Um conto violento apresentado de uma forma simples que me tocou muito - eu geralmente valorizo mais a parte do "jogo" nas obras que eu jogo e ainda assim, deparado com um arcade game onde você gerencia múltiplos recursos e aumenta o seu high score, essa foi a parte que mais ficou comigo. Talvez seja por causa do quanto eles se conectam para representar a dor que você causa a si mesmo, o sangue de uma garota que se espreita pelo asilo que a mostrou o inferno, assim como ela voce fica constantemente à beira da morte. É legal perceber o quão bem isso é representado por um jogo tão curto e experimental.

As an arcade game that blends the technical and experiential, Quantum Bummer Blues is at least as great as RayForce 😎

Heather's an absolute genius, combining the dynamic positioning of Libble Rabble and nuanced resource managment of the best Raizing games, all while tackling themes of violence and imprisonment with such purpose and clarity that they're impossible to overlook.

The core mechanics of encircling atoms and dodging turrets are so strong that they don't need stinky 'level design' to stay engaging and the narrative doesn't need explicit characterization to feel emotionally impactful

All in all, this game is a CERTIFIED BANGER

Heather's an absolute genius, combining the dynamic positioning of Libble Rabble and nuanced resource managment of the best Raizing games, all while tackling themes of violence and imprisonment with such purpose and clarity that they're impossible to overlook.

The core mechanics of encircling atoms and dodging turrets are so strong that they don't need stinky 'level design' to stay engaging and the narrative doesn't need explicit characterization to feel emotionally impactful

All in all, this game is a CERTIFIED BANGER

An arcade-style game about violence and death, both of which fuel the entire world. There's always something about to go wrong, whether your blood meter is high or low. You can't do too well, can't stick out too much, or else you'll be dealt with quickly. Can't spend too much time wallowing or hiding, or you'll never make it to the next screen. You need just the right amount of pain, waiting for the right moment to feed yourself, or to hurt yourself intentionally. It's a demanding balancing act, always having to give something up to survive, and it feels like it never gets easier. But maybe getting to the end will prove something, to someone. It could change something, even if it's the smallest change possible, even if it's a change so small that no one even notices. It could.

Video games are so much better than we give them credit for.

Video games are so much better than we give them credit for.

You are blood.

Blood of a young girl murdered within a Quantum Prison for Troubled Youths. Blood oozing through the cracks of the prison to set the others free.

I am not the best at giving very insightful thoughts onto most games, I'm very much a neophyte in that regard but what I can tell you about this game in particular is why I gel with it.

Quantum Bummer Blues is a game very much rooted in the macabre, as much of the writing paints the picture of a very violent and unsettling world that our unnamed female protagonist has had to live with for several years. Lobotomies, begging for release, possibly even being assaulted for her sexuality. This prison is one of both the mind and soul.

Much of the game (as I interpreted it, I believe this game is vague enough to result in many interpretations to its meaning as I imagine that is the intent.) is the dying thoughts of the murdered girl, as we wander through very bizarre visual rooms, some shaped like a husky, others being what appears to be a human heart. All the while having thoughts of parents abandoning her to this place, and wanting to be freed from the torment.

We start in very simple geometric rooms but soon evolve to these more strange and specific designs that very much gives the vibe of life flashing before your eyes. The music as well gives this feeling of nostalgia washing over you but the hum of static and numbers never truly goes away.

If you'll pardon a personal anecdote here, this game reminds me of something that happened to me only a few months ago. I went to get a routine blood test, as you do when you have a family history of diabetes and heart disease.

These always make me nervous you see, because I hate needles and seeing blood leaving my body. As the doctor shoved the needle in I felt an indescribable pain. Soon I noticed my world fading to black, fuzzy like an old black and white film. My ears began to only hear the staticy noises.

I felt the closest to death I had ever been in my entire life within that moment, but I still didn't pass out.

The fear though, the sheer terror of that moment has stuck with me ever since that day, and I believe that same fear can be found within the contents of Quantum Bummer Blues.

The state between living and not living, self harm in order to survive, this game has an approach that I believe most games wish they could attain.

The gameplay itself as someone else has pointed out is very reminiscent of Libble Rabble, and I would find myself having to agree. The game rewards you for circling around the microbes you can absorb for points by letting them grow bigger to absorb them for even more points without raising the amount of blood drain you have.

It asks you at various points to prioritize which resource you will sacrifice in order to survive, self harm being one of the many ways to regain blood in order to progress.

You can even use this risky shot maneuver that will drain a lot of blood fast, but can also help in giving tons of points as well as speeding up the process of making the microbes larger.

It is also very difficult, and I have not beaten it as of this review (I did use the coloring book mode to see how far I got, and I was very close to the end with my last scored playthrough). I think the difficulty is fine, the game asks the player to reevaluate their approach to video games as a give and take system and I can appreciate how it does so.

Edit: I forgot to add in a part, but the amount of cool things that high level players can do is awesome, Heather's High Score Run Video gave me a lot of insight and is how I was able to improve my skills and get as far as I did.

Personal recommendation when you play the game: play on keyboard. I had been playing on Xbox One controls for most of my playthroughs and outside of hurting my thumb, it is not remotely as precise as keyboard controls.

Quantum Bummer Blues is definitely a game I recommend for people who want to see a very intriguing take on the results of violence, law enforcement, among many other things, as well as a unique gameplay style that will test you in ways few other games can. It's definitely MeCore that's for sure, and I'll have to look into Heather's other games in the future.

P.S. Gonna go listen to that Johnny Cash album later, love that guy's music.

Blood of a young girl murdered within a Quantum Prison for Troubled Youths. Blood oozing through the cracks of the prison to set the others free.

I am not the best at giving very insightful thoughts onto most games, I'm very much a neophyte in that regard but what I can tell you about this game in particular is why I gel with it.

Quantum Bummer Blues is a game very much rooted in the macabre, as much of the writing paints the picture of a very violent and unsettling world that our unnamed female protagonist has had to live with for several years. Lobotomies, begging for release, possibly even being assaulted for her sexuality. This prison is one of both the mind and soul.

Much of the game (as I interpreted it, I believe this game is vague enough to result in many interpretations to its meaning as I imagine that is the intent.) is the dying thoughts of the murdered girl, as we wander through very bizarre visual rooms, some shaped like a husky, others being what appears to be a human heart. All the while having thoughts of parents abandoning her to this place, and wanting to be freed from the torment.

We start in very simple geometric rooms but soon evolve to these more strange and specific designs that very much gives the vibe of life flashing before your eyes. The music as well gives this feeling of nostalgia washing over you but the hum of static and numbers never truly goes away.

If you'll pardon a personal anecdote here, this game reminds me of something that happened to me only a few months ago. I went to get a routine blood test, as you do when you have a family history of diabetes and heart disease.

These always make me nervous you see, because I hate needles and seeing blood leaving my body. As the doctor shoved the needle in I felt an indescribable pain. Soon I noticed my world fading to black, fuzzy like an old black and white film. My ears began to only hear the staticy noises.

I felt the closest to death I had ever been in my entire life within that moment, but I still didn't pass out.

The fear though, the sheer terror of that moment has stuck with me ever since that day, and I believe that same fear can be found within the contents of Quantum Bummer Blues.

The state between living and not living, self harm in order to survive, this game has an approach that I believe most games wish they could attain.

The gameplay itself as someone else has pointed out is very reminiscent of Libble Rabble, and I would find myself having to agree. The game rewards you for circling around the microbes you can absorb for points by letting them grow bigger to absorb them for even more points without raising the amount of blood drain you have.

It asks you at various points to prioritize which resource you will sacrifice in order to survive, self harm being one of the many ways to regain blood in order to progress.

You can even use this risky shot maneuver that will drain a lot of blood fast, but can also help in giving tons of points as well as speeding up the process of making the microbes larger.

It is also very difficult, and I have not beaten it as of this review (I did use the coloring book mode to see how far I got, and I was very close to the end with my last scored playthrough). I think the difficulty is fine, the game asks the player to reevaluate their approach to video games as a give and take system and I can appreciate how it does so.

Edit: I forgot to add in a part, but the amount of cool things that high level players can do is awesome, Heather's High Score Run Video gave me a lot of insight and is how I was able to improve my skills and get as far as I did.

Personal recommendation when you play the game: play on keyboard. I had been playing on Xbox One controls for most of my playthroughs and outside of hurting my thumb, it is not remotely as precise as keyboard controls.

Quantum Bummer Blues is definitely a game I recommend for people who want to see a very intriguing take on the results of violence, law enforcement, among many other things, as well as a unique gameplay style that will test you in ways few other games can. It's definitely MeCore that's for sure, and I'll have to look into Heather's other games in the future.

P.S. Gonna go listen to that Johnny Cash album later, love that guy's music.

rage, the blood curling screams across generational continuous visceral warfare to keep lives compounded, perpetual punishment. we slowly bleed out, only when forcibly running into fire do we remember to keep going.

against an increasingly powerful syndicate that cages, twirling the keys in their fingers giggling on "rehabilitation"

the bells toll, jail cells are more than bent metal they can constrain the flesh through words and deeds until freedoms become a beautiful splatter for the boot stamping down on this stupid queer

they'll keep functioning the glorious Machine until we break it

against an increasingly powerful syndicate that cages, twirling the keys in their fingers giggling on "rehabilitation"

the bells toll, jail cells are more than bent metal they can constrain the flesh through words and deeds until freedoms become a beautiful splatter for the boot stamping down on this stupid queer

they'll keep functioning the glorious Machine until we break it

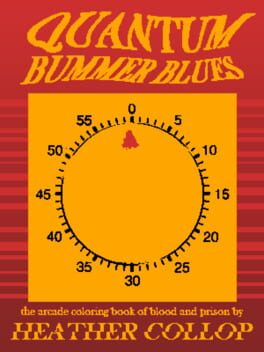

Quantum Bummer Blues é um jogo bastante DENSO. Nele, você toma controle do sangue de uma prisioneira morta, e seu objetivo é escapar pelo ralo de uma prisão. O jogo tem um visual retrô e certamente busca influência de arcades.

Particularmente, eu achei a jogabilidade pouco intuitiva, foi uma experiência muito difícil, mesmo assistindo ao vídeo explicativo da desenvolvedora no Youtube. Após várias tentativas, decidi usar o coloringbook mode, e só assim consegui zerá-lo. Talvez isso tenha ocorrido por conta da minha falta de familiaridade com jogos arcade, talvez não; mas certamente afetou minha experiência, inclusive a de me interessar na história do jogo.

Particularmente, eu achei a jogabilidade pouco intuitiva, foi uma experiência muito difícil, mesmo assistindo ao vídeo explicativo da desenvolvedora no Youtube. Após várias tentativas, decidi usar o coloringbook mode, e só assim consegui zerá-lo. Talvez isso tenha ocorrido por conta da minha falta de familiaridade com jogos arcade, talvez não; mas certamente afetou minha experiência, inclusive a de me interessar na história do jogo.

Sem dúvidas, os impactos de jogar este ainda reverberarão em minha forma de intrepretar e produzir jogos. A estrutura de um antigão dos arcades é reapropriada para criar desconforto - o trilhar de seu sangue é mecanicamente e simbolicamente um ato de flagelação - para contar uma história de violência horripilante: o sangue rasteja por uma mega-estrutura abstrata construída para distorcer o que é inaceitável na polpa em que esta sociedade acredita que ela merece ser. Um ode ao jogo curto que bate pesado.

CW:Text Vomit, Excessive Gamer Tangents, Very Mild gameplay spoilers

Est. Reading length: Inchoately N/A

Policy

-----------------------------------------------------------

I should note I got a free copy of the game from the developer because we are cautious friends. Not only for the sake of 'journalistic integrity' but also to point out that there's never been a situation where I played a game a developer gave me for free who I know personally and then I didn't like the game which is to say, I don't have a litmus test for how easy or hard I am to pay off. Who can say if I would have spoken about this game if I didn't like it? That being said the primary reason it is this way is out of poverty and not because I don't think the game is worth the money or anything like that. I definitely think with the amount of time it'll take to figure it out its totally worth it and one of the best games of the year so far.

Anyway, in respect to what everyone else has already offered on the game, I'll skip all the theming and presentation talk and just talk about the game mechanics proper. To me I feel like there's one hanging rhetorical question looming over the game design here which is the fact that it's a score attack game with a narrative. That question is something as follows: How do you make an 'endless score' game good in respect to player proficiency?

Let's take Pacman for example, Pacman is a deeply discussed point of consideration for how to design 'infinite score' games for many reasons. Heather and Matthewmatosis both have poured a lot of their own thoughts into it through DX by considering stuff like randomization, player proficiency, increasing difficulty, etc.

This is all in a good spirit, but the reality is this: You're most proficient player of pacman already knows the exact accurate array of moves, know exactly in what ways to manipulate the AI, and generally never feel like they are 'behind'. On top of this, Pacman miraculously ended up having an accidental end game that only absolute hardcore 'geek' players would have found. I can't say I've 'completed' arcade Pacman, probably almost nobody on this website can, but an ending does exist and thus the beauty of it being an 'endless' score game has dissipated. The difficulty of getting a 'higher' score for dedicated players is gone. A dynamic game has become flatlined with spreadsheets and planning over the years. This is the ideal case to. Compare this pure arcade game with something like Donkey Kong or Galaga to see followup problems. It's fairly clear from the outset what the methodology was for getting a higher score and so thus the motivation of play splits into 2 camps: Players who want to satisfy the urge to execute, and players that simply don't care. For the former it just ends up being an endurance test anyway and not much else. How good is your bladder to hold out to get a high score in a game you can't pause because that's the only thing stopping a highly proficient player to top the leaderboard in most games.

This problem with score becomes intensified immediately with home console gaming in a few different ways. For one, unlike arcade cabinets very few people are centralized and enthusiastic strangers to give enough of a shit about your new high score in Ninja Gaiden on the NES, like ok son thats great have you filed your W-2s yet? You might invite your friend over, but why would they care if they never played it before? The followup problem is that score became an afterthought in itself to 'narrative' design as well. As petty it may seem to bring it up, getting an infinite score in Kirby Adventure is insanely easy, it becomes a simple endurance test of walking to an enemy 10 feet forward, beating it up, walking backwards to cause it to spawn again and doing it ad infinitum until you're either bored or the score is maxxed. Far be that from the only game with that problem, almost every Megaman game has it too. Nobody considered it because it didn't matter, you would only put in the quarter for an arcade game under the motivation to either get further to see more of it or to get the high score. Now that the latter motivation is made defunct, the primary motivators become narrative or experiential. The artificial motivator to do it all better only exists in the minds of the player, to such an extent that it becomes brilliantly exaggerated to stuff like speedruns and no hit challenges, things that for the most part are best left up to the players to derive and find. But what about score as a motivator? What about game proficiency in itself? Without a well thought out score modifier it becomes a rather hollow and insulting piece of player motivation. One that we don't ever feel because it's lost. Our desire to care in a world that constantly churns from one game to the next makes it hard to find the appeal in it again, besides I don't need to be proficient if I can just watch what somebody else's efficiency at the game looks like. I don't need to play a soul level 1 run of dark souls I have too many games to play as it is and I can just watch Lobos Jr. do it and about 100 other things in the game more entertainingly and communally than than I did. Unfortunately, you fucked up too many times score, you have to be the least considered factor now (imprisoned). This is exactly the sort of issues that create games like Neon White, a game where score (time speed) is universally agreed to be its best asset is still its least capitalized on in comparison to its obsession with dating game narratives design and needless lore explanations, and then when you try to consider it in comparison to something like Lovely Planet (which often gets brought up in relate) the issue for that game though is the leaderboards are not global, theres time as a score in that game but its mostly for you and doesn't really 'do' much to motivate play that completing levels doesn't already provide. On a wider level I feel personally like the problem with this is that then both the designer and the player are completely out of touch with one another. Like, far be it from me to proselytize, but even though I like most games the only time I tend to feel like me and the score design are in harmony is when I'm playing absolutely silly shit like a golf game like Kirby's Dream Course or something lmao. So like, its only a score through and inverse minimization of score or time, rather than an accumulation of either in the other direction. Even when the motivator of score exists, it's only in its own minimization!

Enter then a game like, Quantum Bummer Blues, which exists within that score abandonment crisis and tries to intervene in some critical ways. The primary one is through health. Score is quite literally vital to beating the game in a way few games actually are, you have to get a threshold of score to refill your characters blood and life, if you don't give attention to it, you're not going to get very far at all. You have to care about getting a score in order to continue the narrative of the game. You can't just 'beat the game on 1 life' by evading everything it's not quite like that.

Following this, there's a deceptively high skill ceiling in the game if you work for it, it's just interesting because that skill ceiling is found mechanically through a very methodical patience with the game. You will fail and fail again, learn a sliver of gameplay information, and then repeat those sections again, different this time, with feeling. I don't want to give it all away but learning tricks for better play help you get just that little bit further. My main advice is read the how to very carefully and then after a few runs, read it again.

Next is the character feel. Early on you're going to be wrestling with the controls because the designer intentionally made the blood flow interstitial sections annoying to navigate. It's not just moving between straight lined pipes, you have to often trudge and crevice around these pixeled steps in the way. Which work to block and slow you down, the whole game is telling you straight from the get go 'slow the fuck down' and this design is reinforced by the fact you can at any time step into the pipes again to freeze the scene safely and just think about the plan of attack. In this process you'll realize that it's only those blue antagonist vertical shots that demand any sense of urgency and that going too fast and losing all your blood is what's going to kill you. Similarly the gravity feels like sludge. You fall incredibly fast and then have to push slowly upward, its like trying to control an sentient oil mine that threatens to end your run if you don't think things through.

Finally is how random it is, the green pellets and your specific situation going into each of the rooms can be accounted for in advance. Those green pellets start in the same place but start bouncing off in random directions very quickly. Meaning trying to section off 3 of them is going to be sporadic and random.

That's why it feels great when you finally piece all the mechanics together and pull off a successful run. You're fighting against the discomfort of your player character to essentially 'farm' points. But the more points you farm the higher your IV bag gets, and thus the faster the turrets spawn. You can very easily reach a situation where you're actually suffering from success and have to leave an area early. Creating these odd situations where getting rid of blood by painting half the screen as fast as and then hiding inside the red is the best move. This isn't even a mechanical spoiler because it's such a bizarre experience you won't even really be able to conceptualize how unintuitive it is until you actually see it in action. It's just a weird moment of balancing the various moving parts. It's the constant trade off of risk and reward and how awkward it all works is to great effect as a narrative device. It often switches between being slow and requiring a reasonable amount of risky movement and shooting. The pressure between moments of downtime to moments of blood bag balancing is incredible and shows that Heather has learned a lot from her thoughts on game design since she experimented with these same score based issues in her previous non narrative endless score game Endless Overdrive. The better you are doing in that game the most hostile it gets. My favorite side effect of this is that you can literally just enter and leave some rooms you don't like very quickly with no interactions at high levels of play with a full IV.

Yet ironically, hidden in this chaotic story about carceral torture is a genuine game where getting a higher score and playing it again not just feels fun but actually cathartic. The gameplay is spontaneous, methodical and has a lot of room for error but feeling satisfaction does not in itself come from getting to 1 million on the score counter. It comes from the wild proficiency and proof of ability to get there. The ability to know how to balance each of the moving parts.

One thing I had trouble bringing up and often do, is how score and game feel actually pervade and change the experience of a work because trying to do so in write ups like this borders on geometrical. As a result I often neglect to try, but that process of neglect is because of a historical and material neglect of the same. I don't have the tools for those kinds of explanations because I haven't had the access or time to hit up those books, but it creates an insecurity there. I can explain the textual ableism or depression of a visual novel just fine but descriptions of game design in itself are far more mysterious and ambiguous. In that sense the games 'ambiguity' around its design demands a special attention to it that you don't see much elsewhere.

The score itself doesn't really matter so much as hearing the squishy noises of a job well done and there's one important reason for that: The score doesn't show on the game over screen and no high score is actually accounted for outside of play. The only way you can commemorate the moment is by taking a screenshot or recording the game. The game makes the historical abandonment of score a genuine piece of its text. Sure whatever the game is about prison violence and the abuse of the young, its about queerphobia and all this stuff. Awesome, me and Heather get along for a reason there. But more importantly to me it's a manifesto about the narrative importance of those little points and what they can and should bring to gamefeel and for me, that's a much appreciated intervention I wasn't really considering. It's made this little few hour long gem almost certainly one of the best games of the year.

This is going to sound extremely panegyric to my friend but this is absolutely brilliant shit, I wouldn't expect anything less from an erudite woman who went to college for game design but it still highlights her far above just a friend or somebody we are all shaking the hand of out of some kind of academic respect. She genuinely is in a league of her own, bringing a much needed catharsis to game design, and for that I can only give a curtsey and a textvomit along with.

Est. Reading length: Inchoately N/A

Policy

-----------------------------------------------------------

I should note I got a free copy of the game from the developer because we are cautious friends. Not only for the sake of 'journalistic integrity' but also to point out that there's never been a situation where I played a game a developer gave me for free who I know personally and then I didn't like the game which is to say, I don't have a litmus test for how easy or hard I am to pay off. Who can say if I would have spoken about this game if I didn't like it? That being said the primary reason it is this way is out of poverty and not because I don't think the game is worth the money or anything like that. I definitely think with the amount of time it'll take to figure it out its totally worth it and one of the best games of the year so far.

Anyway, in respect to what everyone else has already offered on the game, I'll skip all the theming and presentation talk and just talk about the game mechanics proper. To me I feel like there's one hanging rhetorical question looming over the game design here which is the fact that it's a score attack game with a narrative. That question is something as follows: How do you make an 'endless score' game good in respect to player proficiency?

Let's take Pacman for example, Pacman is a deeply discussed point of consideration for how to design 'infinite score' games for many reasons. Heather and Matthewmatosis both have poured a lot of their own thoughts into it through DX by considering stuff like randomization, player proficiency, increasing difficulty, etc.

This is all in a good spirit, but the reality is this: You're most proficient player of pacman already knows the exact accurate array of moves, know exactly in what ways to manipulate the AI, and generally never feel like they are 'behind'. On top of this, Pacman miraculously ended up having an accidental end game that only absolute hardcore 'geek' players would have found. I can't say I've 'completed' arcade Pacman, probably almost nobody on this website can, but an ending does exist and thus the beauty of it being an 'endless' score game has dissipated. The difficulty of getting a 'higher' score for dedicated players is gone. A dynamic game has become flatlined with spreadsheets and planning over the years. This is the ideal case to. Compare this pure arcade game with something like Donkey Kong or Galaga to see followup problems. It's fairly clear from the outset what the methodology was for getting a higher score and so thus the motivation of play splits into 2 camps: Players who want to satisfy the urge to execute, and players that simply don't care. For the former it just ends up being an endurance test anyway and not much else. How good is your bladder to hold out to get a high score in a game you can't pause because that's the only thing stopping a highly proficient player to top the leaderboard in most games.

This problem with score becomes intensified immediately with home console gaming in a few different ways. For one, unlike arcade cabinets very few people are centralized and enthusiastic strangers to give enough of a shit about your new high score in Ninja Gaiden on the NES, like ok son thats great have you filed your W-2s yet? You might invite your friend over, but why would they care if they never played it before? The followup problem is that score became an afterthought in itself to 'narrative' design as well. As petty it may seem to bring it up, getting an infinite score in Kirby Adventure is insanely easy, it becomes a simple endurance test of walking to an enemy 10 feet forward, beating it up, walking backwards to cause it to spawn again and doing it ad infinitum until you're either bored or the score is maxxed. Far be that from the only game with that problem, almost every Megaman game has it too. Nobody considered it because it didn't matter, you would only put in the quarter for an arcade game under the motivation to either get further to see more of it or to get the high score. Now that the latter motivation is made defunct, the primary motivators become narrative or experiential. The artificial motivator to do it all better only exists in the minds of the player, to such an extent that it becomes brilliantly exaggerated to stuff like speedruns and no hit challenges, things that for the most part are best left up to the players to derive and find. But what about score as a motivator? What about game proficiency in itself? Without a well thought out score modifier it becomes a rather hollow and insulting piece of player motivation. One that we don't ever feel because it's lost. Our desire to care in a world that constantly churns from one game to the next makes it hard to find the appeal in it again, besides I don't need to be proficient if I can just watch what somebody else's efficiency at the game looks like. I don't need to play a soul level 1 run of dark souls I have too many games to play as it is and I can just watch Lobos Jr. do it and about 100 other things in the game more entertainingly and communally than than I did. Unfortunately, you fucked up too many times score, you have to be the least considered factor now (imprisoned). This is exactly the sort of issues that create games like Neon White, a game where score (time speed) is universally agreed to be its best asset is still its least capitalized on in comparison to its obsession with dating game narratives design and needless lore explanations, and then when you try to consider it in comparison to something like Lovely Planet (which often gets brought up in relate) the issue for that game though is the leaderboards are not global, theres time as a score in that game but its mostly for you and doesn't really 'do' much to motivate play that completing levels doesn't already provide. On a wider level I feel personally like the problem with this is that then both the designer and the player are completely out of touch with one another. Like, far be it from me to proselytize, but even though I like most games the only time I tend to feel like me and the score design are in harmony is when I'm playing absolutely silly shit like a golf game like Kirby's Dream Course or something lmao. So like, its only a score through and inverse minimization of score or time, rather than an accumulation of either in the other direction. Even when the motivator of score exists, it's only in its own minimization!

Enter then a game like, Quantum Bummer Blues, which exists within that score abandonment crisis and tries to intervene in some critical ways. The primary one is through health. Score is quite literally vital to beating the game in a way few games actually are, you have to get a threshold of score to refill your characters blood and life, if you don't give attention to it, you're not going to get very far at all. You have to care about getting a score in order to continue the narrative of the game. You can't just 'beat the game on 1 life' by evading everything it's not quite like that.

Following this, there's a deceptively high skill ceiling in the game if you work for it, it's just interesting because that skill ceiling is found mechanically through a very methodical patience with the game. You will fail and fail again, learn a sliver of gameplay information, and then repeat those sections again, different this time, with feeling. I don't want to give it all away but learning tricks for better play help you get just that little bit further. My main advice is read the how to very carefully and then after a few runs, read it again.

Next is the character feel. Early on you're going to be wrestling with the controls because the designer intentionally made the blood flow interstitial sections annoying to navigate. It's not just moving between straight lined pipes, you have to often trudge and crevice around these pixeled steps in the way. Which work to block and slow you down, the whole game is telling you straight from the get go 'slow the fuck down' and this design is reinforced by the fact you can at any time step into the pipes again to freeze the scene safely and just think about the plan of attack. In this process you'll realize that it's only those blue antagonist vertical shots that demand any sense of urgency and that going too fast and losing all your blood is what's going to kill you. Similarly the gravity feels like sludge. You fall incredibly fast and then have to push slowly upward, its like trying to control an sentient oil mine that threatens to end your run if you don't think things through.

Finally is how random it is, the green pellets and your specific situation going into each of the rooms can be accounted for in advance. Those green pellets start in the same place but start bouncing off in random directions very quickly. Meaning trying to section off 3 of them is going to be sporadic and random.

That's why it feels great when you finally piece all the mechanics together and pull off a successful run. You're fighting against the discomfort of your player character to essentially 'farm' points. But the more points you farm the higher your IV bag gets, and thus the faster the turrets spawn. You can very easily reach a situation where you're actually suffering from success and have to leave an area early. Creating these odd situations where getting rid of blood by painting half the screen as fast as and then hiding inside the red is the best move. This isn't even a mechanical spoiler because it's such a bizarre experience you won't even really be able to conceptualize how unintuitive it is until you actually see it in action. It's just a weird moment of balancing the various moving parts. It's the constant trade off of risk and reward and how awkward it all works is to great effect as a narrative device. It often switches between being slow and requiring a reasonable amount of risky movement and shooting. The pressure between moments of downtime to moments of blood bag balancing is incredible and shows that Heather has learned a lot from her thoughts on game design since she experimented with these same score based issues in her previous non narrative endless score game Endless Overdrive. The better you are doing in that game the most hostile it gets. My favorite side effect of this is that you can literally just enter and leave some rooms you don't like very quickly with no interactions at high levels of play with a full IV.

Yet ironically, hidden in this chaotic story about carceral torture is a genuine game where getting a higher score and playing it again not just feels fun but actually cathartic. The gameplay is spontaneous, methodical and has a lot of room for error but feeling satisfaction does not in itself come from getting to 1 million on the score counter. It comes from the wild proficiency and proof of ability to get there. The ability to know how to balance each of the moving parts.

One thing I had trouble bringing up and often do, is how score and game feel actually pervade and change the experience of a work because trying to do so in write ups like this borders on geometrical. As a result I often neglect to try, but that process of neglect is because of a historical and material neglect of the same. I don't have the tools for those kinds of explanations because I haven't had the access or time to hit up those books, but it creates an insecurity there. I can explain the textual ableism or depression of a visual novel just fine but descriptions of game design in itself are far more mysterious and ambiguous. In that sense the games 'ambiguity' around its design demands a special attention to it that you don't see much elsewhere.

The score itself doesn't really matter so much as hearing the squishy noises of a job well done and there's one important reason for that: The score doesn't show on the game over screen and no high score is actually accounted for outside of play. The only way you can commemorate the moment is by taking a screenshot or recording the game. The game makes the historical abandonment of score a genuine piece of its text. Sure whatever the game is about prison violence and the abuse of the young, its about queerphobia and all this stuff. Awesome, me and Heather get along for a reason there. But more importantly to me it's a manifesto about the narrative importance of those little points and what they can and should bring to gamefeel and for me, that's a much appreciated intervention I wasn't really considering. It's made this little few hour long gem almost certainly one of the best games of the year.

This is going to sound extremely panegyric to my friend but this is absolutely brilliant shit, I wouldn't expect anything less from an erudite woman who went to college for game design but it still highlights her far above just a friend or somebody we are all shaking the hand of out of some kind of academic respect. She genuinely is in a league of her own, bringing a much needed catharsis to game design, and for that I can only give a curtsey and a textvomit along with.

I have not played libble rabble as seems to be the comparison of choice for this game, but I have played qix quite a bit, and like both of these qbb is a space-manipulation game that encourages the player to strategically navigate around objects with a stochastic movement pattern. in qbb's case your goal is to herd bouncing atoms into areas to be quartered off by your blood trail, leaving them to ricochet continuously while corroding your trail in the process for points. the atoms can also combine by colliding, yielding larger atoms that both chew through your trail more quickly as well as yielding extra points when picked up by the player.

surrounding this is a trifecta of resources each vying for your attention as you move from area to area. your blood supply is generally the most pressing of the three; the more you move, the more it dwindles, and losing it all means instant death. this forces some level of movement rationing in order to avoid overspending your supply, and encourages the player to constantly seek out scoring opportunities, as each 5000 points gained replinshes your stock. while grabbing atoms for quick points can pay dividends in the short term, it also raises a counter on top of your blood supply that signifies how much blood you lose with your movement. the only way to decrease this is by sacrificing a life - your third stat - via taking damage from a turret. these are somewhat rare as they only are awarded every 10000 points, making casual play a survival task where the player is constantly trying to eke out another 10000 points to ease their blood loss as they progress.

for those willing to jettison their blood supply more quickly, a bloodshot can be taken that creates trail for you and can hit an atom to increase its velocity and damage. this move is the crux of high-level play, and when used well allows for swift pincer maneuvers around atoms nearby or a quick way to speed up atoms and get points churning. to end the bloodshot's movement pattern, you must catch it, expending more blood in the process. catching the bloodshot is difficult and takes a lot of practice and aiming consideration in order to use effectively. I will comment that firing is a fiddly task to learn given the specific chain of steps that must be followed - press down then aim then release down without releasing your aim direction - and I specifically had trouble until I realized that the aiming direction and down button couldn't be released simultaneously.

these aforementioned turrets appear at your location on a timer inversely proportional to your blood supply, thus both serving as dynamic difficulty for those with ample blood while also keeping the player moving. in theory this works well to prevent stalling tactics, but a side-effect of the bloodshot makes them somewhat moot. the player is subject to a gravity effect that both keeps them falling as well as hampering their vertical movement; however, this effect is nullified when aiming the bloodshot. thus, the player can freely stall by aiming without firing all while strategically moving vertically to place columns of turrets out of range, which lets the atoms cook up points without harm to the player. I felt pressured to resort to this when the bloodshot was too risky, and it slowed down the pace of the game too much for my liking once turrets became moot hazards.

this is exacerbated somewhat by the level design, which draw from a variety of imagery related to the text overlayed on each area. it is my perception that this was an intentional choice given goufygoggs's previous video on bangai-o. I definitely agree that this is a liberating choice especially to amplify the overarching story, but I do feel obligated to note that sometimes the areas damage play with certain odd structures. any area with a tight corridor branching off of the main "room" of the level will tend to get atoms stuck in inside given that their trajectory on a bounce is randomized, which can make them virtually inaccessible outside of wasting blood to grab them outright. it also makes the bloodshot difficult to justify using in certain levels, which seems to have been considered given that the later stages reopen the playing field and avoid the claustrophobia of midgame.

I have a few QoL things I would like to mention as well:

-I can live without a keyboard rebind option but a control display on the main menu is conspicuously missing. this wouldn't be an issue except the down arrow key is actually the confirm button, and thus those (like me) attempting to scroll down to the "how to play" section initially will end up starting the game instead

-a option to restart the run or return to main menu on the pause menu would go a long way towards making doomed runs less annoying

-the character square flashes but it is low-grade and can be very hard to make out as the screen gets more complicated. perhaps a different color or brighter flash would be useful

-the constant ridges cause the player to get stuck frequently in the interstitual sections, which is more of an annoyance than anything and also prevented me from paying attention to the text unless I stopped in place. otherwise I think the interstitual sections are a smart way to gate progression and ensure the player is managing their blood supply/drain rate adequately

-evidently the diagonal movement is meant to be the fastest vertical movement option given the gravity mechanic, but it feels jerky and unintuitive when moving from or to the normal purely-vertical velocity. I'm not sure the gravity is necessary at all given that stalling is still present as a mechanic

admittedly I didn't quite paint the entire final room red, but I still felt very satisfied to finally overcome the challenge of slowly learning the game mechanics and determining how to assess each situation quickly. the resource web is tightly interwoven and smartly designed to ensure that you are never truly safe no matter what tactics you choose. in a way, this made it resemble an arcade-tinted survival horror game given the level of resource stress I went under the more I played. worth buying for fans of intentionally-designed and hard-to-master arcade titles.

surrounding this is a trifecta of resources each vying for your attention as you move from area to area. your blood supply is generally the most pressing of the three; the more you move, the more it dwindles, and losing it all means instant death. this forces some level of movement rationing in order to avoid overspending your supply, and encourages the player to constantly seek out scoring opportunities, as each 5000 points gained replinshes your stock. while grabbing atoms for quick points can pay dividends in the short term, it also raises a counter on top of your blood supply that signifies how much blood you lose with your movement. the only way to decrease this is by sacrificing a life - your third stat - via taking damage from a turret. these are somewhat rare as they only are awarded every 10000 points, making casual play a survival task where the player is constantly trying to eke out another 10000 points to ease their blood loss as they progress.

for those willing to jettison their blood supply more quickly, a bloodshot can be taken that creates trail for you and can hit an atom to increase its velocity and damage. this move is the crux of high-level play, and when used well allows for swift pincer maneuvers around atoms nearby or a quick way to speed up atoms and get points churning. to end the bloodshot's movement pattern, you must catch it, expending more blood in the process. catching the bloodshot is difficult and takes a lot of practice and aiming consideration in order to use effectively. I will comment that firing is a fiddly task to learn given the specific chain of steps that must be followed - press down then aim then release down without releasing your aim direction - and I specifically had trouble until I realized that the aiming direction and down button couldn't be released simultaneously.

these aforementioned turrets appear at your location on a timer inversely proportional to your blood supply, thus both serving as dynamic difficulty for those with ample blood while also keeping the player moving. in theory this works well to prevent stalling tactics, but a side-effect of the bloodshot makes them somewhat moot. the player is subject to a gravity effect that both keeps them falling as well as hampering their vertical movement; however, this effect is nullified when aiming the bloodshot. thus, the player can freely stall by aiming without firing all while strategically moving vertically to place columns of turrets out of range, which lets the atoms cook up points without harm to the player. I felt pressured to resort to this when the bloodshot was too risky, and it slowed down the pace of the game too much for my liking once turrets became moot hazards.

this is exacerbated somewhat by the level design, which draw from a variety of imagery related to the text overlayed on each area. it is my perception that this was an intentional choice given goufygoggs's previous video on bangai-o. I definitely agree that this is a liberating choice especially to amplify the overarching story, but I do feel obligated to note that sometimes the areas damage play with certain odd structures. any area with a tight corridor branching off of the main "room" of the level will tend to get atoms stuck in inside given that their trajectory on a bounce is randomized, which can make them virtually inaccessible outside of wasting blood to grab them outright. it also makes the bloodshot difficult to justify using in certain levels, which seems to have been considered given that the later stages reopen the playing field and avoid the claustrophobia of midgame.

I have a few QoL things I would like to mention as well:

-I can live without a keyboard rebind option but a control display on the main menu is conspicuously missing. this wouldn't be an issue except the down arrow key is actually the confirm button, and thus those (like me) attempting to scroll down to the "how to play" section initially will end up starting the game instead

-a option to restart the run or return to main menu on the pause menu would go a long way towards making doomed runs less annoying

-the character square flashes but it is low-grade and can be very hard to make out as the screen gets more complicated. perhaps a different color or brighter flash would be useful

-the constant ridges cause the player to get stuck frequently in the interstitual sections, which is more of an annoyance than anything and also prevented me from paying attention to the text unless I stopped in place. otherwise I think the interstitual sections are a smart way to gate progression and ensure the player is managing their blood supply/drain rate adequately

-evidently the diagonal movement is meant to be the fastest vertical movement option given the gravity mechanic, but it feels jerky and unintuitive when moving from or to the normal purely-vertical velocity. I'm not sure the gravity is necessary at all given that stalling is still present as a mechanic

admittedly I didn't quite paint the entire final room red, but I still felt very satisfied to finally overcome the challenge of slowly learning the game mechanics and determining how to assess each situation quickly. the resource web is tightly interwoven and smartly designed to ensure that you are never truly safe no matter what tactics you choose. in a way, this made it resemble an arcade-tinted survival horror game given the level of resource stress I went under the more I played. worth buying for fans of intentionally-designed and hard-to-master arcade titles.

"When you're pushed, killing's as easy as breathing."

Video games are violent.

Shocker, I know. Stunned silence across the board, I'm sure. The conversation around violence in games is one that is as old as the medium itself, and is maybe the most misguided and exhausting of the conversations around the medium, in the mainstream at least. Largely, I think this is because the counter-response to the, indeed, worthy-of-critique ubiquity of games were you hurt and kill others, is so routinely embarrassing.

If you google "non-violent video games", one of the first games that crops up is Cities: Skylines. While it is true that you do not personally murder anyone with a sword in Cities: Skylines, and setting aside the fact that you can use disasters to commit absolute genocide of your largely invisible population, to describe Cities: Skylines as a non-violent game is mind-bogglingly ridiculous to me. The ideology that drives this game - indeed, one that drives the entire genre - is that of growth - growth upon growth, nothing but growth in this blasted land, the incarnation of Reaganomics, the management of the human mind through the construction of the space around them to ensure efficiency.

Sure, Cities: Skylines is slightly less toxic than it's overbearing predecessor SimCity, the breakout title from Will Wright, who's game development portfolio consists almost entirely of adaptations of neo-conservative texts he consumed completely uncritically. It has a huge emphasis on public transport, and the gameplay loop of that title is defined by your attempt to stem the tide of traffic clogging the arteries of your city with the kind of Smart, Walkable, Mixed-Use Urbanism that is Illegal To Build In Most American Cities...as long as it still fits within the image of the American megalopolis super-city. Everything about Cities: Skylines pushes you to grow, small cosy towns at one with nature are not considered a valid end goal but an implicit failure to follow the path of perpetual growth, of endless explosive population and income increase, to make a city of towering skyscrapers, booming industry, bustling streets, to the point that the game will constrain your creative powers until you meet certain thresholds of population and size.

One need only look at London, New York, Los Angeles, Dublin, hell, even my own home city of Belfast, tiny as it is in comparison to these others, to see the consequences of this ideology. Their impact on the world ecologically, their impact on how we live our lives, their impact on our mental state...this is all violence, real violence, but violence that is abstracted, violence where you can't see the knife and the throat it cuts into, until you really look, until you see all those curved benches around town that hurt to lie on, that no longer have backrests or are dotted with little "armrests" for what they really are.

By any reasonable metric that understands how the world works and how systems and laws can cause harm to others, Cities: Skylines is a violent video game. Even a player that is conscious of the environment, that takes the time to produce robust public transport solutions, you're almost certainly going to commit more violence to the little abstract people of Spunkburg or whatever than Solid Snake could manage over the course of his mission to Shadow Moses. But it doesn't feel that way, because the violence is abstracted, hidden behind spreadsheets and charts and corporate focus-tested interface design, all rounded edges and pastel colors. The violence is abstract, over there.

Now, I'm far from the first person to say this, and there is plenty of conversation about violent video games that takes an actual understanding of what material violence actually is into account. But most of that conversation is relegated to either actual academic spaces or occasionally, in alternative academic works on YouTube or, indeed, Backloggd. Rarely does it percolate into the mainstream discourse enough to change the conception of what a violent video game actually is. The kind of mainstream critique of violent video games - one that can be seen most strongly in the Wholesome Games movement - does not seem to me an actual objection to Violence, but a discomfort with it's presentation, with the fact that the violence of tearing open an Imp's head in Doom Eternal is impossible to ignore as anything other than the violent act that it is. It is not an actual concern about the depiction or normalization of violence in video games, it is principally, an objection to the viscera of it's presentation. It is, if you will pardon my French, a bourgeois indulgence.

I don't think it's impossible to make truly non-violent video games, nor do I think that the ubiquity of games where the primary/sole modes of interaction it facilitates is killing is unworthy of critique. But I do think that the nature of what violence actually is makes that far more difficult than one might initially think.

Let me explain by talking about something that I think Backloggd would do well to consider more often: Board Games. If one was so inclined, one could categorize most any board game into one of two camps: abstract games, and thematic games. A thematic board game is one that would use an aesthetic, narrative, or other kind of theming in order to place the mechanics of the game into a context in order to facilitate the intentions of the game. For example, Monopoly is a game where each player plays the role of a real-estate/business mogul who is travelling around London/New York/The Fortnite Island buying up properties in order to eventually win the game by being the player with the most money at the end. As a game where the explicit goal is to bankrupt every other player, Monopoly is plainly a Violent Board Game, even if at no point does your little top hat take out a gun and shoot the thimble in the head. But what about Abstract games? Chess is probably the most famous abstract game in the world, it's mechanics and rules are offered no real justification or contextualization by a theme - castles, in real life, contrary to Chess' bizarre worldview, can actually move diagonally. And yet, despite this, the violence of the real world creeps into Chess. It's pieces are named according to the hierarchy of the feudal system, with higher pieces being ever more powerful and capable, up to the King, who is functionally invincible in a way the other pieces aren't.

What about Go? This Chinese abstract game that is at least 2500 years old, predating most of the concepts that have been mentioned in this review, doesn't even have named spaces or concepts - players simply take turns placing colored pieces and whoever has the most points at the end wins. But even though Go doesn't have anything resembling a traditional theme, it remains a game of violence - most obviously through the way an opponents pieces can be captured, but also through how scores are tallied, through how big the territory you control is. Even though there are no soldiers, even though there is none of the formal mechanisms of violence, conversations about Go refer to it's movements and situations as battles in a war because the mechanics are derived from violent social constructions about the capture and ownership of territory and individuals.

The dichotomy between theme and abstract is not as present in video games, but there does remain a sliding scale between games that attempt some form of verisimilitude in it's visuals and play, and those that preference kinesthetic interaction far more than caring to contextualize that. Which brings me, at last, to Libble Rabble.

Libble Rabble is the game that I thought about the most while playing Quantum Bummer Blues. This arcade classic from the designer of Pac-Man is far from the traditional image of "violent video game" that that phrase conjures. It is a (mostly) abstract game where the player controls two cursors at once, drawling lines around pegs in the game space to capture space inside them. There is no real context for who the player is or why they are doing this, and yet, much like Chess or Go, the violence of our society is inherent in these mechanics. Encircling land on the map changes it's hue, marking your territory like an explorer planting a flag of plain colors, and if you happen to capture objects or creatures in that territory, they vanish, and in their place, offer points. The encirclement and capture of living creatures is core to the loop of Libble Rabble.

I don't say this to condemn Libble Rabble - I have no actual ethical concerns about it whatsoever - nor to make a statement along the lines of "Pac-Man is actually a guy taking a load of drugs at a rave". Instead, I hope all of this has convincingly demonstrated that violence, as a concept, exists on so many levels beyond the act of hurting virtual dolls (incidentally, please read Vehmently's incredible piece on that particular aesthetic subject ) and that "non-violent games" are instead merely games that successfully abstract out their violence so that we can be comforted by the illusion of it's non-presence, and that the fetishization of that illusion leads us to uncomfortable places.

Violence is not inescapable in play, but games are violent, and they are violent because we are violent, because they are made, produced, and played by a culture where violence is ubiquitous. Not because human beings are a kind of hobbesian construct of pure violence and that Link slashing a bokoblin in some way taps into a fundamental human instinct towards harming others, but because we live in a violent and flammable world that snaps and twists and folds our limbs into origami shapes that fold our mind into thoughts and places where violence is normal. We probably aren't going to juggle-combo an opponent in the King of Iron First Tournament in our everyday lives, but violence is all around us, it is inherent to the structures and systems that entomb us, it's only hidden from view, abstracted and blurred by those same systems, and it is only when the abstraction is removed and the image is in focus do we acknowledge it for what it is.

It is this that is so remarkable about Quantum Bummer Blues. In play, it bears remarkable similarity to abstract games, and Libble Rabble in particular, feels to me like a clear ancestor of this game's design. But unlike all these other games, QBB marks it's body deep with the violence of our world, never allowing anything you do to be comfortably abstracted. Any potential implication of the premise of it's play is fully incorporated - what could be a simple contextless line is a trail of blood leaning away from a murdered corpse, and each action is contextualized by the game's compelling stream-of-consciousness writing. Self-harm is a mechanic in this game, a delicate balance that was the only way I got as far as I did, and the game faces this head-on. And the abstract maze that you bleed through is a prison tucked far out of earth's sight, where human minds and bodies are bent and broken and twisted into shapes that are comforting to our bourgeois bounds of acceptability and comfort. More than a game that deconstructs assumptions of video game mechanics, more than one that exposes a dark truth about the world narratively, QBB, by violently jamming traditionally abstract arcade-style mechanics into an aesthetic and narrative framework that absolutely refuses to fade into the background and let itself be blurred out, articulates with astonishing clarity just how violent our society and the things it creates is.

In a space that so often dodges the full implications of it's mechanics, where the more serious the themes, the more abstractions are removed, Quantum Bummer Blues is a blast of summer wind, a game that is brutally, angrily honest, about itself, about games, and how these things fit into a burning world. An act not of condemnation, but excoriation.

This is the world. How do you stand it?

It's as easy as breathing.

Video games are violent.

Shocker, I know. Stunned silence across the board, I'm sure. The conversation around violence in games is one that is as old as the medium itself, and is maybe the most misguided and exhausting of the conversations around the medium, in the mainstream at least. Largely, I think this is because the counter-response to the, indeed, worthy-of-critique ubiquity of games were you hurt and kill others, is so routinely embarrassing.

If you google "non-violent video games", one of the first games that crops up is Cities: Skylines. While it is true that you do not personally murder anyone with a sword in Cities: Skylines, and setting aside the fact that you can use disasters to commit absolute genocide of your largely invisible population, to describe Cities: Skylines as a non-violent game is mind-bogglingly ridiculous to me. The ideology that drives this game - indeed, one that drives the entire genre - is that of growth - growth upon growth, nothing but growth in this blasted land, the incarnation of Reaganomics, the management of the human mind through the construction of the space around them to ensure efficiency.

Sure, Cities: Skylines is slightly less toxic than it's overbearing predecessor SimCity, the breakout title from Will Wright, who's game development portfolio consists almost entirely of adaptations of neo-conservative texts he consumed completely uncritically. It has a huge emphasis on public transport, and the gameplay loop of that title is defined by your attempt to stem the tide of traffic clogging the arteries of your city with the kind of Smart, Walkable, Mixed-Use Urbanism that is Illegal To Build In Most American Cities...as long as it still fits within the image of the American megalopolis super-city. Everything about Cities: Skylines pushes you to grow, small cosy towns at one with nature are not considered a valid end goal but an implicit failure to follow the path of perpetual growth, of endless explosive population and income increase, to make a city of towering skyscrapers, booming industry, bustling streets, to the point that the game will constrain your creative powers until you meet certain thresholds of population and size.

One need only look at London, New York, Los Angeles, Dublin, hell, even my own home city of Belfast, tiny as it is in comparison to these others, to see the consequences of this ideology. Their impact on the world ecologically, their impact on how we live our lives, their impact on our mental state...this is all violence, real violence, but violence that is abstracted, violence where you can't see the knife and the throat it cuts into, until you really look, until you see all those curved benches around town that hurt to lie on, that no longer have backrests or are dotted with little "armrests" for what they really are.

By any reasonable metric that understands how the world works and how systems and laws can cause harm to others, Cities: Skylines is a violent video game. Even a player that is conscious of the environment, that takes the time to produce robust public transport solutions, you're almost certainly going to commit more violence to the little abstract people of Spunkburg or whatever than Solid Snake could manage over the course of his mission to Shadow Moses. But it doesn't feel that way, because the violence is abstracted, hidden behind spreadsheets and charts and corporate focus-tested interface design, all rounded edges and pastel colors. The violence is abstract, over there.

Now, I'm far from the first person to say this, and there is plenty of conversation about violent video games that takes an actual understanding of what material violence actually is into account. But most of that conversation is relegated to either actual academic spaces or occasionally, in alternative academic works on YouTube or, indeed, Backloggd. Rarely does it percolate into the mainstream discourse enough to change the conception of what a violent video game actually is. The kind of mainstream critique of violent video games - one that can be seen most strongly in the Wholesome Games movement - does not seem to me an actual objection to Violence, but a discomfort with it's presentation, with the fact that the violence of tearing open an Imp's head in Doom Eternal is impossible to ignore as anything other than the violent act that it is. It is not an actual concern about the depiction or normalization of violence in video games, it is principally, an objection to the viscera of it's presentation. It is, if you will pardon my French, a bourgeois indulgence.

I don't think it's impossible to make truly non-violent video games, nor do I think that the ubiquity of games where the primary/sole modes of interaction it facilitates is killing is unworthy of critique. But I do think that the nature of what violence actually is makes that far more difficult than one might initially think.

Let me explain by talking about something that I think Backloggd would do well to consider more often: Board Games. If one was so inclined, one could categorize most any board game into one of two camps: abstract games, and thematic games. A thematic board game is one that would use an aesthetic, narrative, or other kind of theming in order to place the mechanics of the game into a context in order to facilitate the intentions of the game. For example, Monopoly is a game where each player plays the role of a real-estate/business mogul who is travelling around London/New York/The Fortnite Island buying up properties in order to eventually win the game by being the player with the most money at the end. As a game where the explicit goal is to bankrupt every other player, Monopoly is plainly a Violent Board Game, even if at no point does your little top hat take out a gun and shoot the thimble in the head. But what about Abstract games? Chess is probably the most famous abstract game in the world, it's mechanics and rules are offered no real justification or contextualization by a theme - castles, in real life, contrary to Chess' bizarre worldview, can actually move diagonally. And yet, despite this, the violence of the real world creeps into Chess. It's pieces are named according to the hierarchy of the feudal system, with higher pieces being ever more powerful and capable, up to the King, who is functionally invincible in a way the other pieces aren't.

What about Go? This Chinese abstract game that is at least 2500 years old, predating most of the concepts that have been mentioned in this review, doesn't even have named spaces or concepts - players simply take turns placing colored pieces and whoever has the most points at the end wins. But even though Go doesn't have anything resembling a traditional theme, it remains a game of violence - most obviously through the way an opponents pieces can be captured, but also through how scores are tallied, through how big the territory you control is. Even though there are no soldiers, even though there is none of the formal mechanisms of violence, conversations about Go refer to it's movements and situations as battles in a war because the mechanics are derived from violent social constructions about the capture and ownership of territory and individuals.

The dichotomy between theme and abstract is not as present in video games, but there does remain a sliding scale between games that attempt some form of verisimilitude in it's visuals and play, and those that preference kinesthetic interaction far more than caring to contextualize that. Which brings me, at last, to Libble Rabble.

Libble Rabble is the game that I thought about the most while playing Quantum Bummer Blues. This arcade classic from the designer of Pac-Man is far from the traditional image of "violent video game" that that phrase conjures. It is a (mostly) abstract game where the player controls two cursors at once, drawling lines around pegs in the game space to capture space inside them. There is no real context for who the player is or why they are doing this, and yet, much like Chess or Go, the violence of our society is inherent in these mechanics. Encircling land on the map changes it's hue, marking your territory like an explorer planting a flag of plain colors, and if you happen to capture objects or creatures in that territory, they vanish, and in their place, offer points. The encirclement and capture of living creatures is core to the loop of Libble Rabble.

I don't say this to condemn Libble Rabble - I have no actual ethical concerns about it whatsoever - nor to make a statement along the lines of "Pac-Man is actually a guy taking a load of drugs at a rave". Instead, I hope all of this has convincingly demonstrated that violence, as a concept, exists on so many levels beyond the act of hurting virtual dolls (incidentally, please read Vehmently's incredible piece on that particular aesthetic subject ) and that "non-violent games" are instead merely games that successfully abstract out their violence so that we can be comforted by the illusion of it's non-presence, and that the fetishization of that illusion leads us to uncomfortable places.

Violence is not inescapable in play, but games are violent, and they are violent because we are violent, because they are made, produced, and played by a culture where violence is ubiquitous. Not because human beings are a kind of hobbesian construct of pure violence and that Link slashing a bokoblin in some way taps into a fundamental human instinct towards harming others, but because we live in a violent and flammable world that snaps and twists and folds our limbs into origami shapes that fold our mind into thoughts and places where violence is normal. We probably aren't going to juggle-combo an opponent in the King of Iron First Tournament in our everyday lives, but violence is all around us, it is inherent to the structures and systems that entomb us, it's only hidden from view, abstracted and blurred by those same systems, and it is only when the abstraction is removed and the image is in focus do we acknowledge it for what it is.

It is this that is so remarkable about Quantum Bummer Blues. In play, it bears remarkable similarity to abstract games, and Libble Rabble in particular, feels to me like a clear ancestor of this game's design. But unlike all these other games, QBB marks it's body deep with the violence of our world, never allowing anything you do to be comfortably abstracted. Any potential implication of the premise of it's play is fully incorporated - what could be a simple contextless line is a trail of blood leaning away from a murdered corpse, and each action is contextualized by the game's compelling stream-of-consciousness writing. Self-harm is a mechanic in this game, a delicate balance that was the only way I got as far as I did, and the game faces this head-on. And the abstract maze that you bleed through is a prison tucked far out of earth's sight, where human minds and bodies are bent and broken and twisted into shapes that are comforting to our bourgeois bounds of acceptability and comfort. More than a game that deconstructs assumptions of video game mechanics, more than one that exposes a dark truth about the world narratively, QBB, by violently jamming traditionally abstract arcade-style mechanics into an aesthetic and narrative framework that absolutely refuses to fade into the background and let itself be blurred out, articulates with astonishing clarity just how violent our society and the things it creates is.

In a space that so often dodges the full implications of it's mechanics, where the more serious the themes, the more abstractions are removed, Quantum Bummer Blues is a blast of summer wind, a game that is brutally, angrily honest, about itself, about games, and how these things fit into a burning world. An act not of condemnation, but excoriation.

This is the world. How do you stand it?

It's as easy as breathing.