dread and sadness and allowing the player to choose their actions: the ability to attack desperately or refuse to raise their weapons is a meaningful option.

Underused characters and a world lacking depth

Nevertheless, it is unfortunate that some narrative threads are resolved too hastily or lack subtlety. The first half of the game unfolds very quickly, leaving no time for dramatic tension to build. While Kain's troubled emotions are well portrayed through his silence and ever-downcast eyes, Rosa does not manage to conjure up the same complexity of character, something that writer Takashi Tokita actually laments. [1] She borrows all the traditional symbolism of Japanese beauty – the well-known triptych of moon, snow and flowers (setsu gekka) – in her design and way of expressing herself, but there are hints of agency thrown in here and there: at the beginning of the game, she admonishes Cecil with the famous 'Cecil is not a coward, not the Cecil I love', which puts her in the role of judge and upholder of an ethical code. She does come across as a little forceful – presumably due to the difficulty of communicating subtle emotions with the technical limitations of the time – when she asks Rydia to use Fire. Throughout the game, Rosa embodies the gentleness of the moon, providing a counterpoint to the Red Moon that hangs mysteriously and ominously in the night sky – a sort of representation of Cecil's spilt blood. Final Fantasy IV further develops the opposition between worlds that seem irreconcilable, but must learn to cooperate in order to find balance. The Dark Crystals return from Final Fantasy III to contrast with the Light Crystals, but there are also parallels between the races of the Blue Planet and the Lunarians; the inhabitants of the Overworld and Underworld; the humanoid races and the mythical Eidolons.

Unfortunately, all of these themes, although apparent during the adventure, are generally not explored. Rosa too often remains a damsel in distress, acting as a catalyst for the development of Cecil and Kain, while the Lunarians' background is left aside, except for a few mentions at the end of the game. Admittedly, some scenes remain compelling, such as Cecil's return to Mysidia and his interactions with the inhabitants, but they are in the minority. The game focuses mainly on the relationships between the main characters and less on the world around them, with the exception of the ruins' aesthetics. The emphasis on pseudo-erotic scenes with all the dancers, in the spirit of Dragon Quest, is also a puzzling and unwelcome touch. Final Fantasy IV does not manage to completely imbue its universe with a coherent poetic aura, often leaving it to the soundtrack to fill in the gaps in the script. Edward's sequences, in particular, are carried by the superb 'Castle Damcyan', whose pathetic and tired tone serves to underline the prince's difficult grief. Similarly, the sense of adventure is mostly underlined by the sweeping arpeggios and modal mixtures of the 'Overworld Theme', which borrows heavily from the 'Prelude'.

The ATB system and the new dynamics of combat

The narrative ambitions are largely based on a new gameplay system that alters the structure of the story. In a sort of evolution of the Final Fantasy III concept, up to five characters can form a team, and Final Fantasy IV does not hesitate to add or remove team members in order to vary gameplay styles and prepare its narrative twists. While this feature is functional, it can also be a bit contrived, as the player can lose equipment when a character leaves the team. Nevertheless, the game has good mechanical variety and the idea of having fixed archetypes, as opposed to the job system, works well. The ATB system provides the necessary amount of flexibility and tension in combat without ever being too punishing. The player is encouraged to truly master the tools of all characters, rather than spamming the same option just to move on to the next character. This philosophy can put the player in a corner, as Final Fantasy IV has a large number of enemies – even common ones – that can counter attacks under certain conditions: using Black Magic on a particular enemy can be fatal, as it would trigger a powerful counter-attack that takes precedence over the ATB initiative order.

The player has to memorise the actions of most enemies and pay attention to the effects they can produce. The approach is very effective on bosses, where the task is to identify the lethal gimmick as quickly as possible, but poses more problems on standard enemies. Every fight can be an uphill battle, quickly draining the player's mental resources. Some of the dungeons feel particularly sluggish and make for cruel challenges, just to get to the boss. The last dungeon is theoretically less extensive than its Final Fantasy III counterpart, but some of the standard enemies, formerly bosses, can easily erode the player's patience. Although Save Points are available and make progression more convenient, it is a challenge that may put off less dedicated players, for whom grinding may seem a more pleasant option.

Questionable ergonomics and asymmetric progression

While Final Fantasy IV has many more tools to build interesting battles, the game is undermined by its poor inventory system. The title's emphasis on elemental resistances, buffs and debuffs encourages the player to stock up on as many consumables as possible in order to be flexible in different situations. However, the inventory is limited to 48 slots. It is therefore impossible to have a transversal arsenal, especially as some slots have to be saved for the equipment of characters who leave and return to the party. Should one save a caster's robe for Rydia, who will be returning to the party, or would one rather have an extra slot? Questions like these break up the pace of progression: until the very end of the game, it is impossible to call the Fat Chocobo outside of a few fixed locations to transfer items to the reserve. Final Fantasy IV thus reinforces the stigma of not using consumables, which are often vulgarly abandoned. The peculiarity of Lodestone Cavern, forcing the use of certain types of equipment, makes this even worse.

Similarly, the constant switching of characters brings up the issue of experience grinding: even though Final Fantasy IV is relatively forgiving until the final hours, there are sections that are more difficult as a result of a more fragile team composition dominated by mages. These moments are conducive to grinding, but they only apply to the characters currently on the team. Although not dramatic, a certain asymmetry can arise and, in the GBA and later versions, certain characters are relegated to the bench, as it is possible to modify the party for the final section of the game. Yang and Rydia seem to be the most flexible powerhouses, while Edward, Kain and Cid struggle to dramatically increase their damage output compared to other characters.

Also worth noting is the presence of side content, which is unlocked after the Tower of Babil. Players can explore the world and undertake a range of quests and battles to increase the party's power. These sequences are a welcome respite from the hectic pace of the story, but they remain relatively minor, though important for their rewards. The optional dungeons in the GBA version are generally mediocre: the Cave of Trials is a series of forgettable floors that allow the player to face five bosses with the characters available after the Tower of Babil. The Lunar Ruins introduces a long dungeon with randomised floors, enabling access to the Trials of the characters present in the party during the final boss fight. These scenarios vary in quality – Kain is certainly the most interesting and Edge the most frustrating – and provide the most powerful equipment in the game. The problem comes mainly from the floors in between, which are hardly appealing to explore, usually lacklustre puzzles or the rooms from previous dungeons, especially as it takes several runs to complete all the challenges. The highlight is undoubtedly the battle against the superboss, which is far easier to digest than the floor exploration. Special mention should be made of the Pink Tail and Rydia's summons, which involve a gruelling grinding experience representative of the worst JRPGs have to offer, due to their abysmal drop rate.

The transition to the Super Famicom allowed Final Fantasy IV to develop greater ambitions and acquire the technical tools necessary to better present its story and combat. This first attempt is productive and full of brilliant compositional strokes, but the title lacks coherence and fails to establish an effective rhythm over the course of its adventure. The multiplication of environments, even though it is a characteristic of the genre, forces certain narrative concessions and relegates certain characters to the background. Nevertheless, Final Fantasy IV in its own way embodies the peculiar magic of old-school Final Fantasy. Its antagonists are memorable, and it is commendable that they were only minimally altered for their inclusion in Final Fantasy XIV: Endwalker (2021). Final Fantasy IV may lack subtle poetry, but ten years after I first discovered it, the title retains its charm, despite the mediocre and plain graphical assets of the PSP version.

__________

[1] ‘FINAL FANTASY IV 30th Anniversary Special Interview!’, in Final Fantasy Portal Site, 16th June 2021, consulted on 11th April 2023.

1999

「灼熱のファイヤーダンス、星空まで全て手に入れた。」

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (Apr. 4 – Apr. 10, 2023).

The late 1990s saw both the rise and almost immediate collapse of the Compile financial empire. Their Puyoman manjū with the Puyo Puyo image made a lasting impression and, thanks to their popularity, served to reassure investors that the company's portfolio was diversified enough to avoid bankruptcy with more profitable activities than game sales. The very competitive nature of the Japanese market, which remains insular and attracts little foreign investment, forces such strategies, especially in the case of Compile. It was a successful venture, but the aggressive expansion beyond video games drained the company's financial resources. The failure of POWER ACTY (1998), a kind of productivity application for businesses, due to questionable marketing, finally shattered Compile's hopes and forced it to declare bankruptcy, along with other failed projects. It was in this context that Puyo Puyo DA! was released, after SEGA had already acquired the rights to the franchise's characters.

Based on the concept introduced in Broadway Legend Ellena (1994), Puyo Puyo DA! is a surprisingly brief experience. The player can compete against the computer or another player in an asymmetrical rhythm duel; instead of playing at the same time, the opponents alternate between active and passive phases, repeating the same musical phrase. The title loosely follows the concept of Puyo Puyo with a Chain mechanic, which allows Garbage Puyo to be sent at the opponent to lower their life bar, but which struggles to be anything more than the reskin of a combo mechanic. Unlike Broadway Legend Ellena, which tests the player's memorization skills, Puyo Puyo DA! focuses on fast sightreading and staying in rhythm. This is not helped by the choice of controls, which were better suited to a less intensive experience like Broadway Legend Ellena. On the hard difficulty, having to chain notes together in very quick succession with the thumb alone is not very pleasant.

The fundamental problem, however, is that the required inputs have nothing to do with the music. If the player is just beating the rhythm of the song, this is generally harmless, but the situation quickly becomes chaotic when the title asks the player to pulse on eighth notes, as the music does not follow this rhythm at all. In the duel between Rulue and Satan, some phrases shift slightly from the last notes, distorting the natural rhythm heard for no good reason. This lack of overall vision tends to paint Puyo Puyo DA! as an offhand translation of the Broadway Legend Ellena concept to a more traditional rhythm game. The small number of songs – only a dozen or so – is also unfortunate, even if some of them, drawn from the franchise's legacy, evoke a strong city-pop nostalgia: Shakunetsu no Fire Dance, used for the TV commercials of Puyo Puyo 2 (1994), is a particularly catchy tune. It is a shame that it, like the rest of the music, is so poorly exploited.

Puyo Puyo DA! is Compile's final original attempt to exploit their franchise. Unfortunately, the title struggles to conjure up the charm of the series, and Masamitsu Nītani's message in the game's manual rings oddly hollow, as does his optimism. Admittedly, Puyo Puyo Box (2000), Compile's last game, is a well-made compilation, but Puyo Puyo DA! sends Compile out without fanfare. The game over theme, Heartbreak, is sung by Nītani himself; somewhat ironically, his plaintive tone is probably a very fitting expression of the end of the company's prosperous years.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (Apr. 4 – Apr. 10, 2023).