BjgBug

9 reviews liked by BjgBug

Gimmick: Exact Mix

2020

Virtua Hamster

TBD

I had a blast playing through Tengo Project's Ninja Saviors. I ran through the game mostly as Ninja, a hulking cyborg-ninja with glowing red eyes and huge metal arms. It felt like I was playing through one of those ultraviolent 90s OVAs, and I was playing as the bad guy. Like all beat em ups, there's not very much difficulty here outside of the bosses, and even the majority of those are chumps; unlike most beat em ups, the minute to minute gameplay is really fun and interesting. The different action buttons all change depending on the direction you're holding, and the context—whether you're holding an enemy, on the ground, in the air, dashing, etc. There's a ton of depth to the beating them upping, and getting a handle on your character is really rewarding. My only real complaint is that a few bosses can feel cheap, and that it's just a smidge too long for me to run through on a whim. Looking forward to dipping back into this one and playing with the other characters.

Air Twister

2022

'As from the darkening gloom a silver dove upsoars, so fled thy soul into the realms above, regions of peace and everlasting love.'

– John Keats, As from the darkening gloom a silver dove, 1814.

Within two years, Steven Meretsky had established a solid reputation with his work on Planetfall (1983), Sorcerer (1984) and The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1984). In 1984, Ronald Reagan's re-election against Walter Mondale was a historic landslide, with Mondale only managing to win Minnesota and Washington, D.C. This resounding victory was due to the favourable economic climate, as the recession had eased in 1983. At the same time, commentators pointed to the inadequacy of Mondale's campaign compared to Reagan's: while Mondale's policies were very liberal by the standards of the US political landscape, they were seen as inimical to the interests of the middle class, who were more aligned with Reagan's agenda. Ultimately, Mondale's defeat was a setback for the progressive ideas fermenting on college campuses and elsewhere. A poll by the College Voice of Connecticut College, released on 6 November 1984, showed a significant preference for Mondale among students (51% to Reagan's 37%). But more interestingly, when asked 'Which candidate better reflects your views on the following issues?', Mondale emerged as the clear preference on all social issues (Equal Rights Amendment: 76/16; Abortion: 82/15; Social spending: 72/22; Nuclear freeze: 64/28) – on economic issues (47/46), his honesty undoubtedly worked against him. [1]

The Reagan presidency: a political critique

Reagan's landslide re-election was therefore a bitter disappointment for progressives. For Meretsky, making a political game as a way of taking a stand became a necessity. In contrast to the humorous style of his previous titles, A Mind Forever Voyaging was intended to be a serious piece of fiction, on a par with the classics of science fiction. Meretsky clearly incorporated the legacy of the classic counter-utopias: the characteristic themes of Yevgeny Zamyatin's My (1920-1921), Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932) and George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), with their depiction of totalitarian states imposing tight control over their populations, are particularly evident. Just as Zamyatin described his disillusionment with the October Revolution (1917) and Huxley explored the socio-economic crisis following the 1929 Crash, Meretsky anchors his work in a critique of the key policies of the Reagan presidency. A Mind Forever Voyaging should therefore be read as a continuation of this critical tradition in science fiction.

The player assumes the role of PRISM, an artificial intelligence that has reached the singularity in 2031. The game manual begins with a short story that introduces the genesis of the PRISM project, which lived in a simulation to gain consciousness and emotions. In Perry Simm's fake life, the computer knew his parents, fell in love and married a woman called Jill. One day, Perelman, the head of the PRISM project, informs the AI that it was all a simulation and that he needs its help to evaluate the effects of Senator Richard Ryder's proposed Plan for Renewed National Purpose. The player, in the life of Perry Simm, can then explore the United States of 2041, ten years after the implementation of the Plan, to measure the changes in society. The game is not about solving puzzles, but about recording events and discussions and passing them on to Perelman's team. In the first act, the populist, war-mongering, neo-liberal rationale of the Plan seems to be followed by positive effects and economic recovery, just like the Reagan Doctrine. The streets are full of life and the population is generally happy. The cinemas offer a wide range of films, including a Korean production, Freefall. Cultural life is vibrant through a network of museums, concert halls, galleries and libraries.

From political commentary to interactive fiction: exploration and immersion

However, the player who embraces the non-linearity and freedom of exploration can already see the latent signs of economic inequality. While the city centre is welcoming and vibrant, the industrial area to the east is in a more dilapidated state, highlighting the lack of public support for this less privileged population and the superficial development projects that mask the structural problems. In some respects, the geography of the city is reminiscent of Chicago, and the problems of racial segregation, which will be exacerbated later in the simulation, are already apparent. The Border Security Force, already created in 2031 and anticipating the creation of Homeland Security (2002), also gives a glimpse of the armed force of the executive, ready to defend its interests and its conception of society. In any case, Perelman is satisfied with the results of the 2041 simulation, but he still has some concerns and asks PRISM to continue to study the simulation in depth to ensure that the Plan does not have any negative consequences. A dive into 2051 gives way to a very different picture of American society.

It has become largely radicalised, and from the very first moments the player witnesses scenes of police brutality, even in the protagonist's own apartment. As Perry moves from one street to the next, he is stopped by violent incidents and observes the deterioration of the socio-economic context: freedom of the press has been largely curtailed by the government, while religious proselytism has reached a critical point, with the success of a new religious sect taking precedence over traditional Protestantism and Catholicism. Cultural life is in decline, while environmental problems are on the rise, with mentions of over-exploitation and acid rain – classic environmentalist tropes of the 1980s. Perhaps most striking are the scenes of family life. The player can interact with Jill and observe how changes in society affect domestic harmony. This approach predates the main idea of Norman Spinrad's novel Russian Spring (1991), which also uses family relationships to explore the socio-political context of an alternate world in which the Soviets have emerged victorious from the Cold War. In A Mind Forever Voyaging, when the BSF invade the family home, the political changes take on a much more personal tone for PRISM, and Meretsky uses the power of interactive fiction to convey these emotions to the player, in contrast to the generally neutral and cold descriptions of totalitarian violence outside the protagonist's home.

A defence of a liberal and patriotic America

Subsequent simulations show a dramatic worsening of the situation: the family unit is completely disrupted, while public executions, concentration camps and the return of slavery, driven by the Church of God's Word, increase. Meretsky's critique is not subtle, but he contrasts this dystopian world with his own patriotic vision of a liberal United States. He attaches great importance to the democratic republicanism of the US, as evidenced by the negative valence given to the dismantling of statues of former presidents. His approach to food is also positivistic and carnist. When the player visits Burgerworld – the new name of Burger Meister –, meat has been replaced by algae and soy alternatives, which are portrayed as abhorrent.

Insofar as Meretsky's positions are in opposition to the Reagan presidency, A Mind Forever Voyaging is not intended to be a resolutely radical pamphlet either: it borrows many themes from contemporary social movements without indulging in the political activism of the 1960s Black Panthers or the Berkeley campus, which in fact culminated in the deadly confrontation at People's Park (1969) during Reagan's governorship. The symbolic power of the game lies in its less subtle elements. As the simulation progresses, the likelihood of the player dying for various reasons increases, a situation that culminates in the final section of the second act, where every action seems to be fatal for Perry. Armed with all these experiences, PRISM and Perelman must take action to prevent the Plan from being adopted, despite Ryder's threats. This last passage is the only puzzle in the title that requires the player to consult the documentation in PRISM's library. The player is then treated to a touching epilogue, which I must admit is one of my favourite moments in any video game.

A Mind Forever Voyaging is therefore not outstanding for its puzzles, but for its scale for its time. At the end of the era of text-based games, it offers a dense, exploration-oriented experience, with scenes in every corner of the city. In the first act, Perelman provides a list of events to record, but this disappears in the second act, where the player is free to explore and record whatever they wish. There is a real curiosity in comparing the simulations to see how the situation deteriorates over the decades. Perry is a witness in this cruel universe, where he has no control over his surroundings; when his family life collapses, he can only console Jill until it no longer works. At most, a command line 'RECORD ON' gives hope that these snapshots will allow Perelman to use his full weight to stop the Plan. A Mind Forever Voyaging is a unique work from the 1980s and retains its critical charge at a time of global far right resurgence. Just as it is always enlightening to revisit classic science fiction literature alongside more recent releases, so it is ever appropriate to reexamine A Mind Forever Voyaging.

__________

[1] Connecticut College, College Voice, 6th November, 1984, p. 1.

– John Keats, As from the darkening gloom a silver dove, 1814.

Within two years, Steven Meretsky had established a solid reputation with his work on Planetfall (1983), Sorcerer (1984) and The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1984). In 1984, Ronald Reagan's re-election against Walter Mondale was a historic landslide, with Mondale only managing to win Minnesota and Washington, D.C. This resounding victory was due to the favourable economic climate, as the recession had eased in 1983. At the same time, commentators pointed to the inadequacy of Mondale's campaign compared to Reagan's: while Mondale's policies were very liberal by the standards of the US political landscape, they were seen as inimical to the interests of the middle class, who were more aligned with Reagan's agenda. Ultimately, Mondale's defeat was a setback for the progressive ideas fermenting on college campuses and elsewhere. A poll by the College Voice of Connecticut College, released on 6 November 1984, showed a significant preference for Mondale among students (51% to Reagan's 37%). But more interestingly, when asked 'Which candidate better reflects your views on the following issues?', Mondale emerged as the clear preference on all social issues (Equal Rights Amendment: 76/16; Abortion: 82/15; Social spending: 72/22; Nuclear freeze: 64/28) – on economic issues (47/46), his honesty undoubtedly worked against him. [1]

The Reagan presidency: a political critique

Reagan's landslide re-election was therefore a bitter disappointment for progressives. For Meretsky, making a political game as a way of taking a stand became a necessity. In contrast to the humorous style of his previous titles, A Mind Forever Voyaging was intended to be a serious piece of fiction, on a par with the classics of science fiction. Meretsky clearly incorporated the legacy of the classic counter-utopias: the characteristic themes of Yevgeny Zamyatin's My (1920-1921), Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932) and George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), with their depiction of totalitarian states imposing tight control over their populations, are particularly evident. Just as Zamyatin described his disillusionment with the October Revolution (1917) and Huxley explored the socio-economic crisis following the 1929 Crash, Meretsky anchors his work in a critique of the key policies of the Reagan presidency. A Mind Forever Voyaging should therefore be read as a continuation of this critical tradition in science fiction.

The player assumes the role of PRISM, an artificial intelligence that has reached the singularity in 2031. The game manual begins with a short story that introduces the genesis of the PRISM project, which lived in a simulation to gain consciousness and emotions. In Perry Simm's fake life, the computer knew his parents, fell in love and married a woman called Jill. One day, Perelman, the head of the PRISM project, informs the AI that it was all a simulation and that he needs its help to evaluate the effects of Senator Richard Ryder's proposed Plan for Renewed National Purpose. The player, in the life of Perry Simm, can then explore the United States of 2041, ten years after the implementation of the Plan, to measure the changes in society. The game is not about solving puzzles, but about recording events and discussions and passing them on to Perelman's team. In the first act, the populist, war-mongering, neo-liberal rationale of the Plan seems to be followed by positive effects and economic recovery, just like the Reagan Doctrine. The streets are full of life and the population is generally happy. The cinemas offer a wide range of films, including a Korean production, Freefall. Cultural life is vibrant through a network of museums, concert halls, galleries and libraries.

From political commentary to interactive fiction: exploration and immersion

However, the player who embraces the non-linearity and freedom of exploration can already see the latent signs of economic inequality. While the city centre is welcoming and vibrant, the industrial area to the east is in a more dilapidated state, highlighting the lack of public support for this less privileged population and the superficial development projects that mask the structural problems. In some respects, the geography of the city is reminiscent of Chicago, and the problems of racial segregation, which will be exacerbated later in the simulation, are already apparent. The Border Security Force, already created in 2031 and anticipating the creation of Homeland Security (2002), also gives a glimpse of the armed force of the executive, ready to defend its interests and its conception of society. In any case, Perelman is satisfied with the results of the 2041 simulation, but he still has some concerns and asks PRISM to continue to study the simulation in depth to ensure that the Plan does not have any negative consequences. A dive into 2051 gives way to a very different picture of American society.

It has become largely radicalised, and from the very first moments the player witnesses scenes of police brutality, even in the protagonist's own apartment. As Perry moves from one street to the next, he is stopped by violent incidents and observes the deterioration of the socio-economic context: freedom of the press has been largely curtailed by the government, while religious proselytism has reached a critical point, with the success of a new religious sect taking precedence over traditional Protestantism and Catholicism. Cultural life is in decline, while environmental problems are on the rise, with mentions of over-exploitation and acid rain – classic environmentalist tropes of the 1980s. Perhaps most striking are the scenes of family life. The player can interact with Jill and observe how changes in society affect domestic harmony. This approach predates the main idea of Norman Spinrad's novel Russian Spring (1991), which also uses family relationships to explore the socio-political context of an alternate world in which the Soviets have emerged victorious from the Cold War. In A Mind Forever Voyaging, when the BSF invade the family home, the political changes take on a much more personal tone for PRISM, and Meretsky uses the power of interactive fiction to convey these emotions to the player, in contrast to the generally neutral and cold descriptions of totalitarian violence outside the protagonist's home.

A defence of a liberal and patriotic America

Subsequent simulations show a dramatic worsening of the situation: the family unit is completely disrupted, while public executions, concentration camps and the return of slavery, driven by the Church of God's Word, increase. Meretsky's critique is not subtle, but he contrasts this dystopian world with his own patriotic vision of a liberal United States. He attaches great importance to the democratic republicanism of the US, as evidenced by the negative valence given to the dismantling of statues of former presidents. His approach to food is also positivistic and carnist. When the player visits Burgerworld – the new name of Burger Meister –, meat has been replaced by algae and soy alternatives, which are portrayed as abhorrent.

Insofar as Meretsky's positions are in opposition to the Reagan presidency, A Mind Forever Voyaging is not intended to be a resolutely radical pamphlet either: it borrows many themes from contemporary social movements without indulging in the political activism of the 1960s Black Panthers or the Berkeley campus, which in fact culminated in the deadly confrontation at People's Park (1969) during Reagan's governorship. The symbolic power of the game lies in its less subtle elements. As the simulation progresses, the likelihood of the player dying for various reasons increases, a situation that culminates in the final section of the second act, where every action seems to be fatal for Perry. Armed with all these experiences, PRISM and Perelman must take action to prevent the Plan from being adopted, despite Ryder's threats. This last passage is the only puzzle in the title that requires the player to consult the documentation in PRISM's library. The player is then treated to a touching epilogue, which I must admit is one of my favourite moments in any video game.

A Mind Forever Voyaging is therefore not outstanding for its puzzles, but for its scale for its time. At the end of the era of text-based games, it offers a dense, exploration-oriented experience, with scenes in every corner of the city. In the first act, Perelman provides a list of events to record, but this disappears in the second act, where the player is free to explore and record whatever they wish. There is a real curiosity in comparing the simulations to see how the situation deteriorates over the decades. Perry is a witness in this cruel universe, where he has no control over his surroundings; when his family life collapses, he can only console Jill until it no longer works. At most, a command line 'RECORD ON' gives hope that these snapshots will allow Perelman to use his full weight to stop the Plan. A Mind Forever Voyaging is a unique work from the 1980s and retains its critical charge at a time of global far right resurgence. Just as it is always enlightening to revisit classic science fiction literature alongside more recent releases, so it is ever appropriate to reexamine A Mind Forever Voyaging.

__________

[1] Connecticut College, College Voice, 6th November, 1984, p. 1.

Power Shovel

1999

'I work and

work, yet my life gets no easier

I stare at my hands.'

– Takuboku Ishikawa (1886-1912).

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (6th Jun. – 12th Jun., 2023).

In the post-war years, the myth of work as a vehicle for social success was shaped by Japan's exceptional economic recovery. Getting a job came with the promise that it would last a lifetime, without the worker having to endure another job search. The construction of this social myth was intensified from the autumn of 1960, when Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda unveiled his Income Doubling Plan (Shotoku Baizō Keikaku), which aimed to stimulate the economy through a spectrum of liberal and social measures. The plan was largely successful, with Japan's GDP growing at double-digit rates: by diverting public attention from foreign affairs to economic issues, Ikeda had succeeded in grounding confidence in the government in GDP performance. This very favourable situation enabled Japan to gain a high international standing and stabilise its domestic situation. The downside of such a system, however, is that it is particularly susceptible to losing the support of the general public should the economic situation swing the other way.

The freeter and the myth of self-discovery

The collapse of the economic bubble in the 1990s led to a reconfiguration of the labour market. Unemployment soared, and companies could no longer sustain the myth of a permanent career: in effect, they sought to retain their best and brightest while relying on a young, unskilled workforce to serve as temporary expedients. These part-timers are known as freeters, and they are the subject of a rather subtle definition in Japanese capitalist theory: on the one hand, they are presented as individuals marginalised by the labour market, but on the other, part-time work is described as an opportunity to discover more personal passions and to refocus on something other than the professional world. In other words, part-time work frees people from the constraints and boredom of a lifelong career. This ideological illusion enabled the Japanese government and corporations to justify their harsh socio-economic policies with the support of the cultural production of the time.

The drama Shomuni (1998), adapted from the manga of the same name, was a big surprise for Japanese television, dominating the ratings in a very unexpected way. The drama focuses on the female employees of the Shomu ni division of the Manpan Corporation. The least efficient women are sent to this department to do the most menial tasks, as the company hopes that they will leave on their own to avoid paying financial compensation. Unfortunately, the women of Shomu ni are content with their positions and use their free time to indulge their passions. Unconsciously, Shomuni presents unskilled work as a vector of emancipation for those who are able to take advantage of the opportunities it offers.

Gamifying labour: capitalism's hidden prison

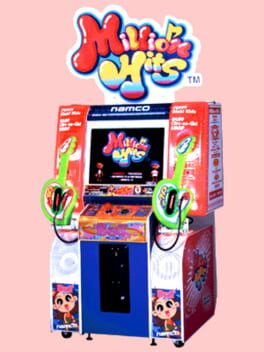

Beyond dramas that 'focused on cool young people imbued with a sense of freedom and personal agency searching for happiness' [1], video games also play a role in shaping this idealised image of low-skilled work. While Shenmue (1999) highlighted the mind-numbing repetitiveness of work, Power Shovel glamorises the construction industry. The player is given control of a power shovel to perform decontextualised tasks such as moving sand, digging holes or demolishing buildings. The task is not an easy one, as the controls are rather unintuitive and the timers extremely tight. The player is urged by the angry voice of the taskmaster to learn the controls as quickly as possible. The goal is not so much to have a detailed understanding of the various manoeuvres, but rather to memorise fixed sequences so as to repeat the same movements as quickly as possible without having to think. The game's tutorial fully embraces this alienation, as the player is invited to follow a shadow worker whose inputs are slowly and mindlessly displayed on the screen.

There is something terribly oppressive about Power Shovel, which manages to reproduce the alienation of manual labour while wrapping it in a modern fantasy. In the arcade mode, the most tasteless tasks are interspersed with more playful challenges, such as serving soup with the shovel, catching turtles, or reducing a luxury car to rubble. These cathartic challenges help to make the job fun, with the protagonist's paycheck treated as a scorecard. The yelling of the taskmaster, even if it carries the weight of hierarchical domination, is rather amusing in the context of the game. Power Shovel oozes ideological cynicism, and the title never really hides from it. While the tone mimics that of a Japanese game show – Ichirō Nagai's voice lends itself well to this – the game proudly displays the colours of the Komatsu company, which distributed many copies of the game to its employees.

Job insecurity and the fiction of happiness

The player gradually finds their bearings and adapts to the rigid controls. Unsurprisingly, the first-person view allows for much better control of the machine, and is undoubtedly the best perspective for working efficiently and beating the most difficult timers, thus fully assimilating the player to the worker. The 'Licence King' mode, which tests the player's skills, feels like a compulsory passage. The reward is, ominously, the promise of a job, which only adds to the capitalist malice. The bright colours and the Taito mascot are further subterfuges that mask the harshness of the workplace behind the prospect of amusement, as long as one is willing to put in the effort to succeed. The same themes can be found in the drama Furītā, ie o kau (2010), in which a young man, disillusioned with the traditional office job, turns to part-time work in order to break free from social expectations – namely to get married, start a family and become a homeowner. He also finds love while working in the construction industry.

Christopher Perkins argued that the success of Furītā, ie o kau was indicative of a new shift in the representation of the freeter in the late 2000s. He wrote: 'rather than illuminating and exploring a number of important social and economic challenges currently facing Japanese society, the series is content to tell a story of personal development that falls into sentimentality: maintaining the image of family as the locus of welfare provision and rendering risk a moral challenge to be overcome by resilient individuals, rather than a complex of structural challenges to be addressed by the state' [2]. Power Shovel was already a manifestation of this reality. The title is quite enjoyable to play once the initial difficulty barrier has been overcome. But therein lies its problem. Despite the game's promises, the player never becomes the 'King of Komatsu'. Instead, they always play the role of a slave worker being berated by the taskmaster: that is the secret magic of capitalism.

__________

[1] Christopher Perkins, 'Part-timer, buy a house. Middle-class precarity, sentimentality and learning the meaning of work', in Kristina Iwata-Weickgenannt, Roman Rosenbaum (ed.), Visions of Precarity in Japanese Popular Culture and Literature, Routledge, London, 2015, p. 69.

[2] Ibid., p. 80.

work, yet my life gets no easier

I stare at my hands.'

– Takuboku Ishikawa (1886-1912).

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (6th Jun. – 12th Jun., 2023).

In the post-war years, the myth of work as a vehicle for social success was shaped by Japan's exceptional economic recovery. Getting a job came with the promise that it would last a lifetime, without the worker having to endure another job search. The construction of this social myth was intensified from the autumn of 1960, when Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda unveiled his Income Doubling Plan (Shotoku Baizō Keikaku), which aimed to stimulate the economy through a spectrum of liberal and social measures. The plan was largely successful, with Japan's GDP growing at double-digit rates: by diverting public attention from foreign affairs to economic issues, Ikeda had succeeded in grounding confidence in the government in GDP performance. This very favourable situation enabled Japan to gain a high international standing and stabilise its domestic situation. The downside of such a system, however, is that it is particularly susceptible to losing the support of the general public should the economic situation swing the other way.

The freeter and the myth of self-discovery

The collapse of the economic bubble in the 1990s led to a reconfiguration of the labour market. Unemployment soared, and companies could no longer sustain the myth of a permanent career: in effect, they sought to retain their best and brightest while relying on a young, unskilled workforce to serve as temporary expedients. These part-timers are known as freeters, and they are the subject of a rather subtle definition in Japanese capitalist theory: on the one hand, they are presented as individuals marginalised by the labour market, but on the other, part-time work is described as an opportunity to discover more personal passions and to refocus on something other than the professional world. In other words, part-time work frees people from the constraints and boredom of a lifelong career. This ideological illusion enabled the Japanese government and corporations to justify their harsh socio-economic policies with the support of the cultural production of the time.

The drama Shomuni (1998), adapted from the manga of the same name, was a big surprise for Japanese television, dominating the ratings in a very unexpected way. The drama focuses on the female employees of the Shomu ni division of the Manpan Corporation. The least efficient women are sent to this department to do the most menial tasks, as the company hopes that they will leave on their own to avoid paying financial compensation. Unfortunately, the women of Shomu ni are content with their positions and use their free time to indulge their passions. Unconsciously, Shomuni presents unskilled work as a vector of emancipation for those who are able to take advantage of the opportunities it offers.

Gamifying labour: capitalism's hidden prison

Beyond dramas that 'focused on cool young people imbued with a sense of freedom and personal agency searching for happiness' [1], video games also play a role in shaping this idealised image of low-skilled work. While Shenmue (1999) highlighted the mind-numbing repetitiveness of work, Power Shovel glamorises the construction industry. The player is given control of a power shovel to perform decontextualised tasks such as moving sand, digging holes or demolishing buildings. The task is not an easy one, as the controls are rather unintuitive and the timers extremely tight. The player is urged by the angry voice of the taskmaster to learn the controls as quickly as possible. The goal is not so much to have a detailed understanding of the various manoeuvres, but rather to memorise fixed sequences so as to repeat the same movements as quickly as possible without having to think. The game's tutorial fully embraces this alienation, as the player is invited to follow a shadow worker whose inputs are slowly and mindlessly displayed on the screen.

There is something terribly oppressive about Power Shovel, which manages to reproduce the alienation of manual labour while wrapping it in a modern fantasy. In the arcade mode, the most tasteless tasks are interspersed with more playful challenges, such as serving soup with the shovel, catching turtles, or reducing a luxury car to rubble. These cathartic challenges help to make the job fun, with the protagonist's paycheck treated as a scorecard. The yelling of the taskmaster, even if it carries the weight of hierarchical domination, is rather amusing in the context of the game. Power Shovel oozes ideological cynicism, and the title never really hides from it. While the tone mimics that of a Japanese game show – Ichirō Nagai's voice lends itself well to this – the game proudly displays the colours of the Komatsu company, which distributed many copies of the game to its employees.

Job insecurity and the fiction of happiness

The player gradually finds their bearings and adapts to the rigid controls. Unsurprisingly, the first-person view allows for much better control of the machine, and is undoubtedly the best perspective for working efficiently and beating the most difficult timers, thus fully assimilating the player to the worker. The 'Licence King' mode, which tests the player's skills, feels like a compulsory passage. The reward is, ominously, the promise of a job, which only adds to the capitalist malice. The bright colours and the Taito mascot are further subterfuges that mask the harshness of the workplace behind the prospect of amusement, as long as one is willing to put in the effort to succeed. The same themes can be found in the drama Furītā, ie o kau (2010), in which a young man, disillusioned with the traditional office job, turns to part-time work in order to break free from social expectations – namely to get married, start a family and become a homeowner. He also finds love while working in the construction industry.

Christopher Perkins argued that the success of Furītā, ie o kau was indicative of a new shift in the representation of the freeter in the late 2000s. He wrote: 'rather than illuminating and exploring a number of important social and economic challenges currently facing Japanese society, the series is content to tell a story of personal development that falls into sentimentality: maintaining the image of family as the locus of welfare provision and rendering risk a moral challenge to be overcome by resilient individuals, rather than a complex of structural challenges to be addressed by the state' [2]. Power Shovel was already a manifestation of this reality. The title is quite enjoyable to play once the initial difficulty barrier has been overcome. But therein lies its problem. Despite the game's promises, the player never becomes the 'King of Komatsu'. Instead, they always play the role of a slave worker being berated by the taskmaster: that is the secret magic of capitalism.

__________

[1] Christopher Perkins, 'Part-timer, buy a house. Middle-class precarity, sentimentality and learning the meaning of work', in Kristina Iwata-Weickgenannt, Roman Rosenbaum (ed.), Visions of Precarity in Japanese Popular Culture and Literature, Routledge, London, 2015, p. 69.

[2] Ibid., p. 80.

The Tower of Druaga

1984

Tower of Druaga is probably the first great social game; and like the first week of Pokémon Go, like long offline MMOs, it's impossible to play Druaga the way it was meant to be played: at an arcade with other players, swapping tips, theories, or ideas as to how to get to the next floor in the tower of Druaga. It's no wonder this didn't catch on in the States, where you play arcade games with your friends, if you play them with anyone at all.

As it is today, Tower of Druaga is, genuinely, a fun combat puzzle game. I'm a fan of NES The Legend of Zelda's combat, and that same simple swordplay is here almost verbatim, though there's a little more friction here; the item-based puzzle/combat loop of Zelda clearly starts here (Miyamoto is an outspoken fan of this game). The puzzle solutions are fun to do, even if the solutions themselves are complete insane. To find treasure chests, you will rotate your joystick three times; you will swing your sword from your starting spot, but first you will turn your character so they're not facing the outside wall so when you do you don't also destroy your crucial pickaxe; you will pass through one enemy and then and only then kill three of a different enemy type.

I had a good time playing up the tower, sincerely marveling at its tricks and what it asked of you. Really worth playing for a while to see whats so special about it. Don't even feel bad using a guide. For a game like this, the guide isn't cheating so much as it is an analog to that social experience that's impossible to get today.

As it is today, Tower of Druaga is, genuinely, a fun combat puzzle game. I'm a fan of NES The Legend of Zelda's combat, and that same simple swordplay is here almost verbatim, though there's a little more friction here; the item-based puzzle/combat loop of Zelda clearly starts here (Miyamoto is an outspoken fan of this game). The puzzle solutions are fun to do, even if the solutions themselves are complete insane. To find treasure chests, you will rotate your joystick three times; you will swing your sword from your starting spot, but first you will turn your character so they're not facing the outside wall so when you do you don't also destroy your crucial pickaxe; you will pass through one enemy and then and only then kill three of a different enemy type.

I had a good time playing up the tower, sincerely marveling at its tricks and what it asked of you. Really worth playing for a while to see whats so special about it. Don't even feel bad using a guide. For a game like this, the guide isn't cheating so much as it is an analog to that social experience that's impossible to get today.

5 lists liked by BjgBug

by Bottle |

62 Games

by waverly |

56 Games

by BeeKirby |

36 Games

by BeeKirby |

113 Games

by letshugbro |

22 Games