PasokonDeacon

1980

tim rogers voice I Was a Sierra On-Line Poser smashes keyboard on stage and plays foosball with the keycaps

Like many others who love media history but struggle to get into or make time for certain parts of it, the formative parser-driven adventure games like Wander, Colossal Cave Adventure, and Sierra On-Line's classics like Mystery House have eluded me. But I'm also guilty of just not going for them like a hunter chases flock, or a prospector dives for gold. To have this apathy, despite knowing pretty much all these games are easily playable on Internet Archive, ate at me until recently. Something's clicked—probably just the satisfaction of completing Myst last month after years of never clearing the first island. But that's enough to get me committed to trying these ramshackle first attempts at conjuring immersive worlds on the earliest home computer platforms.

Mission Asteroid had a simple, er, mission: introduce any and all possible Apple II users to the graphic text adventure. Roberta Williams knew this didn't have to be as intricate as her Agatha Christie-esque first game, nor as fanciful as The Wizard and the Princess. A solid, pulp-y "save the Earth!" story could get you used to the studio's text parser, thinking up valid verb combinations, and managing your time and patience wisely. No matter how much this game continues to age like an indescribable beverage, it still fulfills those criteria. That's a nice way of saying this 1980 release had much less bullshit puzzling and navigation than its peers.

What the Williams duo would have called "simple" or "entry-level" then is considered hard to parse today dodges tomatoes after that pun. You've got the usual N-S-E-W compass commands, sure, but also instances of having to enter door rather than just go north through it. The two-word restriction on your interactions becomes painfully clear when trying to do something as straightforward as insert a floppy disk into the mission HQ Apple II. You type take disk, carriage return, and then insert disk (repeat), only for the game to ask where you're inserting this thing. There's no death branch here if you specify the wrong target or anything, just needless busywork compounded by the parser system.

Yet, for all the grief these simplistic parsers give me, there's still the fun of tinkering with what hidden-in-plain-sight options you can type in. All the gizmos in your space rocket can either doom you or take you on a disorienting ride through Earth orbit, controlled only by your type-in commands. Wandering the asteroid itself becomes a tense adventure as you likely know from harsh experience that the air supply's time-limited. Once the game lifts its tutorializing gaze from you, Mission Asteroid feels like an organic interplay between you, the reader asking questions, and the ghost of a game master hiding in the machine. It's easier now to see how Roberta, Ken, and others who'd soon join On-Line Systems could champion this genre framework.

Obviously there's not much to look at in this now, with its rudimentary VersaWriter drawings and lack of sound design. At the end of the day, most of the puzzles are either too simple to satisfy or convoluted enough to irritate me a bit too much. But I can gladly say that Mission Asteroid's an easier way to start playing turn-of-the-'80s graphic text stories than I've been told. It gets you into the necessary frame of mind with relatively little condescending scenarios or design language. The truly brutal riddles and cat's cradles of contemporary text adventures are reduced in scope, tightening up the pace. One gets to have a just-filling-enough time with the genre here before it overstays its welcome, either by avoiding a glut of bad ends or treating the player's time with more respect. I sense and can only speculate that Roberta's need to finish this romp for the holidays, capitalizing on Mystery House's success, left less room for potentially harmful experiments or indulgence.

So it's the definition of mid, yet I can't hold that against this game in retrospect. There's much worse one could try from that era, ranging from Scott Adams' pioneering all-text enigmas to their slapdash imitators on TRS-80 or Commodore PET (take your pick of PC cheaper than the Apple ][+). Given how Mission Asteroid itself avoids some of the amateur mistakes in Mystery House I hear about, I'm not content slapping this with a 2-star and calling it there. Whether or not it's a labor of love on par with Sierra On-Line's adventures soon to come, this little ditty of a day's work blowing up an asteroid punches above its weight class where it counts. Some higher being oughta know we got more than we asked for when Michael Bay's people adapted the premise almost two decades later. Keep it simple, Sierra!

Like many others who love media history but struggle to get into or make time for certain parts of it, the formative parser-driven adventure games like Wander, Colossal Cave Adventure, and Sierra On-Line's classics like Mystery House have eluded me. But I'm also guilty of just not going for them like a hunter chases flock, or a prospector dives for gold. To have this apathy, despite knowing pretty much all these games are easily playable on Internet Archive, ate at me until recently. Something's clicked—probably just the satisfaction of completing Myst last month after years of never clearing the first island. But that's enough to get me committed to trying these ramshackle first attempts at conjuring immersive worlds on the earliest home computer platforms.

Mission Asteroid had a simple, er, mission: introduce any and all possible Apple II users to the graphic text adventure. Roberta Williams knew this didn't have to be as intricate as her Agatha Christie-esque first game, nor as fanciful as The Wizard and the Princess. A solid, pulp-y "save the Earth!" story could get you used to the studio's text parser, thinking up valid verb combinations, and managing your time and patience wisely. No matter how much this game continues to age like an indescribable beverage, it still fulfills those criteria. That's a nice way of saying this 1980 release had much less bullshit puzzling and navigation than its peers.

What the Williams duo would have called "simple" or "entry-level" then is considered hard to parse today dodges tomatoes after that pun. You've got the usual N-S-E-W compass commands, sure, but also instances of having to enter door rather than just go north through it. The two-word restriction on your interactions becomes painfully clear when trying to do something as straightforward as insert a floppy disk into the mission HQ Apple II. You type take disk, carriage return, and then insert disk (repeat), only for the game to ask where you're inserting this thing. There's no death branch here if you specify the wrong target or anything, just needless busywork compounded by the parser system.

Yet, for all the grief these simplistic parsers give me, there's still the fun of tinkering with what hidden-in-plain-sight options you can type in. All the gizmos in your space rocket can either doom you or take you on a disorienting ride through Earth orbit, controlled only by your type-in commands. Wandering the asteroid itself becomes a tense adventure as you likely know from harsh experience that the air supply's time-limited. Once the game lifts its tutorializing gaze from you, Mission Asteroid feels like an organic interplay between you, the reader asking questions, and the ghost of a game master hiding in the machine. It's easier now to see how Roberta, Ken, and others who'd soon join On-Line Systems could champion this genre framework.

Obviously there's not much to look at in this now, with its rudimentary VersaWriter drawings and lack of sound design. At the end of the day, most of the puzzles are either too simple to satisfy or convoluted enough to irritate me a bit too much. But I can gladly say that Mission Asteroid's an easier way to start playing turn-of-the-'80s graphic text stories than I've been told. It gets you into the necessary frame of mind with relatively little condescending scenarios or design language. The truly brutal riddles and cat's cradles of contemporary text adventures are reduced in scope, tightening up the pace. One gets to have a just-filling-enough time with the genre here before it overstays its welcome, either by avoiding a glut of bad ends or treating the player's time with more respect. I sense and can only speculate that Roberta's need to finish this romp for the holidays, capitalizing on Mystery House's success, left less room for potentially harmful experiments or indulgence.

So it's the definition of mid, yet I can't hold that against this game in retrospect. There's much worse one could try from that era, ranging from Scott Adams' pioneering all-text enigmas to their slapdash imitators on TRS-80 or Commodore PET (take your pick of PC cheaper than the Apple ][+). Given how Mission Asteroid itself avoids some of the amateur mistakes in Mystery House I hear about, I'm not content slapping this with a 2-star and calling it there. Whether or not it's a labor of love on par with Sierra On-Line's adventures soon to come, this little ditty of a day's work blowing up an asteroid punches above its weight class where it counts. Some higher being oughta know we got more than we asked for when Michael Bay's people adapted the premise almost two decades later. Keep it simple, Sierra!

2003

Credit where it's due: at least the Game Boy Camera and SEGA's DreamEye got treated with enough dignity to never suffer a minigame collection this lame.

More credit goes to London Studio for injecting some much-needed, if dated amount of personality where it counts. I'll always fondly remember unpacking this honestly not terrible webcam (Logitech wasn't much better in '03), then loading into the cheeky, very post-Psygnosis tutorial movie explaining how to use the peripheral. Watching what might as well be the queen mother and her clones dancing to stock library disco as the Stanley Parable narrator goodbye-s you is still surreal. I wish the game itself had as much family-friendly anarchy. Part of me wants to argue the inconsistent art direction between minigames brings this closer to WarioWare or a modern game jam, but it's just not there.

With 12 minigames of varying quality on offer, Sony's making a go at matching its competitors in silly gimmickry. A good chunk of the experience revolves around variations on whack-a-mole, or something like those Moorhuhn (Crazy Chicken) shovelware titles you see every now and then. This whole idea of pairing a novel, limited but intriguing add-on console toy with what amounts to a prototype Carnival Games worked at the time. The folks & I had a solid time looking stupid in front of the TV, though my sister stuck mostly to our metal DDR pad since those games had far more substance. Little did we know this would have us wibblin' and wobblin' in the living room some years later—that was Wii Sports, though, which remains far more replayable in 2023.

EyeToy Play is fun enough for what it is, a serviceable pack-in game which took the safe route with proving that this idea could even work. Nintendo's aforementioned handheld lens toy has somehow managed to age better by dint of offering a uniquely lo-fi experience, though. Going from harsh but exotic monochrome games and photo printing to the blurry, often out-of-focus mess EyeToy provides seems a bit underwhelming nowadays. What I really lament, though, is the C-rate Y2K aesthetic dominating this collection. (Half of the game looks like it's recycling unused Psybadek concepts, mashing them up with Gorillaz and other post-Y2K intercontinental mascot designs.) It just reminds me too much of when these developers, a mix of ex-Psygnosis fellas and The Getaway's team, had more creative projects to work on.

Again, this isn't a strictly bad game. Most minigames work properly with the EyeToy in most room settings, and it's a bit amusing to wave your arms around, a kind of bastardized ParaPara Paradise or Samba de Amigo for the new era. Just temper your expectations if you collect one of these square, googly things and stick this in your PS2. I'd personally rather play SEGA Superstars if only for the IP variety and actual Samba de Amigo experience. However, the lack of ambition and increasingly quaint presentation behind this pack-in was kind of the point. If it was too good a free disc to keep playing, would you have bought all those other EyeToy games coming later? Consider how Nintendo fell into that trap later, with Wii Sports & Play offering enough for most owners to just skip out on following minigame collections (or settle for the bargain bin equivalents).

See, this is exactly what Thursday does to an oldhead like me. I get vaguely nostalgic thoughts about what passed muster for party night amusement at the end of elementary school, and then I think harder about what this was actually like. Youngsters have it so much easier in these social media dog days. EyeToy: Play was the offline TikTok dance simulator of its day, cheaper than a ParaPara cab every weekend but not much more advanced than some plastic maracas. Games like this fall through the cracks of half-remembered cringe and convenient historic amnesia—some would say for the better. I just feel sorry for all the UK devs Sony chopped into teams like London Studio, who then had to take any mid project they could get by their corporate sponsor. tl;dr Where the hell's the Wipeout minigame in this set?!

More credit goes to London Studio for injecting some much-needed, if dated amount of personality where it counts. I'll always fondly remember unpacking this honestly not terrible webcam (Logitech wasn't much better in '03), then loading into the cheeky, very post-Psygnosis tutorial movie explaining how to use the peripheral. Watching what might as well be the queen mother and her clones dancing to stock library disco as the Stanley Parable narrator goodbye-s you is still surreal. I wish the game itself had as much family-friendly anarchy. Part of me wants to argue the inconsistent art direction between minigames brings this closer to WarioWare or a modern game jam, but it's just not there.

With 12 minigames of varying quality on offer, Sony's making a go at matching its competitors in silly gimmickry. A good chunk of the experience revolves around variations on whack-a-mole, or something like those Moorhuhn (Crazy Chicken) shovelware titles you see every now and then. This whole idea of pairing a novel, limited but intriguing add-on console toy with what amounts to a prototype Carnival Games worked at the time. The folks & I had a solid time looking stupid in front of the TV, though my sister stuck mostly to our metal DDR pad since those games had far more substance. Little did we know this would have us wibblin' and wobblin' in the living room some years later—that was Wii Sports, though, which remains far more replayable in 2023.

EyeToy Play is fun enough for what it is, a serviceable pack-in game which took the safe route with proving that this idea could even work. Nintendo's aforementioned handheld lens toy has somehow managed to age better by dint of offering a uniquely lo-fi experience, though. Going from harsh but exotic monochrome games and photo printing to the blurry, often out-of-focus mess EyeToy provides seems a bit underwhelming nowadays. What I really lament, though, is the C-rate Y2K aesthetic dominating this collection. (Half of the game looks like it's recycling unused Psybadek concepts, mashing them up with Gorillaz and other post-Y2K intercontinental mascot designs.) It just reminds me too much of when these developers, a mix of ex-Psygnosis fellas and The Getaway's team, had more creative projects to work on.

Again, this isn't a strictly bad game. Most minigames work properly with the EyeToy in most room settings, and it's a bit amusing to wave your arms around, a kind of bastardized ParaPara Paradise or Samba de Amigo for the new era. Just temper your expectations if you collect one of these square, googly things and stick this in your PS2. I'd personally rather play SEGA Superstars if only for the IP variety and actual Samba de Amigo experience. However, the lack of ambition and increasingly quaint presentation behind this pack-in was kind of the point. If it was too good a free disc to keep playing, would you have bought all those other EyeToy games coming later? Consider how Nintendo fell into that trap later, with Wii Sports & Play offering enough for most owners to just skip out on following minigame collections (or settle for the bargain bin equivalents).

See, this is exactly what Thursday does to an oldhead like me. I get vaguely nostalgic thoughts about what passed muster for party night amusement at the end of elementary school, and then I think harder about what this was actually like. Youngsters have it so much easier in these social media dog days. EyeToy: Play was the offline TikTok dance simulator of its day, cheaper than a ParaPara cab every weekend but not much more advanced than some plastic maracas. Games like this fall through the cracks of half-remembered cringe and convenient historic amnesia—some would say for the better. I just feel sorry for all the UK devs Sony chopped into teams like London Studio, who then had to take any mid project they could get by their corporate sponsor. tl;dr Where the hell's the Wipeout minigame in this set?!

1976

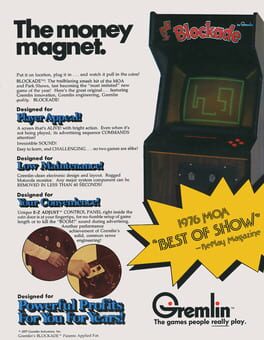

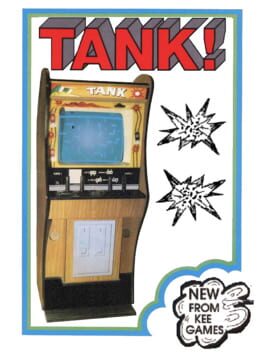

Where does the versus arcade game go after Atari's Pong or Tank? Both games stuck to the ball-and-paddle paradigm in one way or another. Blockade was the solution: turn Etch-A-Sketch into an entropic competition to fill the screen. Negative space becomes the battleground for a duel of wits and reflexes, as either player tries to snake around each other without colliding. Gremlin's "money magnet" of '76 spawned a whole genre of imitators, leading to the modern snake game as popularized on Nokia phones and the Internet.

It's funny how you can't really play the original snake game, despite its outward simplicity and ease of emulation. We think of the genre today as a single-player experience when it started in the realm of 1-on-1 coin munchers. Arcade-goers still desired the kind of simple competitive pleasures Pong had provided, just with a novel game mechanic. From the moment you and your opponent start moving, with no way to stop, there's a clear, immediate tension. You're all walled in, and you've got nowhere to go but closer to your foe.

Pong, Tank, and Spacewar! before them worked because they provided the illusion of an open space you could play in, even if you either stuck to one plane of movement or had limited room for exchanging fire. I think the genius of Blockade comes from dispelling that notion entirely. You're never in any doubt about your opportunities to corner and trick the other player. And you've always got the harsh green borders of the screen to keep you focused, mentally hemmed in by the game. Clash is inevitable in this slowly filling digital world, promising not the freedom of an open space but a ruthless drive to destruction.

Today, it all seems a bit quaint. We're many decades separated from Blockade—the progenitor of not just snake games all about managing a depleting space, but the confinement of the fighting game genre too. As fast as this must have seemed in '76, it's laborious and simply dull to play today. Indeed, Gremlin engineer Lane Hauck's creation "wasn't a good game from the standpoint of making money...The industry loved Blockade but the public yawned.". Creators like him recognized the sea change this game proved was feasible, though. It wouldn't be long before Disney's TRON demonstrated how exciting this concept could be. Moreover, Blockade's success with operators showed that Tank was no fluke, that plenty of multiplayer dueling concepts beyond the ball and paddle were not just viable, but desirable.

All in all, I can't really hold much against a game that did well enough to get clones with names like Bigfoot Bonkers. I'd have never grown up chomping down every little dot on my flip-phone LCD screen were it not for this. (Hell, where would Head-On or Pac-Man be if Blockade hadn't paved the way?!) Of their pre-SEGA achievements, Gremlin's original screen filler has earned its place in arcade game history.

It's funny how you can't really play the original snake game, despite its outward simplicity and ease of emulation. We think of the genre today as a single-player experience when it started in the realm of 1-on-1 coin munchers. Arcade-goers still desired the kind of simple competitive pleasures Pong had provided, just with a novel game mechanic. From the moment you and your opponent start moving, with no way to stop, there's a clear, immediate tension. You're all walled in, and you've got nowhere to go but closer to your foe.

Pong, Tank, and Spacewar! before them worked because they provided the illusion of an open space you could play in, even if you either stuck to one plane of movement or had limited room for exchanging fire. I think the genius of Blockade comes from dispelling that notion entirely. You're never in any doubt about your opportunities to corner and trick the other player. And you've always got the harsh green borders of the screen to keep you focused, mentally hemmed in by the game. Clash is inevitable in this slowly filling digital world, promising not the freedom of an open space but a ruthless drive to destruction.

Today, it all seems a bit quaint. We're many decades separated from Blockade—the progenitor of not just snake games all about managing a depleting space, but the confinement of the fighting game genre too. As fast as this must have seemed in '76, it's laborious and simply dull to play today. Indeed, Gremlin engineer Lane Hauck's creation "wasn't a good game from the standpoint of making money...The industry loved Blockade but the public yawned.". Creators like him recognized the sea change this game proved was feasible, though. It wouldn't be long before Disney's TRON demonstrated how exciting this concept could be. Moreover, Blockade's success with operators showed that Tank was no fluke, that plenty of multiplayer dueling concepts beyond the ball and paddle were not just viable, but desirable.

All in all, I can't really hold much against a game that did well enough to get clones with names like Bigfoot Bonkers. I'd have never grown up chomping down every little dot on my flip-phone LCD screen were it not for this. (Hell, where would Head-On or Pac-Man be if Blockade hadn't paved the way?!) Of their pre-SEGA achievements, Gremlin's original screen filler has earned its place in arcade game history.

Love Is... conceiving your son Milo Casali by artificial insemination, to the chagrin of the Vatican, and announcing this proudly in your comic strip. Love Is... the Casali sons making their own staple of pop media in a similarly simple but unexpected way.

Love Is... the Plutonia Experiment, if I might be so bold. There's nothing but love throughout this entire mapset, a perennial standout among the classic Doom games for reasons debated to this day. For 1996, the mapping designs and concepts employed in PLUTONIA.WAD were avant-garde, yet seem very obvious and simple to modern Doom players. The Casali brothers were done playing by the rules and conventions fellow fan creators were bound to, from overt attempts at realism ("DoomCute" in today's parlage) to prizing adventuring and cheap thrills over exacting endurance tests of skill. For Dario & Milo, it was now or never to challenge, even brutalize their community. A kind of tough love, perhaps.

As a fanmade map pack turned second half of Final Doom, Plutonia serves as a necessary foil to TNT: Evilution's excesses and concessions. The Casalis bros. knew their community maps well, and had already been pushing the possibilities of the pre-source port Doom engine with solo releases like PUNISHER.WAD and BUTCHER.WAD. After id software witnessed their contributions to TNT.WAD—two of the most polished maps in that whole set, Dario's "Pharaoh" and Milo's "Heck"—they met and discussed making a whole new expansion pack to feature in Final Doom. The early maps they showed American McGee quickly became the start for Plutonia, which Dario & Milo had much less time to work on than TeamTNT had for their own mapset.

I could go further into The Plutonia Experiment's history, but Doomworld and Dario's own contributions paint more of the picture already. What you should know on a first playthrough is that one cannot just like this WAD. Nearly everyone I know in the Doom fandom either loves or hates this monument to mid-'90s FPS experimentation. It's more than reasonable to run through Plutonia on a lower difficulty since the maps are well-designed to retain their intensity and skill demands on Hurt Me Plenty at least. But the Casalis built this game as the kind of Japanese game show obstacle course any Doom player in '96 would approach with caution, if not trepidation. There's no remorse, little reprieve, and relatively few dull moments anywhere throughout Plutonia's alienating, jungle-laden mess of arenas, gauntlets, and set-pieces. Tough love indeed.

Not every level hits these marks. I can list some of my own pet-hate experiences, from the very poorly telegraphed "Indiana Jones" invisible bridge in MAP02: Well of Souls, to the cramped teleporting Archvile trap wrecking first-time players in MAP12: Speed. A couple of maps utterly put me off even now, mainly MAP20: The Death Domain (too many gotchas, not enough chances to take cover) or MAP30: Gateway to Hell (another needless tradition, the Icon of Sin finale). Otherwise, that leaves us with thirty difficult but rewarding maps combining Doom II's masterful combat design with more streamlined, less noodly levels to navigate. I think it's a winning combination, even if some 1996 contemporaries like the Memento Mori II mapset showcase prettier or more conceptually ambitious works.

One thing that absolutely works in Plutonia's favor is its difficult but fair approach to most combat scenarios. This is not anything like a Mario kaizo hack or masocore gaming in general. But you'll have every reason to approach fights strategically, using the right weapons and movement at the right time to survive. Both of the brothers prefer small but uniquely lethal combinations of monsters to the giant hordes you see in many popular maps today. Economy of design defines this set in contrast to not just Evilution, but other community-made packs from the time like Memento Mori. A single archvile, a couple revenants, and some cannon fodder imps...put them in a non-trivial space to travel around and you'll have one hell of a battle!

To this end, most maps shower you in higher-tier ammo for those upper-level weapons. Expect to learn the ins and outs of rocket launcher splash damage, or how to efficiently wield the BFG's invisible tracer spread fire. Practice hard enough and you'll get a feel for how to conserve super shotgun ammo as you mow down pinkies, or the basics of redirecting skeleton fireballs into other foes to get them infighting. The Casalis weren't making hard-ass shit for the sake of being hardasses. At a time when speedrunning demos were gaining popularity and the Doom community's skills and metagame were evolving, these two just wanted to gift everyone a bloody chocolate box for Valentine's. True love waits.

Funny thing is, these maps aren't as bizarre or off-putting as one might think, at least when you realize they're clever remixes of id's own levels! It makes sense how, with only several weeks to build and test their vanilla-compatible maps largely by themselves, the Casalis would chop up useful bits from Doom I & II for their own purposes. Milo's MAP21: Slayer is an obvious riff on 'O' of Destruction and other Romero levels, for instance, while Dario's works like MAP08: Realm liberally borrow ideas from Sandy Petersen's oft-maligned creations. This does mean the set can't be as revelatory or unique as it could have, despite some memorable new ideas like the iconic archvile maze in MAP11. Still, there's plenty of clever trope reuse all throughout Plutonia that had few if any contenders in the community back then. We're a decade-and-a-half off from projects like Doom the Way id Did, after all, and these time-saving homages to the original games came in clutch for the project.

Some make this more obvious than others, like the utterly chaotic, classic slaughtermap remix of MAP01: Entryway from Doom II. This new creation, Go 2 It, even seems at odds with the spare monster placement and emphasis on precision attrition Plutonia's advocated for up until now. Hundreds of baddies swarm the bones of an opening stage best known then as the main multiplayer 1v1 map. Yet applying your newfound reflexes and reactions to enemy attacks makes the original slaughter experience not just viable, but fucking brilliant to play. All these funny lil' guys on screen are just going to kill each other anyway if you can juke them into hitting one another. Simple strategies lead to satisfying successes. It's more than just "git gud", as some will profess—more so getting flexible and adapting to scary but beatable challenges as you go.

Without Plutonia, I'm not sure I'd have ever gotten into Doom mapping, let alone a ton of newer fan creations both easier and harder than Final Doom. This feels like a necessary leap in complexity and player demands, one that's often a bit too harsh and formulaic yet well-meaning with how it challenges you. If Doom II proved that id's template was no fluke, and community efforts like Evilution and Memento Mori II showcased the story-/adventure-driven possibilities of new maps, then Plutonia's a necessary course correction for its time. The Casalis loved not just how they could push the engine to its theorized limits, but how they could maximize Romero & Petersen's game design for all its worth. What others see as unfair (which I occasionally agree with), I see as ascetic and utterly focused on avoiding downtime. There's just enough negative space in these maps between encounters to give you a breather, but never too much to bore.

Love Is... a compelling mixture, a chemical reaction that keeps you invested. It might get ugly and wear you down at times, yet it keeps you coming back. Sure it can be painful, as much as life ought not to. But if it helps you grow stronger, more understanding and empathetic, is that such a bad trade? I've had a healthy relationship with The Plutonia Experiment for years now, one which taught me make simple but effective moves in combat, or fun maps for my friends to play. This kind of appreciation takes time and effort; I won't fault anyone if they can't commit to it, and I recognize the privileges one might need to get this far. In the end, I like to think it's all been worth the patience. True love waits.

Love Is... the Plutonia Experiment, if I might be so bold. There's nothing but love throughout this entire mapset, a perennial standout among the classic Doom games for reasons debated to this day. For 1996, the mapping designs and concepts employed in PLUTONIA.WAD were avant-garde, yet seem very obvious and simple to modern Doom players. The Casali brothers were done playing by the rules and conventions fellow fan creators were bound to, from overt attempts at realism ("DoomCute" in today's parlage) to prizing adventuring and cheap thrills over exacting endurance tests of skill. For Dario & Milo, it was now or never to challenge, even brutalize their community. A kind of tough love, perhaps.

As a fanmade map pack turned second half of Final Doom, Plutonia serves as a necessary foil to TNT: Evilution's excesses and concessions. The Casalis bros. knew their community maps well, and had already been pushing the possibilities of the pre-source port Doom engine with solo releases like PUNISHER.WAD and BUTCHER.WAD. After id software witnessed their contributions to TNT.WAD—two of the most polished maps in that whole set, Dario's "Pharaoh" and Milo's "Heck"—they met and discussed making a whole new expansion pack to feature in Final Doom. The early maps they showed American McGee quickly became the start for Plutonia, which Dario & Milo had much less time to work on than TeamTNT had for their own mapset.

I could go further into The Plutonia Experiment's history, but Doomworld and Dario's own contributions paint more of the picture already. What you should know on a first playthrough is that one cannot just like this WAD. Nearly everyone I know in the Doom fandom either loves or hates this monument to mid-'90s FPS experimentation. It's more than reasonable to run through Plutonia on a lower difficulty since the maps are well-designed to retain their intensity and skill demands on Hurt Me Plenty at least. But the Casalis built this game as the kind of Japanese game show obstacle course any Doom player in '96 would approach with caution, if not trepidation. There's no remorse, little reprieve, and relatively few dull moments anywhere throughout Plutonia's alienating, jungle-laden mess of arenas, gauntlets, and set-pieces. Tough love indeed.

Not every level hits these marks. I can list some of my own pet-hate experiences, from the very poorly telegraphed "Indiana Jones" invisible bridge in MAP02: Well of Souls, to the cramped teleporting Archvile trap wrecking first-time players in MAP12: Speed. A couple of maps utterly put me off even now, mainly MAP20: The Death Domain (too many gotchas, not enough chances to take cover) or MAP30: Gateway to Hell (another needless tradition, the Icon of Sin finale). Otherwise, that leaves us with thirty difficult but rewarding maps combining Doom II's masterful combat design with more streamlined, less noodly levels to navigate. I think it's a winning combination, even if some 1996 contemporaries like the Memento Mori II mapset showcase prettier or more conceptually ambitious works.

One thing that absolutely works in Plutonia's favor is its difficult but fair approach to most combat scenarios. This is not anything like a Mario kaizo hack or masocore gaming in general. But you'll have every reason to approach fights strategically, using the right weapons and movement at the right time to survive. Both of the brothers prefer small but uniquely lethal combinations of monsters to the giant hordes you see in many popular maps today. Economy of design defines this set in contrast to not just Evilution, but other community-made packs from the time like Memento Mori. A single archvile, a couple revenants, and some cannon fodder imps...put them in a non-trivial space to travel around and you'll have one hell of a battle!

To this end, most maps shower you in higher-tier ammo for those upper-level weapons. Expect to learn the ins and outs of rocket launcher splash damage, or how to efficiently wield the BFG's invisible tracer spread fire. Practice hard enough and you'll get a feel for how to conserve super shotgun ammo as you mow down pinkies, or the basics of redirecting skeleton fireballs into other foes to get them infighting. The Casalis weren't making hard-ass shit for the sake of being hardasses. At a time when speedrunning demos were gaining popularity and the Doom community's skills and metagame were evolving, these two just wanted to gift everyone a bloody chocolate box for Valentine's. True love waits.

Funny thing is, these maps aren't as bizarre or off-putting as one might think, at least when you realize they're clever remixes of id's own levels! It makes sense how, with only several weeks to build and test their vanilla-compatible maps largely by themselves, the Casalis would chop up useful bits from Doom I & II for their own purposes. Milo's MAP21: Slayer is an obvious riff on 'O' of Destruction and other Romero levels, for instance, while Dario's works like MAP08: Realm liberally borrow ideas from Sandy Petersen's oft-maligned creations. This does mean the set can't be as revelatory or unique as it could have, despite some memorable new ideas like the iconic archvile maze in MAP11. Still, there's plenty of clever trope reuse all throughout Plutonia that had few if any contenders in the community back then. We're a decade-and-a-half off from projects like Doom the Way id Did, after all, and these time-saving homages to the original games came in clutch for the project.

Some make this more obvious than others, like the utterly chaotic, classic slaughtermap remix of MAP01: Entryway from Doom II. This new creation, Go 2 It, even seems at odds with the spare monster placement and emphasis on precision attrition Plutonia's advocated for up until now. Hundreds of baddies swarm the bones of an opening stage best known then as the main multiplayer 1v1 map. Yet applying your newfound reflexes and reactions to enemy attacks makes the original slaughter experience not just viable, but fucking brilliant to play. All these funny lil' guys on screen are just going to kill each other anyway if you can juke them into hitting one another. Simple strategies lead to satisfying successes. It's more than just "git gud", as some will profess—more so getting flexible and adapting to scary but beatable challenges as you go.

Without Plutonia, I'm not sure I'd have ever gotten into Doom mapping, let alone a ton of newer fan creations both easier and harder than Final Doom. This feels like a necessary leap in complexity and player demands, one that's often a bit too harsh and formulaic yet well-meaning with how it challenges you. If Doom II proved that id's template was no fluke, and community efforts like Evilution and Memento Mori II showcased the story-/adventure-driven possibilities of new maps, then Plutonia's a necessary course correction for its time. The Casalis loved not just how they could push the engine to its theorized limits, but how they could maximize Romero & Petersen's game design for all its worth. What others see as unfair (which I occasionally agree with), I see as ascetic and utterly focused on avoiding downtime. There's just enough negative space in these maps between encounters to give you a breather, but never too much to bore.

Love Is... a compelling mixture, a chemical reaction that keeps you invested. It might get ugly and wear you down at times, yet it keeps you coming back. Sure it can be painful, as much as life ought not to. But if it helps you grow stronger, more understanding and empathetic, is that such a bad trade? I've had a healthy relationship with The Plutonia Experiment for years now, one which taught me make simple but effective moves in combat, or fun maps for my friends to play. This kind of appreciation takes time and effort; I won't fault anyone if they can't commit to it, and I recognize the privileges one might need to get this far. In the end, I like to think it's all been worth the patience. True love waits.

Shelley Day, Ron Gilbert & co. making a cute 'lil kids adventure dominoes falling Humungous Entertainment co-founder convicted of defrauding bank to buy a dream home next door to Paul Allen

Oh, there's an actual game to talk about here, not just the sad irony of Humungous' downfall. It's just a rather simplistic experience aside from its then innovative take on the edutainment adventure. Most PC DOS & Mac software oriented towards this demographic at the time talked down to kids, rather than taking their wants and fears seriously. No more forced, obviously pedantic lessons you'd snooze through in the computer lab—Putt-Putt has an actual story to tell. And you're right in it with him, from proving your civic responsibility to homing a stray dog. It's a bit problematic in the sense that our purple funky four-wheeler mainly does this to, well, Join the Parade and all, but engaging and meaningful enough for almost any kindergartener. Just ignore how he could be saving lost puppies for its own sake. I got my start with Putt-Putt starting from the lunar sequel, but this felt oh so cozy and familiar in similar ways.

Gilbert's goals of empowering young players and avoiding condescension already show results here. The game opens with an effortless "tutorial" where Putt-Putt awakens at home and gets to toy around in the garage. It's here where you first encounter the studio's famous "click points", where seemingly mundane set dressing comes to life as you click around. Even the diegetic HUD, Putt-Putt's dashboard, has its own easter eggs, encouraging you to try interacting with anything on screen. From simple animations to complex multi-step interactions, these click points evolved from similar examples in earlier LucasArts and Cyan Worlds adventures, now used to intuitively advance the player's story by giving them a toybox of sorts.

That's really what saves this from a lower rating, as the plot is as basic and A-to-B as a Junior Adventure gets. Mowing lawns makes up the bulk of any challenge you'll find, and the puzzles couldn't be more elementary if they tried. Figuring out where to go and how to get the needed key items takes no time at all, for better or worse. This makes it a nice one-sitting game for its age group, no doubt. But the sequels add more interesting questing, click points, story sequences, etc. that Joins the Parade sorely lacks. It's the blueprint they'd all quickly surpass. I can't really poo-poo this adventure as such, nor can I rate it higher.

Can we at least talk about how uncanny Putt-Putt and his world looks in these first two MS-DOS entries? Pixel-era Humungous games had a lot of art jank, especially when characters look at the camera. Putt-Putt's proportions and facial expressions run the gamut from mildly off-model to humorously off-putting (pun intended). Some like to joke about him making a serial killer face here and in Goes to the Moon—I can totally see it. But that's also a charming reminder of the studio's beginnings, a bit before they moved to high-quality art and animation with Freddi Fish and their Windows 9x-era Junior Adventures.

What Myst did for the adult multimedia games market, Putt-Putt achieved for multimedia kids' games. This was an important step into the public eye for similar works like The Manhole, and a masterfully dialed-down, less lethal take on the point-and-click adventure during the genre's heyday. I just wish I could get more out of it nowadays, but that's what happens when you're used to the excellence of Pajama Sam or Spy Fox. Things only got more ambitious for the Junior Adventures in a short span of time, and it wasn't long before the parade left Putt-Putt's original story far behind.

Oh, there's an actual game to talk about here, not just the sad irony of Humungous' downfall. It's just a rather simplistic experience aside from its then innovative take on the edutainment adventure. Most PC DOS & Mac software oriented towards this demographic at the time talked down to kids, rather than taking their wants and fears seriously. No more forced, obviously pedantic lessons you'd snooze through in the computer lab—Putt-Putt has an actual story to tell. And you're right in it with him, from proving your civic responsibility to homing a stray dog. It's a bit problematic in the sense that our purple funky four-wheeler mainly does this to, well, Join the Parade and all, but engaging and meaningful enough for almost any kindergartener. Just ignore how he could be saving lost puppies for its own sake. I got my start with Putt-Putt starting from the lunar sequel, but this felt oh so cozy and familiar in similar ways.

Gilbert's goals of empowering young players and avoiding condescension already show results here. The game opens with an effortless "tutorial" where Putt-Putt awakens at home and gets to toy around in the garage. It's here where you first encounter the studio's famous "click points", where seemingly mundane set dressing comes to life as you click around. Even the diegetic HUD, Putt-Putt's dashboard, has its own easter eggs, encouraging you to try interacting with anything on screen. From simple animations to complex multi-step interactions, these click points evolved from similar examples in earlier LucasArts and Cyan Worlds adventures, now used to intuitively advance the player's story by giving them a toybox of sorts.

That's really what saves this from a lower rating, as the plot is as basic and A-to-B as a Junior Adventure gets. Mowing lawns makes up the bulk of any challenge you'll find, and the puzzles couldn't be more elementary if they tried. Figuring out where to go and how to get the needed key items takes no time at all, for better or worse. This makes it a nice one-sitting game for its age group, no doubt. But the sequels add more interesting questing, click points, story sequences, etc. that Joins the Parade sorely lacks. It's the blueprint they'd all quickly surpass. I can't really poo-poo this adventure as such, nor can I rate it higher.

Can we at least talk about how uncanny Putt-Putt and his world looks in these first two MS-DOS entries? Pixel-era Humungous games had a lot of art jank, especially when characters look at the camera. Putt-Putt's proportions and facial expressions run the gamut from mildly off-model to humorously off-putting (pun intended). Some like to joke about him making a serial killer face here and in Goes to the Moon—I can totally see it. But that's also a charming reminder of the studio's beginnings, a bit before they moved to high-quality art and animation with Freddi Fish and their Windows 9x-era Junior Adventures.

What Myst did for the adult multimedia games market, Putt-Putt achieved for multimedia kids' games. This was an important step into the public eye for similar works like The Manhole, and a masterfully dialed-down, less lethal take on the point-and-click adventure during the genre's heyday. I just wish I could get more out of it nowadays, but that's what happens when you're used to the excellence of Pajama Sam or Spy Fox. Things only got more ambitious for the Junior Adventures in a short span of time, and it wasn't long before the parade left Putt-Putt's original story far behind.

1982

It's the laborer's code, an allegiance to classist logic hiding behind the veneer of a machine. Who's to say you can't pull these blocks other than the rules of the game? These walls and obstacles entrap you, make you feel the claustrophobia that comes with poverty and exploitation. Surrounding these microscopic tasks are naught but void—just the fraught acceptance of capitalism's encompassing reality. Here's a gallery of A-to-Z state machines one yearns to find freedom from, yet masks the possibilities of other, better worlds beyond the transactional paradigm. A purgatory wrapped in darkness, and the only clear way forward is toiling under this system for eternity.

Even then, the original Sokoban is more than it seems. One of the final puzzles tasks you with moving blocks in a seemingly impossible way. That is, until you accidentally push through a wall, destroying a piece of it which lets you finally manipulate the block stack without failure. All future official versions of the 1982 classic would ditch this element. After all, it sounds frustrating to need to discover or know this completely un-telegraphed mechanic, doesn't it? Kind of like how your boss refuses to explain the finer details of your job, or even how to complete a seemingly simple yet elusive task? I can only imagine how the warehouse keeper must feel, hopelessly exhausting every possibility except the most absurd, contradictory one that never worked before. And it doesn't feel like an accomplishment, or a stroke of genius. You either know because someone finally told you, or you accidentally fell into success instead.

Hiroyuki Imabayashi was a retail clerk at the time he got his first computer, a Sharp MZ borrowed from a friend. The games he subsequently played on his later PC-8001 and PC-88 units, as well as an imported Apple II, inspired him to make a little game of his own, reflecting what he saw in his environment. What possessed a well-read, movie-loving record store salesman to make one of the great early pro-labor digital puzzlers? I'd like to ask him myself, though I suspect he'll answer with something like "I never thought about it that deeply". We're all so ingrained in this system of the world that we can feel its pressure and imposition as we grow ("coming of age" indeed), even if we can't always articulate that sensation. Sokoban, with all its elementary yet convoluted mind-twisters, inspires what must have seemed like a revolution in video games as introspection.

It's no surprise to me that Imabayashi soon spent way more time writing and designing graphic text adventures, most often the kinds of pulpy mysteries he grew up with. He still relies on the perennial success of Sokoban's design concept for his livelihood, but in doing so has found time and space in life to just be. What he'd created from a working man's understanding of his favorite childhood card games had forever altered game design for a post-modern era. How does one surpass that? So he moved laterally, handing the reigns of commercial ambition to others at the studio he started in Takarazuka. And Thinking Rabbit certainly did experiment, yet the founder and his co-workers now work for Falcon Co., having sold their company and IPs to a former contractor following the Japan's economic and investment stagnation in the '90s. What keeps them going is, of course, a certain block-pushing Ship of Theseus most often starring some wide-eyed young man trying to buy a car or woo his love, among other bootstraps window dressing.

While Imabayashi's adventure games gained a notable following for years to come, his debut game has long since evolved beyond what he'd been able to match. Why work to reinvent that which will forever morph to other designers' wills, or just slot into myriads of other frameworks as shown by creations like Baba is You? Yet for all the appreciation Imabayashi's earned for his post-Sokoban legacy, the software which freed him has ironically trapped his image in amber. Block puzzles in video games are just too useful and universal—so the death of the author continues. I can go on my mobile app storefront of choice and find a seemingly endless number of Sokoban clones, many from first-time developers learning to code games. There's a whole cottage industry of bedroom coders building off what this once fanciful PC-8801 experiment started. And he knows all too well what it's done for him and shackled him to in the process.

I suppose this florid look at a generally self-explanatory media artifact isn't helping much. Then again, my lack of Japanese language skills makes it hard to dig into Thinking Rabbit's adventures without duress. Sokoban has become a staple of gaming across the world, spanning ages before and after its origins. We're as familiar with its principles, iterations, and insinuations as we are with backgammon or chess! And just as those pastimes silently teach lessons and etiquette pertaining to the social-economic structures birthing them, Sokoban too reflects its environment. This game ran on everything, in even more forms than Doom. It arguably had a predecessor in Nob Yoshigahara's Rush Hour puzzle, and even the lowliest of early digital handhelds like Epoch's Game Pocket Computer featured the block pusher. Ubiquity both made and destroyed Sokoban as an essential distillation of logic challenges previously fragmented across many arcade, computer, and board games the world over.

Takurazuka's greatest software creation gave players the illusion of control over time-space puzzles previously meant to eat quarters in game centers. It transferred the traditions of puzzle boxes and transfixing toys into binary. And from this black box of restrictions, revelations, and repetition comes the final realization: Sokoban invokes a wager of faith for or against capitalist reality. Those who succeed in unraveling or merely memorizing these menial tasks can feel at least a little vindicated. Those who fail will quickly realize the futility and fruitlessness of labor you give but can never keep, even if they eventually succeed under the circumstances. Everyone who's ever complained about "unfun" box pushing in a Zelda game could relate to this. All those who criticized and/or continue to lambast the likes of Papers, Please should consider the power of games as simple as this to provoke praxis in this festering world.

Maybe the most actionable thoughts Sokoban leads to now are playing a different, more fun and accessible game. We're so accustomed to what this PC-88 classic offers, and binds us to, that it's nothing worth investing time in. In this sense, Imabayashi's folly has become the kind of effortless un-game or anti-game others try too hard to sell us on. There's nothing glamorous, fantastic, or conventionally laudable about pure, unadorned Sokoban. It's too good at what it does, meaning its spiritual successors must imagine more creative, more engrossing variations on its themes. Hell, the whole idea of Baba is You can basically boil down to "what if we challenged the player to make a new Sokoban game in every single level?". Sokoban transcended its mere game-ness long ago; today it's both a platform and a bad example to follow. More than most "classic" games, this one has morphed into an idol of ludological dreams, nightmares, and ambitions subservient to the possible. Sisyphus would be proud.

For all the ramblings and minutiae I could go on about, I think you should try the original Sokoban and come to your own conclusions. The PC-88 game and its ports certainly show their age, but also how timeless they remain. Without factoring all of what Sokoban was, is, and will be into any discussion of Japanese PC software and beyond, any history of puzzle genres and tropes will be incomplete. Thank you for coming to my TED talk.

Even then, the original Sokoban is more than it seems. One of the final puzzles tasks you with moving blocks in a seemingly impossible way. That is, until you accidentally push through a wall, destroying a piece of it which lets you finally manipulate the block stack without failure. All future official versions of the 1982 classic would ditch this element. After all, it sounds frustrating to need to discover or know this completely un-telegraphed mechanic, doesn't it? Kind of like how your boss refuses to explain the finer details of your job, or even how to complete a seemingly simple yet elusive task? I can only imagine how the warehouse keeper must feel, hopelessly exhausting every possibility except the most absurd, contradictory one that never worked before. And it doesn't feel like an accomplishment, or a stroke of genius. You either know because someone finally told you, or you accidentally fell into success instead.

Hiroyuki Imabayashi was a retail clerk at the time he got his first computer, a Sharp MZ borrowed from a friend. The games he subsequently played on his later PC-8001 and PC-88 units, as well as an imported Apple II, inspired him to make a little game of his own, reflecting what he saw in his environment. What possessed a well-read, movie-loving record store salesman to make one of the great early pro-labor digital puzzlers? I'd like to ask him myself, though I suspect he'll answer with something like "I never thought about it that deeply". We're all so ingrained in this system of the world that we can feel its pressure and imposition as we grow ("coming of age" indeed), even if we can't always articulate that sensation. Sokoban, with all its elementary yet convoluted mind-twisters, inspires what must have seemed like a revolution in video games as introspection.

It's no surprise to me that Imabayashi soon spent way more time writing and designing graphic text adventures, most often the kinds of pulpy mysteries he grew up with. He still relies on the perennial success of Sokoban's design concept for his livelihood, but in doing so has found time and space in life to just be. What he'd created from a working man's understanding of his favorite childhood card games had forever altered game design for a post-modern era. How does one surpass that? So he moved laterally, handing the reigns of commercial ambition to others at the studio he started in Takarazuka. And Thinking Rabbit certainly did experiment, yet the founder and his co-workers now work for Falcon Co., having sold their company and IPs to a former contractor following the Japan's economic and investment stagnation in the '90s. What keeps them going is, of course, a certain block-pushing Ship of Theseus most often starring some wide-eyed young man trying to buy a car or woo his love, among other bootstraps window dressing.

While Imabayashi's adventure games gained a notable following for years to come, his debut game has long since evolved beyond what he'd been able to match. Why work to reinvent that which will forever morph to other designers' wills, or just slot into myriads of other frameworks as shown by creations like Baba is You? Yet for all the appreciation Imabayashi's earned for his post-Sokoban legacy, the software which freed him has ironically trapped his image in amber. Block puzzles in video games are just too useful and universal—so the death of the author continues. I can go on my mobile app storefront of choice and find a seemingly endless number of Sokoban clones, many from first-time developers learning to code games. There's a whole cottage industry of bedroom coders building off what this once fanciful PC-8801 experiment started. And he knows all too well what it's done for him and shackled him to in the process.

I suppose this florid look at a generally self-explanatory media artifact isn't helping much. Then again, my lack of Japanese language skills makes it hard to dig into Thinking Rabbit's adventures without duress. Sokoban has become a staple of gaming across the world, spanning ages before and after its origins. We're as familiar with its principles, iterations, and insinuations as we are with backgammon or chess! And just as those pastimes silently teach lessons and etiquette pertaining to the social-economic structures birthing them, Sokoban too reflects its environment. This game ran on everything, in even more forms than Doom. It arguably had a predecessor in Nob Yoshigahara's Rush Hour puzzle, and even the lowliest of early digital handhelds like Epoch's Game Pocket Computer featured the block pusher. Ubiquity both made and destroyed Sokoban as an essential distillation of logic challenges previously fragmented across many arcade, computer, and board games the world over.

Takurazuka's greatest software creation gave players the illusion of control over time-space puzzles previously meant to eat quarters in game centers. It transferred the traditions of puzzle boxes and transfixing toys into binary. And from this black box of restrictions, revelations, and repetition comes the final realization: Sokoban invokes a wager of faith for or against capitalist reality. Those who succeed in unraveling or merely memorizing these menial tasks can feel at least a little vindicated. Those who fail will quickly realize the futility and fruitlessness of labor you give but can never keep, even if they eventually succeed under the circumstances. Everyone who's ever complained about "unfun" box pushing in a Zelda game could relate to this. All those who criticized and/or continue to lambast the likes of Papers, Please should consider the power of games as simple as this to provoke praxis in this festering world.

Maybe the most actionable thoughts Sokoban leads to now are playing a different, more fun and accessible game. We're so accustomed to what this PC-88 classic offers, and binds us to, that it's nothing worth investing time in. In this sense, Imabayashi's folly has become the kind of effortless un-game or anti-game others try too hard to sell us on. There's nothing glamorous, fantastic, or conventionally laudable about pure, unadorned Sokoban. It's too good at what it does, meaning its spiritual successors must imagine more creative, more engrossing variations on its themes. Hell, the whole idea of Baba is You can basically boil down to "what if we challenged the player to make a new Sokoban game in every single level?". Sokoban transcended its mere game-ness long ago; today it's both a platform and a bad example to follow. More than most "classic" games, this one has morphed into an idol of ludological dreams, nightmares, and ambitions subservient to the possible. Sisyphus would be proud.

For all the ramblings and minutiae I could go on about, I think you should try the original Sokoban and come to your own conclusions. The PC-88 game and its ports certainly show their age, but also how timeless they remain. Without factoring all of what Sokoban was, is, and will be into any discussion of Japanese PC software and beyond, any history of puzzle genres and tropes will be incomplete. Thank you for coming to my TED talk.

2001

Frank Welker & Jason Marsden goof off as Lennie & George on cartoon-ium for a couple hours and some folks just loathe this game? I'd hate to be y'all.

Usually I wouldn't hesitate to give this a flat 2-and-a-half stars rating. It's a blatantly unfinished, underbaked game based on a promising concept that's hard to do right. Think back to A Boy and His Blob, or another finicky partner-based puzzle platformer with loads of personality. When cute and/or funny characters chafe against a mediocre or simply bad game loop, that's enough of a put-off to get the whole genre condemned. (Ironic, given how the Floigan's property could actually be condemned, what with spiders on the lot and a blue-blooded realtor swooping in to snag the joint.) So it's unsurprising that Floigan Bros. has become the object of ridicule, both light and serious, in today's retro streaming landscape. So I'm gonna be a bit nice to this doomed duo, the Stolar-approved console mascots no one wanted.

Consider, though, how much this game just doesn't care whether you like, dislike, love, or hate it. Sometimes you just need Two Men. They're two himbos, they're loony, and they'll do what they want. Yes, their flaws are strong, but their irreverence is stronger. They've been critically neglected for over 22 years. Of course there have been bugs and jank, but they always come to terms with their differences because games like this comes once in a console's lifetime. By playing Floigan Bros. you will receive not just the Marx Brothers-ness of their antics, but the weirdness of the game's history as well.no apologies for the copypasta

Knowing anything, the game's original creator, ex-Bubsy voice actor Brian Silva, has too many horror stories about getting it into production. Floigan Bros. started life as an ill-fated attempt to recreate the glory days of Laurel & Hardy or the Three Stooges for a modern gamer audience. Accolade did some pre-production for it as a PlayStation game to release in 1996, but that company's decline led to the game's hiatus until SEGA & Visual Concepts picked up Silva's pitch. Mind you, the latter studio mainly created the Dreamcast's best known sports games, from NFL 2K to Ooga Booga (yeah, that's a stretch, but online minigames can get competitive!). Back in the 16-bit console era, though, VC had done a couple of their own puzzly, platformer-y games with mixed success. Them working on this previously abandoned Marx Brothers-esque pastiche wasn't so out of place after all. The original 1995 design document showed a lot of confidence already.

Just one look at that nutty cover art, and what you can actually do in this piece of interactive media, seems beyond belief. It's half puzzle platformer, half minigame collection, all with a coat of cheesy, unironic '40s Hollywood ham and humor. Hoigle & Moigle would fit right into a Termite Terrace parody of the popular comedy double-acts from that period. And the Of Mice and Men comparison is hardly unfounded. Moigle's soft spot for woodland critters isn't far removed from Lennie's fatal love for bunnies. There's something of a dark undercurrent at play here, from the Rocky & Bullwinkle-esque villainy threatening the brothers, to the uncanny spiders you teach Moigle to finally ground-pound despite his fears.

Kooky jokes and jukes define Hoigle & Moigle's daily life. The minigames and emotion system both play into the characters' expressiveness, and I almost always have a smile or sensible chuckle at what they're doing. Sure, most of this game's simple and easy to blaze through, almost simplistic with its riddles and sidekick manipulation. And the brownie points grind needed just to teach Moigle critical skills pads out the runtime more than I'd like. But it makes for a quaint pick-up-and-play experience which perfectly fits what the developers went for. I also get a kick out of chasing down magpies, screwing with Moigle's pathfinding during tag, and the musical transitions tied to his changing moods.

Realistically, this game's release was always a long shot. It took the efforts of Visual Concept's skeleton crew, led by Andy Ashcraft (War of the Monsters, PS2) and help from ex-Sonic designer Hirokazu Yasuhara, to get this out late in the Dreamcast's life. And while this technically pioneered or at least promised the episodic game format we know today, it only ever received a smattering of minor DLC add-ons which didn't see the light of day until last decade! This arguably might have done better if SEGA promoted it to an enhanced XBOX release, but having that last-minute platform exclusive clearly mattered more. This all explains the game's relative lack of content and playtime vs. what you would have payed back in the day. DC owners probably overlooked the price-to-value ratio just because any exclusive this interesting was worth the money then, though.

Obscure as it is, Floigan Bros. continues to entice and beguile all but the most hardy of classic game fans. Jerma, WayneRadioTV, and other streamers can't help but poke and prod at the game for a bemused audience. The few speedrunners I've seen playing this have their own commentary on it, often pointing out the somewhat buggy, janky programming you'll notice. For me, this remains one of the most interesting examples of SEGA's swan song ambitions. It hails from a time when the Dreamcast hosted all kinds of design experiments, from the successful (Shenmue, Jet Set Radio) to the forgotten (Headhunter, OutTrigger). Something told me there was more to this game than most would consider, given its "mid"-ness. I vaguely recall browsing the original SEGA website for it, confused by the classic American film humor and references but intrigued regardless.

What's one to do when an adventure in game development this unusual has so little coverage outside of memes? I had my own solution back in high school (Fall 2011, start of my junior year). After learning about designer Andy Ashcraft's role in fleshing out and finishing Floigan Bros., I e-mailed him some questions and thankfully got a considerate reply. Silva's been interviewed about the game recently, but I'd like to ask Yasuhara and other ex-devs some questions before compiling these primary comments into a fully-fledged retrospective. What I learned from Ashcraft alone tells me how much of a labor of love this game became.

Likely because Yasuhara came into the project very late, Ashcraft didn't have a lot to share about working with him, other than having a strong working relationship. Visual Concepts mainly started making the game back in '97, led by studio head Scott Patterson and a newly-recruited Ashcraft. The first problem they encountered was how to naturally integrate everything about Moigle into an accessible game loop. As I learned in the email chain, the big galoot had to be "somewhat unpredictable and be able to (or seem to) make decisions on his own about what to do and when to do it". On the other hand, VC considered how Moigle needed to "know what the player is wanting to do at all times, especially in tight life-or-death situations". They swiftly abandoned the do-or-die part, going for a less stressful set of puzzles and sequences which players could better manage.

In every part of the game's environments, the devs placed "distraction points" that Moigle responds to, a veritable sheep to your shepherd. It's easy for players to notice how the chatty, scheming cat-tagonist laps up Moigle's attention when nearby. Same goes for the aforementioned spiders, being one of the few entities strong enough to wreck his mood. Tweaking all these fragile variables, often with only one programmer available due to VC focusing on sports games (and talented staff leaving for greener pastures), greatly delayed production. It's a small miracle the game came out at all, even as Ashcraft and then Yasuhara had plenty of time to design it. Production woes aside, the former designer still considers this project an early triumph in building a game around a relatively natural, lively AI character dynamics...better than contemporaries like Daikatana, anyway.

Nothing like this existed on consoles at the time. Even the PlayStation port of the original Creatures wouldn't release until 2002, so almost a year after. Sure, you could argue that Chao raising in the Sonic Adventure games was close enough, but combining a learning AI with simple but elaborate world-puzzle progression was no mean feat. It's debatable how fun this actually is as a concept, but I'm far from deeming this as odd shovelware the way some do. Floigan Bros. has a lot of body and soul you can still experience, even without the historic context (though that helps!). Its mini-games are short enough to never get on my nerves—most are at least a little fun—and the junkyard possesses a palpable sekaikan, that lived-in verisimilitude which brings this beyond mere slapstick. This could have aged a bit better graphically, but the excellent animations and Jazz Age soundtrack feels like an early go at what games like Cuphead have accomplished recently. Tons to appreciate, overall.

Give the Floigan Bros. experience a shot, people! Maybe I'm a lot softer towards this than I should be, and I won't argue against anyone pointing out the jank or how it feels like a misbegotten Amiga-era oddity. But it still feels like too many rush to judge this one as harshly as I've seen. Few vaporware games emerge from their pupa into anything this polished, especially towards the end of a troubled console's lifecycle. Even fewer tackle a style of humor and homage this unattractive yet admirable, then or now. There's still a lot of room in the indie space for throwback Depression-era comedy games, something Floigan Bros. doesn't exactly nail either. The game's just too funny, replayable, and earnest for me to rag on, and we're still discovering neat parts of it today, from developer histories to previously-lost DLC. It's a relevant part of not just the Dreamcast's legacy, but the tales behind many decorated game developers. Plus it's got Fred from Scooby-Doo playing one of his all-time great Scrimblo roles, so what's not to love?

Fuck, maybe I'm just Floigan pilled after all.

Usually I wouldn't hesitate to give this a flat 2-and-a-half stars rating. It's a blatantly unfinished, underbaked game based on a promising concept that's hard to do right. Think back to A Boy and His Blob, or another finicky partner-based puzzle platformer with loads of personality. When cute and/or funny characters chafe against a mediocre or simply bad game loop, that's enough of a put-off to get the whole genre condemned. (Ironic, given how the Floigan's property could actually be condemned, what with spiders on the lot and a blue-blooded realtor swooping in to snag the joint.) So it's unsurprising that Floigan Bros. has become the object of ridicule, both light and serious, in today's retro streaming landscape. So I'm gonna be a bit nice to this doomed duo, the Stolar-approved console mascots no one wanted.

Consider, though, how much this game just doesn't care whether you like, dislike, love, or hate it. Sometimes you just need Two Men. They're two himbos, they're loony, and they'll do what they want. Yes, their flaws are strong, but their irreverence is stronger. They've been critically neglected for over 22 years. Of course there have been bugs and jank, but they always come to terms with their differences because games like this comes once in a console's lifetime. By playing Floigan Bros. you will receive not just the Marx Brothers-ness of their antics, but the weirdness of the game's history as well.

Knowing anything, the game's original creator, ex-Bubsy voice actor Brian Silva, has too many horror stories about getting it into production. Floigan Bros. started life as an ill-fated attempt to recreate the glory days of Laurel & Hardy or the Three Stooges for a modern gamer audience. Accolade did some pre-production for it as a PlayStation game to release in 1996, but that company's decline led to the game's hiatus until SEGA & Visual Concepts picked up Silva's pitch. Mind you, the latter studio mainly created the Dreamcast's best known sports games, from NFL 2K to Ooga Booga (yeah, that's a stretch, but online minigames can get competitive!). Back in the 16-bit console era, though, VC had done a couple of their own puzzly, platformer-y games with mixed success. Them working on this previously abandoned Marx Brothers-esque pastiche wasn't so out of place after all. The original 1995 design document showed a lot of confidence already.

Just one look at that nutty cover art, and what you can actually do in this piece of interactive media, seems beyond belief. It's half puzzle platformer, half minigame collection, all with a coat of cheesy, unironic '40s Hollywood ham and humor. Hoigle & Moigle would fit right into a Termite Terrace parody of the popular comedy double-acts from that period. And the Of Mice and Men comparison is hardly unfounded. Moigle's soft spot for woodland critters isn't far removed from Lennie's fatal love for bunnies. There's something of a dark undercurrent at play here, from the Rocky & Bullwinkle-esque villainy threatening the brothers, to the uncanny spiders you teach Moigle to finally ground-pound despite his fears.

Kooky jokes and jukes define Hoigle & Moigle's daily life. The minigames and emotion system both play into the characters' expressiveness, and I almost always have a smile or sensible chuckle at what they're doing. Sure, most of this game's simple and easy to blaze through, almost simplistic with its riddles and sidekick manipulation. And the brownie points grind needed just to teach Moigle critical skills pads out the runtime more than I'd like. But it makes for a quaint pick-up-and-play experience which perfectly fits what the developers went for. I also get a kick out of chasing down magpies, screwing with Moigle's pathfinding during tag, and the musical transitions tied to his changing moods.

Realistically, this game's release was always a long shot. It took the efforts of Visual Concept's skeleton crew, led by Andy Ashcraft (War of the Monsters, PS2) and help from ex-Sonic designer Hirokazu Yasuhara, to get this out late in the Dreamcast's life. And while this technically pioneered or at least promised the episodic game format we know today, it only ever received a smattering of minor DLC add-ons which didn't see the light of day until last decade! This arguably might have done better if SEGA promoted it to an enhanced XBOX release, but having that last-minute platform exclusive clearly mattered more. This all explains the game's relative lack of content and playtime vs. what you would have payed back in the day. DC owners probably overlooked the price-to-value ratio just because any exclusive this interesting was worth the money then, though.

Obscure as it is, Floigan Bros. continues to entice and beguile all but the most hardy of classic game fans. Jerma, WayneRadioTV, and other streamers can't help but poke and prod at the game for a bemused audience. The few speedrunners I've seen playing this have their own commentary on it, often pointing out the somewhat buggy, janky programming you'll notice. For me, this remains one of the most interesting examples of SEGA's swan song ambitions. It hails from a time when the Dreamcast hosted all kinds of design experiments, from the successful (Shenmue, Jet Set Radio) to the forgotten (Headhunter, OutTrigger). Something told me there was more to this game than most would consider, given its "mid"-ness. I vaguely recall browsing the original SEGA website for it, confused by the classic American film humor and references but intrigued regardless.

What's one to do when an adventure in game development this unusual has so little coverage outside of memes? I had my own solution back in high school (Fall 2011, start of my junior year). After learning about designer Andy Ashcraft's role in fleshing out and finishing Floigan Bros., I e-mailed him some questions and thankfully got a considerate reply. Silva's been interviewed about the game recently, but I'd like to ask Yasuhara and other ex-devs some questions before compiling these primary comments into a fully-fledged retrospective. What I learned from Ashcraft alone tells me how much of a labor of love this game became.

Likely because Yasuhara came into the project very late, Ashcraft didn't have a lot to share about working with him, other than having a strong working relationship. Visual Concepts mainly started making the game back in '97, led by studio head Scott Patterson and a newly-recruited Ashcraft. The first problem they encountered was how to naturally integrate everything about Moigle into an accessible game loop. As I learned in the email chain, the big galoot had to be "somewhat unpredictable and be able to (or seem to) make decisions on his own about what to do and when to do it". On the other hand, VC considered how Moigle needed to "know what the player is wanting to do at all times, especially in tight life-or-death situations". They swiftly abandoned the do-or-die part, going for a less stressful set of puzzles and sequences which players could better manage.