PasokonDeacon

1978

Nishikado's foundational arcade shoot-em-up continues to vex and perplex. For instance, we still don't know for sure if the game's popularity in Japan's "invader houses" did or didn't precipitate a 100-yen coin shortage. Only word of mouth (aka community legend) suggests the famous 5-rows-1-straggler technique, an early in-game secret, came from the Nagoya area. The designer-programmer himself has openly talked about the game's development over time, but internal documents from Taito may never surface, leaving out part of the picture. Compare this fragmented history to that of Pong, whose creation, proliferation, and sustained legacy is well-recorded in so many ways. For the Western gaming world, Space Invaders might as well be that Unidentified Foreign Object of desire. It drones, it transforms, and it dislocates your imagination.

I've played a comical number of Invaders clones over the past few days, all part of playing through the quote-unquote Golden Age arcade gaming pantheon. There's a lot of clunkers, but some impressive iterations too. None of them, aside from standouts like Galaga or Moon Cresta, match the elegance and entrancing rhythm the original achieved. I also can't think of any with a scoring strategy as risky yet rewarding as the Nagoya Shot, which proved this early that 1 coin's all you need to play forever—or die trying.

For all its simplicity, how did Space Invaders manage to trounce its increasingly complex, flashier competitors? Nishikado himself has his answers. He saw this work as a necessary answer to Breakout, a game where "you couldn’t advance to the next stage until you’d destroyed every block," whereas "previous games didn’t have that “all clear” concept". To make said blocks more than a passive threat, they needed their own projectiles, their own player-like identity you could immediately sense. What we see as barebones today was a major jump in difficulty and complexity then, so much that Taito sidelined the game as long as they could until it went viral. Let's also consider Nishikado's involvement in his high school magic club, or how overqualified he was at Taito in the first place, doing mechanical and electrical engineering (then computer science) at a level none could match.

All of this tells me Space Invaders had a sheer presence of genius behind it from Day 1. The clones, successors, and paradigm shifters building from it would have their day in the sun, but the Invaders Boom lasted much longer than anyone could have anticipated. As said with Pong, it's like talking about air—you can't breathe without it. Between the game's primal hide-and-seek appeal, the Nagoya & Rainbow strategies, and urban myths about it persisting through today, playing it now still feels like an experience, not just a digital toy. Everything came together at the right time & place, using the right microprocessor technology, all within the era of Star Wars and pulp science-fantasy going through a popular revival.

Playing on an original North American or Japanese cabinet today is only going to become more difficult. I can make do with MAME, and we've all played some form of this game through cultural osmosis at the least. But there's more to it than nostalgia. The people's history of Space Invaders, from garish Flynn's Arcade near the bar, to smoky late-night hours on cocktail cabs in Tokyo—and all other variations—has never stopped, never reached a fabled end. It lives on at barcades, gaming conventions, online streams, and awards shows. The alien specter looms over everyone in some welcoming way, as if to say video games are here to stay. Galaxian might give me more to sink my teeth into, but it'll struggle to fascinate the way Nishikado's game can.

I'm not going to pretend my 4-star rating isn't a little biased, especially for a game I talk about more than I play. But it'd be weird to knock it down a peg just because other developers made better works off its foundation over time. Fact is, the game held its own for nearly three years, only dethroned internationally the likes of Scramble, Xevious, Star Force, and Gradius. And all their creators cited Invaders as the one to beat, of course. If Pong & Breakout proved that video games could work in an era of electromechanical hegemony, then Invaders showed what videos games could evoke beyond mere amusement. Its level of challenge, economy of action, and framing of conflict shattered so many expectations across the industry. Whole clubs, fanzines, and publications sprouted up around it like the beginnings of a religion. The game's reality distortion field is strong to this day, enough to surpass its own design qualities. What else can I say?

I've played a comical number of Invaders clones over the past few days, all part of playing through the quote-unquote Golden Age arcade gaming pantheon. There's a lot of clunkers, but some impressive iterations too. None of them, aside from standouts like Galaga or Moon Cresta, match the elegance and entrancing rhythm the original achieved. I also can't think of any with a scoring strategy as risky yet rewarding as the Nagoya Shot, which proved this early that 1 coin's all you need to play forever—or die trying.

For all its simplicity, how did Space Invaders manage to trounce its increasingly complex, flashier competitors? Nishikado himself has his answers. He saw this work as a necessary answer to Breakout, a game where "you couldn’t advance to the next stage until you’d destroyed every block," whereas "previous games didn’t have that “all clear” concept". To make said blocks more than a passive threat, they needed their own projectiles, their own player-like identity you could immediately sense. What we see as barebones today was a major jump in difficulty and complexity then, so much that Taito sidelined the game as long as they could until it went viral. Let's also consider Nishikado's involvement in his high school magic club, or how overqualified he was at Taito in the first place, doing mechanical and electrical engineering (then computer science) at a level none could match.

All of this tells me Space Invaders had a sheer presence of genius behind it from Day 1. The clones, successors, and paradigm shifters building from it would have their day in the sun, but the Invaders Boom lasted much longer than anyone could have anticipated. As said with Pong, it's like talking about air—you can't breathe without it. Between the game's primal hide-and-seek appeal, the Nagoya & Rainbow strategies, and urban myths about it persisting through today, playing it now still feels like an experience, not just a digital toy. Everything came together at the right time & place, using the right microprocessor technology, all within the era of Star Wars and pulp science-fantasy going through a popular revival.

Playing on an original North American or Japanese cabinet today is only going to become more difficult. I can make do with MAME, and we've all played some form of this game through cultural osmosis at the least. But there's more to it than nostalgia. The people's history of Space Invaders, from garish Flynn's Arcade near the bar, to smoky late-night hours on cocktail cabs in Tokyo—and all other variations—has never stopped, never reached a fabled end. It lives on at barcades, gaming conventions, online streams, and awards shows. The alien specter looms over everyone in some welcoming way, as if to say video games are here to stay. Galaxian might give me more to sink my teeth into, but it'll struggle to fascinate the way Nishikado's game can.

I'm not going to pretend my 4-star rating isn't a little biased, especially for a game I talk about more than I play. But it'd be weird to knock it down a peg just because other developers made better works off its foundation over time. Fact is, the game held its own for nearly three years, only dethroned internationally the likes of Scramble, Xevious, Star Force, and Gradius. And all their creators cited Invaders as the one to beat, of course. If Pong & Breakout proved that video games could work in an era of electromechanical hegemony, then Invaders showed what videos games could evoke beyond mere amusement. Its level of challenge, economy of action, and framing of conflict shattered so many expectations across the industry. Whole clubs, fanzines, and publications sprouted up around it like the beginnings of a religion. The game's reality distortion field is strong to this day, enough to surpass its own design qualities. What else can I say?

2011

Quadrupedal horses gallop down the derby, each performing their own dressage. A blue sky the Greeks would deny carpets every horizon. You wrench the stick every which way, hoping to drift into pole position. First came the crooked oval—then those canyons of pleasure—now into a motor metropolis. That which pollutes the planet now powers you through turns, collisions, spinouts, and victories. It's all too human, all too sublime.

The world no longer needs NASCAR. It's a vestigial organ of the North American auto-infrastructural complex, the enemy of a sustainable society. Hundreds of thousands squeeze into bleachers just to see drivers bailing and crashing in-between stretches of predictable slipstreaming. Why bother when, all the way back in 1993, SEGA extracted all the essential fun you could have with stock car racing? And they made it better, too!

Daytona USA was to NASCAR games what Hot Shots Golf did for, well, golf. Toshihiro Nagoshi's team at AM2 did their research on the sport, but instead chose to recreate the excitement one hopes in this kind of racing. Two racecars and three courses sounds like not nearly enough to keep you hooked, but the depth of this game's controls, stage design, and time-attack challenge never fail me. Here was an arcade revelation, transcending coin-feeding without losing the "one more try!" addictiveness of its predecessors.

Not to say Ridge Racer was that much less compelling, however. Both SEGA and Namco competed to make the best possible tech-pushing arcade racers, followed by rivals Taito and Konami. And this resulted in so many eminently replayable classics, from Battle Gear to GTI Club. Yet SEGA's 1993 debut for their Model 2 hardware outdid nearly all its challengers for years to come. I can't stress enough how simple yet skill-demanding the downshift drifting in this game and sequel is. That harsh turn towards the end of the Beginner track has upset so many eight-player races over the years. The Advanced run covers the whole gamut of driving lines and dubious PIT maneuvers. Sliding around the Expert course evokes the bliss of commanding a lead at Watkins Glen and other Actually Interesting NASCAR Races. Mastering these mechanics brings tangible rewards, and the ceiling for superior times and skill seems endless.

On top of how well it plays, Daytona USA's sights and sounds are somehow timeless in a sea of dated 3D contemporaries. (Again, something Ridge Racer excels at too.) How many times have I read "blue skies in games" with regards to Daytona and other SEGA classics? Who hasn't once sung along with Takenobu Mitsuyoshi's delightfully sampled songs while playing or in the shower? The vibrant colors, chunky but endearing texturing, and elegant shapes on-screen mesh so well with all the cheesy, life-affirming music and rumbling in your ears. Compared to the diminishing returns of today's triple-A games, this was and remains a paradigm shift in what I'd consider top-end, the confluence of price and immersion.

SEGA's had a hard time keeping this monumental game in circulation over the years, sadly. That license ain't cheap, and neither is porting the game to newer systems. I'm glad the PS3/X360 remaster could happen, even if it's unavailable to buy today. (Beats me why they haven't put the non-licensed Sega Racing Classic version up on storefronts; at least the 360 version is BC ready.) AM2's port team did as excellent a job as they could under what I'd speculate was a limited time & budget. Image quality's crisp, controls map naturally to dual-analog gamepads, and they managed to slot some useful bonus modes in for content-needy home players like myself.

Karaoke mode explains itself: you simply play through a race like normal, but trading out Mitsuyoshi vocals for on-screen lyrics. I know what mode I'm using when the gang and I load this up in VC. Then there's Challenge mode, which introduces new players to concepts like racing lines and shift drifting. I loved going through these even as an experience player; their brief nature lends well to retries. Sure, I'd have loved to race on entirely new tracks made in the original's style, but I also know how previous versions sporting those made compromises in playability or performance. That seems to be a curse for the more content-rich SEGA racers, something Namco avoided for much longer. Still, there's much to enjoy here beyond the arcade mode.

Playing Daytona today should be a lot easier than it is. I hope SEGA sees the adoration this game's had over the past decade. Any chance of them relicensing the HD release for recent platforms, or just porting Sega Racing Classic to avoid the fees, would be awesome. Until then, sailing the blue seas under blue skies is always an option. Any local (b)arcade with a twin or eight-player cab is great, too, assuming they've been maintaining it. This game's too important in arcade history to let slip into unavailability!

So what are you waiting for? We should all be rolling under blue blue skies, playing fun soundbites on the name entry table, and nailing those U-turns around tough corners. Just don't go and lose your sponsors!

The world no longer needs NASCAR. It's a vestigial organ of the North American auto-infrastructural complex, the enemy of a sustainable society. Hundreds of thousands squeeze into bleachers just to see drivers bailing and crashing in-between stretches of predictable slipstreaming. Why bother when, all the way back in 1993, SEGA extracted all the essential fun you could have with stock car racing? And they made it better, too!

Daytona USA was to NASCAR games what Hot Shots Golf did for, well, golf. Toshihiro Nagoshi's team at AM2 did their research on the sport, but instead chose to recreate the excitement one hopes in this kind of racing. Two racecars and three courses sounds like not nearly enough to keep you hooked, but the depth of this game's controls, stage design, and time-attack challenge never fail me. Here was an arcade revelation, transcending coin-feeding without losing the "one more try!" addictiveness of its predecessors.

Not to say Ridge Racer was that much less compelling, however. Both SEGA and Namco competed to make the best possible tech-pushing arcade racers, followed by rivals Taito and Konami. And this resulted in so many eminently replayable classics, from Battle Gear to GTI Club. Yet SEGA's 1993 debut for their Model 2 hardware outdid nearly all its challengers for years to come. I can't stress enough how simple yet skill-demanding the downshift drifting in this game and sequel is. That harsh turn towards the end of the Beginner track has upset so many eight-player races over the years. The Advanced run covers the whole gamut of driving lines and dubious PIT maneuvers. Sliding around the Expert course evokes the bliss of commanding a lead at Watkins Glen and other Actually Interesting NASCAR Races. Mastering these mechanics brings tangible rewards, and the ceiling for superior times and skill seems endless.

On top of how well it plays, Daytona USA's sights and sounds are somehow timeless in a sea of dated 3D contemporaries. (Again, something Ridge Racer excels at too.) How many times have I read "blue skies in games" with regards to Daytona and other SEGA classics? Who hasn't once sung along with Takenobu Mitsuyoshi's delightfully sampled songs while playing or in the shower? The vibrant colors, chunky but endearing texturing, and elegant shapes on-screen mesh so well with all the cheesy, life-affirming music and rumbling in your ears. Compared to the diminishing returns of today's triple-A games, this was and remains a paradigm shift in what I'd consider top-end, the confluence of price and immersion.

SEGA's had a hard time keeping this monumental game in circulation over the years, sadly. That license ain't cheap, and neither is porting the game to newer systems. I'm glad the PS3/X360 remaster could happen, even if it's unavailable to buy today. (Beats me why they haven't put the non-licensed Sega Racing Classic version up on storefronts; at least the 360 version is BC ready.) AM2's port team did as excellent a job as they could under what I'd speculate was a limited time & budget. Image quality's crisp, controls map naturally to dual-analog gamepads, and they managed to slot some useful bonus modes in for content-needy home players like myself.

Karaoke mode explains itself: you simply play through a race like normal, but trading out Mitsuyoshi vocals for on-screen lyrics. I know what mode I'm using when the gang and I load this up in VC. Then there's Challenge mode, which introduces new players to concepts like racing lines and shift drifting. I loved going through these even as an experience player; their brief nature lends well to retries. Sure, I'd have loved to race on entirely new tracks made in the original's style, but I also know how previous versions sporting those made compromises in playability or performance. That seems to be a curse for the more content-rich SEGA racers, something Namco avoided for much longer. Still, there's much to enjoy here beyond the arcade mode.

Playing Daytona today should be a lot easier than it is. I hope SEGA sees the adoration this game's had over the past decade. Any chance of them relicensing the HD release for recent platforms, or just porting Sega Racing Classic to avoid the fees, would be awesome. Until then, sailing the blue seas under blue skies is always an option. Any local (b)arcade with a twin or eight-player cab is great, too, assuming they've been maintaining it. This game's too important in arcade history to let slip into unavailability!

So what are you waiting for? We should all be rolling under blue blue skies, playing fun soundbites on the name entry table, and nailing those U-turns around tough corners. Just don't go and lose your sponsors!

1974

Maybe you've seen the term "TTL" thrown about before, mainly for foundational 1970s arcade games. These pre-integrated circuit boards imposed many limits on creators, from Al Alcorn's team making Pong in '72 to SEGA sending the format off with their impressive racer Monaco GP. But in the years before large-scale ICs became feasible for mass-produced games, why not just stack a bunch of transistors next to each other for old times' sake?

Clean Sweep isn't much of a game beyond its historic significance. The idea of single-player Pong, without a computer to play against, must have seemed absurd back then. Of coursed, the solution was simple: fill the screen with other balls to collect. You work to deprive the play area of its starting flourish, bringing back Pong's negative space as you go. Now the opponent is yourself, both an enabler of on-screen events and the disabler should you fail to reflect projectiles. This makes for a fun experience at first, at least until repetition & self-consciousness set in.

So here's the question: why exactly did this disappear into the annals of '70s game lore while Breakout, its clear descendant, ascended to the pantheon? There's many good answers. Atari had production & distribution leverage outmatching even mighty Ramtek, best known then for their Baseball game. Woz & Jobs' design simply had better physics and kinaesthetics, from the tetchy ball-paddle inertia to the simple pleasures of trapping a ball above the wall, watching it go to work. Most likely, the '76 game just had better timing. Pong clone frenzy was the order of the day in Clean Sweep's time, with Atari's own new products struggling to keep up. Something with more of an identity like Ramtek Baseball would have done better than another space game, or what seemed to the public like a weirder take on solo Pong.

(I find it funny how the other review currently claims Clean Sweep is the clone despite predating Breakout. One could boil either game down to "single-player Pong clone" if they really try. That's a kind of reductive take I try to avoid when possible, even when discussing something this rudimentary.)

If you're intrigued by any of this, download DICE and find a copy of Clean Sweep & other TTL games (like the original Breakout, of course!). I can't think of any arcades that might still own, operate, & maintain this relic today other than Galloping Ghost up near Chicago, sadly. And it's nowhere on modern retro collections for obvious emulation-related reasons. But it paved the way for one of the most significant '70s games, and isn't half-bad to play for a few minutes either.

Clean Sweep isn't much of a game beyond its historic significance. The idea of single-player Pong, without a computer to play against, must have seemed absurd back then. Of coursed, the solution was simple: fill the screen with other balls to collect. You work to deprive the play area of its starting flourish, bringing back Pong's negative space as you go. Now the opponent is yourself, both an enabler of on-screen events and the disabler should you fail to reflect projectiles. This makes for a fun experience at first, at least until repetition & self-consciousness set in.

So here's the question: why exactly did this disappear into the annals of '70s game lore while Breakout, its clear descendant, ascended to the pantheon? There's many good answers. Atari had production & distribution leverage outmatching even mighty Ramtek, best known then for their Baseball game. Woz & Jobs' design simply had better physics and kinaesthetics, from the tetchy ball-paddle inertia to the simple pleasures of trapping a ball above the wall, watching it go to work. Most likely, the '76 game just had better timing. Pong clone frenzy was the order of the day in Clean Sweep's time, with Atari's own new products struggling to keep up. Something with more of an identity like Ramtek Baseball would have done better than another space game, or what seemed to the public like a weirder take on solo Pong.

(I find it funny how the other review currently claims Clean Sweep is the clone despite predating Breakout. One could boil either game down to "single-player Pong clone" if they really try. That's a kind of reductive take I try to avoid when possible, even when discussing something this rudimentary.)

If you're intrigued by any of this, download DICE and find a copy of Clean Sweep & other TTL games (like the original Breakout, of course!). I can't think of any arcades that might still own, operate, & maintain this relic today other than Galloping Ghost up near Chicago, sadly. And it's nowhere on modern retro collections for obvious emulation-related reasons. But it paved the way for one of the most significant '70s games, and isn't half-bad to play for a few minutes either.

1991

Remember when games started with saucy sorceresses blasting both of your pauldron-wearing badasses down into the cursed underworld? Pepperidge Farm remembers.

Nihon Falcom already had a history of making some of the best dungeon-crawling odysseys a Japanese PC player could buy. Brandish kept that legacy relevant, and then some. Modern players can laugh at the snappy, initially jarring over-the-shoulder camera, or wonder where the hell they're going in the game's early labyrinths. But I love how this game rewards an unction of patience, a mentality of adapt or die befitting the premise. What would you do if you were Ares Toraernos, decorated mercenary now marooned in the depths of a fallen kingdom? How would you worm your way out of this hell, beleaguered by monsters, deathtraps, and mysteries on all sides? We peer down into this man's trials by fire, yet are thrown to and thro as he methodically rounds corners into one gauntlet after another. To say nothing of his unwanted nemesis Dela Delon, the aforementioned magical minimally clothed madame hunting you down! This wouldn't be the last time Ares—and you, his far-off companion—has to face the bowels of madness and come out intact.

Speaking of jarring, that camera. It's definitely something you can get used to, unless it gives you genuine motion sickness. (Dramamine works for that…unless you're allergic, in which case I understand.) Swapping between mouse and keyboard controls, something new for a Falcom title of this vintage, also asks for some dexterity. But I don't consider this the kind of filter that you can find in more demanding ARPGs like Sekiro or Ninja Gaiden Black. Getting to grips with Brandish asks for a mix of tenacity, analysis, and maybe a few false starts. It's a breezy play, coming in around 8 to 12 hours, give or take. Replays are even encouraged by the game's own ending sequence, which summarizes your playtime and related stats before awarding a ranking. This system would later pop up in Falcom's own Xanadu Next, a boon sign if any.

Should you try Brandish out for size and the split-second camera snaps throws you off, don't panic! Getting used to it took me some time, and yet it paid off so well. I almost want to pity folks like SNESDrunk who, having played the SNES conversion, wrote this game off entirely because of this aspect. Keep an eye on the map and your compass to reorient when needed—even better if the version you're playing has both on-screen at all times.

I'll let you in on a secret: you should be playing the PC-98 version. Or the PSP remake, if experiencing the minimal albeit charming story matters to you. Yes, only the SNES port was ever localized, but I'd take the PC original over it any day. The awkwardness of the console version stems mainly from its reduced HUD and lack of mouse controls. Brandish's lead developers, first Yoshio Kiya (of Xanadu fame) and then Yukio Takahashi, wanted to move Falcom's game designs beyond simple keyboard or joystick schemes. While both Dinosaur and Popful Mail started off Falcom's 1990s stretch with PC-88 era controls, Brandish & its cousin Lord Monarch would explicitly target mouse users, keeping keyboard as an alternative. I tend to use both options, with keys for strafing and mouse to switch between interactions.

Brandish has you crawling through several multi-floor dungeons, each increasingly challenging and claustrophobic through a variety of means. Like the older, arguably more brutal CRPGs Kiya & co. had made, you have limited resources to work with, from deteriorating weapons to a set number of loot chests per level. One thing you'll always have is a chance to rest—if you aren't maybe fatally interrupted, that is. Resting works here much like in classic Rogue-likes, with harsh consequences should a monster attack you as you sleep. But it's your main way to recover health & mana, and an incentive to learn each part of every dungeon. Finding one-way tunnels with doors is a blessing, and managing your limited-space inventory comes naturally. I think Brandish often feels harder than it is; being able to rest & save progress anywhere plays into this. We're years ahead of actually brutal classics like 1985's Xanadu, or even something contemporary like SEGA's Fatal Labyrinth.

Character advancement is also just as interesting here as in Kiya's earlier works. You have to balance between growing physical and magical strength, as well as health, via how you fight enemies. It's very elegant: striking and killing with weapons raises the former, and doing it with spell scrolls helps the latter. This maps almost dead-on to Xanadu's physical-magical dichotomy, just without that game's emphasis on leveling individual weapon experience. Here you can easily switch between armaments, choosing which mix of speed, power, and animation frames works best. Fire and cure spells come quickly, too, enriching your action economy as early as the Vittorian Ruins. By the time I get to truly challenging areas like the Dark Zone, I've maxed out my stats and can only hope to find better gear for my travails. This brings in a bit of that Ys I feeling, where you know only your skills and wisdom can get you through this struggle, not just grinding.

Wisdom is something the people who built these tunnels clearly lacked. The old king of Vittoria, having plunged him and his people into this condemned netherland, had done a fine job setting up spiky pits, poisonous wells, mechanical log rams…the works! Much of Brandish's joy comes from solving all these navigation micro-puzzles while keeping distance from wandering foes. It's hard to fall out of the game's quick "one more floor!" flow. You're never truly alone, either. Shopkeepers occasionally pop up throughout most dungeons, offering both supplies and musings on their lives and the surrounding lore. A certain woman warlock loves to show up and taunt you, only to get bamboozled by the same hazards you've faced (or are about to!). It may be a crunchy 1990 action-RPG with all the aged aspects that entails, but I'd never accuse Brandish of being lifeless. The sequels would only improve in this sense, adding more and more NPCs and story without ever sacrificing that essential oppressive atmosphere and isolation.

Nothing's quite as gratifying as reaching the king's Fortress, packing more heat than a whole army of knights, fearing not so much the bestiary as you do the conundrums. Why is everything so damn fleshy here? How are these pillars moving around the room in such a bizarre way? Will I have to tango with invisible enemies again, or golems awakening around me as I open a suspicious chest? And where am I going anyway?! Brandish avoids the potential worsts of these questions by equipping you with one of gaming history's best mapping systems. Predating the likes of Etrian Odyssey by more than a decade, the game's minimap demonstrates why this game would always have a tough time converting to console play. This precise mouse-based minimap, with multiple swatches you can use to mark map items & boundaries, is itself quite fun to tinker with. Later games would challenge your map-making skills further, going as far as adding enemies that passively destroy your map over time and space! That's not an issue in this first game, thankfully. Falcom's maybe a bit too nice in that regard.

For that matter, I can't shake the feeling that Falcom, still reeling from their turn-of-the-'90s staff exodus (to new studios like Ancient and Quintet), held back on Brandish's ambitions. Popful Mail shares something of a similar fate: these are two wonderfully made adventures, no doubt, but also compromise in key areas. For the former, difficulty balance and repetition can set in later on. For Ares' first expedition into darkness, it's more so the developer's restraint in making truly complex dungeons. I just wish the complexity of both puzzles and combat areas ramped up quicker here, something the rest of the series fixes. Sure, a lot of folks might get stumped at the3 and 5 floor tiles puzzle in Tower, but there's maybe a couple headscratchers here at best. Likewise, combat's sometimes trivialized by the ease of jumping over and away from foes, many of which lack ranged attacks. I can forgive all of this since the rest is just so good, but the creative compromises I've noticed on replays mean I can't really rate this higher. (Brandish 2, incidentally, gets an extra half star for its ambitions despite introducing some more jank of its own.)

Kudos to the boss designs though, especially later on. I'm especially fond of the Black Widow, Lobster, and final boss fights for how they make use your available space to the maximum. Yes, you fight a gigantic lobster towards the end. Brandish sort of gets the Giant Enemy Crab stamp of approval.

All that said, the original Brandish was as awesome & appropriate a successor to Xanadu's legacy as Falcom fans could have hoped for. Hell, it even reminds me of the best parts from Sorcerian and Drasle Family (aka Legacy of the Wizard). Rare is it that an ARPG this old still feels relevant to modern play-styles, from Souls-style character building to the simple but effective itch.io puzzlers made today. It's telling how only Falcom could effectively bring this series to consoles, despite Koei arguably having more resources at the time for their SNES ports. Kiya, Takahashi, and others soon working on this series would iterate on the rock-solid foundation set here. The real downer is how quickly folks turn away from the series itself because it's either funnier or more convenient to crap on the third-first-person perspective. Few ARPG-dungeon crawler hybrids are as consistent, engrossing, and replayable as this.

The studio's largely moved on to more profitable pastures, with Ys and Trails being such huge tentpole series sucking up their time and resources. My kingdom for even a simple port of Brandish: The Dark Revenant to modern platforms! And my heart to those who give this series a chance.

Nihon Falcom already had a history of making some of the best dungeon-crawling odysseys a Japanese PC player could buy. Brandish kept that legacy relevant, and then some. Modern players can laugh at the snappy, initially jarring over-the-shoulder camera, or wonder where the hell they're going in the game's early labyrinths. But I love how this game rewards an unction of patience, a mentality of adapt or die befitting the premise. What would you do if you were Ares Toraernos, decorated mercenary now marooned in the depths of a fallen kingdom? How would you worm your way out of this hell, beleaguered by monsters, deathtraps, and mysteries on all sides? We peer down into this man's trials by fire, yet are thrown to and thro as he methodically rounds corners into one gauntlet after another. To say nothing of his unwanted nemesis Dela Delon, the aforementioned magical minimally clothed madame hunting you down! This wouldn't be the last time Ares—and you, his far-off companion—has to face the bowels of madness and come out intact.

Speaking of jarring, that camera. It's definitely something you can get used to, unless it gives you genuine motion sickness. (Dramamine works for that…unless you're allergic, in which case I understand.) Swapping between mouse and keyboard controls, something new for a Falcom title of this vintage, also asks for some dexterity. But I don't consider this the kind of filter that you can find in more demanding ARPGs like Sekiro or Ninja Gaiden Black. Getting to grips with Brandish asks for a mix of tenacity, analysis, and maybe a few false starts. It's a breezy play, coming in around 8 to 12 hours, give or take. Replays are even encouraged by the game's own ending sequence, which summarizes your playtime and related stats before awarding a ranking. This system would later pop up in Falcom's own Xanadu Next, a boon sign if any.

Should you try Brandish out for size and the split-second camera snaps throws you off, don't panic! Getting used to it took me some time, and yet it paid off so well. I almost want to pity folks like SNESDrunk who, having played the SNES conversion, wrote this game off entirely because of this aspect. Keep an eye on the map and your compass to reorient when needed—even better if the version you're playing has both on-screen at all times.

I'll let you in on a secret: you should be playing the PC-98 version. Or the PSP remake, if experiencing the minimal albeit charming story matters to you. Yes, only the SNES port was ever localized, but I'd take the PC original over it any day. The awkwardness of the console version stems mainly from its reduced HUD and lack of mouse controls. Brandish's lead developers, first Yoshio Kiya (of Xanadu fame) and then Yukio Takahashi, wanted to move Falcom's game designs beyond simple keyboard or joystick schemes. While both Dinosaur and Popful Mail started off Falcom's 1990s stretch with PC-88 era controls, Brandish & its cousin Lord Monarch would explicitly target mouse users, keeping keyboard as an alternative. I tend to use both options, with keys for strafing and mouse to switch between interactions.

Brandish has you crawling through several multi-floor dungeons, each increasingly challenging and claustrophobic through a variety of means. Like the older, arguably more brutal CRPGs Kiya & co. had made, you have limited resources to work with, from deteriorating weapons to a set number of loot chests per level. One thing you'll always have is a chance to rest—if you aren't maybe fatally interrupted, that is. Resting works here much like in classic Rogue-likes, with harsh consequences should a monster attack you as you sleep. But it's your main way to recover health & mana, and an incentive to learn each part of every dungeon. Finding one-way tunnels with doors is a blessing, and managing your limited-space inventory comes naturally. I think Brandish often feels harder than it is; being able to rest & save progress anywhere plays into this. We're years ahead of actually brutal classics like 1985's Xanadu, or even something contemporary like SEGA's Fatal Labyrinth.

Character advancement is also just as interesting here as in Kiya's earlier works. You have to balance between growing physical and magical strength, as well as health, via how you fight enemies. It's very elegant: striking and killing with weapons raises the former, and doing it with spell scrolls helps the latter. This maps almost dead-on to Xanadu's physical-magical dichotomy, just without that game's emphasis on leveling individual weapon experience. Here you can easily switch between armaments, choosing which mix of speed, power, and animation frames works best. Fire and cure spells come quickly, too, enriching your action economy as early as the Vittorian Ruins. By the time I get to truly challenging areas like the Dark Zone, I've maxed out my stats and can only hope to find better gear for my travails. This brings in a bit of that Ys I feeling, where you know only your skills and wisdom can get you through this struggle, not just grinding.

Wisdom is something the people who built these tunnels clearly lacked. The old king of Vittoria, having plunged him and his people into this condemned netherland, had done a fine job setting up spiky pits, poisonous wells, mechanical log rams…the works! Much of Brandish's joy comes from solving all these navigation micro-puzzles while keeping distance from wandering foes. It's hard to fall out of the game's quick "one more floor!" flow. You're never truly alone, either. Shopkeepers occasionally pop up throughout most dungeons, offering both supplies and musings on their lives and the surrounding lore. A certain woman warlock loves to show up and taunt you, only to get bamboozled by the same hazards you've faced (or are about to!). It may be a crunchy 1990 action-RPG with all the aged aspects that entails, but I'd never accuse Brandish of being lifeless. The sequels would only improve in this sense, adding more and more NPCs and story without ever sacrificing that essential oppressive atmosphere and isolation.

Nothing's quite as gratifying as reaching the king's Fortress, packing more heat than a whole army of knights, fearing not so much the bestiary as you do the conundrums. Why is everything so damn fleshy here? How are these pillars moving around the room in such a bizarre way? Will I have to tango with invisible enemies again, or golems awakening around me as I open a suspicious chest? And where am I going anyway?! Brandish avoids the potential worsts of these questions by equipping you with one of gaming history's best mapping systems. Predating the likes of Etrian Odyssey by more than a decade, the game's minimap demonstrates why this game would always have a tough time converting to console play. This precise mouse-based minimap, with multiple swatches you can use to mark map items & boundaries, is itself quite fun to tinker with. Later games would challenge your map-making skills further, going as far as adding enemies that passively destroy your map over time and space! That's not an issue in this first game, thankfully. Falcom's maybe a bit too nice in that regard.

For that matter, I can't shake the feeling that Falcom, still reeling from their turn-of-the-'90s staff exodus (to new studios like Ancient and Quintet), held back on Brandish's ambitions. Popful Mail shares something of a similar fate: these are two wonderfully made adventures, no doubt, but also compromise in key areas. For the former, difficulty balance and repetition can set in later on. For Ares' first expedition into darkness, it's more so the developer's restraint in making truly complex dungeons. I just wish the complexity of both puzzles and combat areas ramped up quicker here, something the rest of the series fixes. Sure, a lot of folks might get stumped at the

Kudos to the boss designs though, especially later on. I'm especially fond of the Black Widow, Lobster, and final boss fights for how they make use your available space to the maximum. Yes, you fight a gigantic lobster towards the end. Brandish sort of gets the Giant Enemy Crab stamp of approval.

All that said, the original Brandish was as awesome & appropriate a successor to Xanadu's legacy as Falcom fans could have hoped for. Hell, it even reminds me of the best parts from Sorcerian and Drasle Family (aka Legacy of the Wizard). Rare is it that an ARPG this old still feels relevant to modern play-styles, from Souls-style character building to the simple but effective itch.io puzzlers made today. It's telling how only Falcom could effectively bring this series to consoles, despite Koei arguably having more resources at the time for their SNES ports. Kiya, Takahashi, and others soon working on this series would iterate on the rock-solid foundation set here. The real downer is how quickly folks turn away from the series itself because it's either funnier or more convenient to crap on the third-first-person perspective. Few ARPG-dungeon crawler hybrids are as consistent, engrossing, and replayable as this.

The studio's largely moved on to more profitable pastures, with Ys and Trails being such huge tentpole series sucking up their time and resources. My kingdom for even a simple port of Brandish: The Dark Revenant to modern platforms! And my heart to those who give this series a chance.

Cold take, but Infogrames really was poison for just about every company & brand it amoeba-ed. Ocean, GT Interactive, Humungous Entertainment...even old ailing Atari (properties, not its people) via the Hasbro Entertainment buyout. All got wrapped up into a top-heavy, mismanaged juggernaut that eventually fell to pieces, only rebuilding well into their Atari SA rebrand.

Atari Anniversary Edition isn't too interesting on its own. The 12 games included were harder to access back then, sure, but the DIY arcade revival & emulation scenes have obviated the issue. (Hence why Atari 50 is so commendable, going well beyond just the usual roster by adding "what if"-style games and supplements galore.) Emulation quality's alright, and it certainly seems playable on every platform it reached. I can think of worse compilations to spend an evening with.

What strikes me, though, is the "anniversary" bit. Anniversary of what, exactly? Centipede? Tempest? Asteroids Deluxe? Those three share equal billing with the other nine, though. Infogrames' idea of matching a lightweight arcade compilation with this much pomp and circumstance is hilarious. No doubt the team at Digital Eclipse liked the paycheck, but who did they think the rainbow armadillo was fooling? My dad, I suppose. It's the one Dreamcast game he played much, and thankfully our local barcade can slake that thirst.

It's a shame that Digital Eclipse didn't get more of a chance to do here what they can now. I suppose that's just corporate reality and the publisher shooting for a quick buck, value be damned. Even DE's earlier PS1 Atari collection had a bonus documentary unlike this. Dark days. All this makes it easier to appreciate the old game compilations we get today, inching closer and closer to the style of box-set release you get from Criterion, Arrow, and other boutique film shops. Let's hope things continue to improve—that curated redistribution of notable classics can further unshackle from the fetters of simple nostalgia.

Atari Anniversary Edition isn't too interesting on its own. The 12 games included were harder to access back then, sure, but the DIY arcade revival & emulation scenes have obviated the issue. (Hence why Atari 50 is so commendable, going well beyond just the usual roster by adding "what if"-style games and supplements galore.) Emulation quality's alright, and it certainly seems playable on every platform it reached. I can think of worse compilations to spend an evening with.

What strikes me, though, is the "anniversary" bit. Anniversary of what, exactly? Centipede? Tempest? Asteroids Deluxe? Those three share equal billing with the other nine, though. Infogrames' idea of matching a lightweight arcade compilation with this much pomp and circumstance is hilarious. No doubt the team at Digital Eclipse liked the paycheck, but who did they think the rainbow armadillo was fooling? My dad, I suppose. It's the one Dreamcast game he played much, and thankfully our local barcade can slake that thirst.

It's a shame that Digital Eclipse didn't get more of a chance to do here what they can now. I suppose that's just corporate reality and the publisher shooting for a quick buck, value be damned. Even DE's earlier PS1 Atari collection had a bonus documentary unlike this. Dark days. All this makes it easier to appreciate the old game compilations we get today, inching closer and closer to the style of box-set release you get from Criterion, Arrow, and other boutique film shops. Let's hope things continue to improve—that curated redistribution of notable classics can further unshackle from the fetters of simple nostalgia.

1993

It's no Shitty Shitty Bang Bang, but I'd prefer it be a well-designed puzzler than a mere funny PC-98 meme. Sex 2 ahem

Bit^2's 1993 train-crash avoidance simulator starts you off with an egghead of a railway operator asking you to manually operate their trains. Why? All the company's sensors & computers have gone haywire, and only you have the skills to run it all until it's fixed! Simple enough, just give me the master control panel and—oh, wait, I have to flip every little switch. Every train's gotta pick up their passengers or cargo, then make it safely to the exit. Someone's gonna owe me money after this job.

Chitty Chitty Train leaves you plenty compensated, thankfully. The game's mouse controls are smooth yet precise. Its audiovisuals are rock solid, from jaunty chiptune marches to the intricate pixel art. (Seriously, why doesn't this title get more attention from PC-X8 art rebloggers and art bots?! The eroge picks are getting old, fellas.) And just like you'd expect from a meticulous PC puzzler from this era a la Lemmings, each level offers plenty of challenge. Well-designed challenges, might I add.

We're far from Transport Tycoon and its descendants here, with nary an automatic timetable at hand. Think of it more like an arcade-y, non-sim distillation of A-Train's transit mechanics. All your train scheduling happens through manually clicking on switches, calculating how long different types of cars will travel the circuit you put them on. Quite a few early puzzles give you very limited headroom, stacking multiple moving engines across shared track they'll easily bash heads on. Planning your moves and switch timing is the meta, but a good amount of improvisation can help when least expected. It hardly feels like a train version of Sokoban, where you're so obviously restricted and can only realistically solve the puzzle in a given way.

Best of all, there's a map maker! Creating and sharing your levels via the game disk might have mattered more back in its heyday, but Chitty Chitty Train's such a small game in size that it's trivial now. You can try it out today via PC-98 emulators (hint: check a certain Archive), and I think any fans of old-school logic games will get plenty out of this very overlooked romp. Although the game's always had English menus, the recent fan patch does translate the opening if you're interested.

Bit^2's 1993 train-crash avoidance simulator starts you off with an egghead of a railway operator asking you to manually operate their trains. Why? All the company's sensors & computers have gone haywire, and only you have the skills to run it all until it's fixed! Simple enough, just give me the master control panel and—oh, wait, I have to flip every little switch. Every train's gotta pick up their passengers or cargo, then make it safely to the exit. Someone's gonna owe me money after this job.

Chitty Chitty Train leaves you plenty compensated, thankfully. The game's mouse controls are smooth yet precise. Its audiovisuals are rock solid, from jaunty chiptune marches to the intricate pixel art. (Seriously, why doesn't this title get more attention from PC-X8 art rebloggers and art bots?! The eroge picks are getting old, fellas.) And just like you'd expect from a meticulous PC puzzler from this era a la Lemmings, each level offers plenty of challenge. Well-designed challenges, might I add.

We're far from Transport Tycoon and its descendants here, with nary an automatic timetable at hand. Think of it more like an arcade-y, non-sim distillation of A-Train's transit mechanics. All your train scheduling happens through manually clicking on switches, calculating how long different types of cars will travel the circuit you put them on. Quite a few early puzzles give you very limited headroom, stacking multiple moving engines across shared track they'll easily bash heads on. Planning your moves and switch timing is the meta, but a good amount of improvisation can help when least expected. It hardly feels like a train version of Sokoban, where you're so obviously restricted and can only realistically solve the puzzle in a given way.

Best of all, there's a map maker! Creating and sharing your levels via the game disk might have mattered more back in its heyday, but Chitty Chitty Train's such a small game in size that it's trivial now. You can try it out today via PC-98 emulators (hint: check a certain Archive), and I think any fans of old-school logic games will get plenty out of this very overlooked romp. Although the game's always had English menus, the recent fan patch does translate the opening if you're interested.

2011

More like a last resort, but hey, gotta use those air miles.

Wuhu Island seems like a downgrade from the charcuterie board that is Pilotwings 64's islands. You're forever going to squint into the twilight while riding thermals, or futzing around behind the volcano in a jetpack thinking "I could be in Little States right now, sneaking into airplane garages for shits 'n' giggles." Thankfully there's still a rock-solid game here, building off PW64's knack for mission design and controls.

Pretty much every vehicle feels as good here, if not better, from the training plane to the pedal glider. (I'm a big fan of the latter, a beefed-up hang glider with more room for error and skillful control). Knocking out the early challenges to organically unlock the second-tier ride types is as fun as you'd hope for. And to their credit, Monster Games understands how to subtly haul you around the island between missions, switching up the scale & sightlines of your aerial trip with ease.

I still think the minigames, fun as they are, aren't anywhere near good as the original game's attack 'copter mission, nor the cannon & hopper you could abuse in PW64. The squirrel suit seems very underutilized for all you could do with it; no "dive through portals!" mission sticks in my mind. And the free-flight mode takes one step forward with collecting the hints, but a gorillion steps back via that time limit. Did they just not understand the appeal of traveling the world in PW64's Birdman suit, or were they just too self-conscious about only having one island to work with?

Except they have the golf island, which also goes relatively ignored aside from the fight against Meca Hawk. Bringing that big 'ol box of bolts back was awesome and hilarious (a set of missions involving it would have been even better). Truth be told, it's only the clever reuse of such limited content in Pilotwings Resort that earns it that last half-star. I love the polished game loop, replaying missions for better ranks, etc. But you'd think Nintendo would have afforded Monster Games a few more months to add more, at least in terms of modes, mission variations, and an unlockable Birdman.

As the last Pilotwings we might ever see, given the corp's disinterest in the franchise, it's a nice stopping point for sure. I'm perhaps a bit biased as this was my early-adopted 3DS exclusive of choice, but it's very much worth a visit to Wuhu on these wings of music if you get the chance. (Or, you know, cross the high seas to reach the island.) At least you'll have some outright jammin' funk & fusion hitting your ears, and an excellent implementation of 3D back when it seemed like just a novelty.

Anyway, either I'm going to end up finding some new indie take on the Pilotwings concept or it's high time someone like me makes a fully-fledged revival of it.

Wuhu Island seems like a downgrade from the charcuterie board that is Pilotwings 64's islands. You're forever going to squint into the twilight while riding thermals, or futzing around behind the volcano in a jetpack thinking "I could be in Little States right now, sneaking into airplane garages for shits 'n' giggles." Thankfully there's still a rock-solid game here, building off PW64's knack for mission design and controls.

Pretty much every vehicle feels as good here, if not better, from the training plane to the pedal glider. (I'm a big fan of the latter, a beefed-up hang glider with more room for error and skillful control). Knocking out the early challenges to organically unlock the second-tier ride types is as fun as you'd hope for. And to their credit, Monster Games understands how to subtly haul you around the island between missions, switching up the scale & sightlines of your aerial trip with ease.

I still think the minigames, fun as they are, aren't anywhere near good as the original game's attack 'copter mission, nor the cannon & hopper you could abuse in PW64. The squirrel suit seems very underutilized for all you could do with it; no "dive through portals!" mission sticks in my mind. And the free-flight mode takes one step forward with collecting the hints, but a gorillion steps back via that time limit. Did they just not understand the appeal of traveling the world in PW64's Birdman suit, or were they just too self-conscious about only having one island to work with?

Except they have the golf island, which also goes relatively ignored aside from the fight against Meca Hawk. Bringing that big 'ol box of bolts back was awesome and hilarious (a set of missions involving it would have been even better). Truth be told, it's only the clever reuse of such limited content in Pilotwings Resort that earns it that last half-star. I love the polished game loop, replaying missions for better ranks, etc. But you'd think Nintendo would have afforded Monster Games a few more months to add more, at least in terms of modes, mission variations, and an unlockable Birdman.

As the last Pilotwings we might ever see, given the corp's disinterest in the franchise, it's a nice stopping point for sure. I'm perhaps a bit biased as this was my early-adopted 3DS exclusive of choice, but it's very much worth a visit to Wuhu on these wings of music if you get the chance. (Or, you know, cross the high seas to reach the island.) At least you'll have some outright jammin' funk & fusion hitting your ears, and an excellent implementation of 3D back when it seemed like just a novelty.

Anyway, either I'm going to end up finding some new indie take on the Pilotwings concept or it's high time someone like me makes a fully-fledged revival of it.

1979

As said by a wise old sage: "be rootin', be tootin', and by Kong be shootin'...but most of all, be kind."

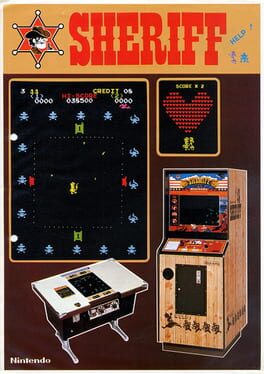

Everyone remembered the OK Corral differently. The Earps and feuding families each had their self-serving accounts of the shootout. John Ford, Stuart Lake, and other myth-makers turned the participants into legends, models of masculinity, freedom-seekers, and a long-lost Old West But the truth's rarely so glamorous or controversial. Just as the OK Corral gunfight never took place in the corral itself, Nintendo's Sheriff was never just the handiwork of a newly-hired Shigeru Miyamoto. How vexing it is that the echoes of Western mythologizing reach this far!

I am exaggerating a bit with regards to how Nintendo fans & gamers at large view this game. Miyamoto's almost always discussed in relation to Sheriff as an artist & assistant designer, not the producer (that'll be Genyo Takeda, later of StarTropics fame). That's not to diminish what the famous creator did contribute. While Nintendo largely put out clones and what I'd charitably call "experiments" by this point, their '79 twin-stick shooter defies that trend. It's still a bit rough-hewn, like any old cowboy, yet very fun and replayable.

Compared to earlier efforts like Western Gun & Boot Hill, there's more creative bending of Wild West stereotypes here, to mixed results. Though not the first major arcade game with an intermission, the scenes here are cute, a sign that the Not Yet Very Big N's developers were quick to match their competition. I do take umbrage with translating Space Invaders' aliens to bandits, though. Sure, this long predates modern discussions about negative stereotyping in games media, but that hardly disqualifies it. Let's just say that this game's rather unkind to its characters, from the doofy-looking lawman to his blatant damsel-in-distress & beyond. Respect to the condor, though. That's some gumption, flying above the fray on this baleful night, just askin' fer a plummet.

The brilliant part here is giving you solid twin-stick controls for moving & shooting well ahead of Midway's Robotron 2084. The dim bit is those enemy bullets, slow as molasses and firing only in cardinal directions. Normally you or the operator could just flip a DIP switch to raise the difficulty, but those options are absent too. What results is a fun, but relatively easy take on the Invaders template, one which rewards you a bit too much prior to developing the skills encouraged in Taito's originals. For example, it's much easier to aggressively fire here than to take cover, given the easily ignorable shields & posts. Your dexterity here compared to Space Invaders, or even Galaxian, tends to outweigh your opponents, for better and worse.

A counter-example comes when a few bandits charge into the corral, able to lunge at you if you trot too close. This spike in danger is exciting, an alternative to Galaxian's waves system which similarly revolutionizes your play-space. Where once you could just snipe at leisure, now you have to keep distance or get stabbed in the back! Of course, ranged exchanges were all that happened at the OK Corral. A little artistic liberty playing up the tropes can work out after all. Perhaps our strapping Roy Rogers believes in good 'ol fashioned marksmanship; he's a fool to deny himself fisticuffs, but a brave one.

When I'm not gunning down the circle of knives or playing matador with them, I think about how simple but compelling the game's premise is. We've gone from one Wild West tropset (the Mexican standoffs seen in Gunman & its ilk) to another, more politically charged one. You may be a lone marshall, but not much more than a deputized gang shooter. The game inadvertently conveys a message of liquid morality & primacy of who's more immediately anthropomorphic—empowering the Stetson hat over the sombrero. All basic American History 101 stuff, but displayed this vividly, this blatantly in a game this early? This seems less so Miyamoto's charm, more so his accidental wit.

Life's just too easy for the Wyatt Earps of this fictionalized, simplistic world. Another round in the corral, another kiss in the saloon, rinse and repeat. Maybe I'm giving too much credit to a one-and-done go at complexifying the paradigm Taito started, but it's filling food for thought. I highly recommend at least trying Sheriff today just to experience its odd thrills & ersatz yet perceptive view of the corral shootout tradition. The Fords & Miyamotos of the world, working with film & video games in their infancy, had a knack for making the most of limited possibilities. For all my misgivings, the distorted tales of the Old West are ample fodder for a destructive ride on the joysticks. Sheriff's team would go on to make works as iconic as Donkey Kong, so why downplay their earliest attempts to work with material as iconic as this?

I'm sure Sheriff will came back 'round these parts, like a tumbleweed hops from Hollywood ghost towns to the raster screen. Don't lemme see ya causin' trouble in The Old MAME, son.

Everyone remembered the OK Corral differently. The Earps and feuding families each had their self-serving accounts of the shootout. John Ford, Stuart Lake, and other myth-makers turned the participants into legends, models of masculinity, freedom-seekers, and a long-lost Old West But the truth's rarely so glamorous or controversial. Just as the OK Corral gunfight never took place in the corral itself, Nintendo's Sheriff was never just the handiwork of a newly-hired Shigeru Miyamoto. How vexing it is that the echoes of Western mythologizing reach this far!

I am exaggerating a bit with regards to how Nintendo fans & gamers at large view this game. Miyamoto's almost always discussed in relation to Sheriff as an artist & assistant designer, not the producer (that'll be Genyo Takeda, later of StarTropics fame). That's not to diminish what the famous creator did contribute. While Nintendo largely put out clones and what I'd charitably call "experiments" by this point, their '79 twin-stick shooter defies that trend. It's still a bit rough-hewn, like any old cowboy, yet very fun and replayable.

Compared to earlier efforts like Western Gun & Boot Hill, there's more creative bending of Wild West stereotypes here, to mixed results. Though not the first major arcade game with an intermission, the scenes here are cute, a sign that the Not Yet Very Big N's developers were quick to match their competition. I do take umbrage with translating Space Invaders' aliens to bandits, though. Sure, this long predates modern discussions about negative stereotyping in games media, but that hardly disqualifies it. Let's just say that this game's rather unkind to its characters, from the doofy-looking lawman to his blatant damsel-in-distress & beyond. Respect to the condor, though. That's some gumption, flying above the fray on this baleful night, just askin' fer a plummet.

The brilliant part here is giving you solid twin-stick controls for moving & shooting well ahead of Midway's Robotron 2084. The dim bit is those enemy bullets, slow as molasses and firing only in cardinal directions. Normally you or the operator could just flip a DIP switch to raise the difficulty, but those options are absent too. What results is a fun, but relatively easy take on the Invaders template, one which rewards you a bit too much prior to developing the skills encouraged in Taito's originals. For example, it's much easier to aggressively fire here than to take cover, given the easily ignorable shields & posts. Your dexterity here compared to Space Invaders, or even Galaxian, tends to outweigh your opponents, for better and worse.

A counter-example comes when a few bandits charge into the corral, able to lunge at you if you trot too close. This spike in danger is exciting, an alternative to Galaxian's waves system which similarly revolutionizes your play-space. Where once you could just snipe at leisure, now you have to keep distance or get stabbed in the back! Of course, ranged exchanges were all that happened at the OK Corral. A little artistic liberty playing up the tropes can work out after all. Perhaps our strapping Roy Rogers believes in good 'ol fashioned marksmanship; he's a fool to deny himself fisticuffs, but a brave one.

When I'm not gunning down the circle of knives or playing matador with them, I think about how simple but compelling the game's premise is. We've gone from one Wild West tropset (the Mexican standoffs seen in Gunman & its ilk) to another, more politically charged one. You may be a lone marshall, but not much more than a deputized gang shooter. The game inadvertently conveys a message of liquid morality & primacy of who's more immediately anthropomorphic—empowering the Stetson hat over the sombrero. All basic American History 101 stuff, but displayed this vividly, this blatantly in a game this early? This seems less so Miyamoto's charm, more so his accidental wit.

Life's just too easy for the Wyatt Earps of this fictionalized, simplistic world. Another round in the corral, another kiss in the saloon, rinse and repeat. Maybe I'm giving too much credit to a one-and-done go at complexifying the paradigm Taito started, but it's filling food for thought. I highly recommend at least trying Sheriff today just to experience its odd thrills & ersatz yet perceptive view of the corral shootout tradition. The Fords & Miyamotos of the world, working with film & video games in their infancy, had a knack for making the most of limited possibilities. For all my misgivings, the distorted tales of the Old West are ample fodder for a destructive ride on the joysticks. Sheriff's team would go on to make works as iconic as Donkey Kong, so why downplay their earliest attempts to work with material as iconic as this?

I'm sure Sheriff will came back 'round these parts, like a tumbleweed hops from Hollywood ghost towns to the raster screen. Don't lemme see ya causin' trouble in The Old MAME, son.

1978

And we can try, to understand,

The Atari games' effect on Nam[co]

Whether you're a plumber or a cute dungeon crawler, you're indebted to Nam, you're indebted to Nam. But it's not alright—it's not even okay. And I can't look the other way. Toru Iwatani's first game shows all the growing pains & missteps you'd expect from an arcade developer dabbling in microchip games after years of electromechanical (eremeka) products. It's more than a curio, though. The beginnings of Pac-Man's cheeky fun show up even this early, if you can believe it. Just know it's not the real deal—the Hee Bee Gee Bees, if you will.

Speaking later in his career, an Iwatani then swamped with management duties asserted that "making video games is an act of kindness to others, a tangible gift of happiness." This axiom of purpose comes after his own complaints about the stagnation of '80s game centers, then flush with shoot-em-ups and less-than-innovative software. Around 1987, even Namco's own arcade output had trailed off in mechanical ambition, trading out the derring-do of Dragon Buster for the excellent but conventional Dragon Spirit. One could argue he had rose-tinted glasses this early, ignoring all the clones and production frenzy of Golden Age arcade games like his own. But he's arguing most for elegance and player-first design, something attempted with Gee Bee.

Conceived as a compromise between the pinball tables he wanted to make and Pres. Nakamura & co.'s interest in imports like Breakout, their 1978 debut had ambitions. It's an early go at combining multiple mechanics and score strategies found in Steve Wozniak's creation and post-war pinball designs. Anyone walking by the cab would see the vague, amusing outline of a human face made from barriers & breakables. Together with the requisite comical marquee & paddle, this would have seemed familiar enough to players at the time while enticing them with novelty. What's the bee chipping away at? Are we stinging our selves with delight as the blocks dissipate, our attacks moving faster and faster? That kind of imagination springs forth from even a premise as simple as this.

I'm sad to say that the mind-meld of pinball and electronic squash just wasn't feasible this early on. Gee Bee offers neither the flash and nuances of the best flipper games Chicago could offer, nor the pure and addictive game loop Wozniak wrought from Clean Sweep. Iwatani and his co-developers hamstrung themselves by refusing to commit one way or the other. There's a few too many ways to screw yourself over in Gee Bee, from less intuitive physics to the screen resetting every time you lose a ball. Inability to reach high scores is one thing, but that denial of progress is a buzzkill. All your careful threading of the needle to hit all the NAMCO letters for the multiplier can go to waste in an instant. All the patience needed to clear one upper half, thus blocking the ball from a previously open tunnel, feels like a cruel joke.

If what I'm saying gives you the heebie-jeebies, then don't overthink it. The game's recognizable to modern players, and fun for a little bit at least. But there's just no longevity here except for ardent score seekers. I can see why, for all of Namco's work to promote it, Gee Bee didn't take off at home or abroad. Space Invaders had innovated upon the destructive form of Pong that Breakout started, while this feels like an evolutionary dead-end. Bomb Bee & Cutie Q would try to salvage this with some success, of course. I'm just unsurprised that Iwatani learned from the mistakes made here, keeping that focus on levity & eclectic design in Pac-Man & Libble Rabble. On a technical level, this board still has some positives of note, mainly its fluidity & amount of color vs. the rest of the market. It's worth a try for historic value, and a sneak peek of the game development ethos Iwatani spread to other Namco notables in the coming years.

The Atari games' effect on Nam[co]

Whether you're a plumber or a cute dungeon crawler, you're indebted to Nam, you're indebted to Nam. But it's not alright—it's not even okay. And I can't look the other way. Toru Iwatani's first game shows all the growing pains & missteps you'd expect from an arcade developer dabbling in microchip games after years of electromechanical (eremeka) products. It's more than a curio, though. The beginnings of Pac-Man's cheeky fun show up even this early, if you can believe it. Just know it's not the real deal—the Hee Bee Gee Bees, if you will.

Speaking later in his career, an Iwatani then swamped with management duties asserted that "making video games is an act of kindness to others, a tangible gift of happiness." This axiom of purpose comes after his own complaints about the stagnation of '80s game centers, then flush with shoot-em-ups and less-than-innovative software. Around 1987, even Namco's own arcade output had trailed off in mechanical ambition, trading out the derring-do of Dragon Buster for the excellent but conventional Dragon Spirit. One could argue he had rose-tinted glasses this early, ignoring all the clones and production frenzy of Golden Age arcade games like his own. But he's arguing most for elegance and player-first design, something attempted with Gee Bee.

Conceived as a compromise between the pinball tables he wanted to make and Pres. Nakamura & co.'s interest in imports like Breakout, their 1978 debut had ambitions. It's an early go at combining multiple mechanics and score strategies found in Steve Wozniak's creation and post-war pinball designs. Anyone walking by the cab would see the vague, amusing outline of a human face made from barriers & breakables. Together with the requisite comical marquee & paddle, this would have seemed familiar enough to players at the time while enticing them with novelty. What's the bee chipping away at? Are we stinging our selves with delight as the blocks dissipate, our attacks moving faster and faster? That kind of imagination springs forth from even a premise as simple as this.

I'm sad to say that the mind-meld of pinball and electronic squash just wasn't feasible this early on. Gee Bee offers neither the flash and nuances of the best flipper games Chicago could offer, nor the pure and addictive game loop Wozniak wrought from Clean Sweep. Iwatani and his co-developers hamstrung themselves by refusing to commit one way or the other. There's a few too many ways to screw yourself over in Gee Bee, from less intuitive physics to the screen resetting every time you lose a ball. Inability to reach high scores is one thing, but that denial of progress is a buzzkill. All your careful threading of the needle to hit all the NAMCO letters for the multiplier can go to waste in an instant. All the patience needed to clear one upper half, thus blocking the ball from a previously open tunnel, feels like a cruel joke.

If what I'm saying gives you the heebie-jeebies, then don't overthink it. The game's recognizable to modern players, and fun for a little bit at least. But there's just no longevity here except for ardent score seekers. I can see why, for all of Namco's work to promote it, Gee Bee didn't take off at home or abroad. Space Invaders had innovated upon the destructive form of Pong that Breakout started, while this feels like an evolutionary dead-end. Bomb Bee & Cutie Q would try to salvage this with some success, of course. I'm just unsurprised that Iwatani learned from the mistakes made here, keeping that focus on levity & eclectic design in Pac-Man & Libble Rabble. On a technical level, this board still has some positives of note, mainly its fluidity & amount of color vs. the rest of the market. It's worth a try for historic value, and a sneak peek of the game development ethos Iwatani spread to other Namco notables in the coming years.

2000

You know not a lick of FOMO until you peer into the Library of Babel that is original The Sims modding homepages. I ended up spending so much time modding this game that I realized I'd be better off messing around with the official expansions instead. And then I remembered that The Sims 2 effectively carries over all the original game's charm, and then some. Then again, I think the Second Life community inherited more of the "casual fever dream" creative aspirations that had been possessing social games like this since the days of MUDs (let alone worlds.com).

As something I played all the way back in kindergarten, not understanding an iota of the classic Maxis humor & sim details, The Sims has maintained its mystique well into modern day. From impromptu fires to questionable adulting skills, there's just a lot to take in whenever you start playing a new family. I learned how to play rotationally here before moving on to the sequels, knowing those would be even more intimidating. Consider this the training grounds for getting the most out of the series proper, perhaps.

One thing The Sims 2, 3, and definitely 4 are lacking in is Jerry Martin. His iteration on the long-form improvisations of virtuosos like Keith Jarrett & George Winston always puts a smile on my face, even knowing how simple, even workmanlike the chord cycles are. And the eclectic mix of big band, latin, & fusion jazz elsewhere sets this well apart from the more hyperactive, genre-agnostic work Mark Mothersbaugh excels at in the sequels. All in all, the audio direction is so damn focused.

Even if you skip this for more moddable, sophisticated series entries, it's both a fun nostalgia trip & one of the not-so-secretly best sim game soundtracks ever. The Sims remains very accessible today thanks to new installers & quality-of-life mods, plus a clean user interface enabling you in all the key areas. This was the Little Computer People of the Internet, even more than early MMOs like Ultima Online hinted at. A timeline w/o Maxis' quintessential suburban simulator would look unrecognizable, and I'm not sure I'd want it any other way.

As something I played all the way back in kindergarten, not understanding an iota of the classic Maxis humor & sim details, The Sims has maintained its mystique well into modern day. From impromptu fires to questionable adulting skills, there's just a lot to take in whenever you start playing a new family. I learned how to play rotationally here before moving on to the sequels, knowing those would be even more intimidating. Consider this the training grounds for getting the most out of the series proper, perhaps.

One thing The Sims 2, 3, and definitely 4 are lacking in is Jerry Martin. His iteration on the long-form improvisations of virtuosos like Keith Jarrett & George Winston always puts a smile on my face, even knowing how simple, even workmanlike the chord cycles are. And the eclectic mix of big band, latin, & fusion jazz elsewhere sets this well apart from the more hyperactive, genre-agnostic work Mark Mothersbaugh excels at in the sequels. All in all, the audio direction is so damn focused.

Even if you skip this for more moddable, sophisticated series entries, it's both a fun nostalgia trip & one of the not-so-secretly best sim game soundtracks ever. The Sims remains very accessible today thanks to new installers & quality-of-life mods, plus a clean user interface enabling you in all the key areas. This was the Little Computer People of the Internet, even more than early MMOs like Ultima Online hinted at. A timeline w/o Maxis' quintessential suburban simulator would look unrecognizable, and I'm not sure I'd want it any other way.

1983

Green the putt. Ball the club. Falcom the Nihon. Meme the name.

Before Nintendo & HAL Laboratory codified the bare basics of home golf games—graphical aiming, multi-step power bar, you know the drill—experiments like this obscure Falcom release were the norm. They weren't alone: everyone from Atari to T&E Soft tried their hand at making either casual putt romps or hardcore simulations. Both consoles & micro-computers of the era were hard-pressed to make golf feel fun, even if they could simplify or complexify it. As a regular cassette game coded in BASIC, Computer the Golf always had humble aims, uninterested in changing trends.

I still managed to have a good time despite the archaic mechanics & presentation, however. Each hole's sensibly designed & placed to reflect growing expectations for player skill. Your club variety & multi-step power bar (yes, these existed before Nintendo's Golf!) also make precision shots easier to achieve. For 3500 yen, players would have gotten decent value, especially if you wanted something from Falcom with more of a puzzle feel. There's also the requisite scorecard feature, plus cursor key controls at a time when most PC-88 & FM-7 releases stuck with numpad keys.